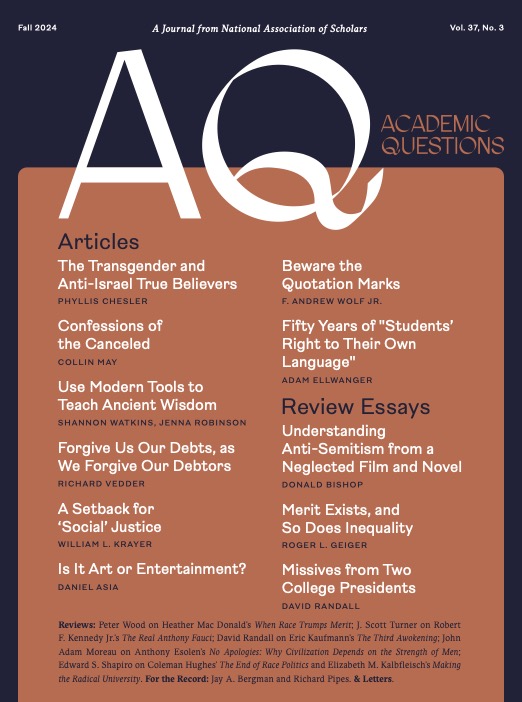

The End of Race Politics: Argument for a Colorblind America, Coleman Hughes, Random House, 2024, pp. xviii + 235, $30.00 hardcover.

Coleman Hughes bears watching. He is currently a fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute for Policy Research and a contributing editor of its City Journal. He appeared on Forbes’ 2021 list of outstanding young Americans under 30 years of age, and has written for the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, National Review, the Spectator, and other publications. The End of Race Politics is his first book.

The volume is a persuasive and compelling counter to the New York Times’s 1619 Project, intersectionality, affirmative action, Critical Race Theory (CRT), racial preferences, wokeism, calls for reparations, and the cult of victimhood which have plagued American society, particularly our universities, now for several decades. America’s elite universities, Abe Greenwald recently noted in Commentary, now resemble fun-house mirrors “in which racists are reflected back as angels, colorblindness as racism, one sex as the other, democracy as tyranny, tyranny as paradise, freedom as bondage, refugees as colonialists, Jews as white oppressors, and terrorists as saints.” But it was only during the campus protests over the war in Gaza that Americans became fully aware of the carnage which academia has suffered and of “the full catalogue of grotesquery that is American higher education.”1

Just as the country owes a debt to the black voters in South Carolina who sidetracked the presidential candidacy of Bernie Sanders in 2020, so should it acknowledge the role that black academicians such as Glenn C. Loury, John McWhorter, Thomas Sowell, Wilfred Reilly, and now Coleman Hughes have played in defending America and the principles of racial equality and merit against the assaults of the bien pensant in the academy.

There is nothing startlingly new in The End of Race Politics, but in instances such as these, stating the obvious and puncturing illusions is far more important. Discussions of race on the contemporary campus resembles an inverted form of Marxism propagated by “neoracists” (Hughes’s term) in which society is divided not into classes but into races, with the white race being the perpetual oppressor and the black race the eternally oppressed. Since critical race theorists claim that racism has been the magical key to understanding American history since 1619, it is simply impossible for its exponents, including Nikole Hannah-Jones, Robin DiAngelo, Ibram X. Kendi, and Ta-Nehisi Coates, to view American race relations as an evolving phenomenon with a distinctive history.

The neoracists are taken seriously both within and beyond the American academy. Thus, Coates’s much hyped and thin Between the World and Me won a National Book Award in 2015, and in that same year he also received a “genius award” from the MacArthur Foundation. DiAngelo’s White Fragility was also well received. In it she declared that the effort to end racism demands that whites cease being white since “to be less white is to be less racially oppressive…. To be less white is to be open to, interested in, and compassionate toward the racial realities of people of color.” Kendi claimed in his book How to Be an Anti-Racist that “ only remedy to racist discrimination is anti-racist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.” Perhaps only in academia would these notions be given serious intellectual deference.

Although American slavery was outlawed shortly after the end of the Civil War, CRT advocates argue that the position of blacks as a subjugated race is frozen in time and has not fundamentally changed over the past one hundred and forty years. This is despite the fact that blacks have recently occupied the highest positions in government and the military, have headed some of its leading universities and corporations, and have been among its most highly paid and admired athletes and entertainers.

Other indicators, such as the intermarriage rate between whites and blacks, the decline in membership in the Ku Klux Klan and other racist organizations, and the ascent of many blacks into the middle class also attest to the changing nature of American race relations. While Martin Luther King, Jr. argued that people should be judged by the content of their character and not the color of their skin, the reigning academic racial indulgence emphasizes the primacy of race.

its title, politics is not the most important or the most interesting focus of The End of Race Politics. Hughes is out for bigger game. The book’s six succinct chapters seek to fundamentally challenge the neoracist and victimization reading of the history of America’s blacks and their contemporary condition, and to validate the integrationist and hopeful approach of King, A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, and other old-school leaders of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The “destructive” and “extreme” ideology of the neoracists, Hughes notes, is “contrary to the spirit of the civil rights movement” and is antagonistic to American values and traditions. “It’s only by perpetuating interracial hatred,” “spreading the myth that our society has made little progress toward eliminating racism against people of color,” and “exaggerating the threat of white supremacy” can the neoracists emerge victorious. An emphasis on “colorblindness,” a buzzword which Hughes frequently uses, is the most effective way to check the neoracists.

Hughes observes that the current obsession with race distorts reality. The U.S. Census category of “Asian-American,” for example, is nonsensical since it includes individuals from Japan, China, India, Pakistan, Korea, and Vietnam who have little in common. But defining them in this way became necessary once race-based social programming became popular. Government officials had to know whom to include as well as whom to exclude in dispensing funds. The same has been true of the category “Hispanic.” Spaniards, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, and Argentinians have little in common except for language. Brazilians are considered Hispanics by government officials even though they speak Portuguese. I know of a high school senior whose parents were wealthy white immigrants from South Africa. He claimed on an application to an Ivy League college to be “Afro-American.” His ancestors did in fact come from Africa, and he had grown up in America: hence Afro-American, but not quite the Afro-American his college was looking for.

All of these racial categories, Hughes correctly notes, are arbitrary and unscientific. Somehow it is not politically correct to describe Asian-Americans as “yellow” and Indian-Americans as “red,” but perfectly acceptable and even necessary to talk about “black,” “brown,” and “white” people as if these are scientifically credible racial categories. Unqualified government officials are now authorized to make decisions on these matters which are beyond their ken. Hughes also notes that divisive attempts to categorize immigrants and ethnics have been unpopular among their supposed beneficiaries. The term “Latinx,” for example, is rejected by most Spanish-speaking immigrants and their descendants for whom it was designed.

Neoracist policies are also unpopular among its supposed beneficiaries. One example is the disastrous attempt to defund the police which is particularly unwelcome within black majority communities afflicted with high crime rates.

Hughes believes that neoracism is responsible for much of the anger which currently permeates American politics. Beginning in the 1960s when neoracist policies were first instituted, individuals have been penalized for being members of an unfavored race or ethnic group. This has inevitably led to widespread outrage by the victims of this bias. “It is unreasonable to expect people of any race to sit idly by as laws get passed that openly discriminate against them on the basis of race,” Hughes notes, and this is particularly true in a nation whose founding document declares that all men are created equal.

Unfortunately, Hughes writes, neoracist ideology “has found a comfortable home in higher education,” seen for example in segregated dormitories, discriminatory student admission policies, and racially separate study programs and graduation ceremonies. All of these run counter to the educational mission of colleges to expose students to cultures, ideas, and viewpoints different than their own and, to quote Hughes, “artificially restricts their experiences of the world in a way that is contrary to the goals of higher education.”

Supreme Court decision of June 2023 in Students for Fair Admissions Inc. v. University of North Carolina, et al., which struck down the race-conscious admission policies at Harvard and the University of North Carolina, was a step in the right direction. response of university administrators indicates, however, that they will do everything in their power to deflect the court’s conclusions.

What should be done to counter the nefarious influence of neoracism? Here Hughes pulls no punches. It is impossible, he says, “to avoid the unfair policies that result from using arbitrary racial distinctions to dole out social advantages or disadvantages. The way to avoid this kind of unfairness isn’t to come up with different race categories; it’s to get out of the business of racial classification altogether.” It is necessary to recognize that black racists preaching Critical Race Theory are no better than white racists since both groups renounce our common humanity, reject racial equality, and deny that everyone should be treated equally. The neoracism of DiAngelo and Kendi, Hughes concludes, “is the latest form of bigotry that American society has failed to stigmatize sufficiently. It’s the latest form of socially approved bigotry.”

Hughes's goal of a colorblind society that rejects racial stereotypes and divisions and embraces our common humanity will, however, be opposed by the race hustlers, diversity bureaucrats, media figures, academicians, politicos, and various onlookers who benefit, both financially and status-wise, from neoracism.

This colorblindness came naturally to Hughes. He was born in 1996 and raised by an African American father and a Puerto Rican mother, neither of whom were fixated on race. Nor was race a major issue for Hughes while growing up in integrated and affluent Montclair, New Jersey or while attending Newark Academy in Livingston, New Jersey. It was not until he entered Columbia University, where he majored in philosophy, did he encounter neoracist classmates, professors, and academic administrators who rejected the goal of a colorblind society and considered the question of race to be of paramount importance. Hughes survived Columbia and is convinced that an obsession with race is a dead-end for blacks and “irrelevant to the things we care most about in life.”

He treasures instead the dissent of Justice John Marshall Harlan in the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision of 1896 which allowed for racial segregation in schools. Harlan claimed, “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. The humblest is the peer of the most powerful.” Equally important to Hughes is Martin Luther King’s belief that

black supremacy is as dangerous as white supremacy, and God is not interested merely in the freedom of black men and brown men and yellow men. God is interested in the freedom of the whole human race.

Hughes concludes his book with an eloquent defense of colorblindness. “We need to seize the current opportunity to recommit ourselves to the principles of the civil rights movement,” he says. “We need to condemn neoracism for what it is: racism in anti-racist clothing. . . . We need to embrace our common humanity and the colorblind philosophy that follows from it.” Hughes is certainly correct, and perhaps his next book will show in greater detail how this can be done.

Edward S. Shapiro is professor emeritus of history at Seton Hall University; edshapiro07052@yahoo.com. He is the author of A Time for Healing: American Jewry Since World War II (1992), Crown Heights: Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Riot (2006), A Unique People in a Unique Land: Essays on American Jewish History (2022), and the editor of Letters of Sidney Hook: Democracy, Communism and the Cold War (1995). Shapiro’s “The Academy and Its Discontents,” a review of Elizabeth M. Kalbfleisch’s Making the Radical University: Identity and Politics on the American College Campus also appears in this issue.

1 Abe Greenwald, “The Woke Jihad,” Commentary, 157 (June 2024), 24.

Photo by Deagreez on Adobe Stock