The National Association of Scholars (NAS) has analyzed college common readings since 2010. Different college readings have risen and fallen in popularity—Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks one year, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me another—but our overall critique has remained constant. College common reading committees overwhelmingly select a narrow range of books: politically progressive, designed to promote activism, confined to American authors, literarily mediocre, juvenile, recent, and mostly nonfiction.

The limitations of college common reading selections derive from their institutional frameworks. Non-academic mission statements steer selection committees away from intellectually challenging books toward those promoting progressive beliefs or activism; the selection committees are usually run or dominated by activist “co-curricular” administrators rather than professors; and common reading programs are frequently integrated with programs of service-learning and civic engagement, which are designed to promote student activism rather than to educate. We advocate systematic reform of college common reading programs. We also advocate external supervision of common reading programs at public universities, to guarantee their intellectual diversity.1

Last year we presented and analyzed information on 4,754 assignments between 2007 and 2017 at 732 separate institutions, including 1,664 individual texts.2 For 2018-2019, we provide information on 518 new college common reading selections at 475 institutions.

Last year we modified our critique of college common reading programs, shifting from an emphasis on Do differently! to an emphasis on Follow the best practices of your field! This year we have added two sections of practical advice for working within the system as it currently exists. One section provides advice for authors wishing to market their books to common reading selection committees; the second provides advice for selection committee members who want to persuade their colleagues to choose classic books. While we still call for thoroughgoing reform of common reading programs, we believe these new sections will forward useful, if marginal, reforms within the current system.

We have organized Beach Books 2018-2019 in the following sections:

- our introductory essay summarizing the report;

- our analysis of the 2018-2019 selections;

- our advice to would-be authors and to selection committee members; and

- our Appendices with our full data, including an expanded list of 150 books the NAS recommends for colleges and universities with common reading programs.

The printed version of Beach Books 2018-2010 does not include our appendices. These appendices appear in on our website—https://nas.org/reports/beach-books19.

Introduction

Common reading programs still overwhelmingly select a narrow range of books: politically progressive, designed to promote activism, confined to American authors, literarily mediocre, juvenile, recent, and mostly nonfiction. The predilections of committee members are hardwired by mission statements that require committee members to choose books of this sort. Common reading programs run by co-curricular administrators, such as Offices of Student Life, Sustainability, and Diversity, usually skew even further toward choosing progressive propaganda. Common reading programs in 2018 are much as they were in 2010, when the National Association of Scholars began analyzing common readings.

The five most frequently assigned common readings of 2018 illustrate perfectly the failings of common reading programs. Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption (18 selections), a pedestrian memoir that argues that America’s criminal justice system is fundamentally corrupted by racism and propagandizes its readers to join “social justice organizations” working to release criminals from jail, continues as the most popular single common reading. Jennine Capó Crucet’s Make Your Home Among Strangers (12 selections) encourages students to think of themselves in terms of ethnic identity groups. Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (11 selections) propagandizes for universal government-provided health care.3 Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me (10 selections) preaches hatred of whites. Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give (10 selections) is a Black Lives Matter young adult novel. These five most frequently assigned common readings were all published since 2010; four are about African Americans, one about a Hispanic American, and all encourage racial division and resentment.

Yet 2018’s common readings include small but noticeable improvements over 2017’s. In 2017, 24 common readings dated from before 1980, including 10 from before 1900. In 2018, 38 common readings dated from before 1980, including 15 from before 1900. Thirty-eight remains a small fraction (7%) of the total of 518 assignments this year—but enough to give hope for further improvement.

Notable individual assignments included Homer’s The Odyssey (Luther College), Henry Brooks Adams’s Democracy: An American Novel (Arizona State University, School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership), and W. E. B. DuBois’s The Souls of Black Folks (Carthage College). In the 11 years between 2007 and 2017, 11 colleges assigned Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; in 2018 alone, five colleges assigned Shelley’s novel. Several colleges paid attention to local classics: the University of Central Florida assigned Zora Neale Hurston’s Dust Tracks on a Road, University of Nebraska Omaha assigned Willa Cather’s My Ántonia, and the University of Mississippi assigned selections from William Faulkner’s Collected Stories. The common readings this year are perceptibly better than last years.

At the same time, common readings have become slightly less homogenous. In 2017, 21% of assignments fell into the category Civil Rights/Racism/Slavery, 16% into the category Crime and Punishment/Police, and 25% into African American; this year the corresponding numbers are 19%, 15%, and 25%. This still represents a sizeable increase in homogeneity since 2014, when the corresponding numbers were only 11%, 10%, and 16%, but it suggests a tentative trend toward greater intellectual diversity in college common readings.

These small improvements warrant a shift in focus this year. In previous years we have made a series of recommendations for thorough reform of common reading programs, including changing their mission statements to focus exclusively on academic goals, staffing the selection committees entirely with professors and librarians, and instituting external oversight of common reading selection committees at state universities. We stand by these recommendations. Yet we also want to improve within the current system. The current system will never reliably select good common readings, but it can be made to reduce homogeneity and to select a larger minority of good readings.

This year we add advice to would-be common reading authors on how to market their books to common reading selection committees. This includes practical tips such as Set up a booth at the First Year Experience Conference and Charge less to visit a campus than Ta-Nehisi Coates or Bryan Stevenson. The worst common reading books are frequently the most popular ones, such as Just Mercy and Between the World and Me. Increasing the number of common reading authors should reduce the homogeneity of common reading selections and marginally improve their quality.

We also add advice to members of common reading selection committees who are trying to persuade their colleagues to choose classic books. This is an uphill struggle, and we are trying to help this minority to frame their arguments most persuasively. Even if only a few succeed, we might increase the proportion of classic common reading selections—books published before 1980—to 10%.

Both our pieces of advice are first drafts. We would welcome suggestions for improvement, from common reading authors, members of selection committees, and anyone with useful knowledge to share. We would also welcome suggestions for other sorts of advice we might provide.

Beach Books has three audiences. For common reading selection committee members who do not agree with our recommendations, we provide raw data that we hope they will find useful. For common reading selection committee members who do agree with our recommendations, we provide practical advice for ways to make marginal improvements within the current system. For the broader public of education reformers, we provide a vision of what a college common reading should be.

Our Beach Books reports encapsulate the National Association of Scholars’ mission as a whole—collegiality toward status quo academics, practical advice for reformers, and a vision of higher education as it should be for the country as a whole.

Methods

What We Included

Our data includes common readings for every college and university we could find that have such programs—including readings for sub-units of an institution such as honors colleges. We included books assigned as summer readings, whether to freshmen or to all students. Generally, these books are outside the regular curriculum, but a few of them are tied to first-year courses.

How We Categorized the Institutions and Programs

Each common reading program is categorized by Institution Name, State, Type of Institution, Top Ranking, Program Name, Intended Audience, and Author Visit.

We classify each college and university by Type—public, private sectarian, private nonsectarian, and community colleges. We also see whether they are ranked by U.S. News & World Report among either the top 100 National Universities or the top 100 National Liberal Arts Colleges. We have attempted to be comprehensive, although we have undoubtedly missed a few programs. We would be grateful for the names of common reading programs we have missed, so we may include them in our next report.

How We Categorized the Books

Each book is categorized by Author, Title, Publication Date, Genre, Publisher, First Subject Category, Second Subject Category, First Theme, and Second Theme. We include up to two subject categories and two themes for each book, as a way to be more precise in our description of the common readings.

Inevitably such categorization lacks nuance: we categorize Richard Blanco’s The Prince of Los Cocuyos: A Miami Childhood under Artists’ Lives/Arts and Ethnic Identity/Sexual Identity, when Immigration or Coming of Age would be perfectly plausible substitutes. It also flattens works: We put Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale under Family Dysfunction/ Separation, which is accurate, but would strike most readers of Shakespeare’s late romance as falling short of capturing a play that depicts raging jealousy, biting regret, and the sweep of time. Our subject categories are meaningful, but limited. Draw conclusions from them with a grain of salt.

Subject Category defines what the book is explicitly about. Theme notes aspects of the book that we take to have been of interest to the selection committees or are of interest to us. For example, selection committees place great emphasis on diversity as a euphemism for mentioning various non-white ethnic groups at home or abroad; we have therefore identified a number of ethnic, geographic, and religious subject matters as themes. Selection committees do not explicitly state their interest in whether a work is in the graphic medium, has a film or TV adaptation, or has an association with NPR, but we think these are significant facts that ought to be noted, and so we have included them as well.

Our subject categories largely overlap those of previous years, but with some alterations. We have limited our total number of subject categories to 30.

Common Readings, 2018-2019

Institutions

Beach Books 2018-2019 collects data on 518 college common reading selections in 2018-2019 at 475 institutions. These 475 institutions are located in 47 states and the District of Columbia—every part of the Union save Hawaii, New Mexico, and Wyoming.

| State | Number of Institutions |

|---|---|

| Alabama | 5 |

| Alaska | 3 |

| Arizona | 3 |

| Arkansas | 4 |

| California | 45 |

| Colorado | 7 |

| Connecticut | 8 |

| Delaware | 1 |

| District of Columbia | 5 |

| Florida | 15 |

| Georgia | 7 |

| Idaho | 3 |

| Illinois | 13 |

| Indiana | 10 |

| Iowa | 11 |

| Kansas | 6 |

| Kentucky | 7 |

| Louisiana | 6 |

| Maine | 4 |

| Maryland | 9 |

| Massachusetts | 27 |

| Michigan | 17 |

| Minnesota | 7 |

| Mississippi | 4 |

| Montana | 3 |

| Missouri | 3 |

| Nebraska | 3 |

| Nevada | 2 |

| New Hampshire | 1 |

| New Jersey | 15 |

| New York | 42 |

| North Carolina | 25 |

| North Dakota | 1 |

| Ohio | 16 |

| Oklahoma | 3 |

| Oregon | 4 |

| Pennsylvania | 34 |

| Rhode Island | 5 |

| South Carolina | 8 |

| South Dakota | 3 |

| Tennessee | 6 |

| Texas | 27 |

| Utah | 3 |

| Vermont | 5 |

| Virginia | 14 |

| Washington | 9 |

| West Virginia | 2 |

| Wisconsin |

11 |

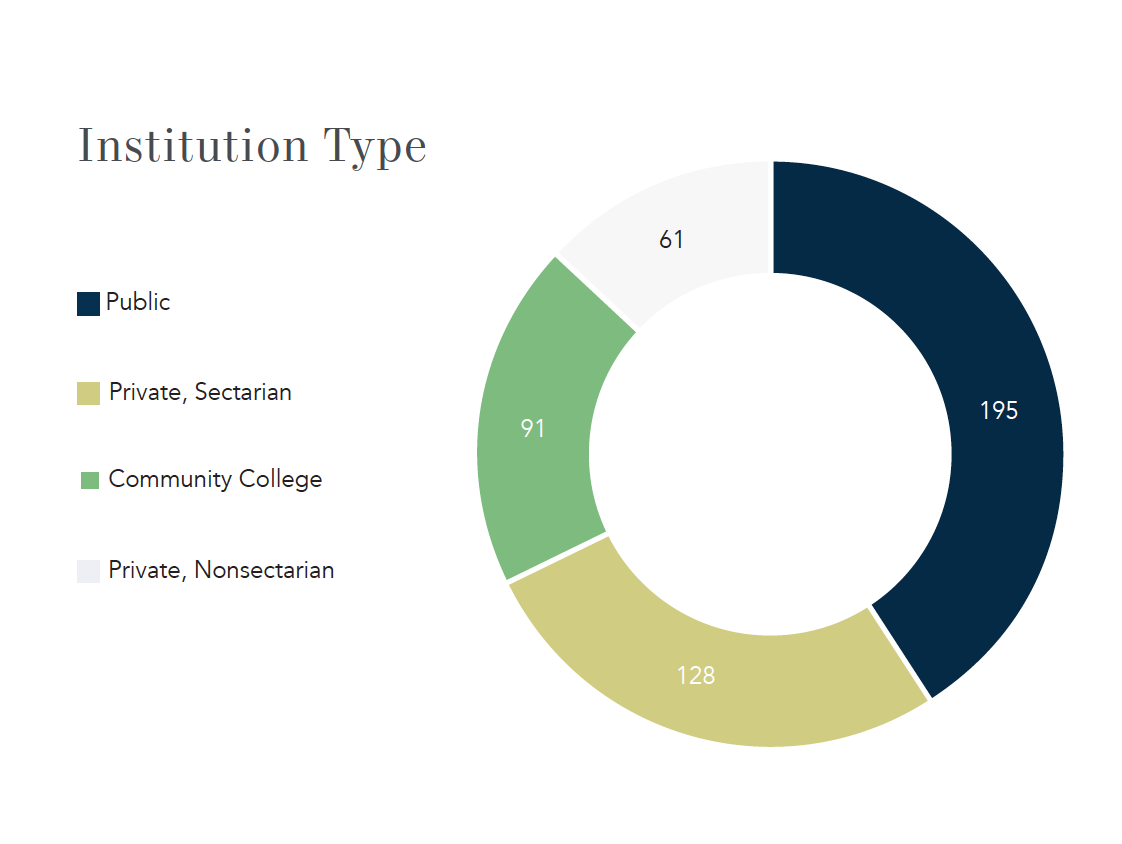

These 475 institutions include 195 public four-year institutions, 128 private sectarian institutions, 91 private non-sectarian institutions, and 61 community colleges.

According to the U.S. News & World Report rankings, these 475 institutions include nearly two-thirds of the top 100 universities in the nation and one-third of the top 100 liberal arts colleges.4

| Rankings Type | Number of Institutions |

|---|---|

| Top 100 Universities | 64 |

| Top 100 Liberal Arts Colleges Selections | 33 |

Common readings selected at the highest-ranked colleges and universities (by U.S. News & World Report ranking) are somewhat better than the typical common reading selection—especially at the top universities. Below are the assignments at the ten highest-ranked universities and liberal arts colleges with common reading programs.

Assignments

Publication Dates

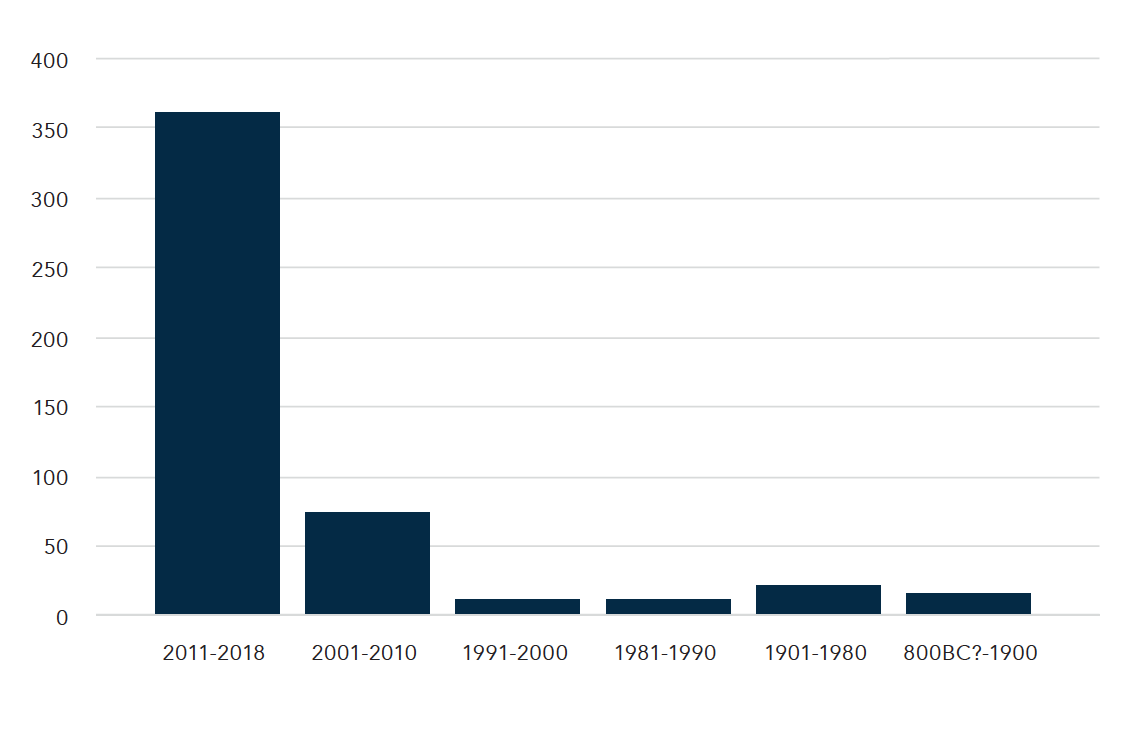

Common reading committees continue to select almost nothing but books written in the lifetimes of incoming students—and very largely books written since 2010. Out of 502 datable texts selected for 2018–2019 common readings, 366 (73%) were published between 2011 and 2018, and 440 (88%) have been published between 2001 and the present. The median publication year was 2015. The most common years of publication were 2016 (91 books, 18% of the total), 2017 (80 books, 16% of the total), and 2015 (65 books, 13% of the total).

23 selections were published in 2018—more than the 15 (3%) that were published before 1900.

The entire list of 38 common reading selections in 2018-2019 published from antiquity through 1980 appears below:

| The Iliad (Books 1-6) | Homer | Ca. 800 BC | Columbia University |

| The Odyssey | Homer | Ca. 800 BC | Luther College |

| Nicomachean Ethics | Aristotle | Ca. 350 BC | Hillsdale College |

| Ecclesiastes | Anonymous | Ca. 300 BC | The King’s College |

| Macbeth | Shakespeare, William | 1606 | The King’s College |

| The Federalist, Essays #62 and #63 | Madison, James | 1788 | Arizona State University, School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership |

| Frankenstein | Shelley, Mary | 1818 | Colorado College |

| Frankenstein | Shelley, Mary | 1818 | Corning Community College |

| Frankenstein | Shelley, Mary | 1818 | Hiram College |

| Frankenstein | Shelley, Mary | 1818 | Illinois Central College |

| Frankenstein | Shelley, Mary | 1818 | MassBay Community College |

| Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave | Douglass, Frederick | 1845 | Assumption College |

| Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl | Jacobs, Harriet | 1861 | New York University, Gallatin School of Individualized Study |

| Democracy: An American Novel | Adams, Henry Brooks | 1880 | Arizona State University, School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership |

| Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde | Stevenson, Robert Louis | 1886 | Mansfield University of Pennsylvania |

| The Souls of Black Folk | DuBois, W. E. B. | 1903 | Carthage College |

| The Machine Stops | Forster, E. M. | 1909 | DePauw University |

| My Ántonia | Cather, Willa | 1918 | University of Nebraska Omaha |

| The Bridge of San Luis Rey | Wilder, Thornton | 1927 | University of Pennsylvania |

| The Epic of American Civilization | Orozco, José Clemente | 1934 | Dartmouth College |

| Grapes of Wrath | Steinbeck, John | 1939 | University of California, Santa Cruz, Rachel Carson College |

| Their Finest Hour | Churchill, Winston | 1940 | Catawba College |

| Under the Sea Wind: A Naturalist's Picture of Ocean Life | Carson, Rachel | 1941 | University of California, Santa Cruz, Rachel Carson College |

| How to Mark a Book | Adler, Mortimer | 1941 | University of California, Santa Cruz, Stevenson College |

| Dust Tracks on a Road | Hurston, Zora Neale | 1942 | University of Central Florida |

| Hiroshima | Hersey, John | 1946 | Florida College |

| Hiroshima | Hersey, John | 1946 | Moravian College |

| Existentialism Is a Humanism | Sartre, Jean-Paul | 1946 | University of California, Santa Cruz, Stevenson College |

| 1984 | Orwell, George | 1949 | Lone Star College, Kingwood |

| 1984 | Orwell, George | 1949 | Somerset Community College |

| Collected Stories | Faulkner, William | 1950 | University of Mississippi |

| Mere Christianity | Lewis, C. S. | 1952 | Harding University |

| Sonny’s Blues | Baldwin, James | 1957 | Le Moyne College |

| The Fire Next Time | Baldwin, James | 1962 | Loyola University Maryland |

| The Left Hand of Darkness | LeGuin, Ursula K. | 1969 | Los Angeles Valley College |

| The Girl Who Was Plugged In | Tiptree, James, Jr. [Alice Bradley Sheldon] | 1974 | University of California, Santa Cruz, Crown College |

| Getting Out | Norman, Marsha | 1978 | Owensboro Community and Technical College |

| Kindred | Butler, Octavia | 1979 | University of Maryland, Baltimore County |

Genres

We classify common readings by genre: biography, memoir, newspaper, nonfiction, novel, play, poetry, and so on. The vast majority of the 507 classifiable assignments were in the three allied genres of Nonfiction (178, 35% of the total), Memoir (135, 27% of the total), and Biography (21, 4% of the total). Together there were 334 selections from these three genres, 66% of the total number of assignments.

Novels were the most popular genre of imaginative literature: 128 selections, 25% of the total.

| Genre | Number of Assignments |

|---|---|

| Article | 7 |

| Biography | 21 |

| Comic Book | 1 |

| Epic Poem | 1 |

| Essay | 5 |

| Film | 2 |

| Memoir | 135 |

| Mural | 1 |

| Musical | 2 |

| Newspaper | 1 |

| Nonfiction | 178 |

| Novel | 128 |

| Play | 5 |

| Podcast | 1 |

| Poetry | 4 |

| Short Stories | 12 |

| Speech | 1 |

| Workbook | 1 |

| Total | 507 |

Subject Categories

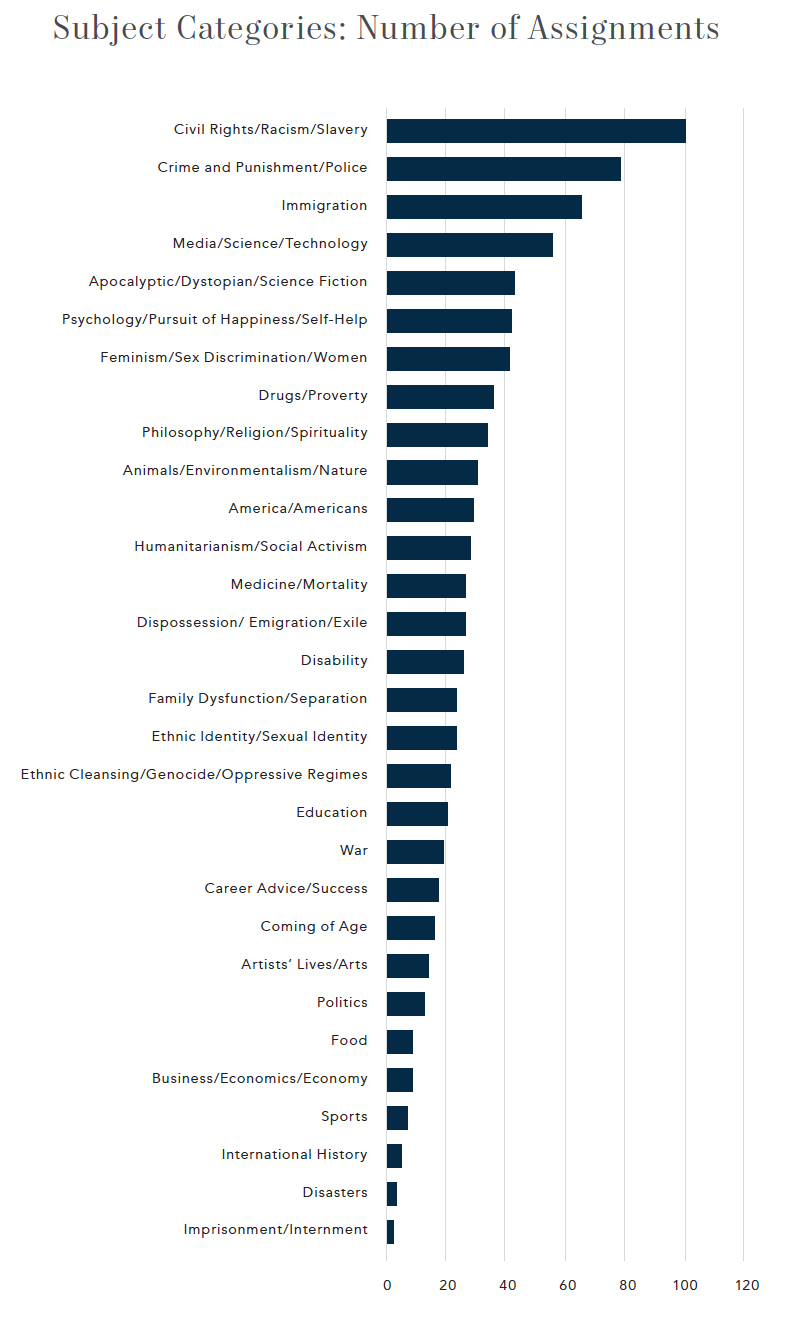

We divided the common readings into 30 subject categories. Since each book could be assigned up to two categories, the total number of subject categories is greater than the number of assignments. In 2018-2019, there were 848 assigned subject categories. A book such as Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give (2017) was categorized under Civil Rights/Racism/Slavery and Crime and Punishment/Police; Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West (2017) was categorized under Dispossession/Emigration/Exile and Immigration.

The most popular subject categories in 2018-2019 were Civil Rights/Racism/Slavery (100 readings), Crime and Punishment/Police (78 readings), Immigration (65 readings), Media/Science/Technology (55 readings), and Apocalyptic/Dystopian/Science Fiction (42 readings).

| Subject Category | Number of Selections |

|---|---|

| America/Americans | 29 |

| Animals/environmentalism/Nature | 30 |

| Apocalyptic/Dystopian/Science Fiction | 42 |

| Artists' Lives/Arts | 13 |

| Business/Economics/Economy | 8 |

| Career Advice/Success | 18 |

| Civil Rights/Racism/Slavery | 100 |

| Coming of Age | 15 |

| Crime and Punishment/Politics | 78 |

| Disability/Disease/Mental Health | 25 |

| Disasters | 3 |

| Dispossession/Emigration/Exile | 26 |

| Drugs/Poverty | 35 |

| Education | 20 |

| Ethnic Cleansing/Genocide/Oppressive Regimes | 21 |

| Ethnic Identity/Sexual Identity | 23 |

| Family Dysfunction/Separation | 23 |

| Feminism/Sex Discrimination/Women | 40 |

| Food | 8 |

| Humanitarianism/Social Activism | 28 |

| Immigration | 65 |

| Imprisonment/Internment | 2 |

| International History | 4 |

| Media/Science/Technology | 55 |

| Medicine/Mortality | 26 |

| Philosophy/Religion/Spirituality | 33 |

| Politics | 12 |

| Psychology/Pursuit of happiness/Self-Help | 41 |

| Sports | 6 |

| War | 19 |

| Total | 848 |

Themes

We have also recorded 22 further themes prominent among these assignments. Each book could be assigned up to two themes. We assigned Joshua Davis’ Spare Parts: Four Undocumented Teenagers, One Ugly Robot, and the Battle for the American Dream (2014) the themes Latin American and Protagonist Under 18, while we could have substituted Film/TV version exists as one of those themes.

In 2018–2019, there were 352 assigned themes. Most of these register the persisting interest in diversity, defined by non-white ethnicity at home and abroad, but the remainder register other aspects of common readings worth noting. Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000) has an Islamic World theme and a Graphic work theme; Reyna Grande’s The Distance Between Us (2012) has a Latin American theme and a Protagonist Under 18 theme. Many common readings discuss books of which a film or television version exists, a significant number are graphic novels or memoirs, and many have a protagonist under 18 or are simply young-adult novels. The themes register most strongly the common reading genre’s continuing obsession with race, as well as its infantilization of its students, its middlebrow taste, and its progressive politics.

In 2018-2019, the most popular themes were African American (129), Latin American (46), African (28), Film/Television version exists (27), and Graphic work (16).

| Theme | Number of selections |

|---|---|

| Afghanistan War | 1 |

| African | 28 |

| African American | 129 |

| African Diaspora | 4 |

| Asian | 9 |

| Asian American | 11 |

| European | 15 |

| Film/Tv version exists | 27 |

| Graphic work | 16 |

| Iraq War | 2 |

| Islamic World | 13 |

| Jewish World | 4 |

| Latin American | 46 |

| Muslim American | 4 |

| Native American | 7 |

| NPR | 4 |

| Pacific islander | 1 |

| Protagonist Under 18 | 15 |

| South Asian | 5 |

| Southeast Asian | 4 |

| White Appalachian | 2 |

| Young Adult | 5 |

| Total | 352 |

Most Widely Assigned Books

These were the ten most widely assigned books in 2018-2019:

| Book, Author, year | Genre, Subject Categories | Number of Times Assigned |

|---|---|---|

| Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption Stevenson, Bryan 2014 |

Nonfiction Civil Rights/Racism/Slavery Crime and Punishment/Police African American theme |

18 |

| Make Your Home Among Strangers Crucet, Jennine Capó 2015 |

Novel Coming of Age Immigration Latin American theme |

12 |

| The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks Skloot, Rebecca 2010 |

Biography Media/Science/Technology Medicine/Mortality African American theme |

11 |

| Between the World and Me Coates, Ta-Nehisi 2015 |

Memoir Civil Rights/Racism/Slavery Crime and Punishment/Police African American theme |

10 |

| The Hate U Give Thomas, Angie 2017 |

Novel Civil Rights/Racism/Slavery Crime and Punishment/Police African American theme Film/TV version exists |

9 |

| Lab Girl Jahren, Hope 2016 |

Memoir Feminism/Sex Discrimination/Women Media/Science/Technology |

9 |

| Callings: The Purpose & Passion of Work Isay, Dave 2016 |

Memoir America/Americans |

9 |

| Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood Noah, Trevor 2016 |

Memoir Artists' Lives/Arts Civil Rights/Racism/Slavery African theme |

7 |

| Educated: A Memoir Westover, Tara 2018 |

Memoir Education Family Dysfunction/Separation |

7 |

| The Other Wes Moore: One Name, Two Fates Moore, Wes 2010 |

Memoir Crime and Punishment/Police Drugs/Poverty African American theme |

7 |

This list overlaps strongly with last year’s list of most widely assigned texts. Just Mercy was also #1 last year, while Make Your Home Among Strangers rose from #6 to #2. Other texts that were on last year’s list of most widely assigned texts include The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Between the World and Me, Callings: The Purpose and Passion of Work, and The Other Wes Moore.

Homogeneity

College common readings continue to display a lack of intellectual diversity. This is most evident in the clustering of readings on modern African-American experience, which focus especially upon African-Americans’ relationship to the criminal justice system. This clustering is driven significantly by the most widely assigned texts. We classified three of the top five texts with the subject categories Civil Rights/Racism/Slavery and Crime and Punishment/Police and an African American theme. This concentration has slightly decreased this year, after a spike in the last several years, but still remains significant among the proportion in common readings as recently as the year 2014/2015.5

| Subject Categories | 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Civil Rights/Racism/Slavery | 41 (11%) | 64 (18%) | 74 (21%) | 107 (21%) | 100 (19%) |

| Crime and Punishment | 61 (16%) | 99 (27%) | 103 (29%) | 160 (32%) | 129 (25%) |

| Theme | 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American | 61 (16%) | 99 (27%) | 103 (29%) | 160 (32%) | 129 (25%) |

The percentage numbers above are “percentage of total assignments,” not “percentage of total subject categories” or “percentage of total themes.”

Predictability

The ideologically-constrained common reading genre has become so homogenous that common reading selections have become predictable.

Last year we predicted that at least five of the ten most widely assigned texts would have African American themes. We were correct: the five books in the top-ten list with African American themes were Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Between the World and Me, The Hate U Give, and The Other Wes Moore: One Name, Two Fates.

Last year we predicted that Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, Between the World and Me, and Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race would all remain in the top ten most widely assigned texts. We called two out of three: Just Mercy and Between the World and Me did, but Hidden Figures, which was only assigned at four colleges, fell off the top-ten list.

Last year we predicted that at least ten assignments would express transparent anti-Trump passion. This prediction has wiggle room, but we were probably wrong.

Last year we predicted that at least five colleges would select #MeToo-themed texts. This prediction also has wiggle room, but we were probably wrong too.

Last year we predicted that no college would assign Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos (2018) in the next three years, although it is a common reading “natural”—a bestseller that provides psychological advice. None did this year.

Last year we predicted that no college outside Nebraska would assign Ben Sasse’s The Vanishing American Adult: Our Coming-of-Age Crisis—and How to Rebuild a Culture of Self-Reliance (2017) in the next three years, although it is a thoughtful discussion by an eminent politician about how American youth should become mature. None did this year.

Two years ago we predicted that at least five colleges and universities would choose pro-transgender activism works in 2017. Only two did: Janet [Charles] Mock’s Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More, at University of California, Davis, and Amy Ellis Nutt’s Becoming Nicole: The Transformation of an American Family at Arcadia University in Pennsylvania. This year, however, seven colleges chose transgender-activism works: California State University Northridge, California State University Sacramento, and Illinois Wesleyan University chose Amy Ellis Nutt’s Becoming Nicole: The Transformation of an American Family; Fashion Institute of Technology and Northern Vermont University chose Dashka Slater’s The 57 Bus: A True Story About Two Teenagers and the Crime That Changed Their Lives; Northern Michigan University chose Janet [Charles] Mock’s Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More; and University of Northern Iowa chose Brice D. Smith’s Lou Sullivan: Daring to be a Man Among Men. Our original prediction was premature by one year.

We have made several years of reasonably successful predictions, and we think we have made our point about the common reading genre’s homogeneity and predictability. We will not make new predictions for the coming year.

Honorable Mentions

Colleges

Every college that assigned a work written before 2000 is to be commended for assigning books that will introduce students to the broader expanses of human history. We wish to single out for honorable mention a number of institutions that made especially good common reading selections.

| Institution | Author | Work |

|---|---|---|

| Arizona State University, School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership | Henry Brooks Adams | Democracy: An American Novel (1880) |

| Bucknell University | Anne Carson | Antigonick (2012) |

| Carthage College | W. E. B. DuBois | The Souls of Black Folks (1903) |

| CUNY Baruch College | Russell Shorto | The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony That Shaped America (2004) |

| Florida College | John Hersey | Hiroshima (1946) |

| Harding University | C.S. Lewis | Mere Christianity (1952) |

| Los Angeles Valley College | Ursula K. LeGuin | The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) |

| Luther College | Homer | The Odyssey (ca. 800 BC) |

| Mansfield University of Pennsylvania | Rober Louis Stevenson | The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) |

| Moravian College | John Hersey | Hiroshima (1946) |

| Princeton University | Keith Whittington | Speak Freely: Why Universities Must Defend Free Speech (2018) |

| Rutgers University, Honors College | Stephen Pinker | Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (2018) |

| The King’s College | William Shakespeare | Macbeth (1606) |

| University of California, Santa Cruz, Rachel Carson College | John Steinbeck | The Grapes of Wrath (1939) |

| University of Central Florida | Zora Neale Hurston | Dust Tracks on a Road (1942) |

| University of Mississippi | William Faulkner | Collected Stories (1950) |

| University of Nebraska Omaha | Willa Cather | My Ántonia (1918) |

| University of Pennsylvania | Thornton Wilder | The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927) |

Publishers

Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers, containing works by Cicero, Epictetus, and Seneca.6 Simon & Schuster now likewise offers a Classics series, including Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22.7 Penguin Random House offers two titles that depart from current progressive orthodoxies, Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt’s The Coddling of the American Mind and Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life.8 We encourage common reading selection committees to choose superior offerings such as these, so as to encourage common reading publishers to pursue this turn to classics and unorthodox modern books.

Advice to Improve the Current Common Reading System

Advice for Aspiring Common Reading Authors

The National Association of Scholars has received several queries from would-be common reading authors about how best to market their books to common reading selection committees. We are severe critics of how common reading programs currently work—but we are also fairly well informed about how common reading programs work. We feel sympathy for any author trying to market his work, even when we think his books are inappropriate for college common readings, so we have freely shared our practical advice. This advice has met with some success.

We would rather that colleges assigned classics by dead authors. But as a second-best solution, we would rather colleges assigned books from a wide selection of authors, so as make common readings less homogenous. We, therefore, offer this advice to any would-be common reading author—and to their publishers.

Eleven Tips

- Write for Common Reading Committees’ Preferences. Common reading committees’ favorite subject matters are “timely” progressive political themes, such as racial discrimination, illegal immigration, environmentalism, transgenderism. Their favorite genres are nonfiction, memoirs, and novels. They prefer uplifting books with protagonists under 18 that promote collective activism. They want easy-to-read prose.

- Market Your Book for Common Reading Committees’ Preferences. Many common reading committees put their mission statements and guidelines on the web. Authors should read these guidelines and tailor their publicity material accordingly. North Carolina State University’s Common Reading Selection Committee’s guidelines (https://newstudents.dasa.ncsu.edu/commonreading/nominate/) are particularly useful, because they quantify what they want in a common reading—criteria such as likelihood that students will read this book, relevance to first-year students, and accurate, respectful portrayals of diverse cultures.

- Identify Your Niche. Common reading committees select within subcategories such as the Environmentalist book, the Illegal Immigration book, and the Race and Crime book. Some colleges prefer blander books, such as The Other Wes Moore; some prefer more hard-edged books, such as The New Jim Crow. Situate your book within the common reading genre as a whole. Tailor your arguments: My book resembles a book you have chosen in the past or You have not yet chosen a book like mine.

- Plan a Multi-Year Campaign. If you can get your book selected once, there’s a fair chance it will get chosen in the future. A college common reading committee that isn’t interested the first year your book is published may be interested the second or third year. Work so that interest builds during several years. Include affidavits from colleges where your book was selected as a common reading in your publicity material for later years.

- Get a Booth at the Annual First Year Experience Conference. You (or better yet your publisher) should get a booth at this conference, which briefly possesses the highest concentration nationwide of common reading selectors. You can market to common reading committee members in person, make a positive personal impression, and get a sense of what common reading committees are looking for.

- Prepare a Package Deal. The big common reading publishers provide a package deal—book, speaker tour, and a packet of discussion prompts to help teachers lead student discussions of the book. Write up your own discussion prompts, determine in advance how much you will charge to come speak, and prepare an uplifting speech you can deliver to students.

- Underbid the Premium Talent. Ta-Nehisi Coates charges a lot to come speak at a college. Lots of selection committees don’t have the money to pay for him. Prepare a low-cost bid—especially when you are trying to make a name for yourself. It never hurts to be the cheap alternative.

- Tailor Your Approach. Look at individual colleges and their selection committees and tailor your approach accordingly. Many colleges look for books by alumni, about their region, or connected to their religious affiliation, if they have one. Don’t confine your sales campaign to colleges where you can argue a special connection—but make a harder sell to colleges where you can claim one.

- Be Sincere, Or At Least Fake It. Common reading selection committees are looking for an author who is basically interchangeable with his book—a Good Person Sincerely Preaching a Good Cause. If you think you are one, practice to polish your goodness. If you think you aren’t one, practice to make people think you are good. Keep your private life squeaky clean: If you get caught doing something sleazy, you won’t be on any more common reading shortlists.

- Be Persistent. If you just send one email, it’s likely to be forgotten or ignored. Send follow-up emails after a decent interval, each with new information. If your book was selected at another institution, that’s a perfect occasion for a new email. So is describing how your latest campus visit went. Don’t harass, but keep on selling yourself.

- Write Another Book. Your book will stop being timely. But if selection committees like your book, and like you as a speaker, they’ll be inclined to take a look at the next book your write. Keep up producing a stream of broadly similar books and you can stay on the common reading circuit for the rest of your life.

Advice for Common Reading Selection Committee Members

What can you do if you are a common reading committee member who wants to choose a better book—a classic with literary quality—and your fellow committee members appear dead set on choosing a vapid, forgettable book? We know that common reading selection committees often contain people who would choose better books if they could, but cannot prevail against their fellow committee members, or over supervising bureaucrats. We offer them the following template for securing better common readings.

Eleven Recommendations

- Consult the National Association of Scholars’ list of classic selections. The NAS provides a list of classic common reading selections between 2007 and 2017, with additional supplements each year. (Appendix IV Classic Common Reading Texts) We define “classic selections” loosely as any book published before 1990. To say a book has already been chosen by a common reading committee is itself a strong argument toward saying it can be chosen again.

- Consult the National Association of Scholars’ list of Recommended Books. Our on-line Appendix III: Recommended Books for College Common Reading Programs includes brief rationales for the books we recommend. See whether these can serve as useful models as you develop your own rationales for the books you nominate.

- See how other common reading committees have justified previous classical selections. In the last decade, for example, Le Moyne College selected Bartleby the Scrivener (185, Ithaca College selected Walden (1854), and Lafayette College selected On Liberty (1859). Look on their websites to find out how they justified these choices. Send inquiring emails, both to find out the written justifications and to get in touch with members of their selection committees. An explanation that worked for them may work for you.

- Choose classics that overlap with progressive priorities. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) has been selected 16 times since 2007. It hits a sweet spot—science fiction, it sets up a discussion about science, medicine, and mortality, and feminist bragging rights. African American classics such as Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845), The Souls of Black Folk (1903), and Dust Tracks on a Road (1942) also get selected fairly frequently. Make your own classic suggestions accordingly. If there is a strong push for a transgender subject matter, suggest Virginia Woolf’s short novel Orlando (1928); if a push for environmentalism, suggest John Muir’s My First Summer in the Sierra (1911).

- Choose classics with local resonance. Every region of America has a rich literature, and suggestions for classics should be tailored to fit the region. The University of Central Florida has selected Dust Tracks on a Road and the University of Mississippi has chosen selected stories by William Faulkner. In like manner, a New Mexico college might choose Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927), an Ohio college might choose Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919), and a New Hampshire college might assign Robert Frost’s New Hampshire (1924). If your college is fortunate enough to have a good classic writer among its alumni, plug that writer’s work heavily. If you are at Bowdoin College, look to see what works by Nathaniel Hawthorne might do; if you are at Syracuse University, suggest something by Joyce Carol Oates.

- Develop a list of modern classics. Administrative allergy to any difficult prose may make it impossible to select works not written in something very close to modern American English. Focus on books written after 1918, and especially those written after 1945. From our own list of recommended books, you might therefore push for works such as The Double Helix (1968), Angle of Repose (1971), Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974), or The Right Stuff (1979).

- Select classics recently adapted for film or television. Common reading committees prefer books that have been adapted for film or television, on the grounds that they are more “accessible” or “relatable” for students. Make your suggestions accordingly. For example, forthcoming adaptations of classics into movies include Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868, film adaptation forthcoming in 2019), C. S. Forester’s The Good Shepherd (1955, film adaptation as Greyhound forthcoming in 2020), and George Orwell’s 1984 (1948, film adaptation forthcoming in 2020).

- Canvass potential faculty adopters beforehand. Many common reading programs depend on voluntary faculty adoption of common readings for maximum effect. Canvass faculty, especially those teaching introductory classes, about classic selections they might use in class. It will make a powerful argument if you can come to the common reading selection committee and say, Twenty professors in ten departments have stated that they would be glad to teach this classic book.

- Cultivate student allies. Many common reading selection committees have student members. Usually these are clients of the co-curricular bureaucracy who are equally dead-set on choosing mediocre, progressive modern books. Yet it is worth seeing if you can find a student client of your own—someone interested in classic books, or at least open to them. If you can arrange for support from a student colleague on your committee, or even arrange matters so the student makes the suggestion, this will argue strongly against the idea that a classic book is “elitist,” “out of touch,” or “irrelevant.”

- Use funding as a lever. Many common reading programs are run by administrators dead set on assigning mediocre works of modern progressive propaganda; at others, such administrators have a blocking veto. In such situations, the only way to counter these dead weights is to find out a way to tie bringing money to the college to using a classic selection. Get an outside source to pay for book purchases, speaker fees, and staff time to prepare and run the program. Indifferent college presidents and deans may allow a good common reading if it pays for itself.

There are two possible routes:

A. Seek out grant funding. You can apply to a great many public and private grants supporting common reading programs, either alone or in combination with a local public library system. Donors such as the John Templeton Foundation fund grants in loosely defined areas such as “Character Virtue Development,” for which a good common reading program might qualify. A great many of these programs are skewed toward selecting the same mediocre modern progressive books—but it doesn’t hurt to apply, using the same sort of arguments that you would use toward fellow committee members. And if (for example) you receive $100,000 to support five years of classic common readings, and you stick around to administer the grant program, you should be able to persuade cost-conscious administrators to side with you to overrule administrative ideologues.

B. Cultivate potential donors. This is more haphazard, but still worth exploring. A classic common reading program should be affordable at most colleges for less than $20,000 annually. Most colleges have a body of alumni and other donors who can afford to give that much. There is no standard approach to such donors—especially if you are trying to circumvent the college’s own development office. But it wouldn’t hurt to prepare a thirty-second spiel for the off chance that you’ll get the opportunity to talk to a like-minded donor. It would also help if you have a prepared outline of what you plan to do—your grant application, for example.

- Reinstate a core curriculum. Many of the best common readings are anchored in core curriculum programs. In 2018 Carthage College chose W. E. B. DuBois’ The Souls of Black Folks as its common reading; the book was already part of its required Western Heritage sequence. Luther College’s selections, which include superior choices such as Homer’s The Odyssey and George Orwell’s 1984, are associated with its Paideia program. The best way to secure a classic common reading is to secure a solid core curriculum.

Of course, securing a solid core curriculum where you don’t already have one is a very difficult task—at first glance, a much harder task than getting a better common reading. But faculty can press autonomously and collectively for a core curriculum, and present a solid front against the administration when they do so. It is a difficult task, but one with great benefits. Above all, the core curriculum provides an institutional structure and commitment that can justify repelling administrative initiatives to degrade the curriculum and faculty power piecemeal—not just in the common reading programs, but everywhere.

A common core is the most practical administrative tool for the faculty to preserve its authority against a power-hungry administration.

While the best common core would be tightly focused on Western civilization, any common core that is not centered around social justice, or other euphemisms that subordinate the search for truth to faith in progressive politics, would be preferable to the distribution-requirements-and-elective system. Certainly, common readings in the absence of a common core will inevitably drift toward administrative priorities rather than academic ones. The best long-term solution to ensure better common readings is a core curriculum.

These are first suggestions—and we would gladly welcome further practical suggestions from members of common reading selection committees. The two general principles behind these suggestions are: 1) spend serious and continued time working to select classic common readings; and 2) play hardball academic politics to get classic common readings selected.

New Recommended Books

Each year the National Association of Scholars recommends new books for common reading programs. We recommend both books appropriate in level of difficulty and length for any college freshman and choices that are more ambitious in length and complexity. Our list is intended to stimulate scholars who wish their institutions to select better common readings, not to provide an exhaustive list of proper common readings.

Our full list may be found on-line, in our Appendix III: Recommended Books for College Common Reading Programs. Here we provide 15 New Recommended Books Appropriate for Any College Common Reading Program, 5 New Recommended Books Appropriate for More Ambitious College Common Reading Programs, and our full list of 150 Recommended Books.

15 New Recommended Books Appropriate for Any College Common Reading Program

HENRY BROOK ADAMS – DEMOCRACY (1880)

Adams’s classic political novel highlights the pettiness and venality of America’s elected representatives—and with a light touch explores what can be achieved by a democratic government that must work through the fallible men who wield the levers of power. Recommended for colleges that seek a sober but enjoyable appraisal of the strengths and weakness of the American government, which is no better—and no worse—than the American people.

JIM BOUTON – BALL FOUR (1970)

Fading pitcher Jim Bouton kept a diary during his 1969 season. Engaging malcontent Bouton bounced between the minor and the major leagues, pleaded with his coaches to let him pitch a knuckleball, recorded the unvarnished language, drinking, and affairs of his team-mates and managers, and glanced at the 1960s social revolutions from the vantage point of the pitcher’s mound. This classic account of a professional athlete’s life is recommended for common reading committees interested in sports memoirs.

MIKHAIL BULGAKOV – THE HEART OF A DOG (1925)

Dr. Preobrazhensky uses surgery to transform the dog Sharik into a human being—but he still has the heart of a dog. Sharik is violent, uncouth, an eager servant of the new Soviet state, and eventually becomes an informer for the secret police. Bulgakov’s savage anti-Bolshevik satire also ridicules the hopes of any political reform or scientific advance to change man’s essential nature. Recommended for colleges exploring the connections between science and politics.

ANTHONY BURGESS – A CLOCKWORK ORANGE (1962)

Alex is your ordinary teenage delinquent. He likes dressing up, classical music, and whatever offers in the way of assault, rape, and murder. He is arrested, imprisoned, and then brainwashed to be good—not because he wants to, but because he has to. Can you make evil people be good? It is a worse evil to force them to be good? Recommended for colleges interested in science fiction. Note: Reading discussion should focus on the differences between the grim 20-chapter version of the book and the more hopeful 21-chapter version.

EURIPIDES – MEDEA (431 BC)

Jason decides to divorce Medea—to secure an advantageous second marriage for himself and (he tells Medea) to use his new connections to give his children with Medea a better life. Medea decides that her self-respect requires her to kill not only Jason’s new wife but also her own children. Is Medea a feminist heroine or a monster? No playwright has ever explored more acutely what it means for a woman to claim the dignity of a man. Recommended for colleges discussing the status of women.

EDWARD FITZGERALD – RUBÁIYÁT OF OMAR KHAYYÁM (1859)

Medieval Persian poet Omar Khayyam wrote romantic and philosophical verse. Edward Fitzgerald’s extremely loose translation turned Khayyam into a gloriously Victorian English mystic and skeptic. Fitzgerald’s poetry beautifully evokes love and faith; they also demonstrate how much the world has gained from Westerners’ affectionate, creative misreadings of non-Western texts.

HERMAN HESSE – DEMIAN (1919)

Emil Sinclair comes of age; psychologically tortured by bullies, tempted toward corruption, he eventually learns a better path from his schoolmate Max Demian. Demian instead points to a life dedicated toward self-exploration, whatever self you happen to possess. Colleges interested in character education can benefit by having students discuss the positive and negative features of Demian’s woozy German mysticism, which oscillates between inculcating a healthy rejection of salvation via collective endeavor and inculcating an appalling narcissism.

YASUNARI KAWABATA – SNOW COUNTRY (1948)

Shimamura is rich, from Tokyo, an expert in Western ballet. Komako is a geisha in provincial Yuzawa; she practices the samisen by listening to the radio and reading sheet music. Their love affair cannot last. Kawabata’s novel incorporates the dichotomy of traditional Japan and the modern West into a classic Japanese story that likewise fuses traditional Japanese prose and imagery with Western Expressionism. Recommended for colleges interested in robust traditionalism that self-confidently appropriates Western culture.

ARTHUR KOESTLER – THE CASE OF THE MIDWIFE TOAD (1971)

Biologist Paul Kammerer advocated Lamarckism—the idea that organisms pass on acquired characteristics to their children, and not just inherited ones. He was accused of fraud and committed suicide. Koestler tells his story with verve and pathos, and suggests that maybe Kammerer was framed, not fraudulent. And devotees of “epigenetics” are reviving quasi-Lamarckian thought; could there be anything to Kammerer’s ideas? Recommended for colleges focused on scientific debate.

MARCUS AURELIUS – MEDITATIONS (CA. 180)

Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius articulated Stoic philosophy in these terse, compelling meditations. Aurelius teaches the reader how to ignore the distractions of pain and pleasure, to seek out dispassion and a sense of proportion, and to use your rational mind to seek to do good. Students will especially benefit from reading Aurelius in an age that glorifies unreflective passion, the embrace of victimhood, and irreconcilable resentment. Recommended for colleges interested in character education.

VILHELM MOBERG – THE EMIGRANTS (1949)

Karl and Kristina Nilsson emigrate from impoverished rural Sweden to the United States; after a grueling sea voyage, they arrive in their strange new home in 1850. Moberg’s novel is a fine character study of different sorts of Swedish emigrants, documentarily precise, and brings to life the great mid-nineteenth century wave of immigration that transformed America. Recommended for colleges discussing immigration to America.

NATSUME SOSEKI – BOTCHAN (1906)

Botchan is a Tokyo roughneck too quick with his fists, but he means well. Naturally, he ends up teaching math to middle-schoolers. He quarrels with the students, quarrels with his fellow teachers, but ends up giving a good drubbing to the smooth-tongued head teacher, who really deserves it. This classic comic novel demonstrates that mistrust of arrogant, would-be intellectuals is universal. Recommended for colleges with large numbers of education majors.

MURIEL SPARK – THE PRIME OF MISS JEAN BRODIE (1961)

Miss Jean Brodie gives her students in a 1930s Edinburgh girls school a lovingly individual education in art history, romance, classical studies—and political engagement for the Fascist cause. One student dies; another betrays her. Students will learn that they should not always trust their excitingly dedicated teachers. Recommended discussions on the virtues and drawbacks of loyalty.

RABINDRANATH TAGORE – THE HOME AND THE WORLD (1916)

Nikhil and Bimala are a gentle loving couple who are tempted to leave their traditional mores by the alluring Indian nationalist Sandip—and learn that Sandip is an unscrupulous man who uses nationalism to serve himself. Tagore, the great figure of modern Bengali literature, wrote a subtle analysis of the attraction and power of nationalism, and how it too can be corrupted. Recommended for colleges fostering discussion about the promises and dangers of political engagement.

LIONEL TRILLING – THE MIDDLE OF THE JOURNEY (1947)

John Laskell recovers from a grave illness and spends the summer with his friends: the near-Communists Arthur and Nancy Croom and the brooding ex-Communist Maxim Gifford. The Crooms’ vicious sentimentality—their willingness to excuse any personal misbehavior by a member of the “working class”—jolts Laskell out of his acquiescence to soft-Communist ideals. He ends the novel committed to defend liberalism against both Communism and conservatism. Trilling’s fine political novel is recommended for colleges sparking student debates about political philosophy.

5 New Recommended Books Appropriate for More Ambitious College Common Reading Programs

ANTON CHEKHOV – THE CHERRY ORCHARD (1904)

The noblewoman Lyubov Andreievna Ranevskaya returns to her family estate one last time, before it is sold off to pay for the mortgage. The merchant Lopakhin, son of an ex-serf, buys the estate; his triumph, the cutting down of Lyubov’s beloved cherry orchard for the value of the timber, is her tragedy. Students will learn from Chekhov that comedy is inseparable from tragedy, and victory from defeat. Recommended for colleges teaching empathy to their students.

J. HECTOR ST. JOHN DE CRÈVECŒUR – LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN FARMER (1782)

Crèvecœur’s fictional letters explore the geography, economy, and society of the newborn America, including the nature of slavery and the frontier struggles with the Native Americans. This early study of the nature of America is as sprawling as the America it describes. Recommended for colleges prompting students to consider how much of America is the same as when it was born, and how much has changed.

WALTER KEMPOWSKI – ALL FOR NOTHING (2006)

It is January 1945 in East Prussia, and the Russians are about to invade. Kempowski delineates every aspect of a world on the eve of annihilation—Nazis and aristocrats, artists and schoolteachers, Polish slave laborers and Jews on the run. The reader knows it will be destroyed as the payment for following the Nazi will-o-the-wisp of conquest, loot, and slaughter—all gone for nothing. Kempowski lets us know how just is the Russian retribution to come, and how terrible that justice. Recommended for colleges prompting students to consider the consequences of being sure that history is on your side.

KARL POPPER – THE LOGIC OF SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY (1934)

Popper argue that the proper scientific methodology should be based on the principle of falsifiability: No experiment can prove a theory, but properly reproducible observations and experiments can falsify one. Popper’s book is a modern classic of scientific epistemology. This book is especially recommended for colleges focusing on science and technology, but all students will benefit from discussing whether an unfalsifiable theory has any intellectual value.

JUNICHIRO TANIZAKI, THE MAKIOKA SISTERS (1948)

The Makioka family’s fortunes are declining in the late 1930s: The unmarried sisters must judge different marriage proposals, or whether to reject marriage entirely, while the shadows of the war with China are lengthening over pre-war Japan. The Makioka Sisters is an epic account of Westernization and women’s roles, but above all it is the great realistic novel about interwar Japan. Recommended for colleges introducing their students to the best literature of the non-Western world.

150 Recommended Books

110 Recommended Books Appropriate for Any College Common Reading Program

Edwin Abbott Abbott – Flatland (1884)

Chinua Achebe – Things Fall Apart (1958)

Henry Books Adams – Democracy (1880)

James Agee – A Death in the Family (1957)

Kingsley Amis – Lucky Jim (1954)

Roy Chapman Andrews – Under A Lucky Star (1943)

Jean Anouilh – Antigone (1944)

S. Ansky – The Dybbuk (1920)

Aristophanes – The Clouds (423 B.C.)

Louis Auchincloss – The Rector of Justin (1964)

Augustine – Confessions (398 A.D.)

Jane Austen – Persuasion (1817)

Mariano Azuela – The Underdogs: A Novel of the Mexican Revolution (1915)

The Book of Ecclesiastes (C. 970-930 B.C.)

The Book of Job (C. 1000 B.C.)

F. Bordewijk – Character: A Novel of Father and Son (1938)

Jim Bouton – Ball Four (1970)

Elizabeth Barrett Browning – Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850)

Mikhail Bulgakov – The Heart of a Dog (1925)

John Bunyan – The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678)

Anthony Burgess – A Clockwork Orange (1962)

Pedro Calderon de la Barca – Life is a Dream (1635)

Albert Camus – The Plague (1947)

Willa Cather – Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927)

John Chadwick – The Decipherment of Linear B (1958)

Joseph Conrad – Under Western Eyes (1911)

James Fenimore Cooper – The Last of the Mohicans (1826)

Charles Darwin – The Voyage of the Beagle (1839)

Charles Dickens – American Notes for General Circulation (1842)

Annie Dillard – Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974)

John Donne – Divine Poems (1633)

Fyodor Dostoevsky – The House of the Dead (1862)

Ralph Ellison – Invisible Man (1952)

Shusaku Endo – Silence (1966)

Desiderius Erasmus – The Praise of Folly (1509)

Euripides – Medea (431 BC)

Everyman (C. 1500)

David Hackett Fischer – Washington’s Crossing (2004)

M. F. K. Fisher – How to Cook a Wolf (1942)

Edward Fitzgerald – Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (1859)

Gustave Flaubert – A Simple Heart (1877)

Benjamin Franklin – Autobiography (1791)

Robert Frost – New Hampshire: A Poem with Notes and Grace Notes (1923)

Nathaniel Hawthorne – The Blithedale Romance (1852)

William Least Heat-Moon – Blue Highways (1982)

Herman Hesse – Demian (1919)

Andrew Hudgins – After the Lost War (1988)

Zora Neale Hurston – Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

Henrik Ibsen – An Enemy of the People (1882)

Jane Jacobs – The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961)

Henry James – What Maisie Knew (1897)

Jerome K. Jerome – Three Men in a Boat (1889)

Ryszard Kapuscinski – The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat (1978)

Yasunari Kawabata – Snow Country (1948)

William Kennedy – Ironweed (1983)

Richard Kim – The Martyred (1964)

Rudyard Kipling – Kim (1901)

Arthur Koestler – Darkness at Noon (1940)

Arthur Koestler – The Case of the Midwife Toad (1971)

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing – Nathan the Wise (1783)

Carlo Levi – Christ Stopped at Eboli (1945)

Primo Levi – The Periodic Table (1975)

Sinclair Lewis – Babbitt (1922)

A. J. Liebling – The Earl of Louisiana (1961)

Abraham Lincoln – Selected Speeches and Writings (1832-1865, pub. 2009, selections)

Federico Garcia Lorca – The House of Bernarda Alba (1936)

Marcus Aurelius – Meditations (C. 180)

John Stuart Mill – On Liberty (1869)

Vilhelm Moberg – The Emigrants (1949)

Molière – Tartuffe (1664)

Michel de Montaigne – An Apology for Raymond Sebond (1580-1595)

Thomas More – Utopia (1516)

John Muir – My First Summer in the Sierra (1911)

Reinhold Niebuhr – The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness (1944)

Sean O’Casey – The Shadow of a Gunman (1923)

George Orwell – Homage to Catalonia (1938)

Francis Parkman – The Oregon Trail (1847)

Plato – Apology of Socrates and Crito (C. 399-387 B.C.)

Plutarch – Parallel Lives (C. 100) (Selections)

Alexander Pope – Essay on Criticism (1711)

Dorothy Sayers – Gaudy Night (1935)

Seneca – Letters from a Stoic (C. 65) [Penguin Classics Edition, Selected Letters]

William Shakespeare – Henry V (C. 1598)

William Shakespeare – Richard III (C. 1592)

George Bernard Shaw – Major Barbara (1905)

Isaac Bashevis Singer – Satan in Goray (1933)

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (C. 1350-1400)

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962)

Natsume Soseki – Botchan (1906)

Thomas Sowell – A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles (1987)

Muriel Spark – The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961)

Wallace Stegner – Angle of Repose (1971)

Robert Louis Stevenson – A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa (1892)

J. M. Synge – The Playboy of the Western World (1907)

Rabindranath Tagore – The Home and the World (1916)

Leo Tolstoy – Hadji Murad (1912)

Lionel Trilling – The Middle of the Journey (1947)

Anthony Trollope – The Warden (1855)

Ivan Turgenev – Fathers and Sons (1862)

Mark Twain – Life on the Mississippi (1883)

Miguel de Unamuno – Saint Manuel the Good, Martyr (1931)

Voltaire – Candide (1759)

Robert Penn Warren – All the King’s Men (1946)

James D. Watson – The Double Helix (1968)

H. G. Wells – The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896)

Walt Whitman – Leaves of Grass (1855-92)

Oscar Wilde – The Importance of Being Earnest (1895)

Thornton Wilder – Heaven’s My Destination (1934)

Tom Wolfe – The Right Stuff (1979)

40 Recommended Books for More Ambitious College Common Reading Programs

Matthew Arnold – Culture and Anarchy (1869)

William Bartram – Travels of William Bartram (1791)

Jacques Barzun – Berlioz and His Century (1950)

Brendan Behan – Borstal Boy (1958)

Ruth Benedict – Patterns of Culture (1934)

Benvenuto Cellini – The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini (1558-1563)

Miguel de Cervantes – Don Quixote (1605)

Whittaker Chambers – Witness (1952)

Anton Chekhov – The Cherry Orchard (1904)

Pierre Corneille – The Cid (1637)

James Gould Cozzens – Guard of Honor (1948)

J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur – Letters From An American Farmer (1782)

Daniel Defoe – Roxana (1724)

Fyodor Dostoevsky – Crime and Punishment (1866)

George Eliot – Middlemarch (1871-1872)

Mouloud Feraoun – Journal, 1955-1962 (1962)

Patrick Leigh Fermor – A Time of Gifts (1977)

Ronald Fraser – Blood of Spain (1979)

Hamlin Garland – Main-Travelled Roads (1891)

George Gissing – The Odd Women (1893)

Jaroslav Hasek – The Good Soldier Svejk (1923)

William Dean Howells – The Rise of Silas Lapham (1885)

Johan Huizinga – The Waning of the Middle Ages (1919)

Walter Kempowski – All For Nothing (2006)

Herman Melville – Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866), excerpts

Herman Melville – The Confidence-Man (1857)

Vladimir Nabokov – Speak, Memory (1966)

V. S. Naipaul – The Loss of El Dorado (1969)

John Henry Newman, The Idea of a University (1852)

Eugene O’Neill – Long Day’s Journey into Night (1941-1942)

Karl Popper – The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1934)

Gary Rose, Ed. – Shaping a Nation: 25 Supreme Court Cases (2010)

Robert Skidelsky – John Maynard Keynes 1883-1946: Economist, Philosopher, Statesman (2005)

Eugene B. Sledge – With the Old Breed (1981)

Stendahl, The Red and the Black (1830)

Junichiro Tanizaki – The Makioka Sisters (1948)

Alexis de Tocqueville – Democracy in America (1838)

Virgil – The Aeneid (19 B.C., Fagles’ trans., 2006)

Edith Wharton – The House of Mirth (1905)

Edmund Wilson – To the Finland Station (1940)

Recommendations

General Selection Principles

- Seek books that encapsulate intellectual diversity, not books that preach one message.

- Seek books that stretch students’ minds: neither too short nor too long; neither too simple nor too complex; but sufficient to challenge and delight a young adult’s inquiring mind.

- Seek books that see man in his moral complexity and balance between Pollyanna optimism and cynical contempt.

- Seek works of fiction that combine beauty of language, intellectual complexity, and moral seriousness.

- Seek works of nonfiction that combine elegance, lucid argument, and respectful awareness that their readers should not be preached at, but persuaded.

- Seek challenging books in preference to inoffensive ones.

- Seek out important books from earlier eras.

- Consult peers who read widely and who are intimately acquainted with good books.

- Consult outside sources, such as the National Association of Scholars’ list of Recommended Books (see Appendix III: Recommended Books for College Common Reading) or Modern Library’s list of 100 Best Novels and 100 Best Nonfiction.9

- Avoid books chosen for their subject matter, or books chosen to be inspirational; books chosen on those grounds are usually dull, often poorly written, and seldom distinguished.

- Avoid books that appear in publishers’ First-Year Experience catalogs.

- Seek out books that will lift up the institution’s academic standards and contribute to its intellectual reputation.

Mission Statements

Common reading programs’ mission statements should be altered to include some or all of the following elements:

- Academic Outcomes: Common reading programs should dedicate themselves to preparing students for college-level academic work.

- Academic Assessments: Common reading programs should assess their success by how well they prepare students for college-level academic work.

- Selection Criterion: Full-Length Books: Common reading programs should select at least one full-length book, with a minimum of 50,000 words of college-level prose (the length of The Great Gatsby) or 5,000 words of prosodically sophisticated poetry.

- Selection Criterion: Older Works: Common reading programs should require, or give strong preference to: 1) books written before 1923, and hence in the public domain; 2) books written by dead authors; and/or 3) books published at least 20 years in the past.

- Common reading committees could make it part of their mission statement to choose a classic at least once every four years.

- Common reading committees could make it a rule that every common reading shortlist must include at least one classic.

- Selection Criterion: Intellectual Complexity: Common reading programs should commit to selecting intellectually complex books, appropriate for college-level discussion.

- Selection Criterion: Literary Quality: Common reading programs should require books that exemplify beautiful writing, and are not merely efficient conveyors of information.

- Selection Criterion: Fiction: Common reading programs should give strong preference to works of fiction. Common readings should seek to develop literary readers, whose imaginative empathy contributes to the habits of good citizenship.

- Selection Criterion: Translations: Common reading programs should seek out works in translation. Colleges and universities should aim to introduce students to the broader world, and not be parochially reliant on English-speaking American authors.

- Selection Criterion: Mature Protagonists: Common reading programs should seek out works of fiction with mature protagonists, which will introduce college students to the way that adults through the centuries have thought, felt, and behaved.

- Selection Criterion: Local Subject Matter: Common reading programs should seek out works by alumni and works about the institution’s locality or state.

- Selection Criterion: Common American Character: Common reading programs should seek out books that emphasize what Americans share in common rather than to books that emphasize what divides them.

- Selection Criterion: Good Academic Character: Common reading programs should seek out books that encourage intellectual humility, freedom of speech, individual dissent, and self-control.

- Selection Criterion: Encourage Debate: Common reading programs should seek out books that challenge students precisely because they do not endorse “institutional values”—which all too often nowadays are statements of progressive dogma.

If they are all adopted, the Selection Criteria of Translations, Mature Protagonists, Local Subject Matter, and Common American Character should be harmonized as much as possible. Where they conflict, the order of priority should be Common American Character, Local Subject Matter, Mature Protagonists, and Translations. Selection committees might consider dedicating one slot apiece on common reading shortlists for books in each of these four categories.

Faculty Management

We recommend administrative reforms to shift the management of common reading programs from the “co-curricular” bureaucracy to the faculty.

- Committees of Professors: Common reading committees should be staffed exclusively by professors and librarians.

- Management by Regular Disciplinary Departments: A majority of common reading committee members should be professors in regular disciplinary departments that specialize in teaching students how to read books (e.g., English, History, Philosophy).

- Tenured Professors as Committee Chairs: Common reading committees should select tenured professors as their chairs.

- Small Committees: Common reading selection committees should consist of no more than 5 members.

- Small Shortlists: Common reading committees should have shortlists of no more than 5 books, so as to allow committee members the time to read each book carefully.

- Consultation with Composition Departments: Composition (writing) professors and instructors ought to be consulted during book selection.

- Appointment of Student Discussion Leaders: Committee members should choose discussion leaders from senior Literature majors, Literature graduate students, or equivalently trained students, properly compensated for their time.

- Selection of Academic Speakers: Common reading committees should select professors, or other figures whose interests are primarily intellectual, to speak at lectures, symposia, and other events linked to the common reading.

- Composition of Associated Materials: Common reading committees should compose their own discussion guides, essay prompts, and other associated materials.

- Voluntary Professorial Adoption: Common reading committees should select books that professors throughout the institution will voluntarily integrate into their syllabi.

- Professorial Recompense: All committee members should have their teaching load (or equivalent library duties) reduced by at least 1 course a year.

Program Structure

Common reading programs also should be reformed by a series of measures not directly related to establishing faculty management.

- External Oversight: External oversight committees should inspect common reading programs at public universities and recommend ways to render them politically impartial.

- Adopt Best Existing Practices: Some common reading programs already select classics and recently published intellectually challenging books. Their peers should adopt administrative processes that bring them up to the best existing practices of their peers.

- Disciplinary Alternation: Common reading programs charged with selecting multidisciplinary books should set up a regular disciplinary alternation, in which successive common readings focus on different disciplines.

- Voluntary Readings: Common reading programs should adopt more advanced books as voluntary common readings.

- Discussion Goals: Common reading discussions should aim to elicit thoughtful critique of the text and lively disagreement among students.

- Writing Requirements: Common readings should be integrated with academic writing assignments, as part of a regular class.

- Divorce from Activism: Common readings should not promote pledges, service-learning, civic engagement, or activism of any kind.

- Divorce from Sponsoring Administrative Sub-units: Common reading programs should cut all ties to administrative subunits such as Offices of Diversity or Civic Engagement.

- Reduce or Cap Speaker Fees: Funds previously dedicated to speaker fees should be transferred toward subsidizing common reading book purchases for students.

- Fiscal Transparency: Common reading programs should be fiscally transparent, and publicize all costs on their websites.

Donors

Common reading programs often depend on special subsidies from outside donors. We direct the following recommendations to donors considering supporting common reading programs.

- Condition Support: Donors should only fund common reading programs that adopt the mission statements and administrative structures recommended above.

- Require Documentation: Donors should require common reading programs to inform them about teaching guides, lecture selections, and all other ancillary materials.

- Time-Limit Funding: Donors should provide temporary funding for common reading programs, and never endow them.

- Thematic Support: Donors should fund common readings linked to themes such as Classical Learning, Intellectual Diversity, or Institutions of American Liberty.

Institutions of Higher Education

Colleges and universities as a whole must also change their policies so as to make common readings useful components of the education they offer. We make only one recommendation:

- Tighten college admission standards so as to select a student body with the capacity and desire to read a challenging book.

1 David Randall, Beach Books: 2017-2018: What Do Colleges and Universities Want Students to Read Outside Class? (New York, National Association of Scholars, 2018).

2 Ibid.

3 Stanley Kurtz, “Obama’s Secret Weapon: Henrietta Lacks,” National Review Online, August 19, 2013.

4 U.S. News & World Report: National Universities Rankings; National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings.

5 The figures for 2014/2015, 2015/2016, and 2016/2017 are drawn from data that needs to be updated; the data in these columns in probably roughly accurate, but not precisely so.......

6 First Year Common Reading 2019, Princeton University Press, p. 17.

7 Freshman Year Reading Catalog 2018-2019, Simon & Schuster, pp. 12-13.

8 2019 First-Year & Common Reading, Penguin Random House, pp. 28, 36.