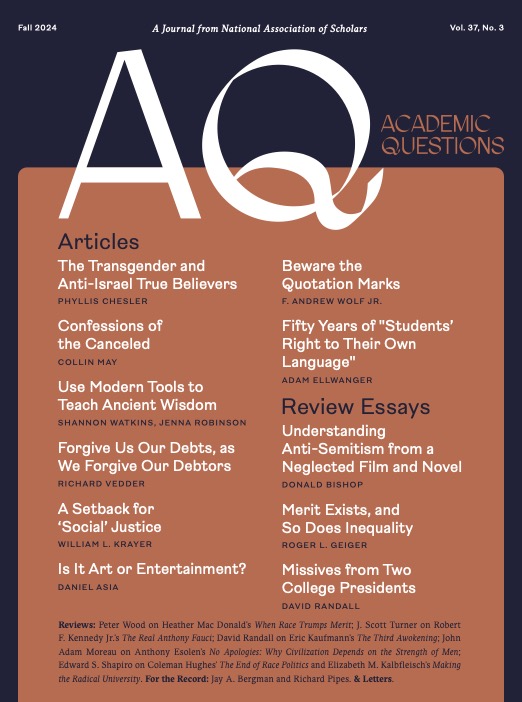

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the greatest shift that ever unfolded in writing pedagogy. In 1974, the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC), a professional organization for writing professors that is affiliated with the National Council of Teachers of English, enacted a resolution entitled “Students’ Right to Their Own Language” (SRTOL).1

That resolution is worth quoting in full:

We [members of CCCC] affirm the students' right to their own patterns and varieties of language—the dialects of their nurture or whatever dialects in which they find their own identity and style. Language scholars long ago denied that the myth of a standard American dialect has any validity. The claim that any one dialect is unacceptable amounts to an attempt of one social group to exert its dominance over another. Such a claim leads to false advice for speakers and writers, and immoral advice for humans. A nation proud of its diverse heritage and its cultural and racial variety will preserve its heritage of dialects. We affirm strongly that teachers must have the experiences and training that will enable them to respect diversity and uphold the right of students to their own language.

Stripped of the high-handed moralism and self-serving rhetoric, this statement announced that English professors were done requiring that students observe the conventions of what they call “Standard Written English” (SWE). They would no longer teach by the paradigm that they derisively called “current traditional rhetoric.”2

Although “current-traditional” methods had been used to train writers for centuries, the cultural revolutionaries of the 1960s and 1970s rejected it, alleging that it made a fetish of grammatical correctness, overvalued propositional and logical coherence, and focused too much on the quality of students’ writing.3 According to the experts at CCCC, those stuffy old expectations unfairly penalized students who came from backgrounds in which they don’t use SWE. Not only that—they argued the traditional approach to teaching composition actually hindered students in learning to write.

In the years after 1974, the overwhelming majority of college writing teachers would elevate the composition process over the actual writing that students produced. This approach came to be called “process pedagogy,” which was a teaching method that eventually developed as a response to the sentiments expressed in SRTOL. After all, SRTOL did not offer pedagogical strategies—it was just an expression of moral sentiment. Its proponents insisted that standards related to spelling, grammar, syntax, voice, and argumentation were just tools for maintaining the purportedly unjust sociopolitical power that accrues to SWE. Teachers committed to SRTOL and process pedagogy preached the idea that all English dialects were equally valid and useful vehicles for written communication in professional and academic settings. This vibrant new perspective, they assured us, would not only produce better student writers—it would move us towards social justice by challenging what they said were the artificial and arbitrary norms of white, bourgeois discourse.

When the 1974 announcement of the resolution was published in the organization’s journal titled CCC, it was accompanied by its underlying rationale, which claimed that as “submerged minorities [insisted] on a greater share in American society,” college English departments were faced with unique challenges.4 The architects of SRTOL could have justified the resolution simply on these moral and political grounds, arguing that it was the right thing to do. But they went further. They claimed that by deemphasizing traditional standards and conventions in the evaluation of student writing, SRTOL would produce better writers. But fifty years have now passed during which SRTOL and process pedagogy were indubitably the dominant approaches to teaching writing. So, have they fulfilled their promise?

English professors are not the best people to answer this question because they are unique in that most of them see “good writing” as confessional writing about the self—ideally, writing related to themes that affirm the worldview of the political left.5 But among history and biology professors and among employers and recreational readers, correctness and clarity remain the markers of good writing. It is virtually uncontested that as SRTOL became dominant, the quality of student writing, on the whole, became entirely inadequate for both serious academic inquiry and the communication needs of an advanced society.

In what follows, I examine the many “myths” about Standard Written English that SRTOL advocates claim they have debunked. These supposedly false assumptions of “current traditional rhetoric” were touted as the reason a new paradigm was needed for teaching writing. But what if the “myths” that SRTOL enthusiasts used to discredit the traditional approach aren’t myths at all? What if they are true? If so, then it would show that the case for SRTOL was built on sand. That revelation, combined with the obvious decline in student writing over the last fifty years, might be enough to embolden some scholars (inside and outside English departments) to challenge this radical paradigm—one which was genuinely novel during the twentieth century cultural revolution, but has since hardened into the dreaded “status quo.”

“Myth” 1: There is a Standard Variety of American English

The SRTOL resolution explicitly says “Language scholars long ago denied that the myth of a standard American dialect has any validity.” This statement is not easily verified because in the official justification of SRTOL, the authors deliberately avoid backing up their claims with in-text citations. Instead, they tack on a bibliography of dozens of scholarly sources that supposedly verify the claims of the resolution at large. In short, the authors took pains to make it difficult for readers to verify their arguments. Most instructors simply took their word for it.

CCCC tries to convince readers by lamenting that so many teachers have made the mistake of believing that “somewhere a single American ‘standard English’ … could be isolated, identified, and accurately defined.” But has anyone ever really said that? This is a straw man—the authors are playing rhetorical games. Simply because the Platonic ideal of the American hamburger cannot actually be found out in the world doesn’t mean that there isn’t a basic conception that the general public shares about what that hamburger would be like. It would be the most common, typical, basic hamburger that you encounter (albeit with minor variations) in the local diner of any town in the United States.

Standard American English is the same. You will never run into a single person who speaks the living embodiment of standard American English. But there is most certainly an identifiable way that the American majority speak the language. Everyone’s speech deviates from the standard to some degree, but not all to the same degree—and some deviations are more significant than others. Most Americans don’t notice when someone uses the word less when fewer is the correct one, and most listeners won’t catch when someone confuses rightly with rightfully. But most Americans will note when an adult native speaker pronounces ask as “acks” or when someone says “lie-berry” when they mean library. SRTOL advocates would argue that an error is an error, and there are no justifiable distinctions between “minor” and “major” errors.

Again, this is pure fantasy. A minor error is one that is commonly made by many speakers. A major error is one that is comparatively less common. People tend to notice major errors more than minor ones, and committing major language errors has implications for how audiences respond to speech. None of this is meant to denigrate people who speak language varieties that differ from the standard. It’s just to admit the obvious: there are many similarities in how legacy American citizens speak. Those similarities even extend to common errors of usage and pronunciation. These similarities are especially evident among Americans who have received quality secondary education or beyond. To pretend that these things aren’t the case is childish.

“Myth” 2: You Can Change Language Habits Learned Early in Life

The CCCC’s experts assure us that “sophisticated research” has “demonstrated incontrovertibly that many long held and passionately cherished notions about language are misleading at best, and often completely erroneous.” Again, they don’t specify which sophisticated research debunks each of the myths that we cling to when it comes to writing and language. Instead, they explain there is no research that indicates that dialects and habits “acquired so early in life … can consciously be changed.” Simply put, CCCC claims that if someone grows up in a home where non-standard dialect is spoken (a mysterious scenario since they say no standard dialect exists), then it is impossible for this person to develop competence in a dialect other than the one they learned first.

How do we know that speakers of other dialects can’t learn a new one? According to CCCC, it’s because there isn’t research that proves they can. But do we really need scholarly research to validate this?6

Does anyone doubt that the soaring Ciceronian oratory that Frederick Douglass delivered in perfectly grammatical American English was not the dialect that he first learned in the slave houses of his early youth? Neither do we need such a rare example as Douglass. How many people who were the first in their families to attend college eventually became professors who mastered the very convoluted norms that govern academic discourse and scholarly writing?

In short, people learn dialects (and entire languages) other than the ones they spoke at home all the time. Instead of admitting this obvious fact, scholars in composition studies recommend that teachers give up any attempt to equip students with these other dialects, assuring us (without substantiation) that it’s impossible, and thus, a waste of effort.

“Myth” 3: Standard English Has an Inherent Advantage Over Minority Dialects

There are still other “myths” that the CCCC had to debunk before writing teachers all accepted the “truth” that every student has “a right” to his “own” language. For example, they chide those teachers who have taught “as though the ‘English of educated speakers’ … had an inherent advantage over other dialects.” Again, the advocates of SRTOL are playing games. The key word here is “inherent.”

Yes: it’s true that there is no pre-social, pre-historical, pre-cultural reason as to why standard American English is more advantageous than any other American dialect. But in the actual, existing world—the world where society is a thing, where history happened, and where culture matters—there are obvious advantages associated with the mastery of an English dialect that approximates the one held up as the “standard.”

The ability to communicate in the standard dialect signals many things about the person who is speaking or writing. Unquestionably, aptitude in standard English is a class and cultural marker, and as such it corresponds with certain powers, privileges, and advantages. Clearly, the people at CCCC in 1974 understood this: they just thought it was an injustice. Therefore, instead of trying to teach individuals who were less familiar with the standard dialect to use it effectively (thereby helping those people lay claim to a share of that power and privilege), they explicitly refused to teach it. After all, CCCC had already debunked “Myth” 2: they said students wouldn’t be able to learn a new dialect anyway.

“Myth” 4: You Can Teach Standard Written English and Affirm the Culture of Minority Students

The proselytizers of SRTOL suggest that by teaching standard written English to students who don’t presently use it, schools are trying to “erase differences” and instructors “are actually rejecting the students themselves, rejecting them because of their racial, social, and cultural origins.”7

Indeed, it would be a very bad thing if by teaching standard writing conventions and verbal dialects, we were rejecting individuals on the basis of their race and cultural origins. But of course, that’s not at all what is happening. It may look like that’s what’s happening—because (obviously) people who belong to racial and cultural minorities will often speak minority dialects. It shouldn’t surprise us, then, that those groups will often require more instruction in the features of the majority dialect. CCCC ignores the apparently disquieting reality that a majority dialect (i.e., a “standard” dialect) exists because racial and cultural majorities exist.

Thus, it might appear that CCCC is calling for a policy of neutrality in regard to the many dialects that Americans speak. But such a neutrality is not possible. To assert the equal legitimacy and utility of minority dialects is to disfavor the use of the majority dialect in practice—quite the opposite of “neutrality.”

As a result of this deception, the advocates of SRTOL present teachers with a false choice: either instructors teach the conventions of SWE (and thereby reject the humanity of their minority students) or they affirm all dialects as equally valid and useful (affirming their minority students and striking an imaginary blow for social justice).8

There is an alternative: teachers can affirm the dignity of minority dialects while acknowledging the benefits and advantages that come with the mastery of standard English, encouraging students to master it as a way to achieve social mobility.

“Myth” 5: Teaching Standard Written English Can Be a Form of Liberation

The SRTOL resolution itself also chides teachers by reminding them that saying “any one dialect is unacceptable amounts to an attempt of one social group to assert its dominance over another.”9 Personally, I have never heard anyone say that a particular dialect is wholly unacceptable, and certainly never among English professors.

Once again, the CCCC authors are tilting at windmills. Every educated person understands there are different ways of speaking the language. It’s fine for someone to speak one dialect at home, another with friends, and still another at work—most of us do this all the time. Context is the essential factor here. No dialect is ever totally “unacceptable,” but all dialects are unacceptable in certain rhetorical situations. And even then, it isn’t really true that any given way of speaking is unacceptable—it’s more that it is ill-advised for achieving the speaker’s goals.

The scholars at CCCC envision a world where there are no consequences for choosing to disregard the rhetorical expectations of certain audiences. Again, this borders on adolescent delusion. People expect others to conform to established routines for navigating recurrent communicative situations. Refusing to do so will make it harder for you to get what you want—but you always retain the ability to defy those expectations. Choosing defiance (consciously or otherwise) may have consequences. But by no stretch of the imagination can that be called a form of “domination.”

Actual Myth: Students’ Right to Their Own Language

In the interest of space, I have avoided dissecting the many, many other factually-true “myths” that the cheerleaders of SRTOL and process pedagogy have claimed to debunk.10 The point is clear: composition scholars have adopted a theory of teaching that denies fundamental realities about language and communication.

The biggest myth is that refusing to teach students the conventions of standard written English will somehow make them better writers. But a close second is the notion that students have a “right” to their “own” language. Any language is a tool for communication between people. In other words, no one has their “own” language—and if someone does, it doesn’t count as a language because it can’t serve as a medium of communication. The truth is that languages belong to nations and peoples and tribes: to the extent that a language is “owned,” it is always owned communally. Every linguistic community has norms and conventions that are largely determined by the will of the majority. There is no alternative to that. Ultimately, then, no individual has a “right” to their own language because no individual has a language to call their “own.” CCCC’s assertion that individuals can and should exercise sovereignty over the medium of communication isn’t just impossible—it’s dangerous. It creates the perception of individual grievance where none exists, and if the past five years have taught us nothing, they have at least shown us the enormous social costs that extend from imagined grievances.

SRTOL never conveyed any empirical realities about language that would help improve students’ writing—but that was never its aim. Rather, it was an expression of teachers’ political preferences. SRTOL was just a means for activist teachers to give high-minded justifications for not doing what they didn’t want to do. Professors felt good that underprepared students from historically marginalized groups were granted access to the universities, but they were reluctant to fail those students when some proved unable to meet the academic standards that obtained at the time.

Instead of protecting the value of academic credentials, today’s faculty opted to abdicate their responsibilities as teachers. They said standard English is just a fantasy. They silenced skeptical instructors by pretending that SRTOL’s fabulist claims were so manifestly evident that they needed no demonstration. And by insinuating that anyone committed to the old standards was a bigoted know-nothing, they coerced generations of teachers into accepting as reality the many falsehoods on which SRTOL depends.

The resolution ultimately did what it was supposed to do. But it came at a cost: on the whole, today’s students are far less equipped to meet the writing demands of collegiate study. Thus, standards continue to decline in a university context where the pursuit of excellence is discouraged and disdained.

Adam Ellwanger is a professor of English at the University of Houston–Downtown. Ellwanger teaches graduate and undergraduate courses in rhetoric and composition. His latest book is Metanoia: Rhetoric, Authenticity, and the Transformation of the Self (Penn State University Press, 2020). Ellwanger last appeared in AQ in winter 2021 with his article “The Art of Teaching and the End of Wokeness.”

1 “Students’ Right to Their Own Language,” College Composition and Communication. Accessed May 31, 2024. https://prod-ncte-cdn.azureedge.net/nctefiles/groups/cccc/newsrtol.pdf

2 See James A. Berline, Robert P. Inkster, “Current Traditional Rhetoric: Paradigm and Practice,” Freshman English News 8, no. 3 (1980): 1-4, 13-14.

3 See Valerie Felita Kinloch, “Revisiting the Promise of ‘Students’ Right to Their Own Language’: Pedagogical Strategies,” College Composition and Communication (CCC) 57, no .1 (2005): 83-113.

4 The “Explanation of Adoption” can be found at the webpage listed for “Students’ Right to Their Own Language” above (see note 1). The original publication of this document can be found in the special issue of College Composition and Communication (CCC) 25 (1974).

5 See Lester Faigley, “Ideologies of the Self in Writing Evaluation” in Fragments of Rationality: Postmodernity and the Subject of Composition (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992): 111-131.

6 Such research does, of course, exist – at least in recent years. See Lisa Delpit, “The Politics of Teaching Literate Discourse” in Susan Miller (ed.) The Norton Anthology of Composition Studies (New York: WW Norton and Co., 2009): 1311-1321.

7 “Students’ Right to Their Own Language.”

8 For another example, see Mike Rose, “The Language of Exclusion: Writing Instruction at the University,” College English 47, no. 4 (1985): p.341-359.

9 For further evidence of this sentiment, see A. Suresh Canagarajah, “The Place of World Englishes in Composition: Pluralization Continued,” College Composition and Communication (CCC) 57, no. 4 (2006): 586-619.

10 Rose’s essay, cited in FN 8 above, also catalogues a number of “myths” that are unquestionably true.

Photo by Joshua Hoehne on Unsplash