Executive Summary

In the last four years, Confucius Institutes have rapidly closed down across the United States. Amid pressure from the FBI, the Department of State, Congress, and state legislatures, colleges and universities have terminated their agreements for these Chinese language and culture centers sponsored by the Chinese government. Of 118 Confucius Institutes that once existed in the United States, 104 have closed or are in the process of doing so.

The demise of Confucius Institutes (CIs), one of China’s most strategic beachheads in American higher education, has not deterred the Chinese government from seeking alternative means of influencing American colleges and universities. It has used an all-of-the-above approach to protecting its spheres of influence on American higher education, ranging from full-throated defenses of Confucius Institutes to threats. Among its most successful tactics, however, has been the effort to rebrand Confucius Institute-like programs under other names.

Many once-defunct Confucius Institutes have since reappeared in other forms.

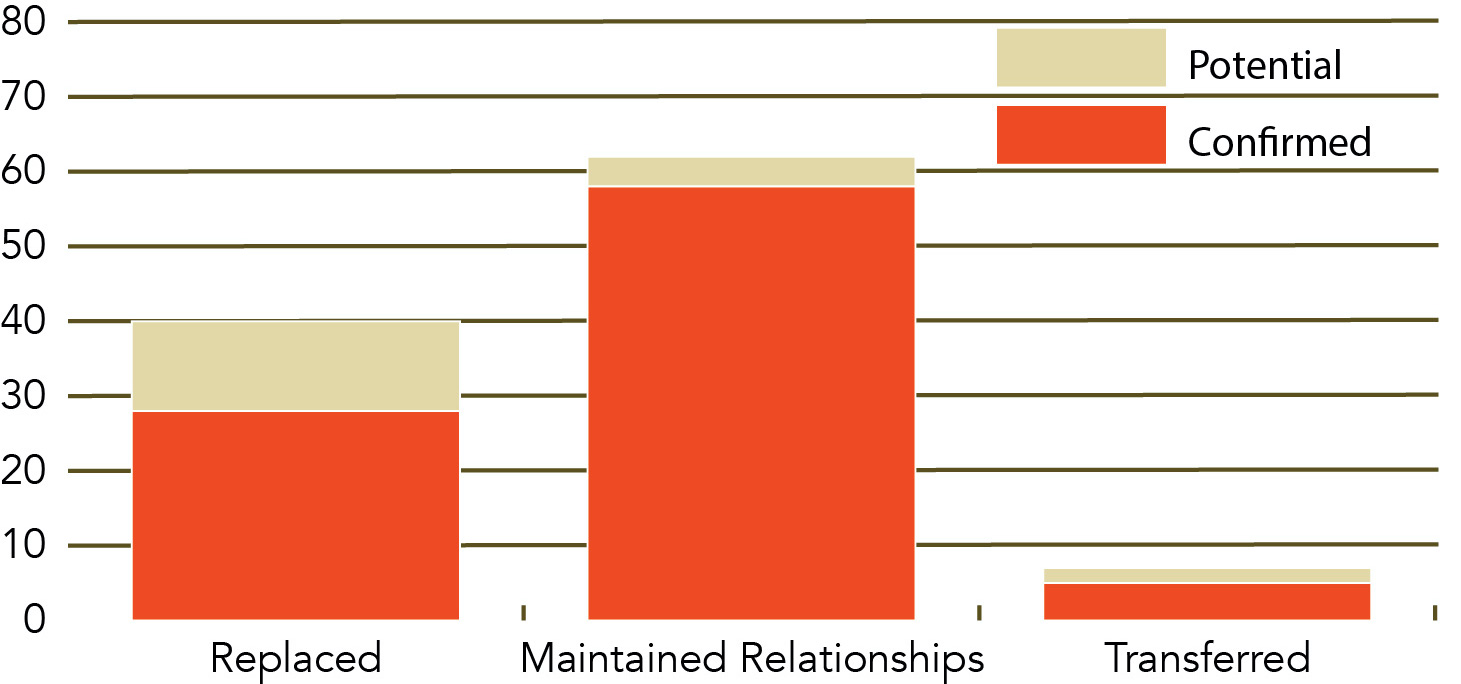

- 28 institutions have replaced (and 12 have sought to replace) their closed Confucius Institute with a similar program.

- 58 have maintained (and 5 may have maintained) close relationships with their former CI partner.

- 5 have (and 3 may have) transferred their Confucius Institute to a new host, thereby keeping the CI alive.

- The single most popular reason institutions give when they close a CI is to replace it with a new Chinese partnership program.

Institutions have entered new sister university agreements with Chinese universities, established “new” centers closely modeled on defunct Confucius Institutes, and even continued to receive funding from the same Chinese government agencies that funded the Confucius Institutes.

Such subterfuge matches the rebranding of the Hanban, the Chinese government agency that launched Confucius Institutes. Hanban has renamed itself the Ministry of Education Center for Language Exchange and Cooperation (CLEC) and spun off a separate organization, the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF), that now funds and oversees Confucius Institutes and many of their replacements.

This report documents what really happens when Confucius Institutes close. We find that:

- American universities are generally eager to replace their Confucius Institute with a similar program.

- The Chinese government initially responded to CI closures with shock and indignation, later with mere regret, and eventually by a template response letter that offers to support alternative programs.

- Many Confucius Classrooms (K-12 equivalents of CIs) have survived the closure of their sponsoring Confucius Institute.

- Many CI staff have migrated to CI-replacement programs at the same university. Some from a number of institutions have also congregated under the auspices of the Confucius Institute of Western Kentucky, hosted by Simpson County Schools after Western Kentucky University withdrew.

- Some CI textbooks and materials remain on the campuses of institutions that closed CIs.

- Many institutions, upon closing a CI, were forced to refund money to the Chinese government, sometimes in excess of $1 million.

- A handful of American nonprofits have been influential in shepherding CI programs to new homes, in particular BG Education Management Solutions, run by Terrill Martin, the former CI director at Western Kentucky University.

- Institutions’ foreign gift and contract disclosures under Section 117 of the Higher Education Act are spotty and unreliable. Some, including those for the University of Michigan and Arizona State University, have been retroactively edited to make continued Chinese funding anonymous.

We offer information on all 104 American institutions that have closed a Confucius Institute, as well as in-depth case studies of four: the University of Washington, Western Kentucky University, Arizona State University, and Purdue University.

Our case studies reveal the dynamics behind the Chinese government’s overtures and American universities’ eagerness to reciprocate. We recount the origin of the University of Washington’s Confucius Institute in a meeting between then Washington Governor Christine Gregoire and then Chinese President Hu Jintao at Bill Gates’ house in 2006, and how the CI developed unusually close relationships with corporations including Microsoft. The Confucius Institute relied on a third-party “fiscal agent,” shielding the University of Washington from federal transparency laws. The University of Washington, since severing ties with its Confucius Institute in order to maintain federal funding, not only transferred the Confucius Institute to Pacific Lutheran University but also sought legal loopholes that would permit it to re-establish ties with the Confucius Institute.

Western Kentucky University (WKU) installed as its founding Confucius Institute director Wei-Ping Pan, a leading expert in coal technology, at just the time the Chinese government was targeting coal technology for improper transfer to China. WKU parted with its CI by transferring it to a local school district, and immediately became embroiled in ongoing litigation over penalties regarding the Model Confucius Institute Building, constructed with a $1.5 million investment from the Chinese government. WKU’s former CI director, Terrill Martin, is now running both a nonprofit and a for-profit firm alongside Pan, focused on promoting engagement with China and salvaging Confucius Institute programs.

Arizona State University, when seeking to establish a Confucius Institute, first entered a “sister university” agreement with Sichuan University, a step it had been told would boost its application for a CI. That sister university relationship has survived the closure of the CI. In 2018, when Confucius Institutes were attracting national scrutiny, ASU Vice President of Governmental Affairs Matt Salmon traveled the nation praising Hanban. His comments at a National Press Club event, where he claimed (wrongly) that the Department of Defense had co-funded ASU’s CI, prompted Congress to amend the National Defense Authorization Act to bar DoD funding to universities with CIs. Salmon, a former member of Congress, is no longer at ASU and is now running for Governor of Arizona.

Purdue University built a number of partnerships with Shanghai Jiaotong University, some of which have survived the closure of its Confucius Institute. In a move echoed at many other universities, Purdue also moved many of its CI programs into other units at the university, directed by the former CI director but less traceable by the public.

This report draws on correspondence obtained via open records requests, contracts, and agreements between American universities and their Chinese partners, interviews, and site visits.

Online, at https://data.nas.org/confucius_institute_contracts you may browse our archive of documents for more than 80 universities. In Appendix I, you may see our chart of the current status of Confucius Institutes in the United States. (This chart is also available online at www.nas.org/blogs/article/how_many_confucius_institutes_are_in_the_united_states, where it will continue to be updated.)

We recommend that all universities not only close their remaining Confucius Institutes, but also withdraw from CI-replacement programs, including sister university relationships with Chinese universities.

We recommend that the federal government should:

- In the short-term, protect against post-CI influence campaigns, such as by amending the National Defense Authorization Act to target CI-replacement programs, and instituting new limits on other sources of federal funding to institutions that maintain a CI or similar program.

- In the long-term, protect against Chinese government influence operations, by instituting a tax on funds institutions receive via Chinese gifts and contracts, capping the amount of Chinese funding a college or university may receive before jeopardizing eligibility for federal funding, and prohibiting funding to colleges and universities that enter research partnerships with Chinese universities involved in China’s military-civil fusion.

- Commission a study on Confucius Classrooms, which are poorly understood but frequently survive the closure of their sponsoring CI. Meanwhile, the State Department should investigate potential visa abuse, as it did at CIs.

- Strengthen transparency requirements in Section 117 of the Higher Education Act by eliminating the disclosure threshold, requiring the name of the foreign donor, eliminating loopholes that permit foreign institutions to run gifts through foreign agents or university foundations, instituting stiff penalties, outlawing back-editing of data, and making disclosures user-friendly.

Because this report relied heavily on open records requests filed in 41 states, we also offer recommendations to streamline the FOIA process. Many states’ laws are needlessly complex, archaic, and so ineptly carried out they would seem designed to prevent, rather than empower, the American public’s access to public information. States’ open records laws should prevent unreasonable fees, specify a response time, include correspondence, penalize willful withholding of documents, narrowly define exemptions, and mandate infrastructure that support system-wide email searches.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Diana Davis Spencer Foundation for providing support for this project. We also thank members of the National Association of Scholars and others who helped us collect information on the universities we studied.

Introduction

When the first Confucius Institutes opened in 2005, Dan Mote hoped these Chinese government-sponsored programs would “teach the language and culture of China.” Mote was then president of the University of Maryland, the host of the first Confucius Institute in the United States, and he had helped the Chinese government come up with the idea of a Confucius Institute. “In 2001, China’s in the WTO, and we’re trying to think of some program we could create where we could help people understand what China is about,” Mote told People’s Daily, a Chinese Communist Party newspaper, in a 2020 profile. “Culture was the right topic because it’s clear, it’s not controversial.”1

Confucius Institutes did in fact adopt as their mission “enhancing the understanding of Chinese language and culture by people from all countries,” and repeated Mote’s hope that these centers would avoid controversy. They would “develop friendly relations between China and foreign countries, promote the development of the world’s multiculturalism, and build a harmonious world,” according to the Confucius Institute Constitution.2

The Chinese government set up the Confucius Institute Headquarters under the umbrella of the Hanban, an agency of the Chinese Ministry of Education, to oversee and fund Confucius Institutes. The Hanban would recruit foreign universities, pair them with a Chinese university, and select Chinese teachers, textbooks, and other supplies. Hanban would supply annual funding, which host universities were to match, usually by way of donated classrooms and office space.

Mote won the “Chinese Government Friendship Award” in 2014 in part for his efforts to launch the Confucius Institutes. For a time the Confucius Institute program far exceeded his expectations. “The thinking was fifty in the world and ten in the United States,” he told People’s Daily. “It turned out to be much more attractive than we thought.”

In the United States alone, some 118 educational institutions have hosted a Confucius Institute. These include 110 colleges and universities, seven school districts, and one private educational organization, the China Institute. Around 500 American K-12 schools have hosted Confucius Classrooms, a smaller version of the Confucius Institute, aided in part by the Asia Society, an American nonprofit that runs a network of some 100 Confucius Classrooms.3 Others received individual Chinese teachers via the Chinese Guest Teacher Program operated until recently by the Hanban and the College Board, the nonprofit best-known for administering the SAT and Advanced Placement tests.

But even more swiftly than they appeared, Confucius Institutes have closed. At the end of 2021, 104 American institutions had closed their Confucius Institutes or were in the process of doing so. The University of Maryland, Dan Mote’s institution, shut its Confucius Institute in 2020.

Why did Confucius Institutes close? Chronologically, most closures followed a nationwide reckoning with the sheer scale of the Chinese Communist Party’s overseas influence campaign. Confucius Institutes, the Thousand Talents Program, the Chinese Students and Scholars Association—these and many other Chinese government-backed programs grew to such size that the United States started paying attention, and quickly realized that the Chinese government’s largesse came with strings attached.

The FBI began discussing higher education’s “naivete.”4 The State Department warned of “malign influence” via Confucius Institutes.5 The Department of Education and the Department of State issued notices to school districts with Confucius Classrooms.6 Members of Congress—both Republicans and Democrats—began writing their constituent universities and introducing bills to address Confucius Institutes. The National Defense Authorization Act was amended twice, in 2018 and again in 2020, to bar universities with Confucius Institutes from certain Department of Defense grants.

But wariness about China’s ulterior motives is not the reason most colleges and universities gave when they closed their Confucius Institutes. They generally expressed regret at being “forced” to do so by federal policies. Several ran afoul of visa regulations and closed upon being audited by the State Department. Others claimed their students weren’t interested in learning Chinese.

Some gave excuses. University of California-Los Angeles spokesman Ricardo Vazquez told us UCLA closed its Confucius Institute in part because of “an urgency to focus the university’s resources and expertise on pressing world issues, such as the climate crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.”7

Several, including the University of Michigan, sought to retain Hanban funding even after the closure of the Confucius Institute.8 Federal disclosures show the university did in fact receive more than $300,000 from Hanban in May and June 2019, just as the Confucius Institute was closing in June 2019 (though these disclosures have since been deleted from the Department of Education’s website).

Other universities worked to rehouse the Confucius Institute elsewhere, as the University of Washington did when it passed its CI to Pacific Lutheran University in 2019. Western Kentucky University, too, recruited a local school district, the Simpson County Public Schools, to take over its Confucius Institute in 2019, a transfer aided in large part by a consulting group run by Terrill Martin, former director of the Confucius Institute.

Many created something substantially similar to a Confucius Institute under a different name, as did Georgia State University, the College of William and Mary, Michigan State University, and Northern State University.

In some cases, the Chinese government appears to have anticipated the possibility of Confucius Institute closures. It encouraged universities to form official partnerships that existed outside the Confucius Institutes and therefore could survive a Confucius Institute closure. Arizona State University, one of our case study institutions, signed a “sister university” agreement with Sichuan University in 2006, at the same time it was negotiating a separate agreement for the Confucius Institute, also run in partnership with Sichuan University.

The Asia Society, the sponsor of the Confucius Classrooms Network, has gone a step further and simply renamed its program the “Chinese Language Partner Network.”9 The Asia Society evidently realized that the name “Confucius Institute” had become a major PR problem and decided to continue the program by camouflaging it.

Have Confucius Institutes really closed? Or have they just transformed into something allegedly new but substantially similar?

This report describes what happens when a Confucius Institute closes. We describe our findings at all 104 institutions that have closed or are in the process of closing a Confucius Institute, and we examine four universities in closer detail: the University of Washington, Western Kentucky University, Arizona State University, and Purdue University.

We also offer, as an online database at https://data.nas.org/confucius_institute_contracts, an archive of documents for over 80 universities. This archive is the result of more than 100 Freedom of Information requests that we filed, producing several thousand pages of documents. In the archive you can see original Confucius Institute contracts, correspondence with the Chinese government, financial records regarding the funding of Confucius Institutes and their replacement programs, and more.

In this report, we document the reasons institutions give for closing their Confucius Institutes, and describe what effect that decision had on the university. We ask what happened to the CI staff, the books the Hanban had donated, and the programs the Confucius Institute was running. We consider how the closure of the Confucius Institute affected the university’s relationship with universities in China, especially the Chinese university that had been its CI partner.

We also describe three types of action taken after CI closure: replacing the CI, maintaining a partnership with the Chinese partner university, or transferring the CI to a new home.

Replacing the CI means the institution retained, on its own campus and as part of its own programming, substantial pieces of its Confucius Institute under a different name. This includes institutions that formed new replacement programs with the Chinese university that had partnered in the Confucius Institute. It also includes institutions that formed new China-focused centers that took on Confucius Institute staff, Confucius Institute programs, or funding from the Center for Language Exchange and Cooperation (CLEC) or the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF), the successors to Hanban.

Institutions that maintained partnerships with Chinese universities frequently kept or developed “sister university” relationships. Others separately entered research or exchange agreements.

By transferring the CI, the university found a new home for the Confucius Institute and its associated Confucius Classrooms. In some cases this meant recruiting another university to take over the Confucius Institute, so that the Institute itself never closed but merely changed hosts. In other cases, the university made arrangements for local K-12 Confucius Classrooms, which are frequently a core component of each Confucius Institute.

We expected to find at least some examples of a fourth type of closure, a full closure. A full closure, in our definition, means a university terminated all agreements with the Hanban; did not enter a new agreement with either of the Hanban’s two successor organizations, CLEC or CIEF; did not enter into or retain an agreement with a Chinese partner university that is substantially similar to the agreement that formed the Confucius Institute; did not retain a “sister university” relationship with a Chinese university; did not rehouse the Confucius Institute or any of its programs; did not retain Confucius Institute staff; and did not retain any Hanban-supplied textbooks or other materials.

In some cases, we have insufficient information to classify a university. But in no cases are we sufficiently confident to classify any university as having fully closed its Confucius Institute. All four of our case study institutions showed evidence of continued collaboration with the Chinese government. Of the additional 100 colleges and universities that have closed a CI, our research could not confirm a single complete closure of the Confucius Institute.

Overall we find that the Chinese government has carefully courted American colleges and universities, seeking to persuade them to keep their Confucius Institutes or, failing that, to reopen similar programs under other names. American colleges and universities, too, appear eager to replace their Confucius Institutes with other forms of engagement with China, frequently in ways that mimic the major problems with Confucius Institutes.

What Are Confucius Institutes?

Before we describe the closure of Confucius Institutes and their replacement with similar programs, we should clearly define what a Confucius Institute is.

As we described in greater detail in our 2017 report, Outsourced to China: Confucius Institutes and Soft Power in American Higher Education, Confucius Institutes are centers that teach Chinese language and culture. They are almost always located on a college or university campus, though they may occasionally be located at a K-12 school district or nonprofit organization. Confucius Institutes are set up as partnerships between a host institution, a Chinese partner (usually a Chinese university), and a Chinese government agency.

Until recently, that Chinese government agency was the Hanban, also known as the Office of Chinese Language Council International and as the Confucius Institute Headquarters. As criticism of Confucius Institutes spread, the Chinese government reorganized and rebranded the Hanban as the Center for Language Exchange and Cooperation. This new organization, CLEC, has also spun off another new organization, the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF). Although CIEF is now in charge of Confucius Institutes, CLEC remains active in setting up and funding similar programs under a variety of names other than “Confucius Institute.”

The Chinese government undertook this reorganization in an attempt to salvage Confucius Institutes’ reputations, which we discuss further in the section “Rebranding Confucius Institutes.”

The Hanban funds each Confucius Institute, often around $100,000 per year, and it asks host institutions to match those funds with their own contributions, usually classroom and office space. Sometimes the Hanban provides substantially more money. Stanford University received $4 million (which it matched) to endow a professorship. Western Kentucky University, one of our four case study institutions, received $1.5 million, which it also matched, to construct a building for the Confucius Institute.10 When the university closed its Confucius Institute in 2019, it began a still-ongoing dispute with the Hanban as to how much money it owes Hanban as repayment.

In addition to providing funding, the Hanban sent free textbooks (the standard offer was 3,000) and provided teachers and a Chinese co-director. The teachers and co-director were usually from the Chinese partner university and came on two-year contracts. They were contracted with and paid by the Hanban, which usually also covered their living expenses while working at the Confucius Institute, airfare to and from China, and health insurance. The Chinese partner university worked with the Hanban to propose a slate of candidates, from which the host university was allowed to select. Universities frequently claimed “complete control” of the hiring process, but in reality they controlled only the final selection from among a limited number of pre-screened candidates put forward by the Hanban.

Confucius Institutes offered classes, usually on Chinese language, and frequently hosted cultural events, such as Chinese tea ceremonies, lunar new year celebrations, guest lectures, and musical performances. Sometimes these classes were offered for-credit, meaning that students paid regular tuition and received credits that counted toward their degrees. At least one university, Rutgers, previously permitted students to fulfill their general education distribution requirements by taking Confucius Institute courses. Often Confucius Institutes offered not-for-credit classes, open to both college students and members of the public.

The Hanban heavily encouraged the creation of Confucius Classrooms at K-12 schools as well, and many of these developed as offshoots of a Confucius Institute at a college or university. Confucius Classrooms operate as smaller-scale versions of Confucius Institutes, offering Chinese language courses to elementary and secondary schools. In some states, such as Utah, Confucius Classroom teachers have been assigned to teach in language immersion programs, through which they teach not only language, but also primary subjects, including some like history or economics that the Chinese government may have a special interest in.

While many Confucius Institutes have closed, our research suggests that many Confucius Classrooms remain open.

Criticisms of Confucius Institutes

Groups as diverse as the FBI, the American Association of University Professors, the Department of State, the Department of Education, as well as the National Association of Scholars, have criticized Confucius Institutes.

Marshall Sahlins, in a seminal 2013 piece for The Nation, described Confucius Institutes as propaganda programs that “routinely and assiduously… hold events and offer instruction under the aegis of host universities that put the PRC in a good light.”11 Sahlins’ criticisms helped sway his institution, the University of Chicago, to cancel its Confucius Institute in 2014—the first major CI closure in the United States.12 Sahlins’ subsequent book, Confucius Institutes: Academic Malware, chronicled incidents in which Confucius Institutes engaged in various abuses of higher education, such as pressing for disinvitations of the Dalai Lama or misleading students about the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

The American Association of University Professors, too, has called Confucius Institutes “partnerships that sacrificed the integrity of the university.” It recommended in 2014 that “universities cease their involvement in Confucius Institutes” unless they could demonstrate unilateral control over the Institute and full academic freedom for teachers.13

We, the National Association of Scholars, investigated twelve Confucius Institutes for a 2017 report, Outsourced to China: Confucius Institutes and Soft Power in American Higher Education. That same year, Chinese-Canadian documentary journalist Doris Liu released In the Name of Confucius, looking at Confucius Institutes in Canada. NAS’s report documented distorted or censored discussions of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, the status of Taiwan, and China’s aggression toward Tibet. We also exposed secret contracts universities had signed with the Chinese government, granting the Hanban power to hire teachers, select curricula, and exercise veto power over all Confucius Institute programs and events.

FBI Director Chris Wray in 2018 testified that his agency took “investigative steps” at Confucius Institutes, because China uses “nontraditional collectors, especially in the academic setting” to engage in espionage.14

In 2019 two federal bodies issued reports on Confucius Institutes. The Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations found that China spent $158 million on U.S.-based Confucius Institutes, and at least $2 billion worldwide since 2006. It described Confucius Institutes as “part of China’s broader, long-term strategy” to develop soft power and “export China’s censorship” to college campuses. It recommended that without full transparency regarding Confucius Institutes and reciprocity for American cultural outreach on Chinese campuses, “Confucius Institutes should not continue in the United States.”15

The report from the Government Accountability Office downplayed concerns about Confucius Institutes, though in a manner that frequently stoked new concerns. Having documented that Confucius Institute teachers were selected from a pool of candidates put forward by Hanban, for instance, it reported that college and university officials “expressed no concerns about the process for hiring teachers,” suggesting that universities were either unaware of or indifferent to China’s stifling of their teachers’ academic freedom.16

Then-U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo called Confucius Institutes “part of the Chinese Communist Party’s global influence and propaganda apparatus” in a 2020 statement that officially designated the Confucius Institute U.S. Center as a foreign mission of the People’s Republic of China.17 A few days later then-Undersecretary of State Keith Krach wrote to all college and university governing boards, warning that Confucius Institutes “exert malign influence on U.S. campuses and disseminate CCP propaganda.”18

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos issued a joint letter with Pompeo in October 2020, warning state commissioners of education about “an authoritarian slant in curriculum and teaching” at Confucius Institutes and Confucius Classrooms.19

Students, too, have stepped forward with concerns about Confucius Institutes. Students like Rory O’Connor founded the nonprofit Athenai Institute in 2020 to push back against Chinese Communist Party influence on American colleges. In its first public act, Athenai issued a “Washington Appeal” outlining policies to protect American colleges, including “The immediate and permanent closure of all Confucius Institutes in the United States.”20 The leadership of both the College Republican National Committee and the College Democrats of America, plus some two dozen activists and Chinese dissidents, signed the Appeal.

Such concerns abound in other nations, as well. The U.K. Conservative Party Human Rights Commission issued a 2019 report concluding that “Confucius Institutes as they are currently constituted threaten academic freedom and freedom of expression in universities around the world and represent an endeavour by the Chinese Communist Party to spread its propaganda and suppress its critics beyond its borders.”21 In April 2020, Sweden became the first European country to end all Confucius Institute partnerships.22

In Japan, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga has announced plans to launch a formal inquiry into Confucius Institutes.23 In Scotland, members of the Educational Institute of Scotland, a teacher’s union have called for an investigation of Confucius Institutes.24

China’s Defense and Rebranding of CIs

The Chinese government has used an “all-of-the-above” approach to defending its Confucius Institutes. It has sought to persuade Americans that Confucius Institutes are innocuous, as with a 2018 National Press Club event sponsored by the Confucius Institute U.S. Center, where ASU’s Matt Salmon claimed the Confucius Institute was “a real, real blessing” co-funded by the Department of Defense. The Chinese government has also threatened the U.S. with hostility, as in July 2021, when Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Xie Feng delivered a list of “wrongdoings” it demanded the U.S. correct, including assaults on Confucius Institutes.25

For a time, Hanban sought to reassure its American partner universities of the value of a Confucius Institute, and to coach them in the art of defending their Confucius Institutes. Records requests reveal that Hanban mailed to many American hosts of Confucius Institutes a 2019 letter rebutting “recent groundless criticism” and seeking suggestions “on how to better develop our Confucius Institute under such circumstances.” The letter, signed by Ma Jianfei, Deputy Chief Executive of Confucius Institute Headquarters, proceeded to “clarify the mission of the Confucius Institutes,” provided a list of talking points, and urged “proactive” measures such as making Confucius Institute contracts public—the secrecy of which critics had frequently commented on.26

Some Chinese universities, too, wrote to their American partners, urging them to maintain their Confucius Institutes despite recent counter-pressure. In April 2019, East China Normal University President Qian Xuhong wrote to University of Oregon President Michael H. Schill, saying he had “learnt that the Confucius Institute is in face of some difficulties.” Xuhong assured Schill that East China Normal University, “in the name of Partner University, are more than willing to continuously join hands with you to find out suitable ways to settle the difficulties.”27

In addition to defending Confucius Institutes outright, the Chinese government has also relied on the art of subterfuge, rebranding Confucius Institutes under different names and massaging their outlines to be less obvious to the public, and better camouflaged within the university. This has proven an effective strategy, and at least 38 universities that closed a Confucius Institute have replaced or sought to replace it with something similar.

The Chinese government knows the United States is well on its way to a post Confucius Institute world, and it is prepared.

Defending Confucius Institutes

The Chinese government has not shied away from full-throated defenses of its Confucius Institutes. Sometimes it does so in its own name. Often, it arranges for platforms and avenues from which American supporters of Confucius Institutes may speak.

The Confucius Institute U.S. Center (CIUSC) paid for fourteen national press releases via PRNewswire between 2018 and 2020,28 including an “Open Letter to Editors Nationwide.”29 In 2018 it broadcast on DirectTV and on YouTube a ten-episode TV series featuring presidents of American universities and corporations praising Confucius Institutes.30

CIUSC went so far as to book the National Press Club for a panel discussion in 2018, moderated by John Holdren, CEO of the U.S.-China Strong Foundation. The event featured four top administrators at universities with Confucius Institutes, each speaking highly of the Chinese government’s generosity in educating American students.

Perhaps most enthusiastic among the panelists was Matt Salmon, a former member of Congress from Arizona and at that time vice president of government affairs at Arizona State University. (ASU is one of this report’s case study institutions, detailed later in this report.).

Salmon called the Confucius Institute “a real, real blessing.” Then, in the most-quoted words of that event, Salmon remarked, “The Department of Defense has invested at Arizona’s Confucius program.” He continued, “I find it a little bit incredulous” that anyone considers Confucius Institutes “a security threat,” noting that “if the DoD had serious reservations that the CI was some kind of threat to national security, they wouldn’t have in their wildest dreams provided funding.”31

Salmon had actually overstated the cooperation between ASU’s Confucius Institute and its Department of Defense-funded Chinese Language Flagship Program, but the CCP mouthpiece China Daily immediately took Salmon’s words at face-value in a puff piece on Confucius Institutes.32 Shortly thereafter, Senator Ted Cruz added language to the National Defense Authorization Act barring the DoD from funding Confucius Institutes.33

That law, and similar measures considered by state governments, has prompted additional supporters of Confucius Institutes to step forward. “The U.S. government should stop vilifying China’s Confucius Institutes,” former China correspondent Ian Johnson wrote for the Times in a March 2021 piece headlined, “Mr. Biden, Enough With the Tough Talk on China.” Johnson compared Confucius Institutes to the UK’s British Council—a comparison Hanban has long promoted—and advised that although CI courses should not grant college credit, they should “be able to function” off-campus.34

A few weeks later Jamie P. Horsley worried about “the end of CIs after a 15-year, generally controversy-free record in the United States.” Horsley, who is a senior fellow at Paul Tsai China Center, a visiting lecturer in law at Yale Law School, and a visiting fellow in Foreign Policy at the John L. Thornton China Center of the Brookings Institution, called for “a new policy on Confucius Institutes,” which amounted to greater government funding for Chinese language instruction and an end to laws (like the NDAA) that Horsley sees as “forcing cash-strapped universities to choose between federal funding and properly managed CI programs.”35

Some universities have also stepped forward to praise their Confucius Institutes. Some have since reneged, like UCLA. In 2018 UCLA spokesman Ricardo Vazquez told the student newspaper The Daily Bruin that despite FBI Director Chris Wray’s concerns about Confucius Institutes, UCLA considered its Confucius Institute “especially important in a city like Los Angeles.”36 (Two years later the UCLA Confucius Institute did in fact close.)

But a number of Confucius Institutes remain open in the United States (see Appendix IV), and some are vocal. Troy University dispatched Chancellor Jack Hawkins to lobby against an Alabama bill that would have barred state universities from hosting Confucius Institutes.37 Troy may have an ulterior motive to retain its Confucius Institute. Its most recent agreement with Hanban, signed in 2018 for a five-year term, permitted Hanban to cancel the agreement early, but would penalize Troy’s early withdrawal. Troy would owe “all the damages incurred” to Hanban, including “all the investment made under this Agreement, the legal expense and the indemnity for defamation.”38

Most universities that favor Confucius Institutes, though, have chosen to quietly let them go, only to reopen a similar center under a new name.

Rebranding Confucius Institutes

The Hanban, the Chinese government agency whose name has become nearly synonymous with “Confucius Institute,” in July 2020 renamed itself the Ministry of Education Center for Language Exchange and Cooperation, or CLEC. CLEC then spun off a new nonprofit organization, the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF), to run Confucius Institutes.

China’s Global Times presented the rebranding as a way to “disperse the Western misinterpretation that the organization served as China’s ideological marketing machine.”39 Hanban’s transformation did, in fact, execute a plan the Chinese government had announced to “reform” the image of Confucius Institutes, retooling them to “better serve Chinese diplomacy.”40

As early as 2019, Hanban was preparing to modify Confucius Institutes to make them more palatable to the West. That year, Hanban staff led a session at the 2019 National Chinese Language Conference, an annual conference Hanban started in 2007 before stepping back as a behind-the-scenes funders, while the Asia Society and the College Board became the public organizers.41 Hanban gathered some 60 CI directors at the conference to discuss threats to the future of Confucius Institutes. One attendee, Aihua Liao, the assistant director of the Confucius Institute at the University of Washington, recalled that Ma Jianfei of Hanban told attendees “US CIs are now facing challenges and many are to be closed but Hanban sees it as an opportunity to restructure/remap the CIs across the world.” Ma also advised that, in Liao’s words, “Hanban will support whichever way that could help CI to relocate due to conflict with DoD funding or other federal policies.”42

In 2020, the Hanban consulted with Nathaniel Ahrens, executive director of the American Mandarin Society, to help Hanban reshape the image of Confucius Institutes. Our FOIA requests show that in 2020, the Washington State China Relations Council prepared a webinar on Confucius Institutes, featuring Ahrens. An invitation to Jeffrey Riedinger, vice provost of the University of Washington, described Ahrens as having “worked on the issue with the Hanban” to “help them reorganize the concept” of Confucius Institutes to more closely match Germany’s better respected Goethe Institutes.43 The webinar was notable not only for its emphasis on “reorganizing” Confucius Institutes to make them more appealing, but also because it sought to include the University of Washington, which had already closed its Confucius Institute but could, in theory, be persuaded back to participation.

Hanban’s reorganization changes little about the substance of Confucius Institutes. CIEF is technically a nongovernmental nonprofit, which defenders of Confucius Institutes say makes null past criticisms that Confucius Institutes are run by the Chinese government. In reality, the line between the Chinese government and its offshoot organizations is paper-thin. CIEF is under the supervision of the Chinese Ministry of Education and is funded by the Chinese government.

CLEC continues to handle most of the work the Hanban once did. Per China’s Global Times, it maintains responsibility to “coordinate Chinese language learning resources, make standards for teaching and support training for teachers and compilation of books.”44 Some universities that kept their Confucius Institutes after CLEC and CIEF split signed new memoranda of understanding with both CLEC and CIEF, our records requests show.45 At universities that closed their Confucius Institutes, CLEC offered to sponsor a new, similar center. Some, like Northern State University, took CLEC up on this offer.46

Hanban’s reorganization has prompted a cascade of rebranding efforts at American universities. Many are eager to ditch the now-toxic name “Confucius Institute” but retain funding and close relationships with Chinese institutions. These institutions have sought to keep aspects of a Confucius Institute without using the name. They understand that the brand “Confucius Institute” has become a political liability, yet they hope to maintain their previous engagement with the Chinese government.

And not just American universities: the Asia Society, too, has kept its Confucius Classroom open but renamed its network of Confucius Classrooms the “Chinese Language Partner Network,” evidently to deter criticism.47

The scale of these rebranding efforts signals how thoroughly the political landscape has changed in the last few years. In our 2017 report, Outsourced to China, we expressed doubt that universities could extricate themselves from Confucius Institutes without jeopardizing other relationships in China. “Confucius Institutes have grown into a central node of US-Chinese academic exchanges, making it increasingly difficult for universities to withdraw from Confucius Institutes without jeopardizing other financial relationships,” we wrote. “Withdrawing from hosting a Confucius Institute is a difficult task…. The agreement may be cancelled before it comes up for its five-year renewal period, but only if there is ‘a national emergency, war, prohibitive government regulation or any other cause beyond the control of the parties.’”48

Changes in federal policy have enabled many colleges and universities to terminate their Confucius Institute contracts using the force majeure clause we quoted in our 2017 report. However, increasingly the Chinese government has also welcomed the closures of Confucius Institutes in the United States as an opportunity to extend its influence in new ways.

The Chinese government’s acquiescence in the closure of Confucius Institutes suggests that even in their waning, Confucius Institutes have served the Communist Party well. A central goal in establishing Confucius Institutes, for the Chinese government, was to bring colleges and universities into closer relationships with Chinese institutions.

Confucius Institutes built those relationships and now fall away, unneeded, like a scaffold after the building is complete.

CLEC and CIEF: Hanban’s Successors

CLEC and CIEF, both successors to the Hanban, appear to duplicate each other in some ways. Both run overseas Chinese language and culture programs. When colleges and universities closed their Confucius Institutes, many wrote to both CLEC and CIEF, and sometimes received responses from both.

But overall we find that CLEC, which is the new name for the Hanban, is running overseas Chinese language programs that are not called Confucius Institutes. CIEF is running Confucius Institutes. Colleges and universities that continue to host Confucius Institutes are doing so under the umbrella of CIEF. Colleges and universities that closed their Confucius Institutes but are operating other Chinese language programs are often doing so with support from either a Chinese university or from CLEC. However, at least one university, Wayne State University, was offered a non-Confucius Institute program, the “Chinese Language Center,” which would have been funded by CIEF.49

Any distinctions between the two organizations are technical. As far as we can tell, CLEC and CIEF run extremely similar programs whose primary difference seems to be in name only.

Charting Confucius Institutes by Year

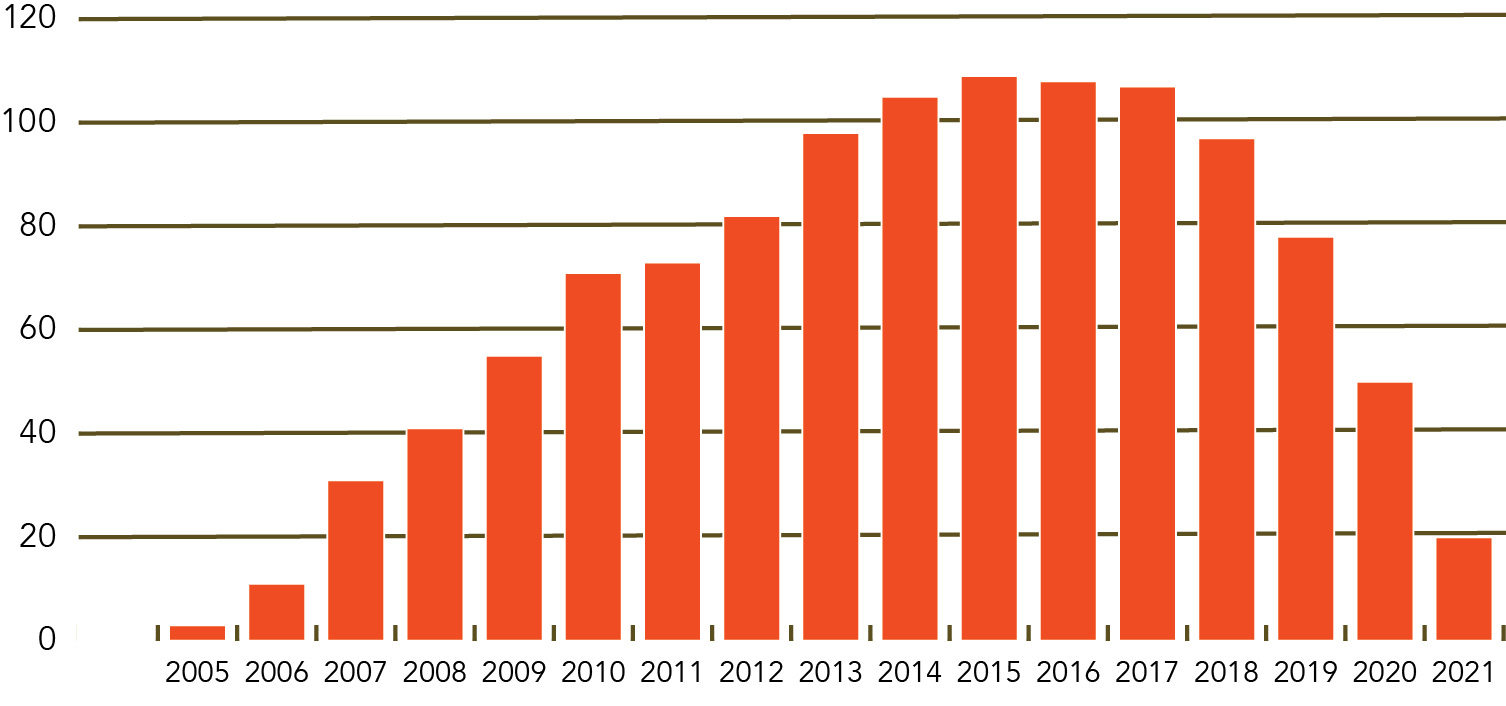

One hundred eighteen American institutions have hosted a Confucius Institute. Three opened in 2005: the University of Maryland (the first in the U.S.), Chicago Public Schools, and China Institute, a private educational nonprofit in New York City. One year later the number had jumped to eleven, and by 2007 to 31. The number of Confucius Institutes peaked in 2015, when there were 109.

Confucius Institutes by Year

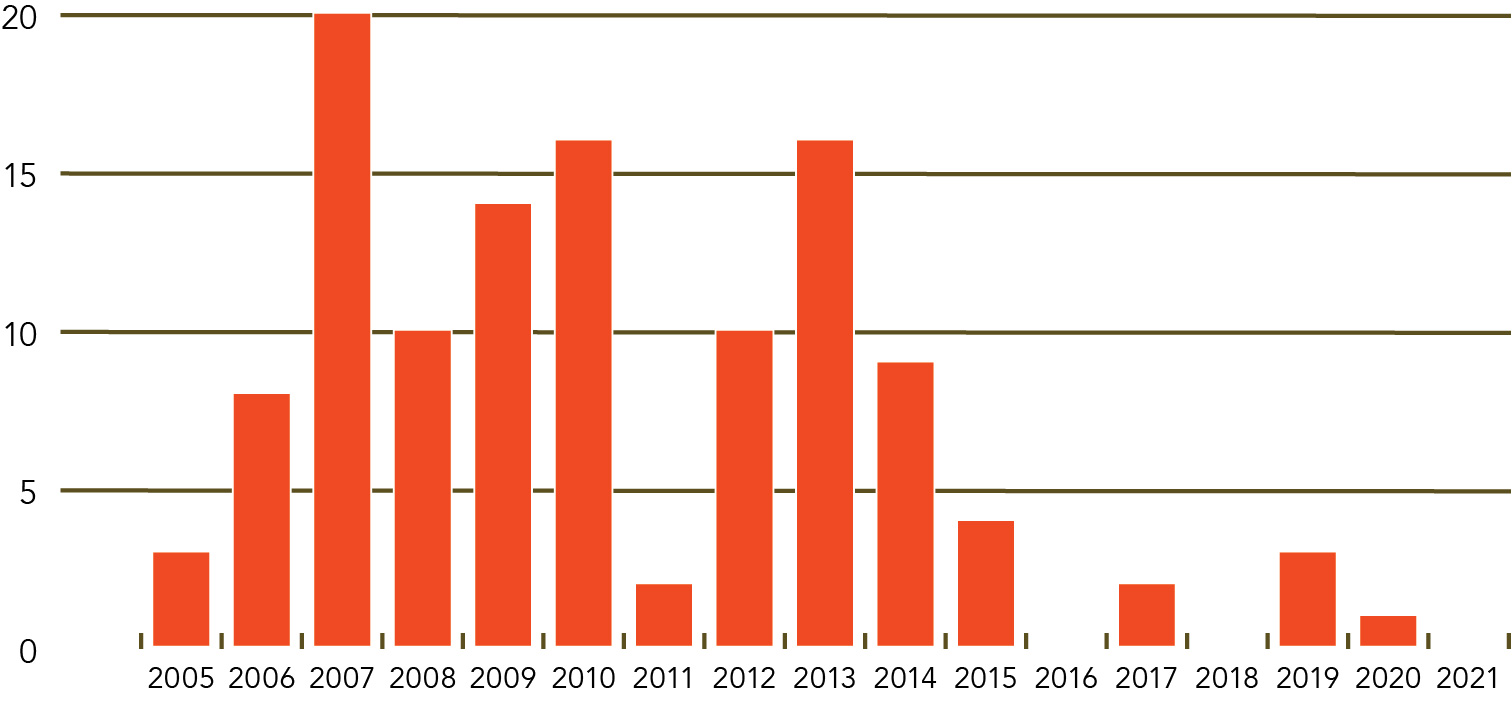

The number of new Confucius Institutes opening per year in the United States has varied greatly. Notably, CIs have continued to open at new institutions even after the rise of concerns about Confucius Institutes’ integrity and neutrality.

Confucius Institutes Opening Per Year

As recently as 2020, Pacific Lutheran University became the new host of the Confucius Institute of the State of Washington, after the University of Washington transferred the program to PLU. In 2019, three new institutions opened a CI. Two of these had transferred from departing CI hosts: Simpson County Schools took on Western Kentucky University’s CIs, and San Diego Global Knowledge University took San Diego State University’s. One institution, Medgar Evers College, opened a new CI that had not previously existed elsewhere.

The first Confucius Institute to close was Dickinson State University, which canceled its Confucius Institute agreement in February 2012, less than a year after it had signed documents with the Hanban, and before the Confucius Institute had even officially opened. News of the Confucius Institute signing coincided with a public realization that the university had served as a diploma mill for foreign students seeking Western credentials. An audit found that 743 out of 816 students enrolled via partnerships with Chinese and Russian universities lacked English proficiency test scores, submitted fraudulent transcripts, or earned insufficient credits for the degrees they were awarded.50 Dickinson’s accreditor put the university “on notice,”51 and the Confucius Institute closed as well.

The second Confucius Institute to close was at the University of Chicago, in a major decision that made national news. The University announced its decision in September 2014,52 just five months after 108 faculty members signed an open letter denouncing the Confucius Institute53 and three months after the American Association of University Professors came out against Confucius Institutes.54 Within days Pennsylvania State University, too, said it was closing its Confucius Institute.55

The demise of the Confucius Institute at the University of Chicago was in part the result of sustained criticism from Marshall Sahlins, an emeritus professor of anthropology at the university. Sahlins had in 2013 written “China U.” for The Nation, the first long-form critique of Confucius Institutes. In that piece, Sahlins had not shied away from criticizing his own university, quoting a colleague, Ted Foss, the deputy director of Chicago’s Center for East Asian Studies, that “I can put up a picture of the Dalai Lama in this office. But on the fourth floor [at the Confucius Institute], we wouldn’t do that.”56 Sahlins had been influential in the faculty petition against the Confucius Institute, which read, in part, “the University is participating in a worldwide, politico-pedagogical project that is contrary in many respects to its own academic values.”57

But the Chinese government also had its own missteps to blame. Having learned about faculty opposition to the Confucius Institute, Hanban director-general Xu Lin reportedly contacted the university to convey that “Should your college decide to withdraw, I’ll agree” – a sentence the New York Times reported “in Chinese … carries connotations of a challenge.” The Jiefang Daily enthusiastically declared that Xu’s “attitude made the other side anxious. The school quickly responded that it will continue to properly manage the Confucius Institute.”58

When the University of Chicago announced its termination of the Confucius Institute, it cited “recently published comments about UChicago in an article about the director-general of Hanban,” which it took as “incompatible with a continued equal partnership.”59

Penn State, for its part, said it terminated the Confucius Institute because some of the university’s “goals are not consistent” with those of the Hanban.60

The action taken by the University of Chicago, despite its national attention, failed to spark a sustained movement. Besides Penn State, no other universities closed Confucius Institutes in 2014. Nor did any the following year. In 2016, Pfeiffer University did—by way of transferring its Confucius Institute to the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Only in 2017 did the sustained downward trajectory of Confucius Institutes begin.

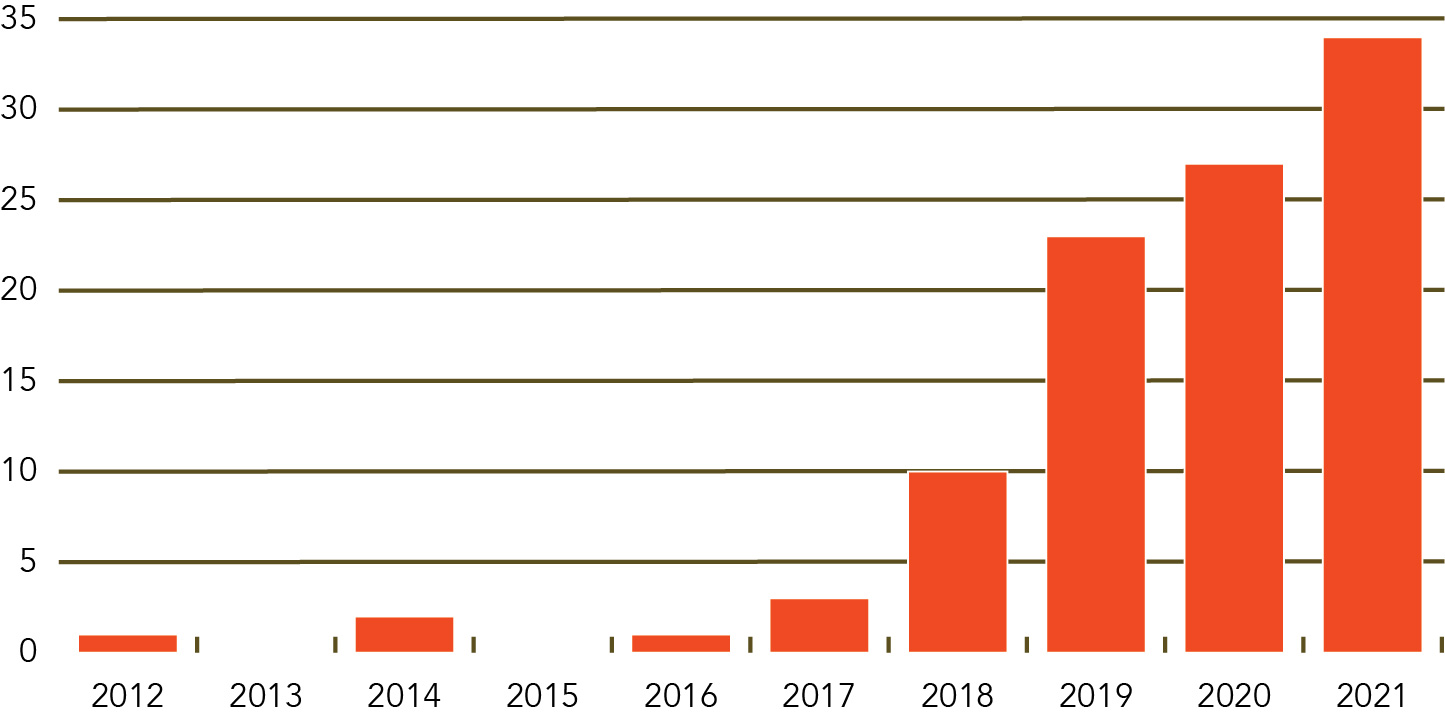

The following chart shows the number of Confucius Institutes that closed per year. In 2017, three closed, followed by ten in 2018, 23 in 2019, 27 in 2020, and 34 in 2021. Already in 2022, four more have closed or have announced they will close by the end of the year (Houston Independent School District, Southern Utah University, Valparaiso University, and University of Akron). Another two have announced their intention to close but have given no date (Alabama A&M University and Bryant University).

Confucius Institute Closures Per Year

Why Confucius Institutes Close

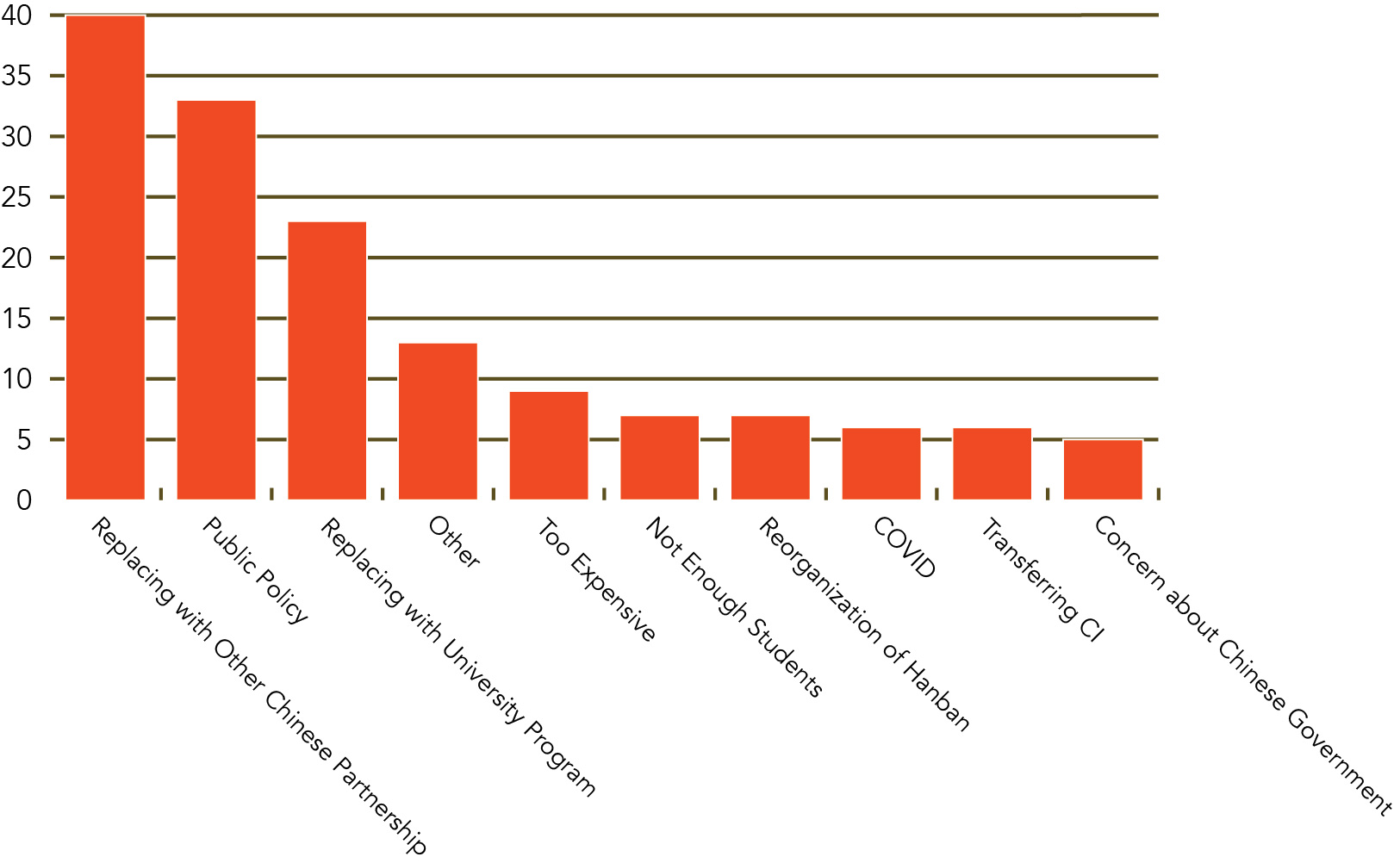

Most of the criticisms surrounding Confucius Institutes involve threats to national security, infringements of academic freedom, and the problem of censorship. But these are rarely the reasons colleges and universities give when they announce plans to close a Confucius Institute. The most frequently cited reasons are the development of alternative partnerships in China, and changes in U.S. public policy.

Only five of 104 institutions cited concerns regarding the Chinese government’s relationship to Confucius Institutes—and two of these five proclaimed that all national alarm was due to the mismanagement of Confucius Institutes by other universities.

We tracked the reasons colleges and universities have given for closing their Confucius Institutes. We drew primarily on four sources: letters the institutions sent to the Chinese government or their Chinese partner university; letters the institutions sent to a U.S. government body, often the Department of State; internal announcements to the staff, faculty, and campus community; and statements published on the institutions’ own websites or published by the media. In a few cases where we could identify no stated reason, we contacted the institution and asked for a statement. By using both public and internal statements made by institutions, we put together the most complete explanation to date of the motivations behind Confucius Institute closures.

In our documents database online at https://data.nas.org/confucius_institute_contracts, you may download and read these documents for yourself. In Appendix II, you may also see a chart offering quotes from the universities on why they closed their CI.

We organized these reasons into ten categories. They are, in order of popularity: replacing the Confucius Institute with a new Chinese partnership (40); U.S. public policy (33); replacing with a university-run Chinese program (23); the expense of hosting a Confucius Institute (9); insufficient students (7); the reorganization of the Hanban (7); COVID-19 (6); transferring the CI to another institution (6); and concern about the Chinese government (5). Thirteen colleges or universities gave unique reasons we categorized as “other.” Seventeen gave no reason whatsoever.

Some institutions gave multiple reasons, and we counted them all. Rather than attempt to reduce each institution to a single reason (a process with a high degree of subjectivity), we permitted institutions unlimited reasons for the purpose of our study. Hence the total number of reasons cited (149) is larger than the number of institutions that closed a Confucius Institute (104).

Reasons for Closing Confucius Institutes

Replacing Confucius Institutes with New Partnerships in China

Setting up a new partnership with a Chinese institution is the single most frequently cited reason for closing a Confucius Institute. Forty of 104 institutions (38 percent) say they are replacing the Confucius Institute with a new partnership, often one that is quite similar to the Confucius Institute. Many others do in practice arrange for alternative engagement with China, even if they do not say this in the same statement in which they announce the closure of the Confucius Institute.

The University of Massachusetts Boston called for “a new model, a different arrangement,” in an announcement of Confucius Institute’s closure sent by Interim Chancellor Katherine Newman and Provost Emily McDermott to the “University of Massachusetts Boston Community.” Newman and McDermott added that they hoped to maintain pieces of the Confucius Institute under a new name: “We have been in conversations with Renmin University in Beijing about ways to continue some of the Confucius Institute’s activities through our standing university-to-university partnership with them.”61

The University of Michigan sought to develop new partnerships with Hanban. In a public statement, the university announced, “U-M is in communication with Hanban, exploring alternative ways to support the greater U-M community to continuously engage with Chinese artistic culture.” 62 In a letter to Hanban, Vice Provost James Holloway pitched Hanban on the idea of “a new model for collaboration between the UM and Hanban,” and listed a number of programs and schools Hanban could “engage with.”63 (For a more detailed profile of the University of Michigan, see “Replace the CI.”)

The University of Nebraska Lincoln hoped “that this is only a new phase in the partnership between UNL and XITU,” an acronym for Xi`an Jiaotong University, its Confucius Institute partner. This letter, from Chancellor Ronnie D. Green to Wang Shuguo, urged a new agreement in time to keep the Confucius Institute teachers on campus.64

In a letter to Hanban, University of Oregon Dean Dennis Galvin described a “commitment, in a post Confucius Institute era, to maintain and indeed expand” partnerships with East China Normal University.65

The University of Tennessee Knoxville lauded its CI for “laying the groundwork for a strong partnership with Southeast University” on which it intended to build further joint programs.66

Central Connecticut State University President Zelma R. Toro hoped that “once conditions permit,” CCSU and Shandong Normal University would one day be able to “develop new collaborative programs.” In the meantime, she wrote to Shandong President Zeng Qingliang, “Please be assured that CCSU will continue to work bilaterally with Shandong Normal University… in accordance with our Memorandum of Understanding signed in 2007.”67

The University of Wisconsin-Platteville (one of the few that also cited national security concerns) told CIEF and CLEC it intended to close the Confucius Institute “in an amicable and respectful manner so that our partnership can continue many other important programs, projects, and engagements.” Chancellor Dennis J. Shields specifically cited the Master of Science in Teaching English as a Second Language program as one he hoped to continue jointly with CIEF and CLEC, “as well as other programs and projects in the future.”68

Some institutions apparently prepared in advance for their Confucius Institutes’ closure, having already begun negotiating replacement agreements to continue parts of the Confucius Institute program. Colorado State University stated that “A new agreement will be formalized with Hunan University to continue Chinese language and cultural exchange at CSU.”69 Richard Benson, president of the University of Texas Dallas, wrote that “We will be arranging a new bilateral agreement with Southeast University to continue our mutually beneficial engagements.”70 Benson went on to describe the “newly created UT Dallas Center for Chinese Studies” which would house many of the programs the Confucius Institute once ran. (Indeed, the former director of the Confucius Institute heads this new center.)

Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and its Chinese partner university, Sun Yat-sen University had built a number of partnerships outside of the Confucius Institute—with “nearly every school at IUPUI collaborating with SYSU over the course of our affiliation,” IUPUI Chancellor Nasser H. Paydar wrote to Sun Yat-sen University President Jun Luo. Paydar assured Luo that the closure of the Confucius Institute “has no influence over IUPUI’s commitment to the strategic alliance between our institutions.” In the absence of the Confucius Institute, Paydar promised to work “with you and your colleagues at SYSU to explore opportunities to continue to advance the study of Chinese language and culture, building on the legacy of our valued partnership.”71

U.S. Public Policy

Thirty-three institutions blamed U.S. public policy for the closure of a Confucius Institute. In a 2020 letter to Hanban director general Ma Jianfei, University of North Carolina Charlotte’s Interim Chancellor Joan F. Lorden detailed the ways state and federal government officials can influence a university’s decision:

Over the last two years alone, countless hours have been spent responding to inquiries regarding the Institute, including inquiries from members of the local and national media, the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on Global Human Rights, the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, and numerous concerned state and local legislators and citizens. As you are likely aware, there are also several legislative efforts that preclude UNC Charlotte from maintaining its Confucius Institute. Since 2019, the National Defense Authorization Act has prohibited UNC Charlotte from receiving language program funding from the U.S. Defense Department due to the presence of the Institute, and there is additional pending federal legislation that could result in substantial consequences for the university unless we terminate the Agreement. More recently, legislation was introduced in the North Carolina General Assembly that would prohibit any constituent institution of the University of North Carolina, including UNC Charlotte, from operating a Confucius Institute as soon as the start of this academic year, and render private colleges and universities with a Confucius Institute ineligible to receive scholarship funds from the State of North Carolina. UNC Charlotte must be as prepared as possible for the potential impact of this legislation.72

Valparaiso University President José D. Padilla likewise spelled out the power of U.S. public policy in this public statement from 2021:

First, some members of Congress reached out to the University in 2020 and earlier in 2021, questioning the presence of CIVU [Confucius Institute at Valparaiso University]. A federal law, the National Defense Authorization Act, already prohibits the Defense Department (DOD) from funding research at any university with a Confucius Institute. DOD funding is not the only federal funding at risk, Department of Education (DOE) funding may also be. Just this past March, DOE funding and Confucius Institutes were intertwined in a bill, S.590, which the U.S. Senate passed by unanimous consent. (Unanimous consent means that no U.S. Senator objected to this bill.) This bill would impose tight restrictions on funding from DOE (other than student financial aid) to colleges hosting Confucius Institutes. A potential cut-off of DOE funding would be devastating to our financial position. This is not a risk we can take.73

Padilla went on, however, to insist that although his decision followed close on the heels of an investigation by Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita, the “wave of closures [of other Confucius Institutes] and the other factors above are the reasons for my closing CIVU, not the Indiana Attorney General’s (AG) investigation into CIVU.”74

Of the 33 colleges and universities that cite public policy as a reason for the Confucius Institute’s closure, 19 cite the potential loss of federal funds. Eleven specifically cite by name the National Defense Authorization Act, which barred certain grants from the Department of Defense to colleges and universities with Confucius Institutes.

“The passage of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2019 has adversely affected the University of Maryland’s ability to both host a Confucius Institute and receive certain federal funding,” University of Maryland President Wallace D. Loh wrote to Ma Jianfei, director general of CLEC, in 2020. “Our subsequent application for a waiver from the relevant terms of this legislation was not accepted. As such, we are unfortunately unable to continue hosting the Confucius Institute at the University of Maryland.”75

San Francisco State University President Leslie E. Wong issued a statement that “The John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 specifies that Department of Defense (DoD) funds cannot be used to support a Chinese language program at an institution of higher education that hosts a Confucius Institute….San Francisco State is unable to operate both the Confucius Institute and the Chinese Flagship Program, and will close the Confucius Institute.”76

The University of Washington, one of our case studies described in greater detail later in this report, told Hanban it was “very disappointed to be forced to choose between hosting CIWA and pursuing this new opportunity” to host a Department of Defense-funded Chinese Language Flagship Program.77

Three universities cited warnings they received from the State Department. The University of New Hampshire mentioned “a series of probes/inquiries/investigations from the Justice, Education as well as the State Department.”78 University of Oklahoma spokesperson Kesha Keith told Grand Lakes News that “the U. S. Department of State conducted an inquiry into the Confucius Institute housed at OU.”79 The University of Missouri, which is reported to have violated visa rules,80 discreetly cited “guidance from the State Department.”81

Interestingly, the University of Pittsburgh did not mention the State Department, but merely said “The CI-Pitt program has experienced increasing scrutiny by U.S. federal agencies.”82 In fact one year before the CI formally closed, the university had “suspended” the CI after the State Department found that all the CI teachers scheduled to arrive at the university failed to meet visa regulations.83

Replacing Confucius Institutes with University Programs

Twenty-three universities said they would replace the Confucius Institute with their own, in-house programs. However, 13 of these 23 also said the CI would be replaced by a new partnership with a Chinese entity—suggesting that the university-run program they envisioned was actually one run in partnership with a Chinese institution, often their former CI partner.

Temple University, for example, announced it would “not receive any further direct funding from the Chinese government in connection with” the Confucius Institute, and would instead open a new Center for Chinese Language Instruction to be “funded, housed, and managed by Temple University’s Office of International Affairs.” However, in order to “offer these language courses, Temple and its College of Liberal Arts will partner with Zhejiang Normal University,” which had been Temple’s CI partner and the source of its CI teachers.84

Many universities described their new program as the culmination of the Confucius Institute. “After ten years of grant-funded support for the Confucius Institute, UTSA is now ready to graduate its China-related language and culture programs into a more robust environment, UTSA East Asia Institute,” University of Texas San Antonio Vice Provost Lisa Montoya wrote to Wang Jiaqiong of the University of International Business and Economics. Montoya added that “the Confucius Institute’s activities will transition to the East Asia Institute as of June 30, 2019.”85

North Carolina State University promised to “provide our institutional funding to continue the CI’s planned academic, cultural and service programs,” using the “infrastructure and momentum” built through the Confucius Institute.86

The University of Texas Dallas suggested to Hanban that the closure of the Confucius Institute was “in the spirit and stated intent of Article 7 [of the university’s agreement with Hanban] that the program ultimately become self-sustaining, independent of contributions from Confucius Institute Headquarters.”87

Ten of the 23 institutions announced plans to develop their own replacement programs without announcing, at the same time, plans to develop new partnerships with Chinese institutions: Chicago Public Schools, Pace University, Purdue University, the University of Akron, the University of Idaho, the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign, the University of North Carolina Charlotte, the University of Miami Ohio, and the University of Montana.

Yet, at least four of these (University of Idaho, University of Illinois Urbana Champaign, University of Montana, and Purdue University) did in fact operate these programs in partnership with their former CI partner. (We offer further analysis in the section “What Happens After a CI Closure” as well as a chart in Appendix I.)

Expense

Nine colleges and universities said the Confucius Institute was too expensive—a reason that surprised us, given that the Chinese government typically funds most costs associated with a CI. The Chinese government typically asks host universities to cover fifty percent of the Confucius Institute’s operating expenses, but most do so by offering classroom and office space and other in-kind contributions.

“Due to the budget situation in Alaska,” University of Alaska Anchorage Chancellor Cathy Sandeen informed Hanban that it would close the Confucius Institute.88 At the time, the university was preparing for a 41 percent budget cut precipitated by decreased state oil revenue.89

University of Iowa President J. Bruce Harreld blamed “a twenty-year disinvestment in public higher education by the State of Iowa and back-to back budget cuts by the Iowa legislature.” In his letter to Hanban, President Harreld added, “If we could find a way without university funding to continue to provide the valuable outreach activities that our Cl has undertaken over the past twelve years, we would do so.”90

Too Few Students

Seven institutions said the Confucius Institute attracted too few students. “Goals were set at the beginning of the contract and, unfortunately, we have not met them through the CI partnership,” University of West Florida President Martha D. Saunders wrote to Jing Wei of Hanban in 2017. She said “very few UWF students” had participated in trips to China and there was “limited demand” for Confucius Institute classes.91

“Declining enrollment in the program has made it difficult to continue its support,” Miami Dade College Interim President Rolando Montoya wrote to Hanban in 2019.92 “We have seen a decline in student enrollment in Mandarin coursework,” University of South Florida System Vice President Roger Brindley wrote to Hanban in 2018.93

Reorganization of Hanban

Seven institutions blamed the reorganization of Hanban, which renamed itself the Center for Language Exchange and Cooperation and split off a separate nonprofit, the Chinese International Education Foundation, to manage Confucius Institutes.

“The University of Southern Maine does not consent to this change and therefore declines to accept the transfer of the brands of Confucius Institute and Confucius Classroom to The Foundation,” President Glenn Cummings and Provost Jeannine Diddle wrote to Yang Wei of the Chinese International Education Foundation and Ma Jianfei of the Center for Language Education and Cooperation.94

The Colorado State University Office of the General Counsel wrote to Hunan University that “Due to the deregistration of the organization, CSU has decided to terminate any agreements affiliated with the Confucius Institute Headquarters of China.”95

COVID-19

Six universities blamed the COVID-19 pandemic for precipitating the closure of a Confucius Institute.

“The Covid-19 pandemic has significantly impacted Central Connecticut State University's (CCSU) Confucius Institute’s (CI) ability to conduct its programming, much of which relies on international travel to and from the United States and China,” President Zulma Torro explained to Hao Pan of CLEC.96

UCLA wrote in an email to NAS that “there was an urgency to focus the university’s resources and expertise on pressing world issues, such as the climate crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.”97

Transferring the Confucius Institute

Six universities said they intended to find a new home for the CI by transferring it elsewhere: Pfeiffer University, San Diego State University, the University of Maryland, the University of Arizona, the University of Washington, and Western Kentucky University. It is unclear if the University of Maryland did find a new host for its CI, but the other four did, as described in the section “What Happens After a CI Closure.”

University of Washington Vice Provost Jeffrey Riedinger told Hanban that “I am personally leading efforts to identify an appropriate alternate host institution.”98

“It was always our plan to find alternative solutions to keep the K-12 program alive,” Western Kentucky University President Timothy Caboi told the CI Headquarters. “We are pleased to inform you that the Simpson County Board of Education has agreed to be the new host site for the program.”99

San Diego State University told Hanban its program was “sufficiently mature that it deserves continued development within the school system here in San Diego County.” President Adela de la Torre wrote, “We are delighted that you have accepted our recommendation to transfer our existing CI education initiatives and services to a local educational partner independent from SDSU.”100

Concern about the Chinese Government

Despite widespread public concern about the Chinese government’s ulterior motives for supporting Confucius Institutes, only five universities referenced these concerns.

Two laid out possible problems with Chinese government interference, but concluded this had not been the case at their university.

University of Wisconsin-Platteville Chancellor Dennis J. Shields gave to CLEC and CIEF an overview of various concerns that have circulated:

Over the past two years, the United States of America and its Department of State have raised serious concerns as to the scope of the People’s Republic of China and Beijing’s influence over higher education institutions, both nationally and globally.... Unfortunately, due to these recent and continued concerns raised by the United States federal government and public officials as well as the recently enacted legislation, I have reached the difficult decision to end the UW-Platteville Confucius Institute.101

Shields was adamant, though, that the University of Wisconsin had good experiences with Hanban: “I stress that UW-Platteville’s relationship with the Confucius Institute and SCUN has been positive, transparent, and engaging.” Shields added that “My hope is that we can work together to make this change in an amicable and respectful manner so that our partnership can continue many other important programs, projects, and engagements.”102

University of South Florida System Vice President Roger Brindley wrote to Hanban that “USF is increasingly troubled by these concerning national reports.” Brindley emphasized that “the USF CI has operated with a high degree of integrity and professionalism at all times,” though “CI’s at other universities in the United States have come under increased and persistent scrutiny by elected government officials.”103

Northwest Nazarene University, however, said with apparently genuine concern, “We made this decision because of broad national security concerns and legislation that was pending at that time.”104

Texas A&M and Prairie View A&M both closed their Confucius Institutes after a single decision by the Texas A&M System Chancellor John Sharp. Sharp gave a concise statement to The Dallas News, citing a letter Texas A&M received from two Texas Congressmen, Republican Michael McCaul and Democrat Henry Cuellar. “They have access to classified information we do not have. We are terminating the contract as they suggested,” Sharp said.105

Despite Chancellor Sharp’s concerns, Texas A&M President Michael K. Young promptly wrote to A&M Chinese partner, Ocean University, assuring them that “I believe, and hope you will agree, that the partnership between our two great universities is broader and deeper than any one grant alone.” Young added that he was “committed” to “continued enhancements of our research collaborations” and that he believed “even more collaborations will be forged and our partnership will be stronger.”106

Other Reasons

Thirteen universities gave reasons unique and therefore uncategorized—but most of them are extremely vague.

The University of North Florida issued a statement claiming that “After reviewing the classes, activities and events sponsored over the past four years and comparing them with the mission and goals of the University, it was determined that they weren’t aligned.”107

Kennesaw State University, in an internal announcement, said it was “realigning its global focus to its current strategic priorities.”108

A few, however, are notable. The University of Chicago closed its Confucius Institute in 2014, following a showdown with Hanban Director General Xu Lin, described in greater detail above. The university issued a public statement announcing the closure of the Confucius Institute, explaining that “Recently published comments about UChicago in an article about the director-general of Hanban are incompatible with a continued equal partnership.”109

Kansas State University terminated its Confucius Institute in 2019 and promptly invited Hanban to renegotiate. “This termination shall become effective June 12, 2019,” Provost and Executive Vice President Charles S. Taber wrote to Hanban on December 11, 2018. But “if we can reach mutually acceptable terms,” Taber wrote, the university would “consider entering into separate, new agreements related to a Confucius Institute.” He invited Hanban to “Please contact Grant Chapman, Associate Provost for International Programs,” to discuss the possibilities.110 In fall 2019, Chapman did reach out to Hanban with a proposed revised contract for a Confucius Institute.111 But in February 2020, Taber again wrote to Hanban, noting without explanation that “Kansas State University has decided not to continue to pursue new agreements related to a Confucius Institute at the University at this time.”112

Clark County School District, one of the few K-12 hosts of a Confucius Institute rather than a Confucius Classroom, told us by phone it had withdrawn unwillingly from the Confucius Institute, because “The main reason was we were not able to get licensable teachers to teach Chinese in Nevada.”113 At the time, Clark County hoped to resume bringing Hanban teachers from China, suggesting this Confucius Institute closure could have been temporary. In 2020, however, Chief Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment Officer Brenda Larsen-Mitchell wrote to Hanban that the school district “will be withdrawing from the Confucius Institute Program,” though she did not give a reason.114

Response from China

We tracked the responses colleges and universities received from Chinese institutions reacting to news that the Confucius Institute would close. Of the 104 CIs that have closed, we were able to collect responses to 44. In 27 cases, Hanban/CLEC/CIEF responded; in 9 cases, Chinese universities responded. Both Hanban and a Chinese university responded in 8 instances.

Some universities denied that Hanban or their Chinese partner university ever responded to the announcement that the CI would close. Others did not provide documents in time for publication. In Appendix III, we print excerpts from all the responses we know about. The original documents are available in our online database at https://data.nas.org/confucius_institute_contracts.

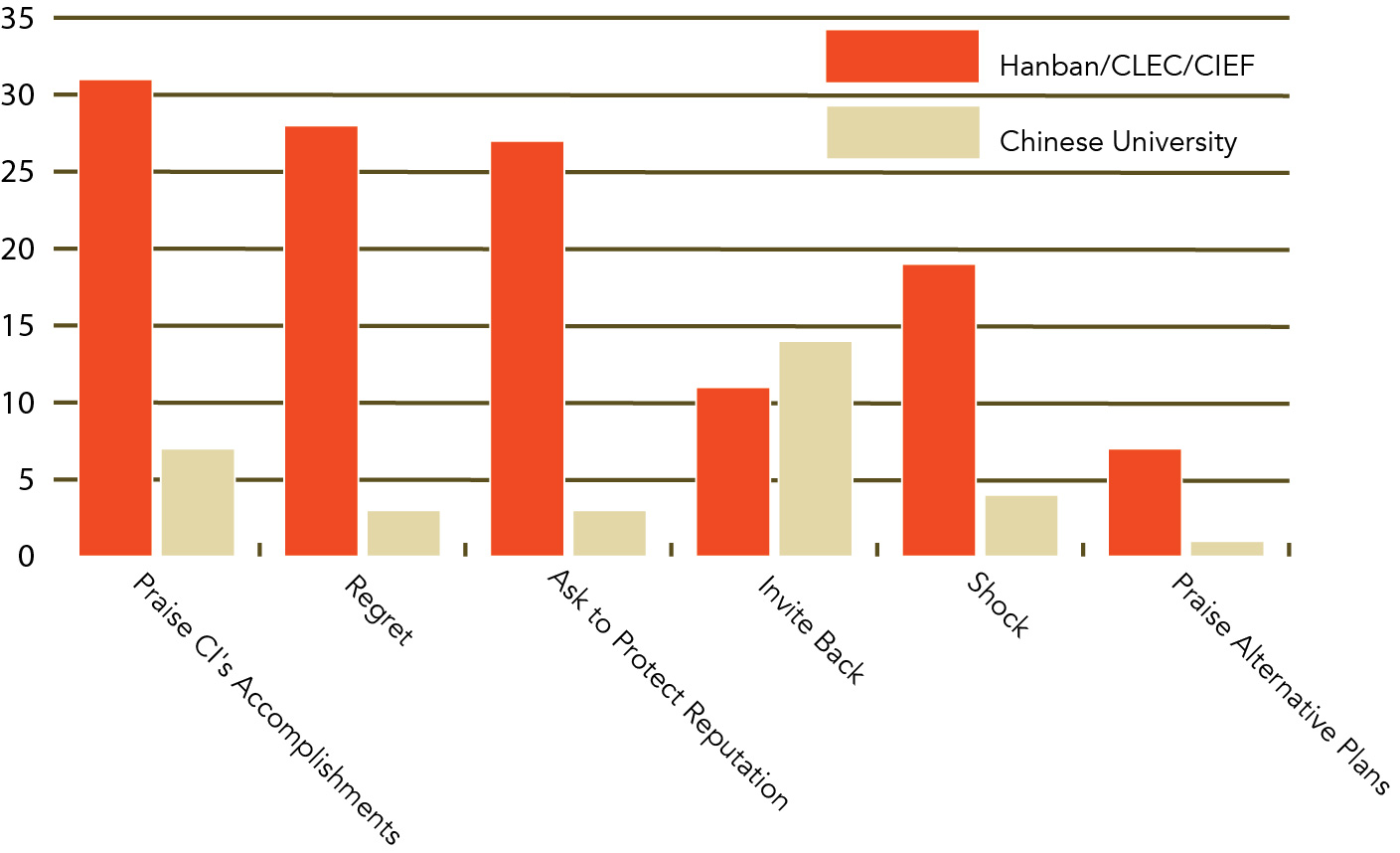

We organized these responses into six categories: praising the CI’s accomplishments (Hanban 31; Chinese university 8); expressing regret (Hanban 28; Chinese university 3); asking the university to protect the CI’s reputation (Hanban 27; Chinese university 3); inviting the university back to CI or similar programs (Hanban 11; Chinese university 14); expressing shock (Hanban 19; Chinese university 4); and praising CI alternatives the university had mentioned (Hanban 7; Chinese university 1). (Most of the responses contain several of these seven elements; these have been counted more than once.)

The following chart shows the most common responses from Hanban/CLEC/CIEF and from Chinese universities.

Response to Confucius Institute Closures

What the chart cannot show, though, is the shift in the Chinese government’s reaction over time. Responses from Hanban were initially characterized by shock and indignation, then by mere regret, and finally by well-coordinated efforts to woo colleges and universities into new partnerships. In the following section, we first examine this shift, and then turn to the remaining reactions from Chinese institutions.

Shock