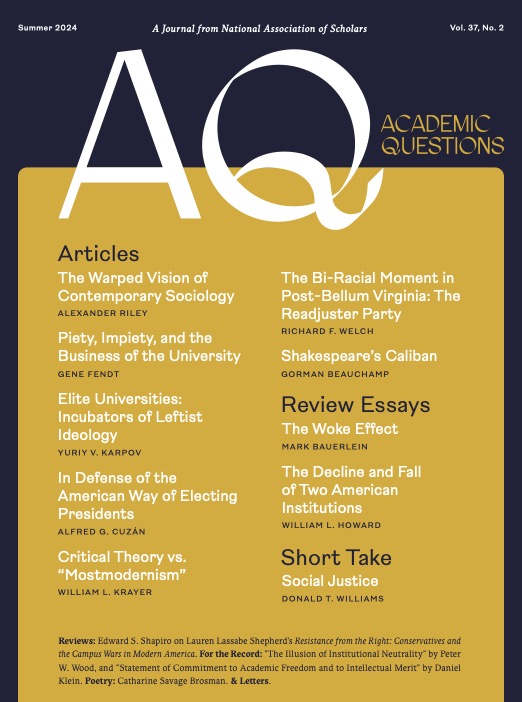

Resistance from the Right: Conservatives and the Campus Wars in Modern America, Lauren Lassabe Shepherd, University of North Carolina Press, 2023, pp. xiv + 260, $99.00 hardcover, $29.95 softcover, $22.99 e-book.

The publication of Lauren Shepherd’s Resistance from the Right in August 2023, coming just a few weeks before the Hamas incursion into Israel on October 7 and the resulting bloody conflict in Gaza, could not have been at a more opportune time. I began reading it on December 9, 2023, the very day that the president of the University of Pennsylvania resigned due to her ham-fisted and rehearsed response when asked at a Congressional hearing whether calls for genocide directed at Jewish students should be tolerated on campus. On January 2, 2024, Claudine Gay, Harvard’s president, was also forced to resign because of her identical answer to the same question, along with subsequent plagiarism charges against her and assorted complaints from various sources about campus policies she instituted.

This is, of course, not the first time that the state of the American university had been a matter of serious public concern. Things were arguably worse and more controversial during the 1960s when protests over the Vietnam War and racism brought several universities almost to their knees and adversely affected scholarship, particularly in the humanities and social sciences. Here, as in 2023, these threats came primarily from the Left, and not surprisingly the rise and fall of the campus New Left has been of major interest of historians, most of whom have been sympathetic to the various protests and protesters.

Resistence from the Right is the latest effort to examine the other side of the campus story of the 1960s, particularly the years 1967 to 1970. It is a revision of Shepherd’s doctoral dissertation at the University of Southern Mississippi, and it focuses on what she perceives to have been the more dangerous threat to academic freedom and scholarship fomented by right-wing students, intellectuals, donors, and politicians. The book is a prime example of “usable past” historiography in which the contemporary concern with race, gender, identity, and left-wing politics provide the context for understanding American history. Other prominent examples of this genre are Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States (1980, 2009) and the 1619 Project of the New York Times.

Shepherd’s understanding of conservatism during the 1960s and the conservative presence on the campus is idiosyncratic, to put it mildly. Her campus conservatives were racists, homophobes, and anti-feminists who sought, above all else, “to preserve a traditionalist racial hierarchy” and opposed “social habits that too closely resembled collectivism and moral relativism.” (26) Her campus conservatives include David Duke, a Louisiana State University student and future pro-Nazi provocateur, in her list of future conservative leaders who came politically of age during the decade. Duke was many things, but he certainly was not a conservative, nor is fascism a conservative movement.

Mussolini and Hitler did not wish to conserve social, political, and economic institutions but to destroy them. But for Shepherd, Duke and his ilk and such violent white supremacist and neo-Nazi organizations as the Minute Men, the White Youth Alliance, Youth for Wallace, the National Youth Alliance, and the National Socialist White People’s Party as well as racist academicians such as William Luther Pierce and Revilo Oliver belong squarely within the campus conservative orbit because they resisted the “victimization of white Christian traditionalist students by atheist, Black, and Jewish left-wing revolutionaries” and supported “reactionary pro-war and anti-civil rights impulses.” (11)

But these organizations, as Shepherd also admits, were not very popular. The Minute Men, for example, a Nazi paramilitary organization at the University of Minnesota, had only eight members.

Nevertheless, Shepherd devotes an entire chapter (chapter 6, “The Black Studies Thing”) to the racism within the campus conservative movement. During the 1960s when courses in Black Studies became something of a rage, prominent academic figures questioned their academic quality and feared they were being taught by political provocateurs and not competent professors. One example was a proposed course on “social analysis” to be taught at the University of California by Eldridge Cleaver who was slated to go on trial for murder. Shepherd dismisses the legitimacy of such concerns and argues instead that they were motivated by racism. For campus conservatives, she asserts, “the cost of educational and civil equality was simply too high, as it came at the expensed of white students’ peace and safety.” While not all conservative white students were blatant racists, “certainly implicit bias, microaggressions, and a reflexive defense of institutional racism were characteristic of the Right and white college students generally.” (120, 129) How could anyone possibly know this?

The efforts of white Christian campus conservatives to preserve racial segregation and white supremacy and their opposition to racial justice is a theme which runs throughout the book. Thus, Shepherd emphasizes the presence of the Confederate flag and the singing of “Dixie” at pro-Vietnam War student rallies in the South “because racial justice and peace were entangled in their minds as liberal goals to resist.” (59) This focus on the issue of civil rights perhaps explains why Resistance from the Right says little about the contribution of other ethnic and racial groups to campus conservatism when compared to its extensive discussion of white male southerners. There is no mention in the book of the role of Jews within the conservative student movement during the 1960s, female conservatives are largely ignored, and less than a page is devoted to black conservative students, many of whom were devout Christians and potentially sympathetic to aspects of the conservative message.

For Shepherd the other great failing of the campus conservatives of the 1960s was their support for the war in Vietnam. These “privileged conservatives,” she notes, “rallied for the war cause from the safety and comfort of their classrooms, thousands of miles removed from the battleground of Vietnam, where less educated, less wealthy, and less white service-members risked life and limb.” (153-54)

simplifies the complex history of the 1960s into a conflict between a righteous Left and a reactionary Right. This division was a major theme of American historiography of the twentieth century beginning with Frederick Jackson Turner, Vernon L. Parrington, and Charles A. Beard, the most prominent historians of the Progressive Era, and continued through their liberal successors such as Henry S. Commager and Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. Simplistic binaries, however, have been unable to portray the complex history of a large, diverse, and dynamic democracy in which there were literally thousands of political factions, and this is particularly true when it comes to discussing dissenters from liberal orthodoxy.

They viewed themselves as members of a beleaguered intellectual movement opposing a left-wing political and cultural establishment which had been dominant since the 1930s. Their battleground was the classroom from which they believed emanated the malevolent ideas contaminating America. The campus conservatives were aided by benefactors such as Henry Salvatori, Joseph Coors, Henry Regnery, and Richard Mellon Scaife, and by foundations and organizations such as the William Volker Fund, the Relm Foundation, the Earhart Foundation, the Lilly Foundation, the Foundation for Economic Education, the Liberty Fund, the American Enterprise, the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, and Young Americans for Freedom. These organizations endowed academic positions, funded scholarships for aspiring conservative scholars, encouraged the research of conservative scholars, and provided literature in order to spread the conservative gospel on campus. These were legal and legitimate activities and were not, contrary to Shepherd, elements of a vast and sinister right-wing conspiracy to subvert academic freedom and oppose efforts at economic and social change.

Conservatives believed the university had deviated from its traditional role and, like a wayward child, needed correction. Leftists, by contrast, viewed American universities as an integral part of a malignant racist-capitalist-imperialist establishment and should be transformed into institutions fostering radical social and economic change. Dispassionate scholarship, intellectual distinction, and academic freedom, they believed, were simply fetishes designed to bolster the political and economic status quo.

Shepherd believes the conservative scholarship of the post-war years was simply window-dressing for reactionaries who wished to return America back to an era when blacks and other minorities knew their place, wealthy businessmen controlled the economy, women were in the kitchen, and “plutocratic white Christians dominated the educational, political, and cultural spheres.” She laments the fact that the young conservatives of the 1960s used the skills they had learned in campus politics to defend the privileged position of the economic establishment, undermine democracy, oppose the New Left and Black Power movements, and “consciously drive American politics and culture further to the authoritarian right, with the Republican party as their vehicle.” (3-4)

Shepherd’s interest is rather on the inflammatory individuals who claimed to be conservative, including members of the John Birch Society, George Wallace, and other denizens of the extremist politics of the 1960s. Her book, in other words, is sizzle without the steak. Better guides to the influence that conservatism had on the campus during the 1960s are George H. Nash’s comprehensive The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945 (1976) and Matthew Continetti’s engrossing The Right: The Hundred Year War for American Conservatism (2022).

Another problem with Resistance from the Right is its distorted view of America during the 1960s. Shepherd claims that the conservatives on campus opposed democracy because they were outnumbered by those protesting the Vietnam War, racial inequities, and other American failings. Conservative students, she says, “discovered that they needed only to appear popular . . . while relying on external powers to uphold structures that privileged them.” They were not part of “an organic youth endeavor” but rather pawns of right-wing philanthropists and a host of “prominent white male writers, politicians, evangelical leaders, segregationists, and anticommunist conspiracists.” (5-6)

But Shepherd doesn’t acknowledge that campus radicals weren’t a majority either. Most college students during the 1960s did not identify as conservatives, liberals, or radicals. As Shepherd notes, “most students were moderate, if they cared for politics at all,” and the majority of campuses were relatively quiet. (187) The most highly publicized protests took place at Ivy League schools, highly selective private liberal arts colleges, and public flagship universities such as the University of California, the University of Michigan, and the University of Wisconsin. This is true as well regarding the protests and riots resulting from the recent war in Gaza. Then as now approximately half of American college students were enrolled in junior colleges, and the major priority for most students was not politics but career advancement, romance, and sport. I taught at St. John’s University, a liberal arts college in central Minnesota, during these years, and the atmosphere there bore little resemblance to what was then taking place in Cambridge, Massachusetts or Madison, Wisconsin.

If anything could be considered a national referendum on the Left of the 1960s it was the 1972 election in which Richard Nixon, the incumbent, decisively defeated George McGovern, the most left-wing candidate nominated by any major American political party during the twentieth century. McGovern won only 37.5 percent of the vote compared to Nixon’s 60.7 percent, carried only the state of Massachusetts and the District of Columbia, and won eighteen million fewer votes than Nixon.

The last chapter in Resistance from the Right contains a brief and rather idiosyncratic history of campus conservatism since the 1960s. Shepherd omits the most crucial aspect of the history of campus conservatism of the period: the coming of age of an inclusive and distinguished conservative intellectual presence on campus. Whether in history, sociology, economics, and other academic disciplines, prominent conservative professors were effectively challenging the regnant left-wing orthodoxy. Shepherd is oblivious to this, and her book ignores the individuals, books, magazines, and ideas which were at the center of the campus conservative movement of the 1960s.

Left unmentioned are the journalists William Henry Chamberlain and John Chamberlain, the economists George Stigler and Frank H. Knight, the sociologists Edward C. Banfield and Robert A. Nisbet, the political scientists Harry B. Jaffa, Francis G. Wilson, and Walter Berns, the political thinker Leo Strauss, the historians Peter Viereck, Gertrude Himmelfarb, and Daniel J. Boorstin, the religion scholar Will Herberg, the philosophers James Burnham and Sidney Hook, and important right-leaning magazines such as Commentary and the Public Interest.

Shepherd instead emphasizes the campus conservatives’ “objection to social change and a desire to retaliate against anyone who questioned the status quo,” as well as a growing “penchant for violence and a fascination with authoritarianism from politicians and administrators in the name of freedom.” (188) This, she claims, helps explains the devolution of American conservatism and the Republican Party into an anti-intellectual cult “engaging in culture wars, amplifying white supremacists, and promoting specious tropes rather than debating substantive ideas.” (193) This culminated, she says, in the attempted take-over of the United States Capitol on January 6, 2021 by white nationalists emboldened by right-wing propaganda.

Perhaps the most bizarre of Shepherd’s arguments is her claim that the rightwing activists of the 1960s, who would later become university trustees, administrators, donors, and state and local politicians, have ended up controlling American higher education. “Conservatives’ ability to gain power over the academy, implement the Right’s favored restraints, and punish those who threaten their minoritarian capacity,” she writes, “is not a recent phenomenon but part of a longer iterative process. The right has developed, refined, and expanded these strategies through sixty years of practice.” (10) This has intensified the “racism, sexism, ableism, classism, homophobia, and xenophobia” permeating the modern American university which, in turn, has been bolstered by a judiciary more interested in upholding the educational status quo than in rectifying racial discrimination. As a result, Shepherd writes, the “systemic legacies of white supremacy in the academy, which have been upheld through conservative counter-efforts at every level of policy-and lawmaking” remain in place. (195-97)

Asian-Americans who challenged the admission policies of Harvard and the University of North Carolina will be surprised to learn that they did so in defense of white supremacy. And conservative academicians will be astounded by Shepherd’s claim that the major victims of censorship on the contemporary campus have been left-wing scholars.

Shepherd is part of what must be a very small minority who believe the Right controls the modern campus and that it has been conservatives who have “thrown sand into the gears of the machines that drive the academy’s democratic missions, then and now.”

This is bad history. No attempt is made to reconcile her view that the Right controls the universities with data showing the ratio of liberals to conservatives in the American professoriate has been at least 5 to 1 since 2000 and for college administrators it is an astonishing 12 to 1.1 The current ills of the American university have not resulted from its capture by conservatives infused with the campus conservatism of the 1960s. Rather, the modern American university, particularly the elite campus, is run by individuals who were influenced by the educational panaceas of the Left during the latter half of the twentieth century and who have imposed the Diversity-Equity-Inclusion regime on the American campus.

For decades organizations such as the American Council of Trustees and Alumni and the National Association of Scholars had been sounding the alarm regarding the state of the American academy, seemingly to little avail. Example number one is Harvard, America’s most distinguished university. The latest survey of the Foundation of Individual Rights and Expression on the status of intellectual freedom within America’s most prestigious universities and colleges ranked Harvard dead last and the University of Pennsylvania second to last. In the fall of 2023 Harvard College experienced a sharp decline in applications for its freshmen class. This occurred while wealthy alumni were holding back their financial support because of the politicization of the campus, the influence of DEI bureaucrats, grade inflation, plagiarism, and the censoring of professors who dissented from the reigning intellectual orthodoxies. The situation has been so bad at Harvard that several professors formed the Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard in order to encourage “free inquiry, intellectual diversity, and civil discourse at America’s oldest university.”

A particularly egregious example at Harvard of academic malfeasance was the treatment of the biologist Carole Hooven. She fell victim to the university’s DEI bureaucracy in 2021 after questioning the fluidity of gender identity on a Fox News appearance and for defending the traditional biological definition of male and female. “Harvard’s culture of intolerance—particularly toward my scientific views on the nature of sex,” she wrote, “led me to feel that my only choice was to leave…. The message is that what matters most, certainly above the search for truth, is how people’s words affect groups deemed ‘marginalized.’” Harvard, she concluded, “has a long way to go to restore an environment where those on its campus feel free to teach, write, and speak without fear.”2 Ironically, Harvard’s motto is “Veritas” (truth).

Edward S. Shapiro is professor emeritus of history at Seton Hall University; [email protected]. He is the author of A Time for Healing: American Jewry Since World War II (1992), Crown Heights: Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Riot (2006), A Unique People in a Unique Land: Essays on American Jewish History (2022), and the editor of Letters of Sidney Hook: Democracy, Communism and the Cold War (1995). Shapiro last appeared in AQ with “Remembering Harvard” (Winter 2023).

1 Samuel J. Abrams, “Think Professors Are Liberal? Try School Administrators,” New York Times, October 16, 2018.

2Carole Hooven, “Why I Left Harvard,” The Free Press (online), January 17, 2024.

Photo by Unseen Histories on Unsplash