Christopher C. Hull is the author of Grassroots Rules: How the Iowa Caucuses Help Elect American Presidents (Stanford University Press, 2007), as well as more than one-hundred peer-reviewed articles, book chapters, conference papers. and op-eds.

What if it’s diversity-driven hiring itself that is causing America’s decreasing ideological diversity in the academy? That is, what if the power over professor selection seized by those claiming their intent is to increase diversity in sex and race is de facto and on average used to choose Leftists instead? This study presents evidence that this may be so.

There is little question the Ivy Tower’s ideological diversity is on the decline, and more specifically that the professoriate is moving leftward.

The Leftward Lurch of U.S. Academics

Beginning about 1989, a spate of studies suggests, the percentage of American academics on the political left began increasing substantially. For instance, while about 39 percent of surveyed professors described themselves as on the left in 1984, 62 percent did so in 1999.1 As this leftward movement took place, one study noted, a “progressive” and “establishment” camp developed within the academic left.2 Similarly, in 2007, other scholars found that within a growing academic left, 17.6 percent of social scientists surveyed self-identified as “Marxist,” and those calling themselves “liberal” and “radical” rose to 24 percent.3 In 2014, these same scholars documented professors’ “leftward tilt” with two increasingly clear camps on the left.4

By contrast, the observed percentage of self-identified Democrats may have actually ticked down among all academics from 50 percent in 1999 to 46 percent in 2000.5 Regardless, by 2006 it had bobbed back up to 51 percent, and at liberal arts colleges at least it reached nearly 57 percent by 2018.6 Other scholars found no significant differences between Democratic and Republican professors on “public policies that regulate personal conduct,” meaning partisanship understated ideological uniformity.7

Among surveyed social scientists, self-identified Democrats rose from 46 percent in 1955 to 55 percent in 1999, to about 56 percent in 2006.8 By 2016, Democrat-to-Republican ratios had climbed to 11.5 to 1 among liberal arts social scientists.9 Most striking, perhaps, Democrats rose from 63 percent of psychologists in 1999 to 77 percent in 2006.10

Among surveyed political scientists, Democrats actually decreased from 58 percent in 1999 to 50 percent in 2006—yet the ratio of Democratic to Republican political scientists stood at least six to one.11 By 2018, another scholar found 8.2 registered Democratic political science faculty members for every Republican.12

Analogously, the percentage of self-identified “liberal” academics increased from 1955 through at least 2009.13 Granted, in the middle of the twentieth century, “liberal” tended to describe those who embrace fundamental ideals of freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, the separation of church and state, and the right to due process and equality under the law; more recently, “liberal” came to imply support for government intervention intended to right perceived wrongs, policies historically characterized by critics as “tax and spend.”14

Regardless, a series of studies has demonstrated that since the 1970s, American professors broadly and particularly in social sciences had become “much more politically liberal.”15 By 2011, in fact, scholars estimated about three liberal faculty members for every conservative.16 In 2014 a major survey found that 59.8 percent of college professors self-identified as liberal or far left, reaching 69.8 percent in non-sectarian institutions.17

Among political scientists and historians, 65.8 percent self-identified as “liberal” or “far left” in 1989; by 1992, that figure had crept up to 67.0 percent.18 By 2009, 79 percent of political scientists self-identified as liberal, with the percentage of conservatives down to a paltry 2 percent.19 Finally, in a 2016 study among social psychologists, out of a sample size of 326 respondents, only one had policy views even slightly right of center, 89.3 percent self-identified as “liberal” or “very liberal,” and fully 96 percent were clustered left-of-center.20

One study noted the rise in the percentage of all faculty identifying as liberal going from 36.8 percent in 1989-90 to 50.3 percent in 2010-211, though it then edged down through 2016-2017 to 48.3 percent.21 That result becomes more troubling, however, given that in 1989 “far left” faculty were a paltry 5.2 percent, but by 2016-2017, had more than doubled to 11.6 percent. Thus, faculty self-identifying as liberal or far left actually spiked from 42 percent in 1989 to nearly 60 percent in 2016-2017.22 If by “liberal” those surveyed meant embracing fundamental ideals of freedom, declining academic liberalism is itself concerning.

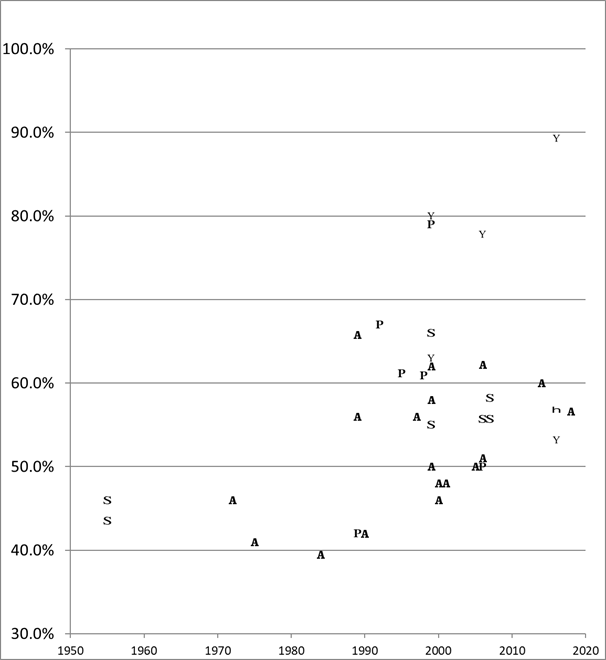

The overall picture these data present (fig. 1) suggests that a “leftward lurch” has taken place within academics, especially among social scientists.

Fig. 1. % of All Faculty (A), Social Scientists (S), Political Scientists (P), Psychologists and Social Psychologists (Y), or Historians (H) self-identifying as liberal, left (including far left), or Democratic, 1955-2018

If so, why did this leftward lurch take place?

Has Hiring Democratic Party Demographics Decreased Ideological Diversity?

A first potential explanation may be the increasing number of academics from demographics that lean left on average.

For instance, the proportion of female full-time political science faculty members almost tripled from 10.3 percent in 1980 to 28.6 percent in 2010.23 By February 2020, women made up about 37.4 percent of American Political Science Association (APSA) members.24 How much might an increase of roughly 27 points in the percentage of female political science faculty raise the percentage self-identifying as left, liberal, or Democratic, given that one study of liberal arts colleges found “only” 7.2 Democratic men for every Republican man, but 20.8 Democratic women for every one Republican woman?25

Similarly, the white proportion of full-time political science faculty dropped from about 93 percent in 1980 to about 75 percent in 2020. 26 In the 2018 election, 44 percent of white voters supported Democrats vs. 76 percent of non-white voters.27 That likely understates the partisan skew between white and non-white political scientists, given their overall 8.2:1 Democratic-to-GOP ratio.28 Regardless, if support for Democrats is indeed higher among non-white vs. white faculty, more non-white colleagues might help explain shifting partisan identification.

Structural evidence also suggests political science seeks to promote Democratic constituencies as opposed to underrepresented groups. As iconic political scientist James E. Campbell notes, “[t]he lengthy list of APSA ‘status’ committees includes blacks, Latinos, Asian Pacific Americans, women, lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgenders, but there is no committee on intellectual diversity (or on conservatives),”29 even though Asians are actually 83 percent over-represented among American faculty relative to broader U.S. society, while conservatives are underrepresented by a towering 74 percent—12 percentage points more than blacks.30 Similarly, why doesn’t APSA have a committee on Republicans, given that the ratio of Democrats to Republicans in liberal arts colleges is more than 10 to 1?31 Finally, for the record, why not a Christian committee, given that according to one analysis, non-Christian faiths are the most over-represented group in academics, at an astonishing 117 percent?32

Thus, data among political scientists in particular suggests that hiring more individuals from demographics that tend to favor the Democratic Party may be helping drive the leftward lurch among U.S. academics.

Does Political Science Hiring Call for Commitment to a Particular Ideology?

A second potential explanation might be that the academy signals a preferred ideology by explicitly favoring candidates who embrace racial, ethnic, and sex diversity in particular, rather than those who favor, for instance, ideological, partisan, methodological, socio-economic, class, religious, age, or geographic diversity.

Anecdotal evidence suggests this may be so. For instance, one school listed a “VISITING ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF AFRO-LATINX STUDIES” who should “embody the diversity of the United States as well as the global society in which we live.” The listing encourages application from, “women, racial and ethnic minorities, and other individuals who are underrepresented in the profession, across color, creed, race, ethnic and national origin, physical ability, gender and sexual identity, or any other legally protected basis.”33 Tellingly, religion, age, and political affiliation number among those legally protected classes, but were left out of the listing. Another school sought “faculty members whose scholarship, teaching, and on- and off-campus service demonstrate commitment to the educational benefits of a richly diverse community,” requiring applicants to “address how your scholarship, teaching, mentoring, and/or service might support the College’s . . . core commitment to diversity and inclusion.”34

Likewise, APSA’s 2011 benchmark diversity report bewails that so rarely does political science center on “alleviating inequality or advancing the cause of social justice,” 35 expressing concern that “[t]he tendency to accept its approaches as ‘objective’ science, for example, tends to inhibit the development of a more critical debate about the potential phenomenological bases of much empirical social science.” 36 Moreover, it decries “[t]he presumption that a group of individuals of mostly the same background . . . can comprehensively study the politics of those positionalities.” 37 Yet, Campbell (2019) points out, the report contained “not a single mention of ideological or intellectual diversity—and this in a profession whose raison d’etre is the intellectual understanding of politics.”

Finally, in a recent essay two academics assert, “lack of diversity perpetuates white male power in terms of the types of research our field produces and prioritizes,” because political science in particular “devalue[s] research pertaining to race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and identity, as well as qualitative work” as less “scientific.”38

These examples at least suggest that ideology is driving academic perceptions of what type of diversity matters.

Does Academic Hiring Favor Diversity Over Other Values?

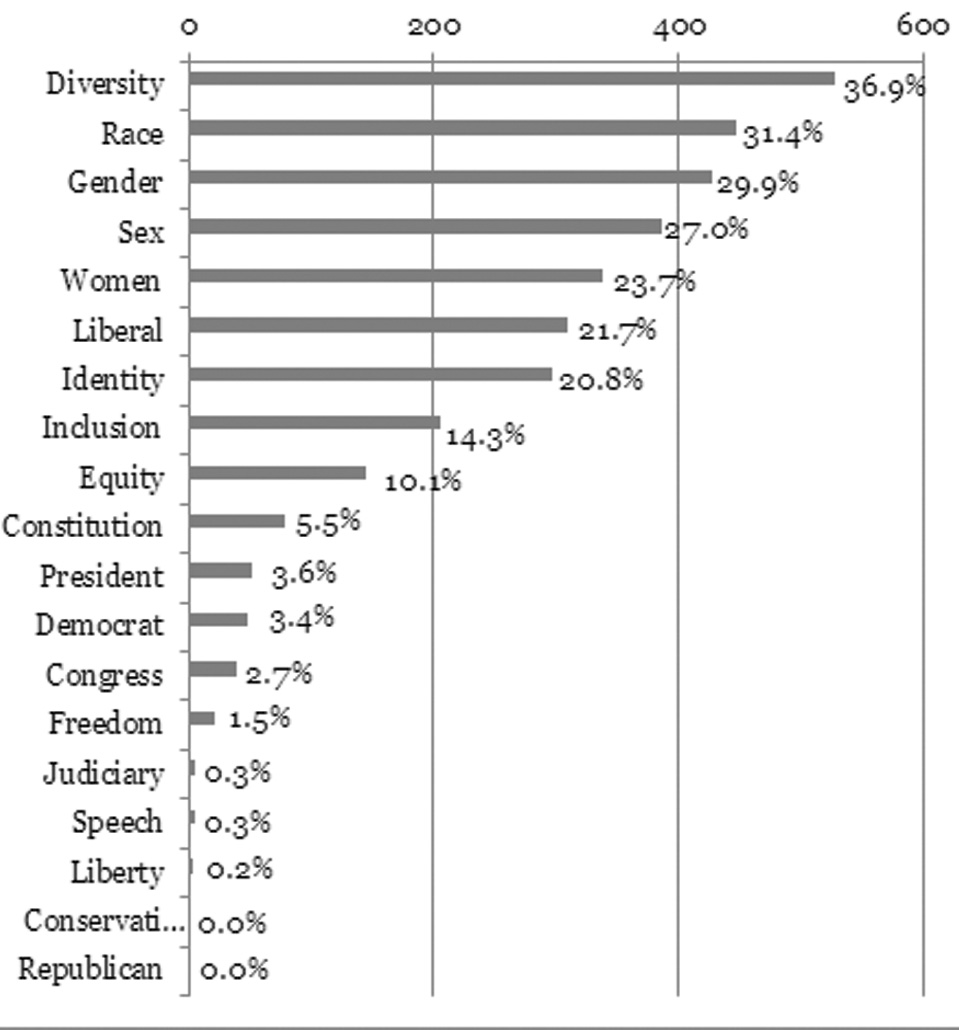

A third potential explanation of the “leftward lurch” may be that those hiring political scientists on average set diversity, however it is defined, above other values. To check, the author searched APSA’s eJobs database for terms denoting ideological concepts associated with the left as defined above (Diversity, Inclusion, Identity, Equity); historically marginalized groups (Race, Gender, Sex, and Women); traditionally liberal ideals as described above (Freedom, Liberty, Speech); American political institutions (President, Congress, Judiciary, and the Constitution); and America’s two main ideological and partisan pairs (Liberal, Conservative, Democrat, Republican).

Fig. 2. % of APSA eJobs Listings with Term, February 16, 2019

The results (fig. 2) suggest that those hiring political science educators may be more focused on diversity, race, gender, and sex than on liberty, freedom, and speech, and potentially, on key governmental institutions, parties, philosophies, or the Constitution.

This is not to say job descriptions necessarily seek those who teach diversity, inclusion, race, gender, or sex. Rather, these job descriptions are more likely to mention such qualifications relative to specialization in some specific institutions or commitment to liberty or freedom.

This is also not to say universities omitting those institutions from job listings provide no courses on them, nor that those applying might not be eminently qualified to teach such courses. It is to say, however, that if universities omitting those terms provide those classes, their job descriptions are attracting applicants to teach them who may not specialize in doing so.

Nor is there a monolithic meaning to these terms. “Liberal,” in addition to the definitions above, has at least three additional potential meanings: left-of-center, laissez-faire, and the support for the rounded education of free individuals allowing full participation in civic life, or “liberal arts”—and in one sample at least, “liberal” was used exclusively in that last sense.39

Finally, this is not to say these are the only words that might be selected for such an analysis. For instance, “tradition” outranked “equity,” though tradition was used in ways including contrasting a program’s approach to past approaches.40

Regardless, in 2019 those placing APSA job listings mentioned race or gender about 100 times as frequently as speech or the judiciary, and diversity about 200 times as frequently as liberty.

Conclusion

If diversity-driven hiring decreases ideological diversity in any of these ways, it diminishes the range of perspectives to which students are exposed, undercutting a key rationale for diversity itself.

With reverence for the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., perhaps we will one day live in a nation where academics “will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”41

1 Stanley Rothman, S. Robert Lichter, Neil Nevitte, “Politics and Professional Advancement Among College Faculty,” The Forum 3, no. 1 (2005).

2 Daniel B. Klein, Charlotta Stern, “Professors and Their Politics: The Policy Views of Social Scientists,” Critical Review 17 no. 3 (2005): 257–303.

3 Neil Gross, Solon Simmons, “The Social and Political Views of American Professors,” Harvard University and George Mason University, Working Paper, September 24, 2007.

4 Neil Gross, Solon Simmons (eds.), Professors and Their Politics (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014); J. Matthew Wilson, “The Nature and Consequences of Ideological Hegemony in American Political Science,” PS: Political Science & Politics 52 no. 4 (2019), 724-727.

5 Stanley S. Rothman, S. Robert Lichter, “The Vanishing Conservative—Is There a Glass Ceiling?” in The Politically Correct University: Problems, Scope, and Reforms, ed. Robert Maranto, Richard E. Redding, Frederick M. Hess (Washington, D.C.: The AEI Press, 2009); Gary A. Tobin, Aryeh K. Weinberg, “A Profile of American College Faculty: Political Beliefs and Behavior” (San Francisco: Institute for Jewish and Community Research, 2006); Gross and Simmons, 2007.

6 Mitchell Langbert, “Author Correction: Homogenous: The Political Affiliations of Elite Liberal Arts College Faculty,“ Academic Questions 31 (2018): 386.

7 Klein and Stern, 2005, 283; Wilson, 2019.

8 Paul Lazarsfeld and Wagner Theilens, Jr., The Academic Mind: Social Scientists in a Time of Crisis (Glencoe, Ill.: The Free Press, 1958), 162; Gross and Simmons 2007, 5 and 33; Rothman and Lichter, 2009.

9 Mitchell Langbert, Anthony J. Quain, Daniel B. Klein, “Faculty Voter Registration in Economics, History, Journalism, Law, and Psychology,” Econ Journal Watch 13, no. 3 (September, 2016): 422–51.

10 Rothman and Lichter, 2009; Gross and Simmons 2007, 34.

11 Christopher F. Cardiff, Daniel B. Klein, “Faculty Partisan Affiliations in All Disciplines: A Voter-Registration Study,” Critical Review 17 no. 3 (2005): 237–55; Rothman and Lichter, 2009; Klein and Stern, 2006; Wilson, 2019.

12 Langbert, 2018.

13 Lazarsfeld and Thielens, 1958; Rothman and Lichter, 2009.

14 Louis Hartz, The Liberal Tradition in America; an Interpretation of American Political Thought Since the Revolution, 2nd ed. (San Diego: Harvest, 1991), p. 4; Molly C. Michelmore, Tax and Spend: The Welfare State, Tax Politics, and the Limits of American Liberalism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014).

15 Princeton Survey Research Associates, National Survey on Government Endeavors, (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, November 9, 2001); Klein and Stern, 2005; Rothman, Lichter, Nevitte, 2005; Mark D. Mariani, Gordon J. Hewitt, “Indoctrination U? Faculty Ideology and Changes in Student Political Orientation,” PS: Political Science & Politics 41 no. 4 (2008): 773–83; Robert Maranto, Matthew Woessner, “Diversifying the Academy: How Conservative Academics Can Thrive in Liberal Academia,” PS: Political Science & Politics 45, no. 3 (2012): 469–74; Maria Konnikova, “Is Social Psychology Biased against Republicans?” The New Yorker, October 30, 2014; James E. Campbell, “The Trust Is Gone: What Ideological Orthodoxy Costs Political Science,” PS: Political Science & Politics 52 no. 3 (2019): 1-5.

16 Darren L. Linvill, Joseph P. Mazer, “Perceived ideological bias in the college classroom and the role of student reflective thinking: A proposed model,” Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 11, no. 4 (December 2011): 90–101.

17 E. B. Stolzenberg et al., Undergraduate teaching faculty: The HERI Faculty Survey 2016–2017 (Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute—2019), 16.

18 Shaena Engle, “UCLA Study Finds Growing Gap in Political Liberalism between Male and Female Faculty,” Higher Education Research Institute (HERI), October 27, 2002.

19 Rothman and Lichter, 2009, 66.

20 Jon Haidt, “New Study Indicates Existence of Eight Conservative Social Psychologists,” Heterodox Academy, January 7, 2016.

21 Stolzenberg et al., 18.

22 Ibid.; Klein and Stern 2009.

23 APSA, Political Science in the 21st Century: Report of the Task Force on Political Science in the 21st Century, October 2011.

24 APSA, “Membership Dashboard,” March 21, 2020.

25 Langbert, 2018.

26 APSA, Political Science in the 21st Century: Report of the Task Force on Political Science in the 21st Century, October 2011; APSA, “eJobs Online,” search performed on March 26, 2020.

27 CNN Politics, “Exit Polls,” 2018, retrieved March 5, 2019.

28 Langbert, 2018.

29 James E. Campbell, “The Trust Is Gone,” 1-5.

30 Musa al Gharbi, “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump,” The American Sociologist 49 no. 4 (2018): 496–519, cited in Wilson, 2019, and in “The Problem,” Heterodox Academy, retrieved March 28, 2020.

31 Langbert, 2018.

32 al Gharbi, 2018.

33 New York University, “VISITING ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF AFRO-LATINX STUDIES,” American Political Science Association, “eJobs Online,” search performed on March 5th, 2019.

34 Holy Cross, “Visiting Full-Time Faculty Position in American Politics,” APSA, “eJobs Online,” search performed on March 5, 2019.

35 APSA, 2011, 12.

36 APSA, 2011, 1.

37 APSA, 2011, 13.

38 Rebecca A. Reid and Todd A. Curry, “Are We There Yet? Addressing Diversity in Political Science Subfields,” PS: Political Science & Politics 52 no. 2 (2019): 283.

39 APSA, “eJobs Online,” 2020.

40 Ibid.

41 Rev. Martin Luther, King, Jr., “I have a dream . . . ” speech at the “March on Washington,” 1963.