Executive Summary

Since 2005, the Chinese government has vigorously extended influence over American education. While well-researched in some areas, that influence is merely noted elsewhere. Much of this research is responsible for successfully shifting the public’s perception of Confucius Institutes. Once thought of as a benign academic exchange and language program, it is now known to be an influence operation lead by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Most Confucius Institutes (CIs) closed as a response to public and legislative scrutiny of the program. However, CI subsidiaries in the form of Confucius Classrooms remained less explored. Last year, the advocacy group Parents Defending Education (PDE) discovered the presence of Confucius Classrooms around 20 US military bases.1 Our report takes these findings into account, and independently documented 164 Confucius Classroom (CC) programs of various size across the US. We discovered CCs in the public schools of major metropolitan areas, in rural school districts, elite private schools, and across entire states.

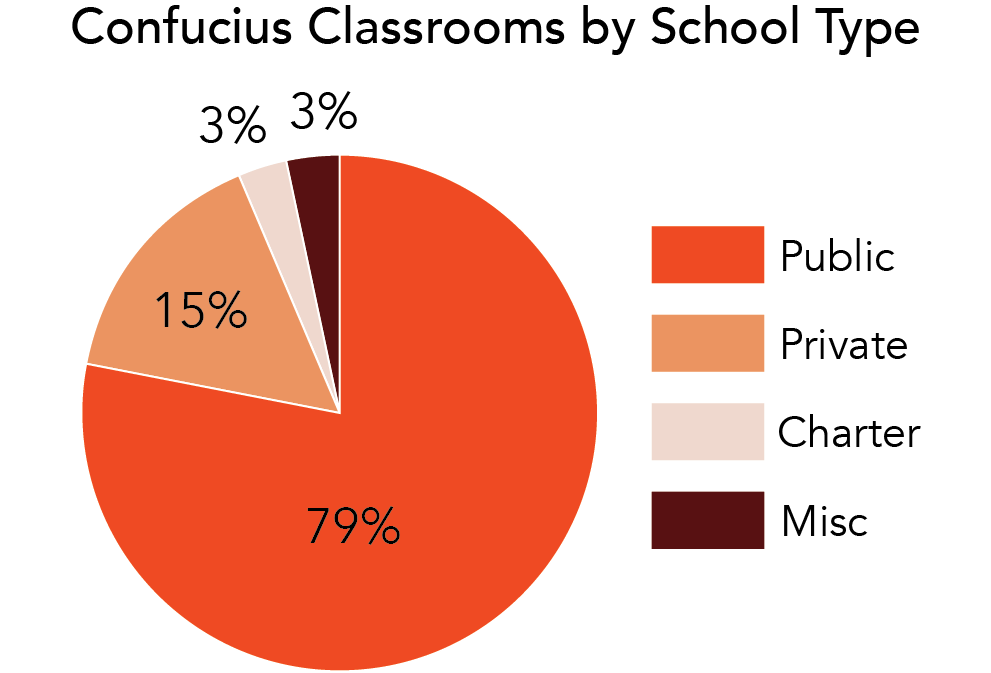

When host schools were categorized by public or private education, 79 percent of these Confucius Classrooms were discovered in public school districts. The exact number of CCs currently in operation is unknown. This is due to the closure and rebranding of Confucius Institutes, a tarnishing of the “Confucius” label for China’s international language program, and the use of nonprofit intermediaries to hide China’s support for Confucius Classrooms.

Research on CCs has largely neglected to contextualize these programs within China’s overall strategy to influence education and other parts of American society. This report demonstrates how CCs fit within China’s efforts to build strategic economic and diplomatic partnerships with local and state officials. In some cases, such as North Carolina and Minnesota, governors forged ties with China at the state level. Major cities, such as Chicago, Seattle, and Portland, established similar relationships with China through bilateral programs.

This report fills a gap in previous work by examining the role of Mandarin education in Communist China, how the CCP developed language as a tool of political warfare, and then deployed it to the United States. Confucius Classrooms did not simply expand CIs into K-12 schools; instead, they grew out of China’s strategy to influence policymakers and society at the state and local levels.

This report finds that Confucius Classrooms:

- Often formed out of bilateral initiatives at local and state levels within the United States. These bilateral initiatives developed into agreements, partnerships, and memos of understanding between state departments of education, governors, and local mayors.

- Emerged in parallel to US-China business ties at the local level. This report finds that CCs sometimes are in close proximity to significant Chinese investments.

- Sometimes operated as Confucius Institutes.

- Use nonprofit intermediaries to avoid public scrutiny. The role of nonprofit intermediaries has been acknowledged before. However, this report finds that nonprofit organizations act as facilitators and sustainers of some Confucius programs.

- Involved bilateral relationships between American schools and Chinese counterparts. Schools with CCs often have “sister school” partnerships with schools in China.

- Represent a point of interest among high-profile Chinese officials involved with China’s United Front Work Department (UFWD).

Confucius Institutes provided one of the support mechanisms for Confucius Classrooms by helping them obtain teachers, funds, and learning materials such as books. Nonprofit organizations similarly helped these programs grow. Nonprofits such as the 100,000 Strong Foundation, Go Global NC, BG Education Management Solutions, IL Texas Global, the Alliance for Education, and the Asia Society played roles in opening American K-12 schools to the Chinese Communist Party. Many of the founders and board members of these nonprofits are high-profile figures from American politics and business.

Methodologically, this report attempts to avoid reexamining previous research on China’s Confucius programs. The 164 cases of Confucius Classrooms in this report include those documented by Parents Defending Education; however, this list includes additional cases found via open-source data from the US and China.

In order to counter the durability and persistence of China’s Confucius programs in education, we recommend three key policies:

- Revitalize the Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA) in order to eliminate exemptions in education, business, and scientific pursuits. As this report illustrates, American nonprofit intermediaries are an important tool for China to shape Chinese language education in American schools. State and local policymakers have similarly engaged in high-diplomacy independent of America’s Congress and the Executive. Closing the loopholes in the Foreign Agent Registration Act is a critical step to rectifying these dynamics.

- Develop Foreign Language Curricula Based on the American Narrative. American students must learn critical languages to compete in the modern economy. Most foreign language programs exclusively focus on incorporating the culture of the target language into the curriculum. It is as critical that American students of Chinese and other critical languages are able to communicate American values and ideas unique to the American experience in a sophisticated manner. Developing a Mandarin curriculum that empowers students to communicate the fundamental ideas of individual liberty, natural rights, and republican governance is necessary for training future leaders.

- Establish Ratio Funding Restrictions on Universities to curtail universities from taking foreign funding that competes with the interest of American taxpayers. This can be achieved through ratio funding restrictions. This is achieved by implementing a tax or fine at a dollar-to-dollar basis on all foreign funds a university receives. Such restrictions would change the incentives for universities to engage in contractual relationships with foreign adversaries such as China.

The first chapter of this report discusses the origins and strategy of China’s use of Confucius as a label for its soft power efforts to gain influence abroad. The role of language education in China’s conduct of political warfare is discussed in the context of how the Chinese Communist Party reformed Mandarin to indoctrinate its population after 1949. This chapter also examines the relationship between Confucius Institutes and Confucius Classrooms, and how Beijing’s Confucius programs differ from the foreign language initiatives of other countries.

The second chapter examines CCs in the US, and how they have been founded and sustained by the efforts of nonprofits and policymakers at the state and local level. This chapter also discusses a number of the nonprofits involved in enabling Confucius Classrooms to survive the closure of Confucius Institutes, and how China’s use of nonprofits demonstrates Beijing’s strategy to use education as a means of influencing other parts of American society. This chapter also notes how CC programs play a role in building economic ties between the US and Chinese business interests.

The third chapter surveys three surviving Confucius Classrooms discovered by Parents Defending Education last year. This chapter examines Minnetonka Public Schools, Sisters School District, and St. Cloud Area Schools, and shows how these schools demonstrate the macro trends discovered in this report. In both Minnesota and Oregon, economic interests and local policymakers played a role in establishing the CCs located there. The fourth and final chapter offers policy recommendations based on the findings of this report.

Chapter 1: The Chinese Communist Party and Language as Soft Power

Introduction

In 1948, one year before the Communist takeover of mainland China and with the realities of the Holocaust and World War Two still vivid memories, the American philosopher Richard Weaver published a book entitled Ideas Have Consequences.2 Weaver argued that rather than consist of rhetorical abstraction, language and the ideas it presents have real-world consequences. Language forms worldviews, and worldviews affects action.

Fully understanding this power of language, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has made its promotion of Mandarin a pillar of its soft power strategy to shape the world in its image.

In 2017, the National Association of Scholars (NAS) sounded the alarm over China’s Confucius Institutes (CIs), pointing out how they threaten higher education by undermining intellectual freedom, jeopardizing university independence, and by projecting CCP propaganda into the classroom.3 CIs, the turnkey Mandarin language programs established and run through the Chinese government, raised concerns across the political spectrum. In response, many universities rebranded, restructured, or closed their CI programs.4 While China’s effort to co-opt American universities is now part of public discourse, a deeper level of CCP influence operates in China’s Confucius Classroom (CC) program at the K-12 level.

Originally run through the Office of Chinese Language Council International, a bureaucracy also known as the Hanban housed within Beijing’s Ministry of Education, the Chinese government opened CIs and CCs around the globe. Amid growing apprehension over growing Chinese influence in US education, the Hanban was later rebranded and restructured into two new organizations called the Ministry of Education Center for Language Exchange and Cooperation (CLEC), and the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF).5

At their peak in 2017, China supported CCs at 501 American schools.6 CCs in the US accounted for 47 percent of all CCP-backed Mandarin K-12 programs worldwide.7 Often, CCs act as subsidiaries of their CI counterparts in higher education. At other times, CCs have been established either through bilateral partnerships between an American school system and Chinese partner schools, or run through nonprofit organizations within the US.

While many CIs formally ceased to exist over the past several years, bilateral ties between universities persisted. A number of constituent CCs similarly survived. Despite the concerns of Federal policymakers, the total number, scope, identity, and location of CCs remained unknown.

A 2023 report conducted by Parents Defending Education (PDE) on Confucius Classrooms notes that the US currently hosts at least 143 active or defunct CCs across 34 states.8 PDE’s findings offer a snapshot of a widespread funding effort by China to monopolize Mandarin education across a range of K-12 schools. In its investigation, PDE discovered $17,967,565.12 flowed into CCs between 2009 and 2023.9 More alarmingly, PDE discovered that CCs cluster around 20 US military bases, and that some CCs have ties to educational institutions in China that are associated with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).10 Our investigation discovered at least 164 schools or school systems where CCs were present either now or in the recent past. In the context of Chinese land purchases around military bases,11 China’s prominence as a source of deadly fentanyl,12 spy balloon flights, and the proximity of CIs to US hypersonic missile technology programs, these findings raise questions about how CCs fit within China’s broader subversion strategy.13

The establishment and spread of Confucius Classrooms reveal three key aspects of their role in China’s broader subversion strategy. First, CCs are an extension of the CCP’s domestic doctrine of advancing political warfare by means of education. Second, China effectively exploits American nonprofits to act as intermediaries in their support for CCs. This reliance on nonprofits has masked the scope of China’s influence and allowed CCs to restructure and survive despite removal of Confucius Institutes from universities. Third, CCs form part of a broader Chinese effort to form business and diplomatic ties with state and local policymakers in the United States.

Previous research on CIs and CCs did not examine the role of local business actors and political officials in enabling the growth, transfer, and survival of CCs in the K-12 system. National initiatives such as the 100,000 Strong Initiative, and local diplomacy between China and American governors, school districts, and municipalities went unexplored. The following sections of this report fill these gaps in the understanding of how CCs fit within the CCPs efforts to subvert US institutions, sovereignty, and shape American perceptions of the Chinese government.

Language Education and Propaganda in Communist China

Political warfare is still warfare, and education is one of its battle domains. The ancient Chinese military theorist Sun Tzu (400-320 BC) declared that “subjugating the enemy’s army without fighting is the true pinnacle of excellence.” [14] As a Communist regime, China has employed education as a pillar of ideological warfare and as a tool for legitimacy since the CCP took power in 1949. Mao Tse-Tung once described “dictatorship” and “democracy” as two pathways to shape the population. In Mao’s thinking, dictatorship was reserved for reactionaries in the form of forced labor and prohibition against political activity. In contrast, Mao reserved “democratic methods” for the education of the general population.15 Under this logic, propaganda and persuasion is deployed for political power prior to resorting to force.16

Unlike the classical Western liberal arts education, where the aim is to foster independent thinking, reasoning, and the pursuit of the Good, no distinction exists between education, propaganda, and indoctrination in Communist regimes.17 In China, both of Mao’s pathways to reshaping the population consisted of a policy called “Szu Hsiang Kai Tsao,” or “ideological remolding.”18 While China vividly displayed this form of brainwashing in prison and labor camps, Beijing deployed the same strategy across all major institutions after the CCP took power.19 In comparison to the Soviet Union, the CCP heavily emphasized the ideological reshaping of the individual. Soviet propaganda efforts never sought the same psychological intimacy with its targets.20 In the 1950s, the psychiatrist Robert Lifton noted that when Westerners were taken prisoner by Communist officials in China, their understanding of Mandarin and Chinese culture was used against them during “reeducation.” 21

For the general population during the Maoist era, a standardized form of Mandarin comprised the main focus of China’s primary education.22 Political education and indoctrination saturated both elementary and higher education, with a particular emphasis being placed on cultivating loyalty to the CCP and anti-American attitudes among students.23 China’s Ministry of Education promoted indoctrination alongside “moral education” and an emphasis on the “five loves,” or key values to central to loyalty to the CCP. These “five loves” included: “love of the fatherland, love of the people, love of labour, love of science, and care of public property.”24

After taking power, the CCP restricted the availability of private education. Vestiges of classical Chinese education from before the Communist takeover were replaced with a state-driven focus on science and technology to advance industrialization.25 Within the CCP’s post-revolutionary college curriculum, “political education,” science, and technological training formed the core of university instruction.26

Language training, standardization, and indoctrination in China have been completely intertwined since 1949. Language teachers left over from China’s Republican Era were subjected to forced ideological reshaping, which occurred concurrently to the CCP’s formulating a literacy program aimed at advancing the “instruments of the proletarian political dictatorship for educating the people in Communist ideology.27

The re-training of China’s intellectual elite was one key to solidifying Communism as part of the country’s national identity. Portraying the takeover of the country by the CCP as “inevitable” lay at the center of a national narrative of class struggle.28 Over time, “moral education,” or the equivalent of a national ethos in Communist China, began to originate from the individual thoughts of the government’s top leadership.29 This top-down promotion of philosophy derived from China’s government elites used education as a conduit for sending propaganda into the broader population.30

Since taking power in 2013, Xi Jinping has continued this tradition with his own promotion of “Xi Jinping Thought,” which includes his personal philosophy of socialism and China’s economic development.31 This propaganda has permeated the Chinese government, the country’s state-owned enterprises, and China’s school system.32 Notably, Taiwan experienced the opposite of Beijing’s constructed top-down, ideologically-driven narrative. In Taiwan, democratization in the late 1980s fostered the Tai-yu language movement aimed at nurturing local identity.33

China’s “Confucius” Influence Strategy

A state-backed language program is useful to project propaganda at home and abroad. The political scientist Joseph Nye coined the term “soft power” to describe a country’s use of culture to obtain its goals.34 Language opens the door to culture, but goes deeper by offering completely new sets of meaning. British political scientist Steven Lukes theorized that power takes different forms, but can include decision-making power, agenda-setting power, and ideological power.35 “Ideological power” is where language offers a government the means to influence the worldviews of others.36 Language is a key benchmark of social identity.

For a government, a common standard language makes the world around it intelligible for the purposes of power projection. For example, a critical step for the formation of the modern Spanish nation-state consisted of Antonio de Nebrija’s publication of a standardized Spanish grammar in 1492. Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s revival of Hebrew from an ancient liturgical language to a modern one was central to the founding of Israel as a modern Jewish state. Knowledge of Mandarin outside of China offers Beijing communication on its terms in the realms of diplomacy and business. Additionally, Mandarin offers the CCP the means to promote its own ideological worldview. By teaching Mandarin abroad, Beijing can shape the worldviews of those future policymakers and elites most likely to work on China-related issues.

After the end of the Cold War, Beijing sought to promote China as a brand. Under Mao, China’s information operations centered upon exporting propaganda in support of overseas anti-colonial movements, and through channels of approved journalistic outlets.37 After the Tiananmen Square Massacre, China refurbished its information operations abroad by forming the State Council Information Office (SCIO) in 1991 in order to promote the PRC’s image.38 By the early 2000s, the PRC shifted to deploying Chinese culture for soft power and influence. CCs and CIs formed one element of this soft power offensive.

China’s use of the philosopher Confucius as the face of a soft power language initiative is ironic. Confucianism was the philosophical basis for the late Qing Dynasty. As a philosophy, it was Confucianism that China’s Nationalists and later Communists rebelled against.39 Confucianism and Chinese Legalism emerged as competing theories of statecraft in Ancient China, with the former focused on filial piety and benevolence.40 In contrast, the Legalists (c. 500 BC) asserted a logic of state based on the motto of fuguo qiangbing (“enrich the state and strengthen the military”), and the pursuit of power for its own sake.41

China has attempted to use Confucius as a cover for Marx in its soft power initiatives. In 2023, China clumsily attempted to combine Confucianism, Marxism, and Xi Jinping’s own brand of nationalism in a television show titled “When Marx Met Confucius.”42 While unpopular in China, the show illustrates attempts by Xi Jinping to promote Marxism as the “soul” of Chinese culture alongside “Confucianism as its root.”43 Notably, the series ominously ends with a warning of Beijing’s future retaking of Taiwan.44

The CCP uses Confucius abroad to promote its geopolitical agenda by portraying China in a positive light. A report conducted by University College Dublin in 2019 using geospatial targeting discovered that CIs led to a 6 percent improvement in rankings of China’s favorability in the surrounding community.45 Elsewhere, critics of the CCP note the irony of Beijing’s use of Confucius as a brand. In South Korea, Han Min-ho, president of Citizens for Unveiling Confucius Institutes, noted that “despite its title, there are no Confucian ideas whatsoever in the institute.”46

On the surface, CIs and CCs comprise little more than benign language programs funded by China for the benefit of colleges and schools abroad. However, leaders both in and out of China acknowledge their role as an instrument of influence. In 2009, Li Changchun, a member of the CCP’s Politburo Standing Committee, described CIs as “an important part of China’s overseas propaganda set up.”47 In 2020, US Secretary of State Michael Pompeo described CIs as a key aspect of CCP’s “propaganda apparatus.”48 Shortly thereafter, Under Secretary for the State Department, Keith Krach, wrote to college and university administrations across the US warning of the propaganda operation hidden within CIs .49

Language education is the focus of CIs and CCs; however, the Confucius brand extends beyond education. For example, Beijing created a “Confucius Peace Prize” in 2010 as a response to dissident Liu Xiaobo receiving the Nobel Peace Prize that same year.50 Under the auspices of China’s Ministry of Culture, and Beijing’s propaganda apparatus, the prize was administered by an intermediary front organization in order to “promote world peace from an Eastern perspective.”51 In this context, Beijing’s programs carrying a “Confucius” label can be identified as a propaganda operation

In 2017, the National Association of Scholars (NAS) began noting the risks CIs pose to American higher education. CIs were first overseen by China’s Ministry of Education through the Office of Chinese Languages Council, otherwise known as the Hanban.52 After NAS’s efforts brought public scrutiny to CIs, China defended itself by eliminating the tarnished Hanban label and by rebranding the bureaucracies overseeing them. The Hanban became the Center for Language Exchange and Cooperation (CLEC), with a subsidiary agency called the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF) tasked to oversee CIs and its related initiatives.53

At the university level, NAS investigations into CIs found the programs to be opaque. Contracts extended Hanban policies onto American college campuses, and were based upon Chinese law. Sensitive topics in the curriculum, such as the status of Taiwan, Tibet, and human rights in China, were muted. Portrayals of the CCP and Chinese government were whitewashed. At the same time, concerns over the risks posed by CIs to American national security were ultimately proven valid. At universities, CIs have been found to offer China proximity to research programs of military importance. For example, New York’s Alfred University hosted a now-closed CI and ran a Ceramic Engineering department that develops hypersonic missile technology for the United States military.54

From 2005-2017, over 100 CIs established operations at universities across the United States.55 Thanks to scrutiny from policymakers and the broader public, nearly all CIs have closed. Nine exceptions to this trend included those that have transferred to new universities, devolved to local nonprofits, or handed off to K-12 schools.56 As of 2017 in the K-12 level, approximately 500 CCs were operating in the United States.57 Globally at that time, China operated 1,074 CCs across 131 different countries.58

Figure 1.1: Confucius Classrooms Around the World (2017)59

|

Country |

Confucius Classrooms |

|

United States |

501 |

|

United Kingdom |

148 |

|

Australia |

67 |

|

Italy |

39 |

|

South Korea |

13 |

|

Thailand |

20 |

|

Germany |

4 |

|

Japan |

8 |

|

France |

3 |

In the United States, China oversees CIs through the Confucius Institute US Center in Washington, DC (CIUS). College-based CIs have traditionally served as the primary support program for CCs at the K-12 level.60 In August 2020, the US Department of State designated CIUS as a foreign mission in the US. The Center must now provide regular updates on the organization’s activities.61 According to the US Department of State, CIUS regularly received funds from the Hanban.62 CIUS social media accounts on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) have shown no new activity since the summer of 2021. The official website for CIUS, (http://www.ciuscenter.org/), is no longer active as of this writing.

While most CIs have closed, the total number of active CCs remains unknown. Despite this uncertainty, China-linked language programs persist around the country. PDE noted the survival of at least seven separate programs in American K-12 schools.63 China’s efforts to influence American children also include the use of China-owned social media platforms such as TikTok and other tech-based approaches to wage cognitive warfare.

Policymakers in the West have debated the TikTok threat, both in terms of data privacy and its role in assisting Chinese propaganda efforts. Last year, the Center for European Policy Analysis noted that TikTok’s algorithms are programmed to determine the virility of content posted on the platform and to determine what content gets suppressed or promoted.64 Even as Western skepticism over the app's safety led to increased calls to ban it, TikTok remains popular among teenagers, the same age demographic as students targeted by CCs.

CCs cannot be analyzed in isolation but must be viewed alongside the CCP’s other methods of influence.65 As schools shifted to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, Lingo Bus, a subsidiary of the CCP-linked company VIPkid, donated access to its Mandarin language platform to American K-12 schools.66 The platform’s content includes “military parades,” and a promotion of Xi Jinping as an influencer personality.67 At Cascade Elementary in Utah, a Mandarin teacher using this app integrated it into her overall course material. Zheng Yamin, a Mandarin teacher at the school, had her students write cards to Xi Jinping to celebrate the Lunar New Year.68 Surprisingly, President Xi wrote back with a promise to visit the school.69

Beijing’s interest in American education extends beyond its mainstream K-12 schools and universities. China has targeted private military academies and elite schools specializing in science and technology. In 2015, a Chinese nonprofit named the Research Center on National Conservation purchased the New York Military Academy for $15.83 million after outbidding another Chinese rival.70 Two years later, Florida Preparatory Academy, which hosts a Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps (JROTC) program for future US Air Force officers, was bought by a subsidiary of a Chinese company called the Newopen Group.71 Primavera Capital, a Chinese private equity firm, paid roughly $500 million to buy the Stratford School, a network of elite private schools in California.72 In this latter case, Chinese investors purchased the schools to help profit from Chinese students seeking admissions to American colleges and universities.73

In March of last year, Thomas Jefferson High School, an elite school in Virginia, received over $1 million from foundations and backers tied to the Chinese government and its United Front Work Department (UFWD).74 In 2020, the US Department of Defense noted that Tsinghua University, one of the top universities in China, was replicating Thomas Jefferson’s “model” of teaching in the PRC.75 Surveying China’s investments in US education indicates that Beijing is strategically targeting schools and universities to sway Americans and gain advatage.

The Relationship Between Confucius Classrooms and Confucius Institutes

Structurally, CIs in higher education have been a source of support and guidance for CCs at the K-12 level. American universities would partner with a Chinese counterpart university to form a CI, and that CI would, in turn, empower the creation and operation of CCs in surrounding K-12 schools. For example, China’s Capital Normal University formalized a partnership with the University of Buffalo (UB) in 2010 to establish a CI in New York State.76 The CI at the University of Buffalo then assisted in securing funding for a CC program at City Honors, a college preparatory school part of the Buffalo Public Schools system.77

City Honors, officially known as City Honors School at Fosdick-Masten Park, was named one of the top schools in the Northeast by the Washington Post in 2014.78 The CI at the University of Buffalo assisted with providing seed money and designating the school’s Mandarin program. City Honors received $25,000 in its first year in the program, with a noted annual and renewing stipend of $10,000.79 Dr. Jiyuan Yu, the Executive Director of the University of Buffalo’s CI, implied the political nature of the new CC program by stating:

And tomorrow we expect that you to become [sic] American ambassadors to China. To become top scholars in area of China studies to become great specialist [sic] in all areas of US-China relationships [sic] and make contributions to peace.80

The CI at the University of Buffalo oversaw the area’s CC program and regularly assessed the school’s performance.81 The University of Buffalo shuttered its CI in 2021.82 Between UB’s CI and its affiliated CCs, over 35,000 students in New York attended Mandarin courses through a Confucius program.83 Additionally, UB’s CI brought 42 teachers from China to CCs in the counties of Erie and Niagara.84 At City Honors alone, 300 students studied Chinese when the CC opened.85

Lew-Port High School, another Confucius Classroom, formalized its pre-existing relationship with a school in China by affiliating with the Confucius Institute at the University of Buffalo. When it opened in 2014, Lew-Port High School Principal Paul Casseri explained that the school’s CC designation was built upon a pre-existing partnership with Tianjin No. 2 High School in China.86 Rather than forge a new connection with China, Lew-Port’s CC status simply augmented what was already in place. UB’s CI director, Yu Yuan, noted that the CI would assist in securing textbooks and “computer equipment” for Lew-Port’s Chinese program.87

In the case of New York’s CCs, demand for Mandarin courses is likely due to organic appetite for the language at the K-12 level. Stephen Dunnett, Vice-President for International Education at UB, explained to the NAS in 2017 that a lack of funding from the state of New York was the primary motivation for the Buffalo school district to seek funding from China. Dunnett stated:

It’s shameful that the only way we can offer Chinese in the Buffalo school district—which is almost bankrupt—is that we have to ask the Chinese. It’s sad. Did we beg from France? Thanks to the Chinese taxpayers, 3,000 school children are learning Chinese. There is no way for them to learn Chinese if not for this program.88

Dunnett’s observations highlight why China’s Confucius Classrooms have been popular.

Several studies highlight the paltry state of foreign language enrollment across the American K-12 system. A 2017 study by the nonprofit Atlantic Council discovered only 20 percent of American K-12 students were enrolled in a foreign language course.89 Nationwide, only 11 states were found to have foreign language graduation requirements.90 A 2021 report from the Modern Language Association (MLA) found that foreign language enrollment in higher education fell from 2016 through 2021, with only American Sign Language, Biblical Hebrew, and Korean showing moderate increases in enrollment over that period.91

A lack of prominent, well-funded K-12 foreign language programs left the door open for China’s entry into the US education system. In 2015, US President Barack Obama announced the launch of a program called the “1 Million Strong Initiative” to encourage the study of Mandarin.92 This initiative, a program under the auspices of a nonprofit called the 100,000 Strong Foundation, was designed to increase the number of American students learning Chinese to 1 million by the year 2020.93 According to 2021 estimations by the Chinese language learning platform LingoAce, approximately 420,000 children in the US are studying Chinese.94 Using data from the American Councils for International Education, the US-China Institute at the University of Southern California (USC) found that just over 227,000 US K-12 students were enrolled in Chinese courses as of 2017.95 Chinese is not a popular foreign language choice among US students, frequently ranking below Spanish, French, and German while ranking slightly higher than Latin.96

Confucius Classrooms Compared to Other State-Backed Foreign Language Programs

Nations sponsor language programs abroad to exert cultural influence, soft power, and citizen diplomacy. Programs such as France’s Alliance Française, the United Kingdom’s British Council, Spain’s Instituto Cervantes, and Italy’s Societa Dante Alighieri all promote language learning abroad as a form of cultural diplomacy. What differentiates CCs from their counterparts is the direct and invasive involvement of the Chinese government.

NAS observed in 2017 that Confucius Institutes are embedded within universities, a clear distinction from European-sponsored language programs. One anonymous British professor noted that CIs offer Beijing a direct “platform to function in the university.”97 What separates China’s Confucius programs from other language initiatives is the top-down, contractual imposition of Chinese policy into the classroom.

Prior to the massive wave of CI closures across the US, American partner colleges were subject to upholding China’s interests. This was a contractual “obligation to uphold and defend the reputation and image of the Confucius Institutes,” under the threat of legal action.98 Contracts between China and their host universities enabled the Hanban to “sue directors or teachers in Confucius Institutes who develop lessons or lectures without clearing them with the Hanban first.”99 No such equivalent model of foreign government intrusion or assertion is known to occur with other foreign language programs.

Unlike China’s language programs, France’s Alliance Française and Germany’s Goethe Institutes constitute independent nonprofit organizations based within civil society. While these European programs do reflect their respective countries’ interests, they nonetheless remain distinct private actors. The disparity between China’s Confucius programs and language programs elsewhere is a product of China’s single-party dictatorship. Spain, France, and Italy are all democracies and promote their respective languages predominantly through independent networks of nonprofits.

In 2010, China’s minister of propaganda, Liu Yunshan, asserted the need for language programs to assist in fulfilling Beijing’s ideological missions abroad. In a 2010 People’s Daily article, Yunshan stated:

With regard to key issues that influence our sovereignty and safety, we should actively carry out propaganda battles against issuers such as Tibet, Xinjiang, Taiwan, human rights, and Falun Gong…We should do well in establishing and operating overseas cultural centers and Confucius Institutes.100

The Hanban and its later incarnations as the CLEC and CIEF are extensions of the CCP. On the surface, the Hanban, known also as the Office of Chinese Language Council International, operated as a nonprofit.101 However, the Hanban was overseen by Chinese government officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the State Press and Publishing Association, and the CCP’s propaganda agency.102 In 2019, China’s Vice-Premier, Sun Chunlan, offered the keynote address at a CLEC conference in Changsha about the need for Chinese language instruction before an audience of over 1,000 representatives from CIs based in 160 different countries.103 During her tenure promoting China’s Confucius programs, Sun Chunlan also served as the chair of China’s United Front Work Department (UFWD).104

The UFWD emerged out the CCP’s struggle for control of China in the 1930s and 1940s against the Japanese and nationalist Koumintang. Formalized in 1946 in the midst of the Chinese Civil War, the UFWD coordinates activities abroad to assist in furthering Beijing’s national interests.105 The UFWD is overseen by the CCP’s Central Committee and conducts influence operations both within China and abroad.106 Liu Yandong, the head of the UFWD at the time China launched the Confucius language programs in 2004, also served as the head of the Hanban in 2018.107 China’s Confucius programs are an extension of China’s state education system and are a clear tool used to achieve national aims in the United States. The next chapter outlines China’s strategy of using Confucius Classrooms to build ties with policymakers at the state and local levels.

Chapter 2: Confucius Classrooms in the United States

Confucius Institutes opened American universities to Beijing’s influence and policy. In turn, Confucius Institutes provided much of the structural support for the establishment of Confucius Classrooms in K-12 schools across the country. A staff report to the United States Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations stated that Beijing aggressively pursued the establishment of Confucius Classrooms, resulting in their exponential growth from 2009 into the 2010s.108 Rather than grow as an ancillary program to China’s better-known CIs, CCs are part of a broader strategy to influence American society and policymakers at the state and local levels.

In 2008, Xu Lin, then-counselor of the State Council of China, tasked US CIs with forming more CCs across the country.109 In a “Dear Colleague” letter to American CIs, the Hanban sought to collect information about the status of Mandarin language programs in the K-12 system.110 The Hanban sought information about state-level policies promoting Mandarin, the accreditation of “Chinese teacher’s certificates,” and the number of public and private schools incorporating Chinese into their foreign language curricula.111 Minutes from a 2011 CC conference in San Francisco acknowledge the attendance of “200 representatives from 150 operating Confucius Classrooms and 30 Confucius Institutes.”112

In that 2011 meeting, Beijing stated its goal of obtaining a central position within the US school system across multiple states with the blessing of state governments. Minutes from the CI conference, obtained by the US Senate, detail Beijing’s strategic objectives for targeting the American education system. The minutes state:

First, seek the top-down policy support from the state government, legislative and educational institutions, with a particular emphasis on access to the support from the school district superintendents and principles [sic]; second, to seek the recognition and support from parents and local community, as well as to inspire local demand and enthusiasm for Chinese language and culture learning, through various cultural activities and display of achievements of classroom instruction; third, to integrate the instruction of Chinese language and culture into curriculum [sic] of major subjects teaching taught in US K-12 schools, such as the ‘world culture’ and other courses, fourth, to create an effective communication mechanism with the local teach unions [sic] and the education administrators, as to create good [sic] environment for the living, cultural orientation and professional development for both the guest and local Chinese teachers, as well as promote the sustainable development of the Confucius Classrooms.113

The minutes demonstrate that the establishment of CCs forms one part of a broad Chinese effort to co-opt and leverage American institutions at the state and local levels. The Hanban’s stated goal of influencing education began with state governments and embraced teachers’ unions, school boards, administrators, and parents at the grassroots level. This indicates a “whole of society” approach to utilizing US institutions for its own purposes. In this light, CCs are a means for China to secure influence beyond education alone.

In 2017, China reiterated the role that CIs and CCs play in giving Beijing greater influence. In its annual report that year, the Hanban stated that CIs and CCs function as mechanisms to access broader segments of society in its host countries, and support Beijing’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative.114 The Hanban also explained that Mandarin instruction was ultimately aimed at accessing other subjects such as science and technology.115 The Hanban elaborated that CIs and CCs operate to build bilateral ties with state and local leaders beyond the domain of education. The Hanban stated that:

The Confucius Institutes all over the world actively offer Chinese and indigenous enterprises, social organizations and government sectors with language and professional training and actively take part in the cooperation between sister universities and sister states of both sides, and cooperation in economic and trade contact as well as people-to-people and cultural exchanges.116

China’s efforts to access local elites and businesses by leveraging CIs are not unique to the US. In Europe, China established Confucius programs intertwined with Beijing’s business interests. For example, former UFWD head Liu Yandong signed an agreement with France’s foreign minister to establish a “European Business Confucius Institute,” out of a partnership between the Hanban and Paris Ile-de-France Chamber of Commerce and Industry.117

Despite the closure or restructuring of most CIs in the US, relationships between US schools and the Chinese government not only continue but coincide with Beijing’s efforts to reinforce its use of education to strengthen the CCP’s reach. Often, these relationships grow from travel to China by American educators sponsored by Confucius programs. In October of last year, seven New York City K-12 principals traveled to East China Normal University on a taxpayer-funded trip facilitated by the China Institute.118

The China Institute, a New York nonprofit tied to East China Normal University, remains one of the holdout CIs in the US.119 This trip by New York educators coincided with the passing of a Chinese law designed to “enhance patriotic education.”120 Adopted on October 24, 2023, Beijing’s new education law mandates that teachers in the country “adhere to the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party,” and instill in their students a “love for the country, love for the Party, and the love of socialism.”121 For China, education secures both political and economic influence.

At the China Institute, the influence of ideology and business interests is evident in its language programs. The Institute’s “We All Live in the Forbidden City” program offers workshops for various grade levels throughout the 2023-2024 school year for Title I schools.122 Additionally, the Institute’s Chinese K-12 programs are partly supported by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, demonstrating Beijing’s interest in securing ties with state and local governments.123

Beyond language courses for K-12 students, the China Institute also offers courses and workshops for adults. The Institute similarly hosts lectures and networking events for business professionals. In October 2023, the Institute’s Executive Summit featured over 200 attendees to discuss US-China economic relations in light of growing geopolitical tensions.124 Last spring, the China Institute held a lecture titled “Mao and Markets: The Communist Roots of Chinese Enterprise,” which focused on the positive impacts of “Maoist ideology” on China’s economic growth.125

The China Institute’s friends also include private Chinese companies following the CCP’s “whole of society” influence campaign. Wanxiang America, a Chinese company, was one of many featured speakers at the China Institute’s Executive Summit.126 The company had previously offered financial assistance to the Confucius Classroom program in Chicago’s Public Schools. Chicago accepted the offer. Wanxiang America’s president Pin Ni signed an agreement with the then-Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel to support the city’s K-12 Chinese study abroad program.127 This plan, which covered students from 2017-2019, included a $225,000 grant in addition to subsidizing all of the costs for the participating students.128

As an auto parts manufacturer, Wanxiang has invested heavily in mid-western states by purchasing distressed assets from American automotive companies.129 The company’s reach extends to multiple states where it has promoted Chinese language programs. In 2015, then-Delaware governor Jack Markell signed an agreement with the Wanxiang Group to send students to study at the company’s Hangzhou plant as part of an intensive language program with professional development.130

The State of Delaware and Wanxiang penned a memorandum of understanding stipulating that partnership programs would center on language skills, science, “environmental protection and clean energy solutions.”131 These examples of Chinese non-profits and businesses hawking language instruction fall alongside China’s promotion of Confucius Classrooms to court economic benefits and politicians.

The exact number of Confucius Classrooms is unknown, and estimates vary. Many past estimations placed the number of CCs at 500.132 A 2023 study released by Parents Defending Education numbered CCs at a total of 143 “active and inactive” across 34 states and the District of Columbia.133 Our study found a total of 164 Confucius Classrooms not previously listed. This dataset was obtained from publicly available media reports and from other open sources in the United States and China. Our investigation discovered CCs at schools of various types. CCs were found across a spectrum of institutions that includes public school districts, single private schools, charter schools, and specialized community schools. The student population of these host schools also varies considerably.

Chicago Public Schools (CPS), which houses a CC in the form of its Chicago Chinese Language Center, is home to 330,000 students across 646 separate individual schools.134 In contrast, Wisconsin’s Verona Area International School is a public charter school with a small student body of only 120 students.135 While the 2023 report from Parents Defending Education highlights the proximity of CCs to US military bases, this report discovered that CCs follow a layered, “whole of society” targeting effort.

Figure 2.1: Confucius Classroom Host Schools

Figure 2.2: List of Known Confucius Classroom Programs

|

Name |

City or County |

State |

School Type |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Alexander Dawson School |

Las Vegas |

NV |

Private |

|

|

Anderson High School |

Anderson |

IN |

Public |

|

|

Anderson High School |

Austin |

TX |

Public |

|

|

Andover Public Schools |

Andover |

MA |

Public |

|

|

Arizona City Elementary |

Arizona City |

AZ |

Public |

|

|

Arlington Memorial High School/Battenkill Valley Supervisory Union |

Arlington |

VT |

Community |

|

|

Atlanta Public Schools |

Atlanta |

GA |

Public |

|

|

Bangor Chinese School |

Bangor Maine |

ME |

Misc. |

|

|

Barnard Mandarin Chinese Magnet School |

Point Loma |

CA |

Public |

|

|

Beechwood Independent School District |

Fort Mitchell |

KY |

Public |

|

|

Bentonville High School |

Bentonville |

AR |

Public |

|

|

Booker T, Washington High School |

Tulsa |

OK |

Public |

|

|

Boston College High School |

Boston |

MA |

Private |

|

|

Boston Latin Academy |

Boston |

MA |

Public Exam School |

|

|

Boston Renaissance Public Charter School |

Hyde Park |

MA |

Charter Elementary |

|

|

Boulder Creek High School |

Anthem |

AZ |

Public |

|

|

Brockton High School |

Brockton |

MA |

Public Option |

|

|

Broward County Public Schools |

Fort Lauderdale |

FL |

Public |

|

|

Brownsburg Community School Corporation |

Brownsburg |

IN |

Public |

|

|

Buffalo City Schools |

Buffalo |

NY |

Public |

|

|

Buncome County Schools |

Buncome County |

NC |

Public |

|

|

Canyons School District |

Multiple |

UT |

Public |

|

|

Carroll County Schools |

Carrollton |

KY |

Public |

|

|

Cascade Heights Public Charter School |

Clackamas |

OR |

Public Charter |

|

|

Castaic Union School District |

Valencia |

CA |

Public |

|

|

Cedarlane Middle School |

Hacienda Heights |

CA |

Public |

|

|

Chagrin Falls Exempted High School |

Chagrin Falls |

OH |

Public |

|

|

Charlotte County Public Schools |

Charlotte County |

FL |

Public |

|

|

Chicago Public Schools |

Chicago |

IL |

Public |

|

|

Clark County School District |

Clark County |

NV |

Public |

|

|

Cloverport Independent School District |

Cloverport |

KY |

Misc. |

|

|

Collegiate School |

Richmond |

VA |

Private |

|

|

Concord High School |

Concord |

NC |

Public |

|

|

Concordia Language Villages |

Moorhead |

MN |

Misc. |

|

|

Confucius Classroom at Central Carolina Community College |

Sanford |

NC |

Community College/Public |

|

|

Confucius Classroom at Chagrin Falls Exempted Village School |

Chagrin Falls |

Ohio |

Public |

|

|

Confucius Classroom at Columbus School for Girls |

Columbus |

OH |

Private |

|

|

Confucius Classroom at Dalton School |

New York |

NY |

Private |

|

|

Confucius Classroom at Germantown Academy |

Fort Washington |

PA |

Private |

|

|

Confucius Classroom at Hotchkiss School |

Lakeville |

CT |

Private, Preparatory |

|

|

Confucius Classroom at Lafayette School Corporation |

Lafayette |

IN |

Public |

|

|

Confucius Classroom at Paint Branch Elementary School |

College Park |

MD |

Public |

|

|

Confucius Classroom at the Academy of International Studies at Rosemont |

Norfolk |

VA |

Public |

|

|

Confucius Classroom at Washington Yuying Public Charter School |

Washington |

DC |

Public Charter |

|

|

Confucius Institute of Western Kentucky |

Multiple locations |

KY |

Multiple |

|

|

Consolidated School District 158 |

Huntley |

IL |

Public |

|

|

Culver Academies |

Culver |

IN |

Private |

|

|

Denver Confucius Classroom |

Denver |

CO |

Community College/Public |

|

|

District 742: St. Cloud, Minnesota Area |

St. Cloud |

MN |

Public |

|

|

East-West School of International Studies |

Queens |

NY |

Public |

|

|

Eastwood Knolls International |

El Paso |

TX |

Public |

|

|

Edward Bleeker JHS 185 |

Queens |

NY |

Public |

|

|

Enloe High School |

Raleigh |

NC |

Public |

|

|

Fairfax County Public Schools |

Fairfax Co. |

VA |

Public |

|

|

Falls Church City Public Schools |

Falls Church |

VA |

Public |

|

|

Fayette County Public School |

Lexington |

KY |

Public |

|

|

Fergus Falls High School |

Fergus Falls |

MN |

Public |

|

|

Fleming County Schools |

Fleming Co. |

KY |

Public |

|

|

Forest Hill Public Schools |

Ada Township and Cascade Township and Grand Rapids Township |

MI |

Public |

|

|

Francis Parker School of Louisville |

Louisville |

KY |

Private |

|

|

Gahanna-Jefferson School District |

Gahanna |

OH |

Public |

|

|

Garrison Forest School |

Owings Mills |

MD |

Private, All-Girls School |

|

|

Gavilan Peak School |

Anthem |

AZ |

Public |

|

|

Glastonbury Public School District |

Glastonbury |

CT |

Public |

|

|

Global Village Collaborative |

Thornton |

CO |

Language Immersion Charter School |

|

|

Greenwich High School |

Greenwich |

CT |

Public |

|

|

Grosse-Pointe Public School System |

Grosse-Pointe |

MI |

Public |

|

|

Hardin County Public Schools |

Hardin Co. |

KY |

Public |

|

|

Harrison County School District |

Harrison Co. |

WV |

Public |

|

|

Hazel Green school district |

Hazel Green |

WI |

Public |

|

|

Henderson County Public Schools |

Henderson Co. |

KY |

Public |

|

|

Heritage Hall School |

Oklahoma City |

OK |

Private |

|

|

Herricks Public Schools |

Hyde Park |

NY |

Public |

|

|

Highland Park Independent School District |

Dallas |

TX |

Public |

|

|

Hilltop High School |

Chula Vista |

CA |

Public |

|

|

Hopkins Public Schools/XinXing Chinese Immersion Program |

Hopkins |

MN |

Public |

|

|

Horseshoe Trails |

Phoenix |

AZ |

Public |

|

|

Houston Academy for International Studies |

Houston |

TX |

Public |

|

|

Huntley Community School District 158 |

Algonquin |

IL |

Public |

|

|

International High School at Sharpstown |

Houston |

TX |

Public Magnet School |

|

|

International School of Indiana |

Indianapolis |

IN |

Private |

|

|

International School of Portland Oregon |

Portland |

OR |

Private |

|

|

International School of the Americas |

San Antonio |

Texas |

Public Magnet School |

|

|

International School of Tucson |

Tucson |

AZ |

Private |

|

|

Jefferson County Public Schools |

Jefferson Co. |

KY |

Public |

|

|

Jonas Clark Middle School |

Lexington |

MA |

Public |

|

|

Kennedy High School |

Cedar Rapids |

IA |

Public |

|

|

Kettle Moraine High School |

Wales |

WI |

Public |

|

|

Kolter Elementary |

Houston |

TX |

Public |

|

|

Lake Forest High School District 115 |

Lake Forest |

IL |

Public |

|

|

Lawrence High School |

Lawrence Township |

NJ |

Public |

|

|

Lone Mountain Elementary School |

Cave Creek |

AZ |

Public |

|

|

Louisville Collegiate School |

Louisville |

KY |

Private |

|

|

LREI (Little Red School House & Elisabeth Irwin High School) |

New York |

NY |

Independent |

|

|

Medfield Public Schools |

Medfield |

MA |

Public |

|

|

Medger Evers College Preparatory School |

Brooklyn |

NY |

Public |

|

|

Minnetonka Public Schools |

Minnetonka |

MI |

Public |

|

|

Monongalia County Schools |

Monongalia Co. |

WV |

Public |

|

|

Montgomery County Schools |

Mount Sterling |

KY |

Public |

|

|

Natrona County High School |

Natrona County |

WY |

Public |

|

|

New Prairie Schools |

New Carlisle |

IN |

Public |

|

|

Norfolk Public Schools |

Norfolk |

VA |

Public |

|

|

North Attleboro High School |

North Attleborough |

MA |

Public |

|

|

North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics |

Durham |

NC |

Public |

|

|

Old Bridge School District Confucius Classroom New Jersey |

Old Bridge Township |

NJ |

Public |

|

|

Oldham County Schools |

Crestwood |

KY |

Public |

|

|

Oneida-Herkimer-Madison BOCES |

New Hartford |

NY |

Public |

|

|

Orange Unified School District |

Orange County |

CA |

Public |

|

|

Oxford Community Schools |

Oxford |

MI |

Public |

|

|

Oxford Hills Comprehensive High School |

Oxford County |

ME |

Public |

|

|

PA Sewickley Academy |

Sewickley |

PA |

Private |

|

|

Peddie School |

Hightown |

NJ |

Private |

|

|

Philadelphia Girls High School |

Philadelphia |

PA |

Public Preparatory |

|

|

Pioneer Valley Chinese Immersion Charter School |

Hadley |

MA |

Public Charter |

|

|

Piscataway High School |

Piscataway |

NJ |

Public |

|

|

Point Loma High School |

San Diego |

CA |

Public |

|

|

Prairie du Chien School District |

Prairie du Chien |

WI |

Public |

|

|

Renaissance Academy |

Lehi |

UT |

Charter |

|

|

Rhodes Junior High School |

Mesa |

AZ |

Public |

|

|

Riverview Elementary School and International Academy |

Lakeside |

CA |

Public |

|

|

Safety Harbor Middle School |

Safety Harbor |

FL |

Public |

|

|

Sammamish High School |

Sammamish |

WA |

Public |

|

|

San Diego Unified School District |

San Diego |

CA |

Public |

|

|

Sandwich High School |

East Sandwich |

MA |

Public |

|

|

Saylesville Elementary School |

Lincoln |

RI |

Public |

|

|

Seattle Public Schools |

Seattle |

WA |

Public |

|

|

Semillas Community School |

Los Angeles |

CA |

Charter |

|

|

Shaker Heights High School |

Shaker Heights |

OH |

Public |

|

|

Simpson County Schools |

Franklin |

KY |

Public |

|

|

Sisters School District |

Sisters |

OR |

Public |

|

|

Simsbury Public Schools |

Simsbury |

CT |

Public |

|

|

Snowden International School |

Boston |

MA |

Public |

|

|

South Kingstown Schools |

South Kingstown |

RI |

Public |

|

|

South Redford School District |

Redford |

MI |

Public |

|

|

St. Cloud Area School District |

Waite Park |

MN |

Public |

|

|

St. Louis University High School |

St. Louis |

MO |

Private School |

|

|

St. Mary Central High School |

Neenah |

WI |

Private |

|

|

St. Mary School, (Medford, Oregon) |

Medford |

OR |

Private |

|

|

Sumner County Schools |

Sumner Co. |

TN |

Public |

|

|

Sunrise Drive Elementary School/Catalina Foothills School District Chinese |

Tucson |

AZ |

Public |

|

|

Sunset Ridge Elementary Academy for Arts and World Languages |

East Hartford |

CT |

Public Magnet |

|

|

Syracuse Junior High School |

North Syracuse |

NY |

Public |

|

|

Tailwood High School |

Virginia Beach |

VA |

Public |

|

|

The Hill School |

Pottstown |

PA |

Private |

|

|

The Pingry School |

Bernards Township |

NJ |

Private |

|

|

The Roeper School |

Bloomfield Hills |

MI |

Private |

|

|

Thea Bowman Leadership Academy |

Gary |

IN |

Charter |

|

|

Tulsa Public Schools |

Tulsa |

OK |

Public |

|

|

Tyee Middle School |

Bellevue |

WA |

Public |

|

|

Verona Area International School |

Verona |

WI |

Public Charter |

|

|

Wake Technical Community College |

Raleigh |

NC |

Public |

|

|

Wardlaw-Hartridge School |

Edison |

NJ |

Private |

|

|

Washington Yu Ying Public Charter Elementary School |

Washington |

DC |

Public Charter |

|

|

Wayzata High School |

Hennepin County |

MN |

Public |

|

|

West Hartford public Schools |

West Hartford |

CT |

Public |

|

|

West Orange Public Schools |

West Orange |

NJ |

Public |

|

|

Westerly Public Schools |

Westerly |

RI |

Public |

|

|

William Winsor Elementary School |

Greenville |

RI |

Public |

|

|

Wilmar High School |

Willmar |

MN |

Public |

|

|

Winton Woods School District |

Cincinnati |

OH |

Public |

|

|

Winston-Salem Forsyth Schools |

Forsyth County |

NC |

Public |

|

|

YES Prep Brays Oaks |

Houston |

TX |

Public Charter |

|

|

Yinghua Academy |

Minneapolis |

MN |

Public Charter |

|

|

West Virginia Dept. of Ed. |

Multiple |

WV |

Public |

Structurally, CCs have often relied on a supporting institution in the form of a CI or independent nonprofit for funds and teachers. CI support for CCs blurs the line between the two due to the flow of resources that the K-12 schools have received. In a 2019 statement, Ohio Senator Rob Portman noted that in two separate audits of CIs, investigators from the US Department of State discovered over 30 instances of visa abuse in which Chinese teachers meant to be working at university-based CIs were actually found working in CCs.136 In these instances, the Department of State also discovered that CCs and CIs deliberately evaded investigators.137 Perhaps more concerning than visa fraud is the fact that the Federal government discovered that roughly 70 percent of programs that were investigated in this instance failed to disclose foreign financial aid that surpassed the mandatory reporting threshold of $250,000.138

Confucius Classroom Facilitators

Confucius Classrooms proliferated alongside Confucius Institutes, which have served as a main conduit of support and resources from the Chinese government. However, CCs have also relied upon a broader coalition of institutions and initiatives in the form of nonprofits, sister-city partnerships, and assistance from local policymakers and business communities. China’s Confucius programs demonstrate a multilayered approach to penetrate various layers of American education while also influencing the rest of society. The support for CCs derives from a number of actors and officials beyond the schools directly involved. Below is an examination of how these different actors have played a role in establishing and growing CCs across the United States.

Confucius Institutes

Confucius Institutes form the traditional backer for Confucius Classrooms. While the majority of CIs have closed, been transferred, or rebranded at their host universities, the relationships with the CCs under their tutelage warrant further examination in order to highlight how funds, personnel, and curricula have flowed from CIs to the K-12 system. Financially, CIs have typically supported CCs in the form of funds amounting to $10,000 per program, with the additional support of $20,000 in the form of learning materials.139

Operationally, CIs have managed many of the business and administrative aspects of the CCs at their affiliated schools. A Senate report by the Committee on Homeland Security Affairs discovered that budgetary oversight and accounting responsibilities for CCs often fell under the auspices of a supervisory CI.140 Within the school where the CC is hosted, oversight typically rests with the school’s principal or vice-principal with varying degrees of contractual autonomy.141 As CIs closed and shifted to new hosts, some constituent CCs have survived through a similar transfer to nearby school districts. Unfortunately, the investigation by the Committee on Homeland Security Affairs found that the Department of Education “does not conduct regular oversight of US schools’ compliance with required foreign gift reporting.142

In the United States, CIs first emerged in the early 2000s. The first American partnership started between the University of Maryland and China’s Nankai University.143 In exchange for hosting the CI, the University of Maryland accepted teachers from Nankai and ceded approval over the CI’s actions to the Chinese government.144 The amount of Chinese funds for the University of Maryland was substantial, and it was included in a 2015 agreement in which the university agreed to dedicate an official university building to the program in exchange for $900,000.145 After the University of Maryland announced its withdrawal from China’s Confucius program, it returned all funding to Beijing.146 Paint Branch Elementary, a high-performing elementary school in College Park, Maryland, partnered with the University of Maryland’s CI in an effort to internationalize its curriculum.147

In 2010, Paint Branch Elementary principal Jay B. Teston noted that one of the goals of the school was to build “international education” and “go deeper into our projects involving Chinese language and culture.”148 Teston’s motivations echoed those of Maryland’s CI director, Alan Chung, who stated that mastery of Mandarin was helpful for students “in a global society.”149 It is critical to note that the partnership between Paint Branch Elementary and China was not restricted to the CI at the University of Maryland. Paint Branch also had a partnership with Nankai University’s own elementary school in Tianjin.150 This bilateral K-12 partnership included opportunities for student travel to China.151

The prominence of the CC at Paint Branch quickly grew after its founding. By 2012, the school boasted a Chinese immersion program under the auspices of its partnership with the CI at the University of Maryland.152 That year, 15 students from the school traveled to China, while students from its own Nankai partner school visited Paint Branch Elementary.153 The immersion program at the school began with kindergartners, and included the parallel teaching of other subjects within both Mandarin and English through the sixth grade.154 Notably, the school’s language lab was also a recipient of $25,000 in the form of a state grant for teaching Mandarin.155 In media coverage of the Paint Branch program, the Washington Post noted the prominence of PRC flags within the classroom. As national criticism of CIs grew, so did criticism of CCs. At Paint Branch, one critic noted her concern over the travel component of the program, and young students being exposed to a “collectivist view as opposed to an individualist view” at such a young age.156

Partnerships between K-12 schools and China sometimes grew independently but concurrently with established CIs. Atlanta Public Schools (APS) began its CC initiative alongside the founding of the CI at Emory University through its partnership with Nanjing University.157 The Emory-APS partnership (also known as the Confucius Institute in Atlanta) was designed to be a Georgia-wide “regional Center for Chinese teacher training and Chinese instruction” to “pool together China specialists in universities in the Atlanta area.”158

At its opening, the CI in Atlanta foreshadowed the 2011 plan outlined by China to normalize Confucius programs across the United States. The Confucius Institute in Atlanta stated its intent to expand beyond the confines of academic institutions in order to offer its language courses to the broader public. It sought to act as a model for Mandarin programs across Georgia, and to offer “classes in language and culture geared toward Atlanta’s business community, teachers, parents, and the public.”159 The Emory-led partnership ended in 2021.160

Major metropolitan areas with large school systems are attractive targets for China’s influence operations. As of 2023, APS had a student body of roughly 50,000 students across 59 “neighborhood schools,” “5 partner schools,” and 19 charter schools.161 Chicago Public Schools (CPS) dwarfs APS with its student population of roughly 330,000 students across 646 separate schools.162 The CC at CPS is still in operation following the replacement of its host CI program in 2020 and was rebranded as the Chicago Chinese Language Center.163 CPS opened its CC through a partnership with the Hanban and Shanghai East China Normal University in 2006. It also has the distinction of being the first CI “housed in a K-12 environment.”164 In other words, the CI and CC in Chicago schools have been the same program.

The CC at CPS emerged out of a pre-existing Chinese language program that was first formed in 1999 with a small cohort of 3 schools.165 Over time, this Chinese language program grew to encompass 13,000 students learning Chinese from elementary to high school.166 Chinese is now among the top three foreign languages studied across Chicago schools.167 The prominence of the CC at CPS is demonstrated by its inclusion in a network of collaboration that includes such organizations such as the Asia Society, Chicago Sister Cities International, the Chicago mayor’s office, the College Board, the State Illinois China Office in Shanghai, the US-China Strong Foundation, and the US Department of State.168 In this light, Chicago’s CCs offer an example of China’s Confucius strategy in action due to its inclusion of state and local policymakers, nonprofits, and a prominent position among the Chicago public.

At least some of the Mandarin teachers in the CPS program are home-grown and come from within the district. CPS sought out Chinese speakers already working within local schools and assisted them with obtaining the certifications they needed to instruct language courses.169 Lacking a deep enough bench of Mandarin speakers to meet demand, CPS reached out to colleges and universities to assist with teacher training and certification.170 Students from the CC have also traveled to China for month-long intensive programs under the auspices of the “100,000 Strong Initiative,” which began in 2009 with the help of the Obama administration.171 Under its new name, Chicago Chinese Language Center, Chicago’s CCs remain in operation.172

Some CCs began as CIs handed off to local schools as they closed. The CI at Western Kentucky University (WKU) shuttered in 2019, only to be transferred to nearby schools at the Simpson County School District.173 The Simpson County Schools CC demonstrates not only the relationships between university-based CIs and their K-12 offshoots but also how the survival of Confucius programs is facilitated by actors from private businesses and nonprofits.

WKU’s CI was formed in 2010 out of partnerships with the Hanban, North China Electric Power University (NCEPU), and Sichuan International Studies University.174 Article 11 of the agreement penned between WKU and its Chinese partners notes Beijing’s authority over “textbooks, pedagogy and academic research.”175 The founding of the CI at WKU is closely connected to the creation of CCs across the state of Kentucky. Amy Eckhardt, the CI’s US co-director at the time, noted that the institute would serve K-12 schools in Warren County as well as the university.176 Eckhardt’s description of WKU’s CI reflects the goals stated by Beijing in 2011 in its effort to use them to influence different levels of American society.

In describing the founding of the CI at WKU, Eckhardt noted that the institute:

Engages in outreach to local educational institutions, businesses, government and community members, building partnerships with educational and community organizations to offer cultural programming, language education and K-12 summer programs and partnering with local businesses to offer cultural and language training.177

WKU’s CI proved so successful in its outreach that it won awards in 2013 and 2015 for having the most “Advanced Confucius Institute of the Year.”178

The outreach of WKU’s CI into Kentucky’s K-12 system pre-dated its formal handoff and transformation into a CC. Wei-Ping Pan, the WKU’s CI director in 2011, outlined a number of goals for the program’s growth. Pan’s goals for the program included achieving a yearly 10 percent increase in Chinese language enrollment.179 WKU’s CI obtained a recreational vehicle to serve as a “modular unit” that it could use to hold events at local schools, host workshops, and engage communities beyond the confines of its university campus.180 In the 2012-2013 school year, 17 of the 33 Chinese teachers at the WKU CI who came from the Hanban secured licenses to teach from the Kentucky Educational Standards Board.181 The following year, another 10 Hanban teachers obtained K-12 teaching credentials.182

Elsewhere in the state, the University of Kentucky’s CI worked to meet the state’s demands for Chinese teachers in school systems. Called the “K-12 Chinese Language, Culture Development and Enhancement Program,” the CI at the University of Kentucky allowed the state’s schools to obtain teachers from the Hanban for periods of up to three years.183 The Hanban was responsible for the recruitment of the teachers, as well as for their yearly salaries.184 One principal in Kentucky’s Woodford County stated that the program “builds ownership for our Chinese teachers and that spills over to enhanced instructional experiences for our students.”185

In the case of WKU’s CI, its outreach into surrounding schools proved essential to its survival, as it laid the groundwork for quick rebranding without major interruption. WKU withdrew from its agreement with China in April 2019. Three months later, Simpson County Schools had signed an agreement with the Hanban. Simpson County Schools then announced its intention to expand the Hanban-linked program to teach 22,000 students across the state.186 Bureaucratically, this initiative included 47 separate K-12 schools, and involved a “transfer of assets” from the CI to the new CC in the form of “vehicles, furniture, instructional materials,” and a sum of $192,714.25.187

Funds and learning materials were not the only aspects of WKU’s CI that made their way to Simpson County Schools. The leadership of both the CI and its CC offshoot transferred to the other. This transfer included a new contract agreement overseen by a consulting firm called BG Education Management Solutions, which was run by the former CI director.188 Terrill Martin, the CEO of BG Education Management Solutions, served as WKU’s CI director prior to its closure.189 BG Education Management Solutions describes itself as a nonprofit “designed to recruit foreign language teachers who work in local K-12 schools,” and works to bring teachers from abroad to the US.190 NAS noted in its 2022 report on CIs that BG Education Management Solutions registered a “Doing Business As” entity in the State of Kentucky to operate as the Confucius Institute at Western Kentucky (CIWK).191 Because of the nonprofit’s involvement, China retained its regional presence in western Kentucky.

In 2021, CIWK declared that it desired to “increase its footprint of Chinese language” through outreach to “private schools, independent school districts, and some districts the institute has lost.”192 For the 2021-2022 school year, CIWK obtained 15 teachers from China who came from WKU’s old CI partner at NCEPU.193 Even two years after WKU’s CI closure, NCEPU was the main source of teachers that connected CIEF to Kentucky schools via BG Education Management.194 Financially, the amount of funds Kentucky schools have received from China have been considerable. By its own accounts, BG Education Management Solutions received $948,462 from CIEF in 2020.195