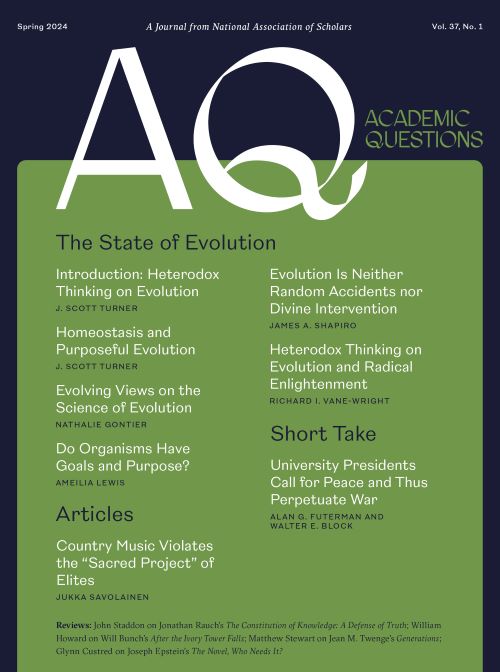

The Novel, Who Needs It? Joseph Epstein, Encounter, 2023, pp. 152, $16.39 hardbound.

The Liberal Arts in Higher Education

The aim of higher education, along with preparing students for a specific profession, is to broaden their general knowledge in order to make them well-rounded individuals and, hopefully, better citizens. This is done by means of the general studies curriculum, also called liberal education, which includes courses in the physical sciences, mathematics, the social sciences, and the humanities. Knowledge of the physical sciences (biology, chemistry, physics, astronomy, etc.) makes students better able to understand the physical world around them, as well as acquainting them with the scientific method. Knowledge of mathematics also has a place in the curriculum: it is its own distinctive form of thinking, but also necessary in scientific investigation and exposition.

Courses in the social sciences (sociology, economics, political science, geography, anthropology, and history) familiarize the student with the social environment and, in the case of history, provide knowledge of the past to better understand the present and prepare for the future. The humanities (philosophy, music, the visual arts, and literature) acquaints students with the major works of the mind and the creative hand of others. Courses in those subjects also show students how to evaluate and better appreciate those works by seeing how they have been crafted to achieve their effect—and perhaps also to stimulate the students’ own creativity.

By learning about those disciplines and how they are studied, students learn the value and the skills of scholarship, skills which will improve their ability to analyze and critically evaluate the social, political, and economic issues of the day. Students also learn how to formulate arguments, how to solve problems, and how to communicate more effectively. In the course of their studies, students will encounter a range of opinions and learn how to evaluate them in terms of recognized principles of logic and evidence, and how to rationally argue for the positions they favor and against those they oppose. All this forms a useful context for the later practice of whatever field they choose as their major, as well as a means of personal enrichment. As Michael S. Roth puts it in Beyond the University (2015), liberal education “increases our capacity to understand the world, contribute to it, and reshape ourselves.” And “when it works”, he says, “it never ends.”

Language and Stories

Language lies at the heart of all those disciplines, for language plays a crucial role in cognition, and more specifically in rational thinking and how problems might best be solved. Systematic rational thought is formalized in the discipline of logic which has been described as the science of correct reasoning. And rhetoric is the art of effective and persuasive speaking and writing. Both have their place in a general studies curriculum. Some universities have also focused on the practical application of formal logic with courses on “clear” or “critical thinking,” and on the application of rhetoric in courses on English composition and public speaking.

Language not only serves as a means of thinking and communicating, it is also the medium of artistic expression, for as linguist Edward Sapir once said, marble, bronze, or clay is the material of sculptures, paint the material of painters, and language the medium of literature.1 The field of literature has its own department in the university, typically as part of general education’s humanities curriculum.

The essence of literature is the story, whether told in prose, poetry, or drama. Stories and storytelling are basic to the human experience going back to the dawn of human consciousness. One can imagine a small group of people in prehistoric times lying under a star filled night sky, or sitting around a fire in the shelter of a cave listening to a man tell of the hunt which has provided them with meat for their subsistence. It's been said that “facts become alive when embedded in compelling stories,” so at some point long ago, story tellers began using the elements of ordinary speech—lexical and grammatical variants, pauses, different intonations, along with tropes—to make their stories more effective. As Roth has said, bare facts can become vivid when they are embedded in narratives,

Another form of storytelling with its roots in preliterate times is the epic. These are long narratives about the deeds of legendary figures and notable events of the past; stories which were composed and recited, or sung, by bards before live audiences. In early times when there was no writing, formulaic expressions and verse patterns were used both to compose and to memorize the stories which were told. This meant that each performance was different in some way while the story told remained essentially the same. The skills of the bard therefore involved verse making and recitation or singing, perhaps accompanied by a musical instrument, as well as transmitting history in the form of the epics they told. As oral historians and entertainers, those ancient reciters/singers occupied an important place in their societies. With the advent and the spread of writing, some epics were recited to scribes who wrote them down, thus becoming a part of written literature.

The best-known epics in the Western tradition are the Iliad and the Odyssey which were passed down orally for some five centuries before one of the several versions was written down and passed into the realm of written literature. Epic poems were also known in the Anglo-Saxon tradition in the story of Beowulf, in Spain in El Cid, and in Germany the Nibelungenlied. In the later Middle Ages new elements were added to the stories sung and told in that tradition, thus giving rise to the medieval romance. Those were adventure stories about knights on horseback who set forth in search of adventure, or to accomplish some mission which involved slaying dragons and confronting other formidable opponents. Those stories incorporated such features as heroic deeds, chivalry, religious piety, historic events, magical elements, and courtly love in which a lady fair played a major role.

Around 1200 a shorter version appeared known as the lay. Some of those romances drew on the ancient Celtic tales of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Perhaps the best known is Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, composed in the late fourteenth century. The earliest romances were composed in verse. Those after 1350 were in either verse or prose and after 1450 more of them were composed in prose. Some romances were written down, but most were told, or sung, by minstrels before audiences at court and in banquet halls.

In the fifteenth century literacy began to expand beyond the small group of clergy, lawyers, clerks, scribes, and academics who were literate because of their professions, to more people among the gentry and the growing middle class of merchants and tradesmen, so that copies of romances and other works were produced and distributed. The last of the medieval romances was one of the Arthurian stories, Malory’s Morte Darthur, which appeared in 1469. By that point this genre was falling out of favor among readers, marking the end of the medieval romance. At this time a new way of writing called the narrative poem written in the style of the romance, such as Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (c. 1382-1400) and William Langford’s Pier’s Ploughman (c.1370-1386), as well as the work of the Pearl Poet.

In 1440 Johannes Gutenberg assembled the first printing press, and by the end of the century his invention had spread across Europe, and with it a Latin translation of the Bible known as the Gutenberg Bible, the earliest major book mass produced by printing. In 1476 William Caxton established the first printing press in England, and the following year produced the first book printed in English, marking the start of a growing publishing industry.

The Novel Genre

The kind of storytelling we call the novel was possible only after the invention of printing and the general increase in literacy, and with it a publishing industry which could meet the increasing demand for reading material. According to many scholars the first modern novel is Don Quixote written by the Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616) and published in two parts in the early seventeenth century (1605 and 1615). It is a picaresque novel written in prose which mocked the medieval romance and what it represented; a literary statement which marked the end of the Middle Ages in literature, and the beginning of the Early Modern Period.

It was in this context that the modern novel took shape. This form of literature became popular in England beginning in the early eighteenth century with authors such as Daniel Defoe, Henry Fielding, Lawrence Sterne, Johnathan Swift, Horace Walpole, William Congreve and others who wrote in various subgenres—picaresque, Gothic, memoire fiction, and in the epistolary and narrative styles. Female authors became prominent in the early nineteenth century with novels by Jane Austen, George Elliot (born Mary Ann Evans), and Charlotte and Emily Bronte. From there the novel became a major genre in literature.

The modern novel has been described as fictional narrative composed in prose which is the most adaptable of the literary forms, and thus appears on all levels from that of high culture to mass entertainment. Some find little literary value in many novels which they see as middle brow literature and many other novels are regarded as nothing more than cheap entertainment, and thus inconsequential and not worthy of closer attention.

So, one might ask, why bother with it? This question is answered by Joseph Epstein in his latest book The Novel, Who Needs It? His answer is that we all do, “including even people who wouldn’t think of reading novels,” and in this “great age of distraction we may just need it more than ever before.”

Epstein is well qualified to show us why, for he is himself regarded as one of the nation’s leading essayists and critics; a prolific writer, author of thirty-one books, seventeen collections of essays, four books of short stories, and numerous articles which have appeared in publications such as the Claremount Review of Books, Times Literary Supplement, and here in Academic Questions. He has also served as the editor of the American Scholar at what is thought to be that publication’s peak of cultural influence, and taught English for thirty years at Northwestern University. His brief overview of the novel is therefore well grounded and useful for anyone studying this genre at the university.

Epstein describes the novel as consisting of plot, character, action, thought, and often moral themes, and explains that it uses scene, summary, dialogue, description, and point of view in telling a story. Although it is fiction, he says, the novel must above all “produce the successful illusion of reality,” for when a real event is well depicted in a fictional account, readers can experience it in a way they could never otherwise have. For Epstein, reading great novels broadens our experience by allowing us to enter other peoples’ lives, to sense their emotions, and to see how people act in different circumstances. The novel also stimulates the imagination by presenting imagined worlds and possible futures, giving one greater insight into events and persons.

Epstein uses Tolstoy’s War and Peace as an example of an author’s genius allowing the reader to enter a battle scene in ways no non-fictional historical account from the Napoleonic period can do. He explains that various subgenera of the novel—the Roman de clef, historical fiction, Bildungsroman, the coming of age and adventure novel, and others—bring to life different ranges of experience. Serious novels such as Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, and Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, did more to damage Communism than any polemic or firsthand description of totalitarianism. The novel can expose false visions.

Epstein asks “how did this extraordinary form, the novel, come into being?” In answering this question, and following Ian Watt’s The Rise of the Novel, he briefly discusses the novel’s origin by looking back at its predecessors, the epic, the lyric, and the staged drama, all of which survived for centuries without the printing press. Epstein points to industrialization and the rising middle class as key components in this process, as well as to the leisure time in which many people had to read such “hefty tomes” as Don Quixote, Clarissa, Tom Jones.

But the history of the novel, he says, is not like that of science where one advance is built on earlier achievements. It is rather marked by high and low periods as seen in the Russian authors of the nineteenth century, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Goncharov, Leskov, and Chekov (who was more a writer of short stories than a novelist). In England there was the Victorian Period with Dickens, Thackery, George Eliot, Anthony Trollope, and the Brontes, and in the twentieth century Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Power, Kingsley Aims and others. Epstein cites James Fenimore Cooper as the earliest novelist in the nineteenth century high point in the United States, which included Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville among others, followed in the twentieth century by Theodore Dreiser, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Willa Cather. No one can explain those peaks, he says, except that certain talents happened to emerge around the same time.

Epstein also discusses the different ways of reading and judging novels and the difference between great and lesser novels, as well as the nature of the literary canon, citing such literary scholars as Q. D. Leavis (Fiction and the Reading Public 1939), Northrop Frye (The Anatomy of Criticism 2000), F. R. Leavis (The Great Tradition 1972), Georg Lukacs (The Theory of the Novel 1974), Percy Lubbock (The Craft of Fiction 2015), Mikhail Bakhtin (The Dialogic Imagination 1981) and others.

It is Epstein’s belief that by learning to see how authors use language as the medium of their art, we sharpen our own analytic skills and, we might add, it can inspire students to write stories of their own.

Novels are important because one acquires knowledge through them that is different from the kind of knowledge which can be enumerated and subjected to strict testing such as one gets from history, biography, science, criticism, and scholarship in general. The novel is not subjected to those restrictions of empirical measurement, but is wider, deeper, less confining, as it deals with “human existence itself.” For these reasons reading great novels comports well with the kind of liberal education as he conceives it, and that is why it is a genre suitable for inclusion in the liberal arts curriculum in the university.

Neutering the Novel

But all is not well with the novel today. Traditionally the great novelist was free to imagine the lives of other people at any time. As examples Epstein gives us what he describes as two of the greatest female characters in literature, Anna Karenina and Natashia Rostova, both imagined by Leo Tolstoy. But, he says, under the strictures of political correctness this is no longer allowed, for the meaning of the word “appropriation” has been extended “to writing about things outside one’s own gender or ethnicity or even milieu,” so that both the writer’s “imagination and expression have been severely curtailed.” In today’s “climate of fear,” he says, an author dares not cross the line by imagining what someone on the other side might be like, or how they might feel and act, as seen in the treatment of the well-known author of the young adult Harry Potter novels. Thus, political correctness has resulted in making “large segments of the culture no longer open to honest discussion.”

Epstein does not address the issue of the rapid changes that higher education has experienced in recent years; changes which are transforming universities from institutions of learning to centers of indoctrination. He does, however, address the temperament of many students today who have been conditioned by the dominant ideology, and as a result are sensitive to what has been termed “hurtful words” and images. Epstein believes that practices in educational institutions from K-12 to universities have begun to resemble more and more “therapy sessions” with “college students openly declaring themselves feeling unsafe in the presence of ideas with which they disagree, and professors accede to their fears by providing trigger-warnings or simply agreeing not to touch on subjects that might upset them.”

As moveable type and the publishing industry set in motion the development which led to the novel, so too the electronic age—including television and streaming—has the capacity to change reading habits, and as a result the kind of fiction which will be produced. After all, the internet is now handily available via the tablet and the “smart” phone, a device which is carried everywhere in the pocket or the purse.

One aspect of this new technology is the shortened attention span, what Epstein sees as the “reigning side effect of digital culture,” so that lengthy novels will no longer be read. This is quite unlike earlier pre-digital times when the length of a novel was no obstacle, helping as it did fill the time between the monotonous, sometimes brutal tasks of the daily work routine. Perhaps for some readers the longer the novel the better, for that was a time when readers came from their day’s activities for supper and conversations with the family, then, with few other sedentary activities on offer, settled down to read. Some no doubt dreaded the end of a good story.

Epstein also says that reading from screens rather than from the printed page, along with the shorter attention span, emphasizes the bare statement of fact rather than focusing on how facts can be presented in different ways for different effects. But as we’ve seen, bare facts are enhanced and brought to life in narratives. All this may have implications for the writing of fiction in the future. Changes in this sense have just begun and we don’t know where they will lead. But we can imagine one day in the future when the modern novel will be regarded in literature courses as today we regard the epic, the medieval romance, and the narrative poem.

In sum, Epstein’s extended essay is a useful overview of the genre, especially for students, as it introduces them to the names of authors and critics within a broad context, and it shows why the study of the novel remains a valuable part of any serious university general studies curriculum.

Glynn Custred is professor emeritus of anthropology at California State University, East Bay; [email protected]. Professor Custred is the author of A History of Anthropology as a Holistic Science (2016) and last appeared in our pages in the summer of 2023 with “The Forge of War,” a review of Peter Stansky’s The Socialist Patriot: George Orwell and War (Stanford University Press, 2023).

1 Edward Sapir, Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech (New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1949), 222.