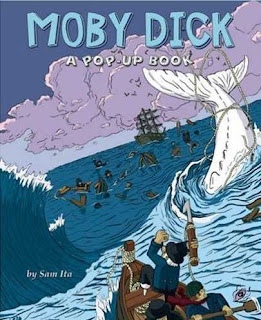

When I came back from the conference and unpacked, the first thing I noticed was the slip from  the Transportation Security Administration in my suitcase informing me that my luggage had won the lottery for random inspection. So the TSA folks got a glimpse of my copies of Raggedy Ann and Andy and the Camel with the Wrinkled Knees, Little Red Riding Hood, and Predators—three additions to my growing collection of pop-up books. (I reviewed the pop-up Moby-Dick in a recent issue of Academic Questions.) I suppose there could be a coded message in those titles, but TSA mercifully left them alone.

the Transportation Security Administration in my suitcase informing me that my luggage had won the lottery for random inspection. So the TSA folks got a glimpse of my copies of Raggedy Ann and Andy and the Camel with the Wrinkled Knees, Little Red Riding Hood, and Predators—three additions to my growing collection of pop-up books. (I reviewed the pop-up Moby-Dick in a recent issue of Academic Questions.) I suppose there could be a coded message in those titles, but TSA mercifully left them alone.

The conference at the University of Virginia was titled, “Who is Called a ‘Parent’ and Why? An Interdisciplinary Investigation of Core Questions at the Heart of Today’s Family Debates.” That much abused word “interdisciplinary” in this instance was meant quite seriously. This was a gathering of some forty scholars, including endocrinologists, primatologists, physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, and professors of law, philosophy, and religious studies. Not only was it interdisciplinary, but rarer still, it crossed a fairly wide spectrum of the cultural divide, including both well-known proponents of gay marriage and other flexible redefinitions of the family, and well-known skeptics.

This was the sort of venture higher education ought to see more of: a robust but civil exchange of ideas, bringing people together who are more often the targets of one another’s polemics than they are partners in dialogue. The dialogue was certainly at times strained, but it didn’t collapse: a victory of etiquette over passion, and perhaps a dividend from the conference organizers’ decision to make this a closed meeting. With no gallery to play to, the participants had only each other.

The event was sponsored by the Institute for American Values in New York, the Center of the American Experiment in Minneapolis, and the Marriage Matters Project at the University of Virginia. Perhaps it says something about American higher education that an event like this arose through the efforts of two independent foundations rather than a university or a scholarly association. One of the prices of ideological orthodoxy on campus is that legitimate discussions that could take place generally don’t unless some external agency like IAV intervenes.

The conference was divided into two sections, one on “What is Parenthood?” the other on “Is Parenthood Gendered?” The former gathered mostly the feminists, legal theorists, social scientists, and humanists. The latter gathered mostly the natural scientists, but the divisions were only approximate. One conferee straightened my collar at breakfast one morning, while another observed, “Grooming behavior. Your prolactin level should rise.” As my prolactin levels rose, I felt suffused with a warm feeling about the natural scientists.

The conference was, to use an old-fashioned term, a disputation. Each speaker was paired with another espousing a more or less contrary view.  Steve Balch, in an essay in The Chronicle of Higher Education, a few years ago suggested that the restoration of the medieval tradition of the disputation might be one of the ways in which the liberal arts could be restored to firmer footing. He called for “rational disputation defined by common rules of intellectual rigor, fairness, and professional respect.” None of this is easily achieved, but the Parenthood Conference came as close as anything I’ve seen. The dispute in this case was between scholars who embrace a social constructivist view of the family and those who embrace a view that the family is, to some extent, founded in natural or biological reality. For the purposes of the debate, the social constructivist side was dubbed the “diversity” position and the natural law side the “integrated” position. That is, the proponents of “diversity” were expected to defend the idea that families—and parenthood—could legitimately take many forms, some of them quite untraditional. The proponents of “integration” were expected to argue that sexual relations, marriage, long-term spousal commitment, and childrearing should generally be part of a single arrangement, and not parceled out separately.

Steve Balch, in an essay in The Chronicle of Higher Education, a few years ago suggested that the restoration of the medieval tradition of the disputation might be one of the ways in which the liberal arts could be restored to firmer footing. He called for “rational disputation defined by common rules of intellectual rigor, fairness, and professional respect.” None of this is easily achieved, but the Parenthood Conference came as close as anything I’ve seen. The dispute in this case was between scholars who embrace a social constructivist view of the family and those who embrace a view that the family is, to some extent, founded in natural or biological reality. For the purposes of the debate, the social constructivist side was dubbed the “diversity” position and the natural law side the “integrated” position. That is, the proponents of “diversity” were expected to defend the idea that families—and parenthood—could legitimately take many forms, some of them quite untraditional. The proponents of “integration” were expected to argue that sexual relations, marriage, long-term spousal commitment, and childrearing should generally be part of a single arrangement, and not parceled out separately.

Inevitably, some on both sides of the debate chafed at the definitions they had been handed. One feminist preferred to call her position “pluralist,” and to label her opponents “universalists.” Several participants saw more of a continuum between the two positions than a dichotomy. Some of the advocates of the “integrated” position ended up in strange places, such as advocating that the biological father of a child born to a married Lesbian couple should be formally considered a party to the marriage. But the contending positions were well enough drawn that a coherent debate really did ensue.

An undergraduate student who is interning at the Institute for American Values was impressed by what he saw. He emailed me that the conference had persuaded him that “more than ever” he wanted to become a scholar because:

I saw how important ideas are and how ideas that I consider essential to human flourishing (e.g. sexual complementarity) are assumed to be discarded relics. A nuanced argument and persuasive rhetoric may not be enough to convince [one of the participants], but surely it does influence the larger cultural dialogue. I couldn’t help but think how the trepidation that I felt in the presence of the liberal feminists wouldn’t be there if they hadn’t been advancing these ideas for decades—and winning arguments in the public square. Now, I certainly wouldn’t ever want my intellectual opponents to feel that sort of trepidation—but I do want them to get the sense of “Wow, this is a serious argument that I must respond to.”

That by itself is a pretty powerful argument for restoring formal “disputation” to the repertoire of ways for scholars to contribute to important public debates.

The particular dispute at this conference has deep roots in the culture of the academy. The arguments against Western norms that favored traditional family structure arose first in my discipline, anthropology, most famously in the fables told by Margaret Mead about the sex lives of Samoan adolescents and the inversion of Western ideas about the correlation of sex (we are now trained to say “gender”) and temperament in various New Guinea tribes. By the 1970s, the feminist critique of the family had successfully overturned the pro-family perspectives in a wide range of disciplines, including psychology and sociology. And academic feminism played a key role in the 1980s in the wholesale abandonment by anthropology of its core sub-discipline, the study of kinship. The movement for gay marriage began in earnest in law journals.

Any attempt to trace the decline of sanctions against out-of-wedlock childbearing, the rise of “alternative” families, and the development of new conceptions of parenthood has to reckon with the power of the academy to make these novelties seem legitimate. The academy is far from the only force driving these changes. The advent of the birth control pill and the avalanche of “assisted reproductive technologies” (ART) have their own teleological effects, as did government policies, such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (1935-1997) which created a strong financial incentive for impoverished women to bear and raise children outside marriage. But even these changes are entwined with the academy. Many of the AR technologies grew out of academic research, and schools of social work gradually came to reject the idea that marriage is the most effective anti-poverty program in favor of maintaining the unwed poor as clients of the state.

The more-or-less settled preference within the academy for expanding adult liberty at the expense of children has been noted by various observers, including David Tubbs, whose important book Freedom’s Orphans (2007) points to the emergence of a fully-articulated ideology within contemporary liberalism. The academy pushes relentlessly for enlarging the sphere of autonomy for adults as sexual actors, while relegating children to a kind of penumbral existence.

We have an issue of Academic Questions coming out in early 2009 on the liberal arts and the family which will take up some of these matters. It includes an interview with the sociologist David Popenoe, whose book twenty years ago, Disturbing the Nest: Family Change and Decline in Modern Societies, challenged the orthodoxy among social scientists that, though the family was changing, it was impervious to actual decline. Popenoe’s new book, War Over the Family, brings the story of family decline in America up to date and offers an account of how we might go about “rebuilding the nest.”

Disputation, important as it is, appears not to stimulate prolactin levels or otherwise induce oceanic feelings of comfort. After two days of pointed exchange with scholars who specialize in denidification, I sought the refuge of imagined childhood. Hence Raggedy Ann and her predatory friends popping up at the TSA inspectors.