David Rozado holds a Ph.D. in Computer Science from the Autonomous University of Madrid and is a widely published author in that field. Prof. Rozado has been teaching at New Zealand’s Otago Polytechnic since 2015; [email protected]. His research interests are computational content analysis and accessibility software. Rozado last appeared in these pages with “Prejudice and Victimization Themes in New York Times Discourse: A Chronological Analysis,” in spring 2020.

Introduction

Previous scholarly literature has documented a marked increase of words denoting prejudice and social justice themes in news media content.1 This work investigates the prevalence dynamics of such terms in academic papers published in all fields of knowledge. We use the Semantic Scholar Open Research Corpus (SSORC) containing, as of 2020, over 175 million published scholarly articles and associated metadata.2 We quantify the prevalence of words denoting prejudice against ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, minority religious sentiment, age, body weight and disability in SSORC abstracts over the period 1970-2020. We then examine the relationship between the prevalence of such terms in the academic literature and their concomitant prevalence in news media content. Finally, we also analyze the temporal dynamics of an additional set of terms associated with social justice discourse in both the scholarly literature and in news media content. Taken together, these analyses allow us to illuminate the chronological dynamics of prejudice and social justice themes in academic discourse as well as their relationship with news media content.

Previous work published in this journal documented an abrupt increase in the prevalence of prejudice-denoting terms in the New York Times. A follow-up analysis confirmed the trend across forty-seven news media outlets.3 Critically, that paper also revealed that the rising trend preceded the 2015 emergence of Donald Trump on the U.S. political scene. In general, the abrupt increase started within the 2010-2014 time frame and remained at historical highs through at least the first five months of the Biden Administration starting in January 2021.4

Over the same temporal period (2010-2019), public opinion surveys show increasing public concern in the U.S. about prejudice, particularly among voters of the Democratic Party.5 Paradoxically, other longitudinal public opinion surveys have reported a decrease in overt prejudicial attitudes in U.S. society since the 1970s.6 Consequently, the role of news media discourse in shaping public concern about prejudice, as predicted by agenda-setting theory,7 has been investigated.8 Similarly, characterizing the prevalence of prejudice-denoting terms in the scholarly literature as well as scrutinizing whether academic content shapes news media discourse, or vice versa, is also worthy of investigation.

This work will focus on analyzing the usage trends of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse in the scholarly literature. Those trends will then be compared with news media usage of the same terms in order to scrutinize the relationships in content prevalence between both cultural institutions: the academy and news media.

Methods

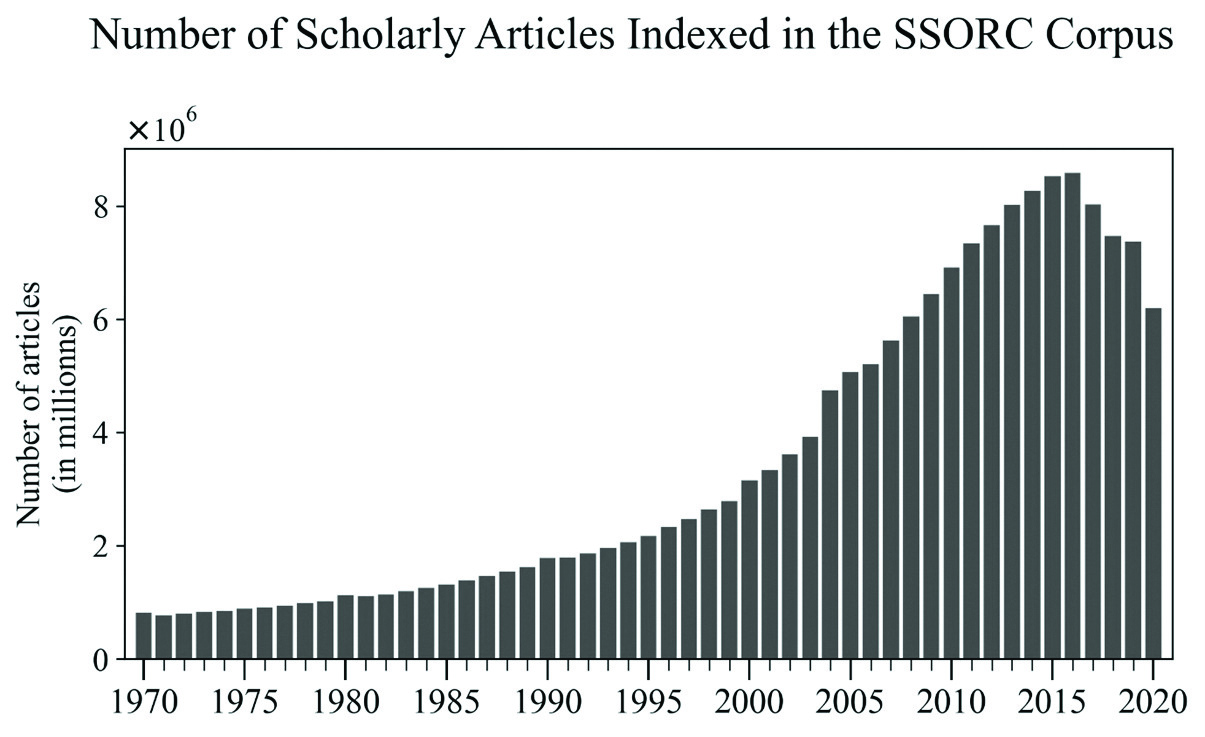

The list of scientific abstracts analyzed in this work was taken from the Semantic Scholar Open Research Corpus (SSORC).9 The corpus contains, as of 2020, over 175 million academic abstracts, and associated metadata, published in all fields of knowledge. The raw data is provided by Semantic Scholar in accessible JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) format. The number of articles per year indexed in the SSORC corpus is shown in Figure 1.

Textual content included in our analysis is circumscribed to the scholarly articles’ titles and abstracts and does not include other article elements such as main body of text or references section. Thus, we use frequency counts derived from academic articles’ titles and abstracts as a proxy for word prevalence in those articles. This proxy was used because the SSORC corpus does not provide the entire text body of the indexed articles. Targeted textual content was located in JSON data and sorted by year to facilitate chronological analysis. Tokens were lowercased prior to estimating frequency counts.

Yearly relative frequencies of a target word or n-gram in the SSORC corpus were estimated by dividing the number of occurrences of the target word/n-gram in all scholarly articles within a given year by the total number of all words in all articles of that year. This method of estimating word frequencies accounts for variable volume of published academic articles over time. This approach has been shown before to accurately capture the temporal dynamics of historical events and social trends in news media corpora.10

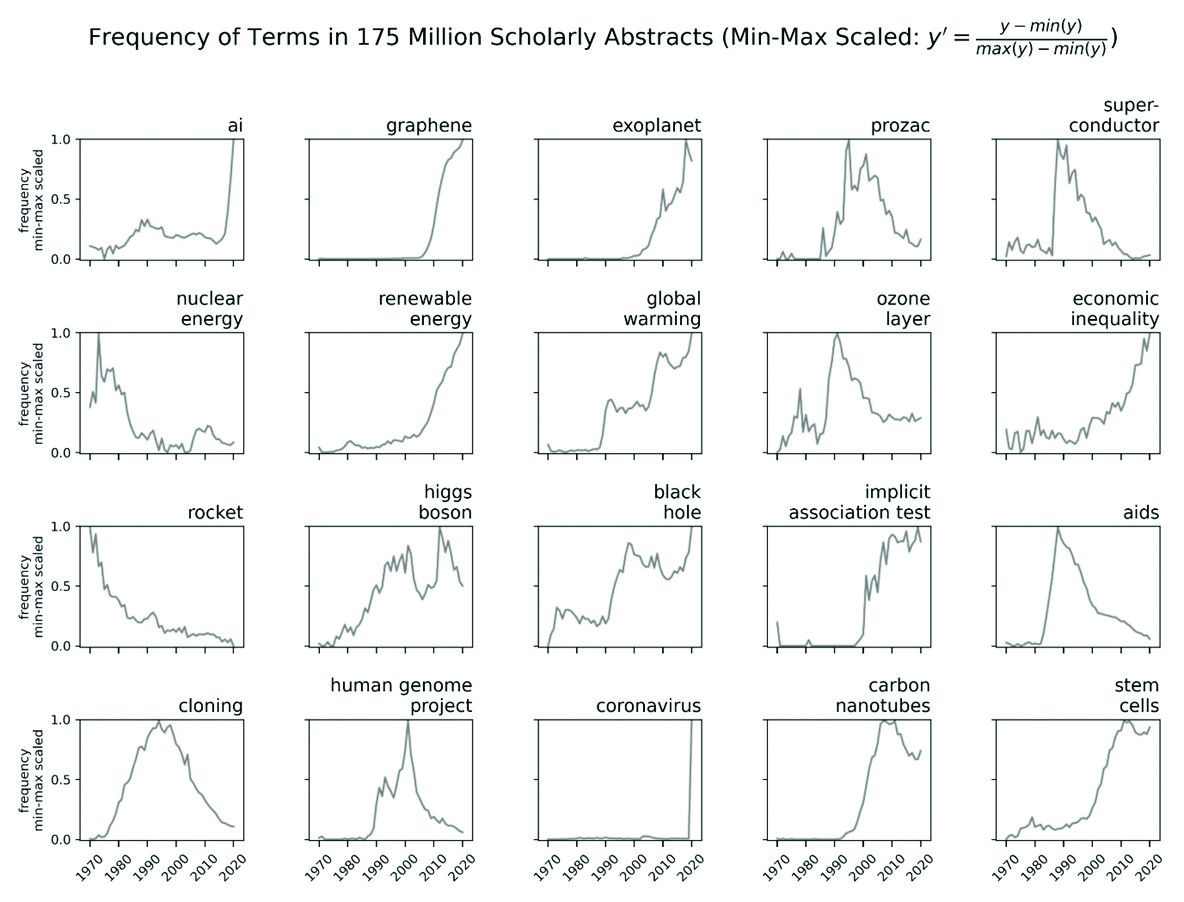

It is possible that a small percentage of scholarly articles in the SSORC corpus contain incorrect or missing data. For earlier years in the SSORC corpus, abstract information is sometimes missing and only article title information is available. Overall, however, we are confident that our frequency metrics are representative of word prevalence in academic content, see Figure 2 as an illustrative example.

We used factor analysis to derive common variability among all the time series of words frequency data. This was done to uncover underlying factors encapsulating the main trends embedded in the raw time series data. Factor analysis of frequency counts time series was carried out only after Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test confirmed the suitability of the data for factor analysis. A single factor derived from the frequency counts time series of prejudice-denoting terms was extracted from each corpus (academic abstracts and news media content). The same procedure was applied for the terms denoting social justice discourse. A factor loading cutoff of 0.5 was used to ascribe terms to a factor. Chronbach alphas to determine if the resulting factors appeared coherent were extremely high (>0.95).

Our methodology for the analysis of news media written content has been described extensively elsewhere.11

The analysis scripts, the IDs of each analyzed abstract in the SSORC corpus and the counts of target words and total words for each scholarly and news media article analyzed are provided as supplementary material in electronic form.12

Prevalence of Prejudice-denoting Terms in the Scholarly Literature

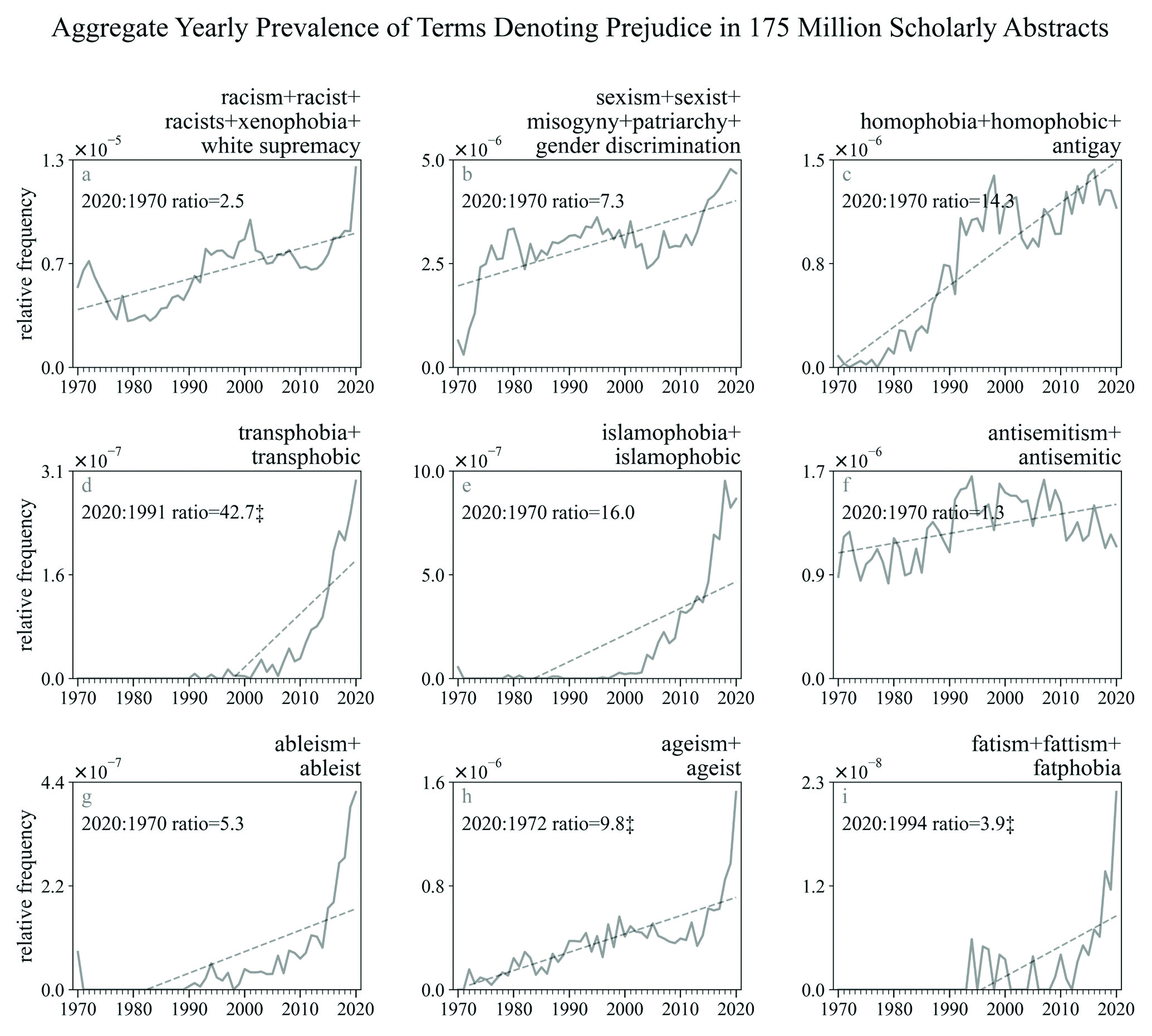

The aggregate relative frequencies in academic abstracts of sets of terms denoting different prejudice types is shown in Figure 3. Ethnic and gender prejudice are the most prevalent prejudice topics in scholarly content. An increasing trend in the prevalence of most prejudice types since the 1970s is apparent. However, the specific temporal dynamics of each prejudice theme are often distinct. A marked rise in prevalence between 2010 and 2020 is noticeable across most prejudice types.

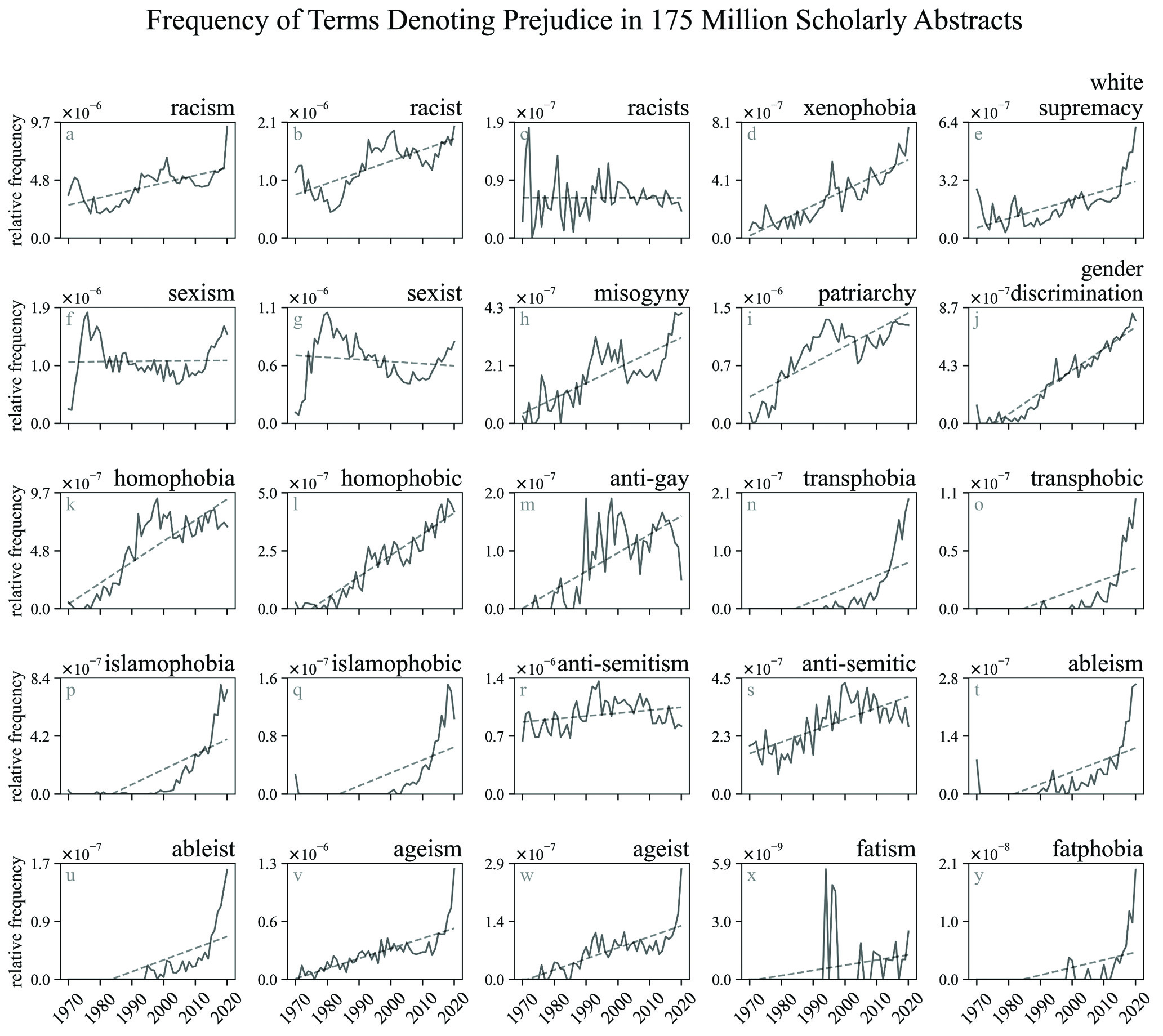

Aggregating the relative frequencies of related terms denoting specific prejudice types is useful to provide a quantification of the overall prevalence of the theme in the corpus. However, such aggregate metrics can obscure the temporal dynamics of specific terms within the set, since the dynamics of lower prevalence terms can be masked by terms with larger prevalence. Figure 4 shows the individual dynamics of the terms displayed in Figure 3.

It is apparent that the dynamics of individual terms in Figure 4 do not always overlap with the trends of the sum of related terms in Figure 3. The aggregated nonlinear trend displayed in Figure 3a for the ethnic prejudice theme is dominated by the words in the set with the largest relative frequencies: racism (Figure 4a) and racist (Figure 4b). In contrast, a term with lower relative frequency, xenophobia (Figure 4d), displays a pattern of steady linear growth since the 1970s. Similarly, terms such as misogyny (Figure 4h), patriarchy (Figure 4i) and gender discrimination (Figure 4j) have been growing steadily in the academic literature since the 1970s. But such individual term dynamics are obscured in the aggregate metric of Figure 3b.

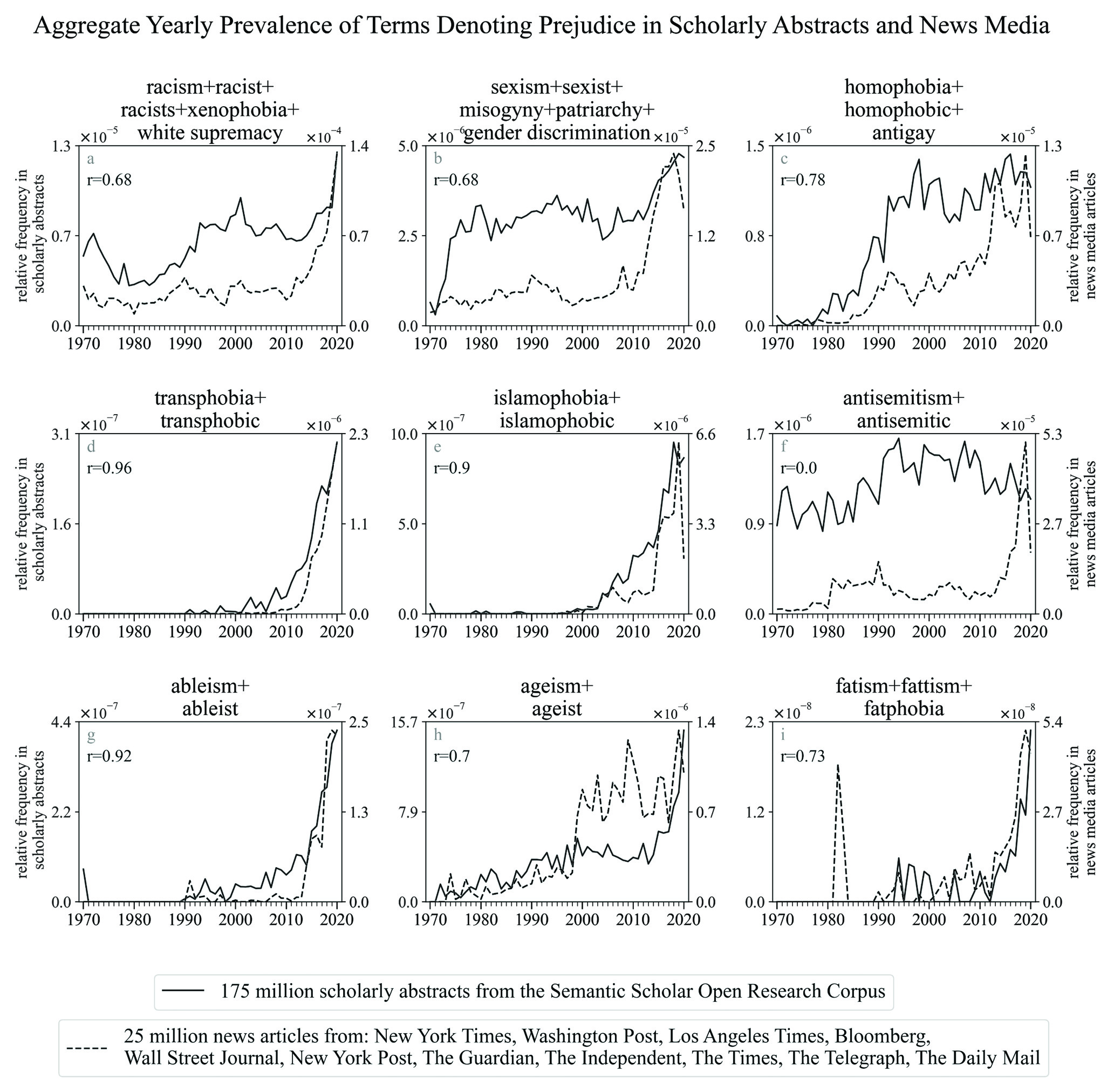

We next examine the relationship between the prevalence of terms denoting specific prejudice types in scholarly abstracts and the prevalence of those terms in news media written content, see Figure 5. Overall, prejudice-denoting terms tend to be more prevalent in news media content than in the academic literature. For most prejudice types, there is a moderate to high correlation between the prevalence of such words in academic and news media content. A striking pattern in Figure 5 is that news media content displays a simultaneous abrupt increase in the prevalence of most prejudice types starting at some point between 2010 and 2015. Academic content also displays an increase in the prevalence of several prejudice types post-2010 but it is neither as marked nor as uniform across different prejudice types.

Often, terms denoting a new prejudice type appear to emerge first in the academic literature and then spread to news media. Such is the case in the 1970s for the prejudice types of homophobia and ageism. Similar dynamics occur for Islamophobia, ableism, and transphobia in later years. Fatphobia however displays the opposite dynamic, with pioneering occurrence happening first in news media and emergence in the academic literature happening afterwards.

Sometimes, prevalence growth in the academic literature for a specific prejudice-type is followed in close temporal proximity by growing prominence in news media content. This is the case for racism and homophobia in the 1980s and for transphobia post-2010. For gender and ethnic prejudice-denoting terms however, increasing prevalence in the academic literature in the 1970s and 1990s respectively did not translate into increases in prevalence in news media content immediately thereafter. The antisemitism prejudice theme displays the largest degree of decoupling between news media and scholarly content. The theme has been relatively stable in prevalence in the academic literature over the last five decades. The prevalence of the antisemitism topic has also been stable for many decades in news media content but it rises abruptly in the 2010s.

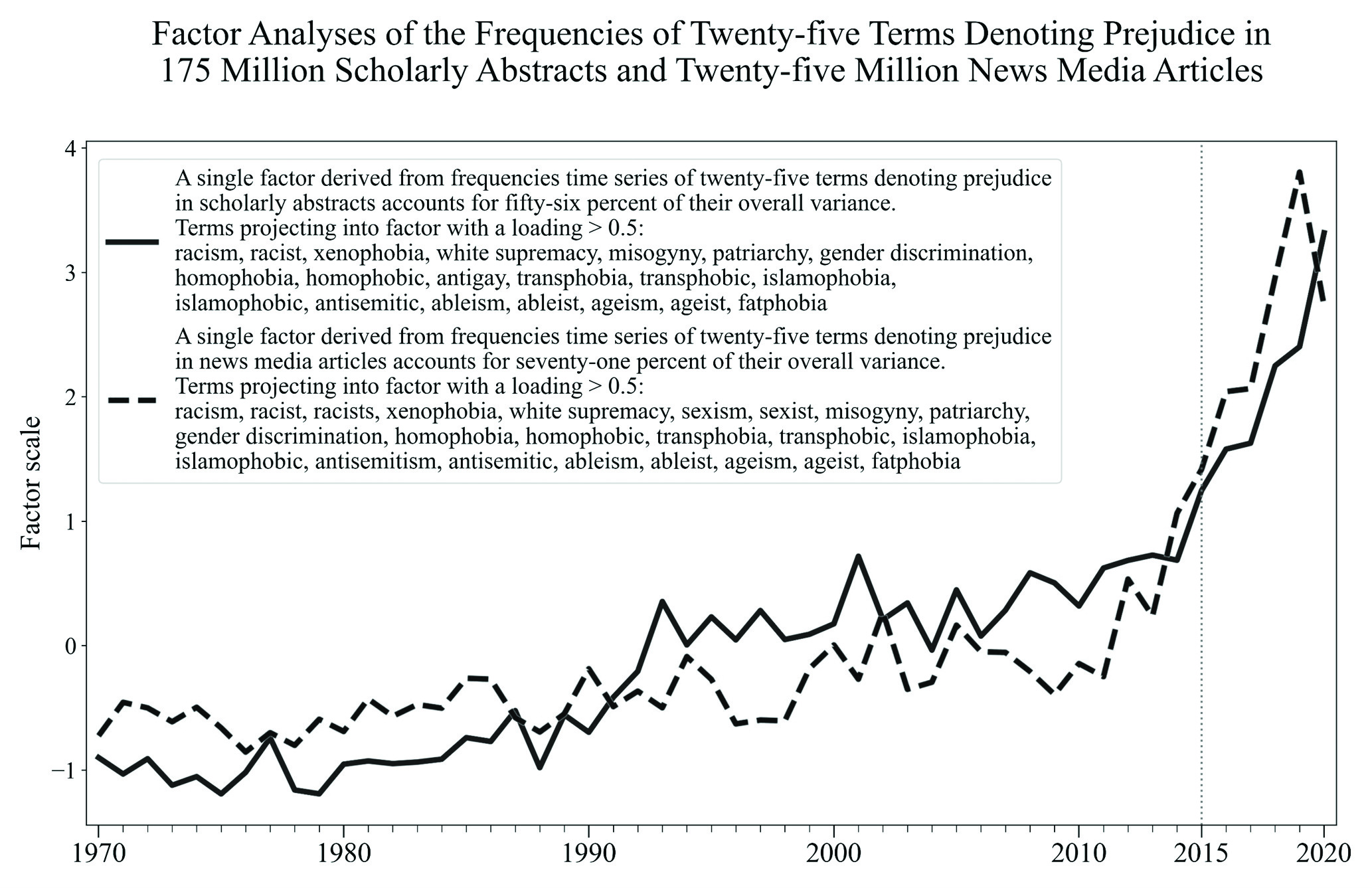

We next apply factor analysis to all the time series of prejudice-denoting terms in scholarly content and news media discourse. A single factor (blue solid trend in Figure 6) encapsulates 56 percent of the overall variance of the 25 prejudice-denoting terms in scholarly content. The factor displays steady growth from the 1980s until around the early 2010s and a marked increase post-2014. A single factor (dashed orange trend in Figure 6) captures 71 percent of the overall variance of the twenty-five prejudice-denoting terms in news media articles. This factor appears very stable from the 1970s until 2010 and then displays an abrupt increase post-2010. The abrupt increase in prevalence post-2010 is apparent in both scholarly and news media content but the jump appears more marked and seems to occur slightly earlier in news media content. Interestingly, stationarizing both time series and doing Granger-Causality tests (ssr-based Chi-squared test, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons) of whether the news media factor is predictive of the scholarly content factor are statistically significant (p<0.01) for year lags 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. None of the Granger-Causality tests in the reverse direction (i.e. testing whether scholarly content predicts news media content) are statistically significant for the same year lags.

Prevalence of Social Justice Terms in the Scholarly Literature

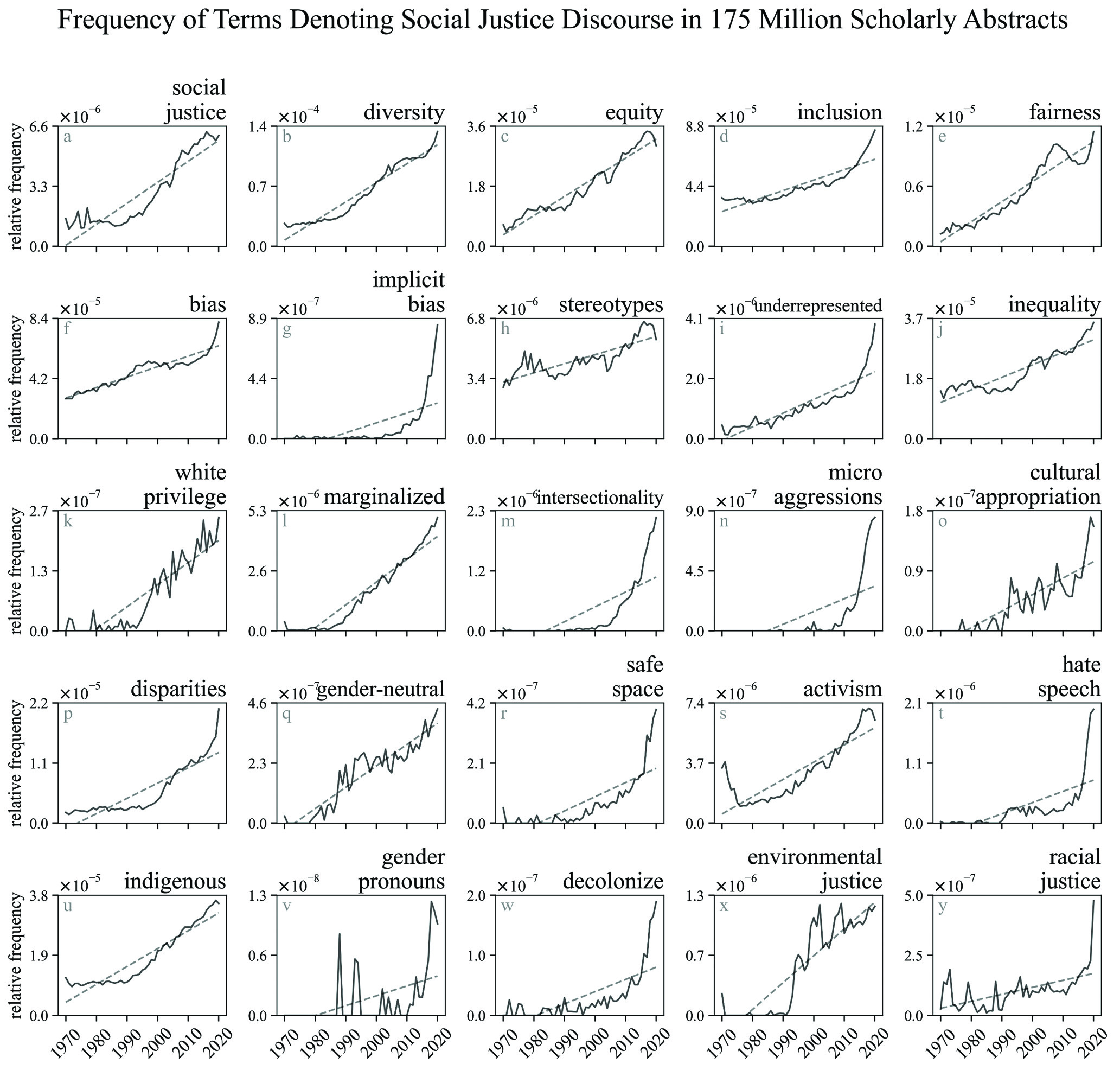

We next examine the prevalence in academic abstracts of an additional set of terms associated with social justice discourse, see Figure 7. It is apparent from the figure that there is an overall tendency of the analyzed terms to have been growing in prevalence over the last fifty years.

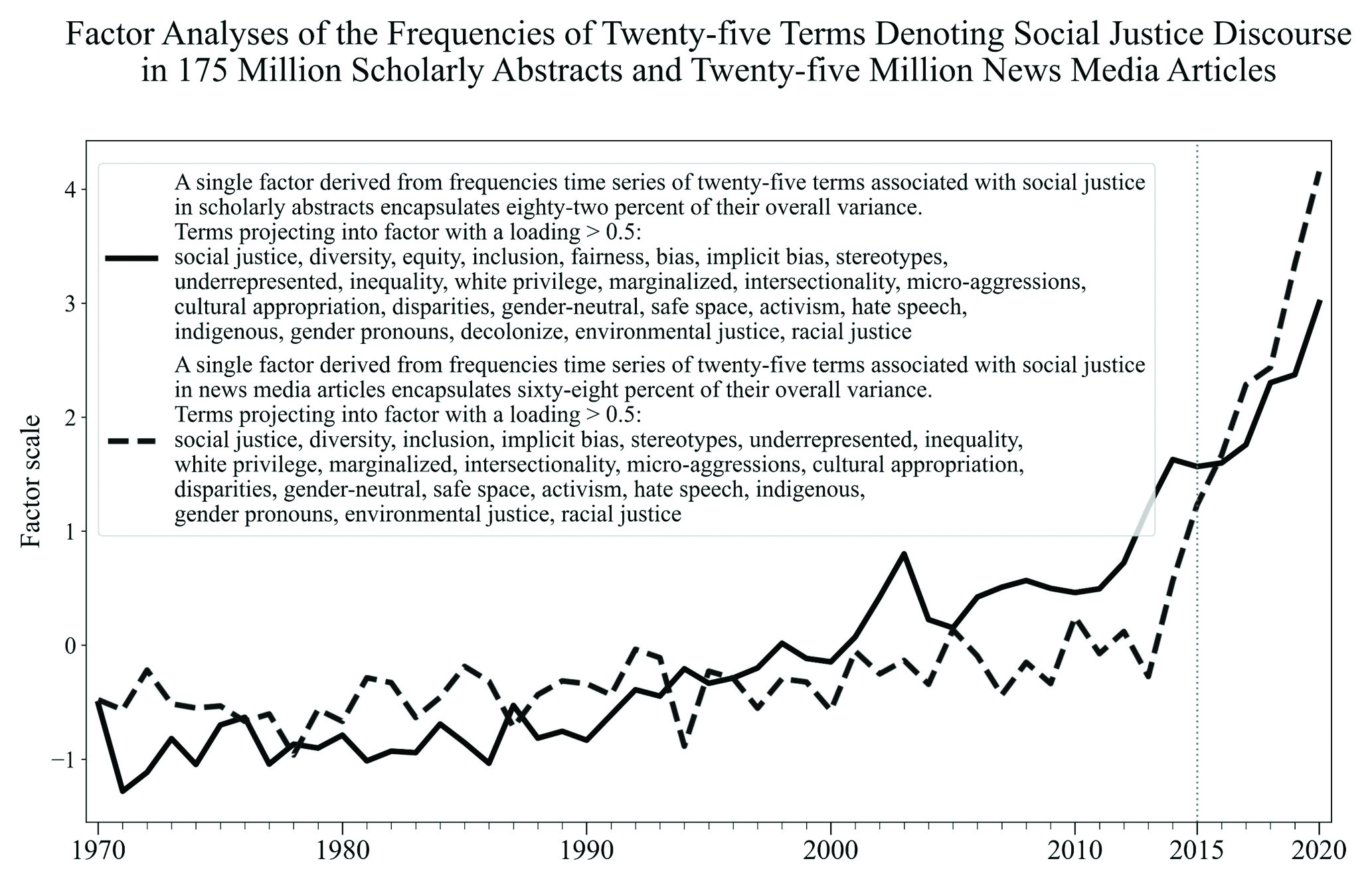

A factor analysis of the terms denoting social justice discourse in scholarly and news media content is shown in Figure 8. Just one factor captures 82 percent of their overall variance in scholarly content. A single factor captures 68 percent of their overall variance in news media content. The factor derived from scholarly content displays steady growth from the 1980s until the early 2010s at which point the rate of growth of the factor increases substantially. In contrast, the factor derived from the news media content is relatively stable from the 1970s until around 2013. Post-2013, it starts to grow abruptly. Both factors display very similar patterns to those already documented previously for the factor analysis of the prejudice-denoting terms. Stationarizing both time series and doing Granger-Causality tests (ssr-based Chi-squared test, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons) of whether the news media factor is predictive of the scholarly content factor are non-significant (p<0.01) for year lags 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. Similarly, the Granger-Causality tests in the reverse direction (scholarly contentnews media) are also non-significant for the same year lags.

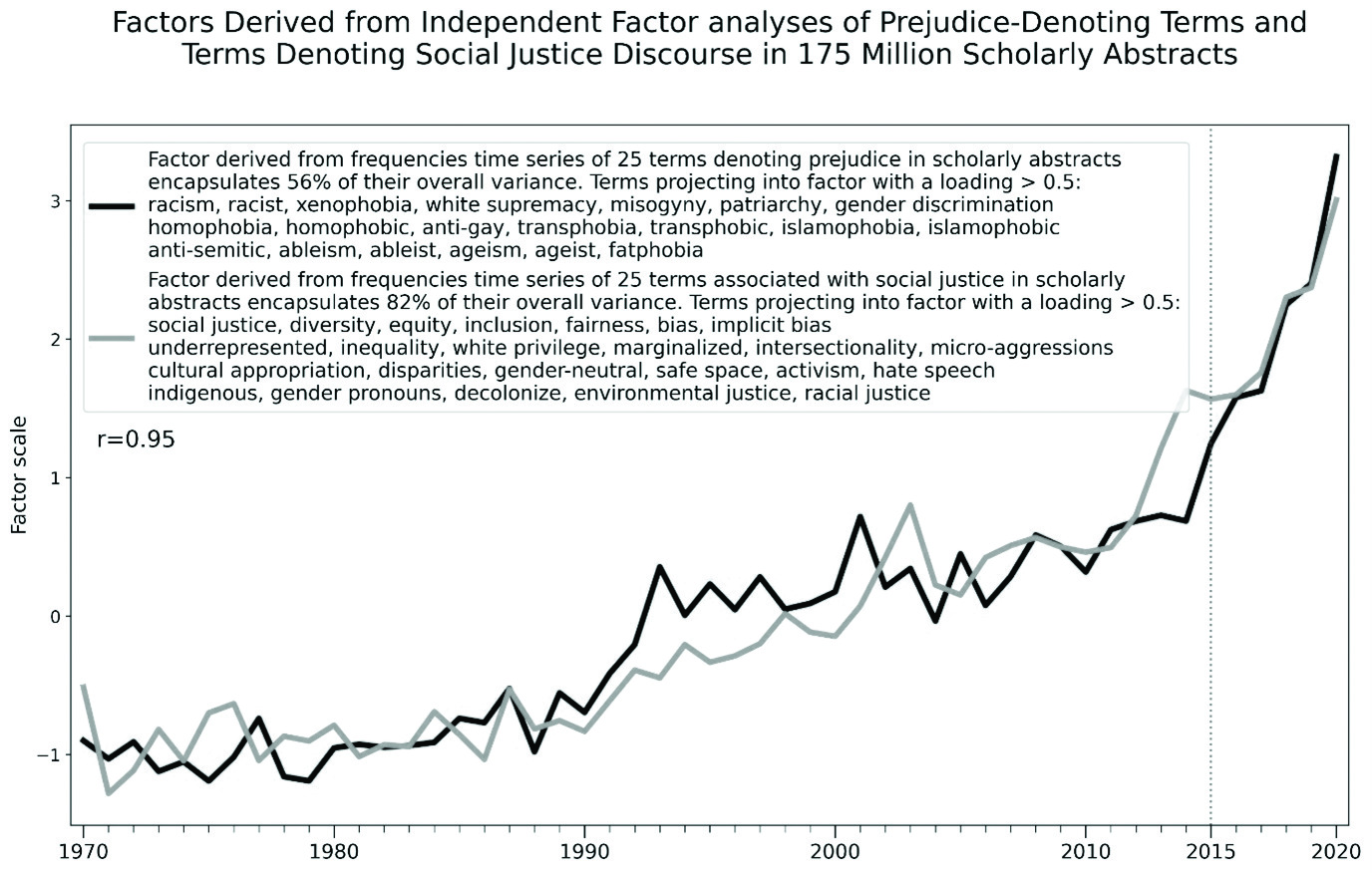

Finally, Figure 9 shows a comparison side-by-side of the two factors derived from the twenty-five prejudice-denoting terms and the twenty-five terms denoting social justice discourse in academic content. The correlation between both factors is very large (Pearson r= 0.95). As noted above, both factors grow steadily since the 1980s until the early 2010s. Post-2010, both factors grow abruptly. Stationarizing both time series and doing Granger-Causality tests (ssr-based Chi-squared test, Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons) of whether the prejudice factor is predictive of the social justice factor are statistically significant (p<0.01) for year lags 3, 4 and 5. None of the Granger-Causality tests in the reverse direction (i.e. testing whether the social justice factor predicts the prejudice factor) are statistically significant for the same year lags 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Discussion

We have presented a pioneering analysis about the prevalence of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse in the academic literature and its concomitant prominence in news media content. The patterns emerging from the analysis are multifaceted and defy an overarching simple explanation.

The factor analyses on usage frequencies in the academic literature of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse revealed that the prevalence of prejudice-denoting terms and terms associated with social justice discourse has been growing steadily in the scholarly literature since the 1980s. This is mostly not the case in news media content where the prevalence of such terms was mostly flat from 1970 to 2010. However, post-2010, the prevalence of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse increases abruptly both in the scholarly literature and in news media content. The extremely large correlation (r= 0.95, see Figure 9) between the factors accounting for the usage of prejudice and social justice associated terms in scholarly content suggests an underlying latent source that simultaneously influenced the prevalence of prejudice-denoting terms and terms associated with social justice discourse.

There is considerable heterogeneity in the chronological prominence of specific prejudice types in the academic literature. For some, such as prejudice due to gender identity, sexual orientation, Islamic religious faith, age or body ability, the scholarly literature seems to have pioneered the usage of terms denoting those types of prejudice while news media incorporated those terms in their lexicon in subsequent years.

Increasing prevalence of prejudice-denoting terms in academic content has been occasionally followed shortly afterwards by increasing prevalence of such terms in news media content (for instance ethnic and sexual orientation prejudice in the 1980s). In other instances however, increasing prominence in academic content of prejudice-denoting terms was not immediately mirrored in news media content (i.e. gender prejudice in the 1970s or ethnic prejudice in the 1990s).

The results of the Granger-causality tests to examine the temporal association between news media and academic content prevalence of prejudice-denoting words are intriguing since they suggest that it is news media usage of such terms that is predictive of next years’ usage of the same words in academic content. A plausible interpretation of these results is that academics are reactive to the prominence of prejudice topics in news media content. An alternative explanation is that both journalists and academics are reacting to lurking variables influencing thematic prominence of prejudice-denoting terms in scholarly and news media content but with different latencies due perhaps to the longer time cycle of academic publishing.

To conclude, our results suggest that the prevalence in the academic literature of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse has been growing steadily and diffusely since the 1980s but that such prevalence accelerated abruptly after 2010. Furthermore, the overall increasing prevalence in academic content since the 1980s until 2010 of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse is largely not mirrored in news media content. However, the abrupt increase in the prevalence of such terms post-2010 is apparent in both academic and news media content, but it is more acute in news media.

Interestingly, news media usage of terms denoting prejudice is predictive of the usage of such terms in academic content in subsequent years, which suggests that academics could be influenced in their choosing of research topics by the saliency of themes in news media. The relationship however appears complex, as for many prejudice types, words denoting new prejudice types seem to emerge first in academic content and spread afterwards to news media content. Future studies should try to quantify whether the trend of increasing usage of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse in academic and news media content has also spread to other influential social institutions such as political parties, think tanks, supranational organizations or the entertainment industry.

1 David Rozado, “Prejudice and Victimization Themes in New York Times Discourse: A Chronological Analysis,” Academic Questions 33, no. 1 (March 1, 2020): 89–100,; David Rozado, Musa Al-Gharbi, Jamin Halberstadt, “Prevalence of Prejudice-Denoting Words in News Media Discourse: A Chronological Analysis,” Social Science Computer Review, July 27, 2021, 08944393211031452, https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393211031452.

2 Waleed Ammar et al., “Construction of the Literature Graph in Semantic Scholar,” in NAACL, 2018, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/N18-3011; John Lee, Ying Cheuk Hui, and Yin Hei Kong, “Semantic Scholar Open Research Corpus,” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, April 2016, https://academic.oup.com/dsh/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/llc/fqu052.

3 Rozado, “Prejudice and Victimization Themes in New York Times Discourse”;

Rozado, Al-Gharbi, and Halberstadt, “Prevalence of Prejudice-Denoting Words in News Media Discourse.”

4 David Rozado, Musa Al-Gharbi, Jamin Halberstadt, “Our Research Shows the ‘Great Awokening’ Preceded Trump—and Outlasted Him, Too | Opinion,” Newsweek, September 7, 2021.

5 Pew Research Center, “Democrats Increasingly View Racism and Sexism as Very Big National Problems; Larger Shares in Both Parties Say Drug Addiction Is a Major Problem,” Pew Research Center (blog), October 22, 2018; Pew Research Center, “More Now See Racism as Major Problem, Especially Democrats,” Pew Research Center (blog), August 29, 2017.

6 Krysan, M., Moberg, S., “Trends in Racial Attitudes,” University of Illinois Institute of Government and Public Affairs., August 25, 2016; Sarah Patton Moberg, Maria Krysan, Deanna Christianson, “Racial Attitudes in America,” Public Opinion Quarterly 83, no. 2 (September 12, 2019): 450–71, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz014; Kelsey D. Meagher, Xiaoling Shu, “Trends in U.S. Gender Attitudes, 1977 to 2018: Gender and Educational Disparities,” Socius 5 (January 1, 2019): 2378023119851692, https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119851692; Daniel J. Hopkins and Samantha Washington, “The Rise of Trump, The Fall of Prejudice? Tracking White Americans’ Racial Attitudes Via A Panel Survey, 2008–2018,” Public Opinion Quarterly 84, no. 1 (July 9, 2020): 119–40, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfaa004.

7 Dennis T. Lowry, Tarn Ching Josephine Nio, Dennis W. Leitner, “Setting the Public Fear Agenda: A Longitudinal Analysis of Network TV Crime Reporting, Public Perceptions of Crime, and FBI Crime Statistics,” Journal of Communication 53, no. 1 (2003): 61–73, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2003.tb03005.x; Maxwell McCombs, “A Look at Agenda-Setting: Past, Present and Future,” Journalism Studies 6, no. 4 (November 1, 2005): 543–57, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700500250438.

8 Rozado, “Prejudice and Victimization Themes in New York Times Discourse”;

Rozado, Al-Gharbi, and Halberstadt, “Prevalence of Prejudice-Denoting Words in News Media Discourse.”

9 Ammar et al., “Construction of the Literature Graph in Semantic Scholar”; Lee, Hui, and Kong, “Semantic Scholar Open Research Corpus.”

10 Rozado, Al-Gharbi, and Halberstadt, “Prevalence of Prejudice-Denoting Words in News Media Discourse.” Social Science Computer Review, July 27, 2021, 08944393211031452, https://doi.org/10.1177/08944393211031452.

11 Rozado, Al-Gharbi, Halberstadt, “Prevalence of Prejudice-Denoting Words in News Media Discourse”; David Rozado, “Prevalence in News Media of Two Competing Hypotheses about COVID-19 Origins,” Social Sciences 10, no. 9 (September 2021): 320, https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10090320. Rozado, D., & Kaufmann, E. (2022). The Increasing Frequency of Terms Denoting Political Extremism in US and UK News Media. Social Sciences, 11(4), 167.

12 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5832064