Introduction

A movement focused on persuading college trustees to sell off institutional holdings in coal, oil, and gas might sound like a minor trend. Students protest things all the time, many of which do not register as significant social, political, or economic causes. Free Mumia. No nukes. Ban GMOs. Calling for fossil fuel divestment does not, at first, sound like a cause that has the moral urgency of the Civil Rights movement or the effort to end apartheid in South Africa.

But in fact the fossil fuel divestment movement is something to take seriously. Not because it threatens the supply of capital to energy companies. It doesn’t. Not because it threatens to bankrupt colleges. It doesn’t do that either. What this movement does do, however, is impress on a whole generation of students an attitude of grim hostility to intellectual freedom, democratic self-government, and responsible stewardship of natural resources. This study shows how that is happening.

The fossil fuel divestment movement traces to a small but loud group of professional activists. Their campaign is amply financed. The Rockefellers, the Schumann Media Center, and Tom Steyer, the hedge fund billionaire who spent millions trying to put climate change on the 2014 electoral map, have done their part. More than a thousand petitions and campaigns appear on an interactive map at GoFossilFree.org (Go Fossil Free declined to give an exact count), up from a single campaign in 2010 and about 100 at the end of 2012. Many of those petitions are signed by fewer than 100 people—some by only one or two. But the movement more than makes up in boast what it may lack in grassroots support.

The Guardian, paraphrasing research from Ben Caldecott, director of the Stranded Assets Program at Oxford University’s Smith School, says this movement is “the fastest growing divestment campaign in history”1—although recent divestment campaigns, with the exception of the “Boycott/Divest/Sanction” movement against Israel, have not achieved national traction, and the one previous major divestment movement, against South African apartheid, grew gradually over a decade. An investment firm, Arabella Advisors, claims fossil fuel divestment has grown fifty-fold in the last twelve months, on the grounds that the net wealth of the institutions and individuals that divested has multiplied by fifty since Arabella last calculated in fall 2014.2

On colleges, small numbers of students run vociferous campaigns focused on publicly shaming those who disagree. Often this means marching around campus and into board meetings and tweeting aggressively. Their self-avowed strategy is to intimidate the uncommitted into joining, or at least not opposing, divestment. Student activists admitted to us in interviews that though they could convince a majority of the student body to vote for divestment resolutions or sign petitions for divestment, only a small minority actually “believed in” divestment. These activist students have learned political history. A minority of indignant and dedicated special interests can prevail in the democratic court of public opinion by bullying opponents and polarizing what were once straightforward pragmatic questions. Fossil fuel divestment is a special interests campaign that punches above its weight.

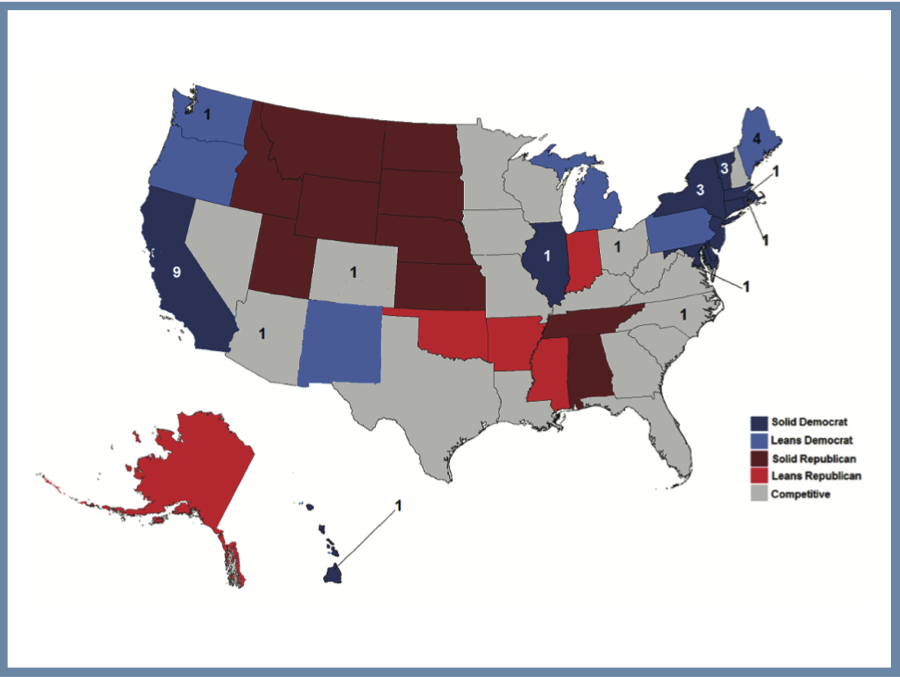

The fossil fuel divestment movement bluffs in other ways. It claims power to stop global warming and improve the environment. It can fulfill neither. Fleeing financial investments in an industry leaves those investments available to others. It does not reduce consumption of the fossil fuels divestment activists hate. It does not alter the business model of fossil fuel companies, who have no incentive to heed ex-investors. At most, divestment can build blocs of single-issue climate voters who dogmatically support measures that, in theory, might meet those goals. But that is not the same thing—and it is risky to bet that it will lead to the same place. Self-avowed environmentalists have rejected divestment as an unhelpful “distraction,”3 a “misguided” ploy,4 and a “diversion.”5 Its shrill fossil fuel-free puritanism will only “play into and exacerbate the ideological divide and political polarization” currently surrounding environmental policy, says Robert Stavins, the Albert Pratt Professor of Business and Government at the Harvard Kennedy School and a lead author on the third, fourth and fifth assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.6

The fossil fuel divestment campaign is more than a foolish distraction from environmental conservation. It represents an affront to academic freedom and the purpose of higher education, and an assault on the heritage of American political theory. Advocates of fossil fuel divestment sidestep real debates about energy and environmental policy and scorn discourse as needless delay. The campaign smears opponents and bullies dissenters. It treats colleges and universities primarily as instruments of political activism and only secondarily, or even thirdly or fourthly, as places that exist to teach knowledge and pursue truth.

The fossil fuel divestment campaign also denies the merits of an American-style representative democracy. The central premise of the campaign is that the political system is so indissolubly wedded to the fossil fuel industry that government action on environmental policy is illegitimate. That premise casts anyone who disagrees with divestors as a mercenary of the fossil fuel industry and litters with political landmines the grounds for legitimate debate. It asserts that mob rule by street-marching activists is better than representative democracy, and that the tradition of civic debate is a hopeless waste of time.

That is what makes fossil fuel divestment dangerous. The movement, apart from its impotence to improve the environment and its failure to convince most college trustees of divestment’s value, trains a generation to disdain representative government, wish away the energy needs of a modern economy, and replace a college education with four years of misguided activism.

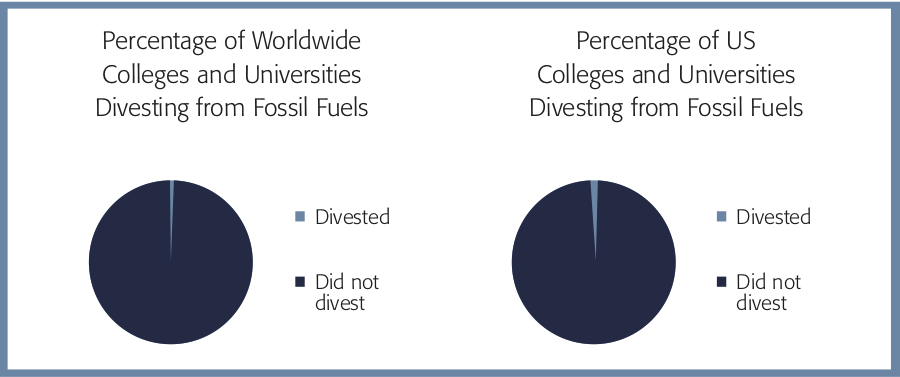

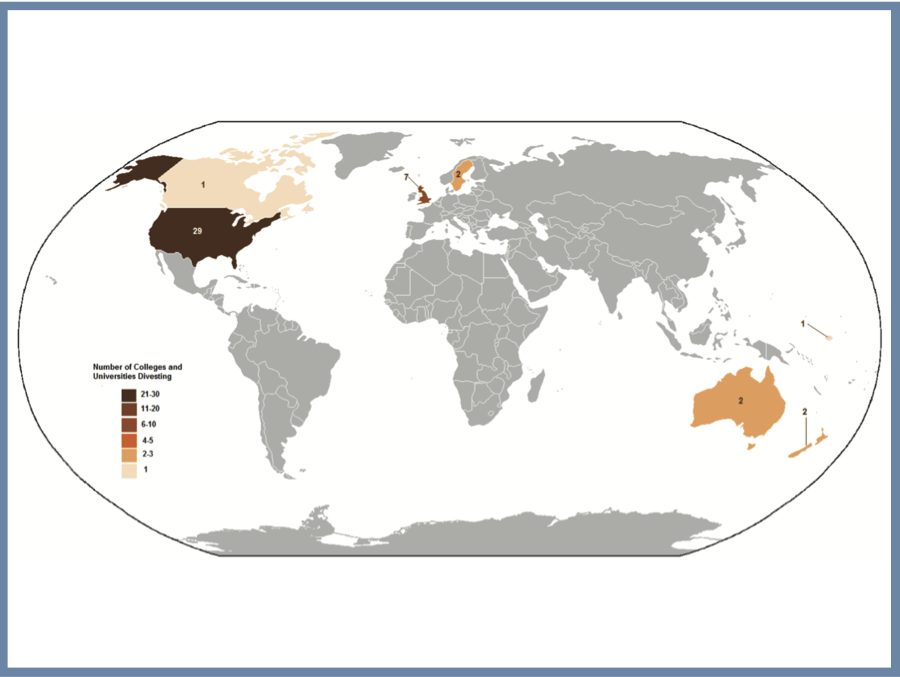

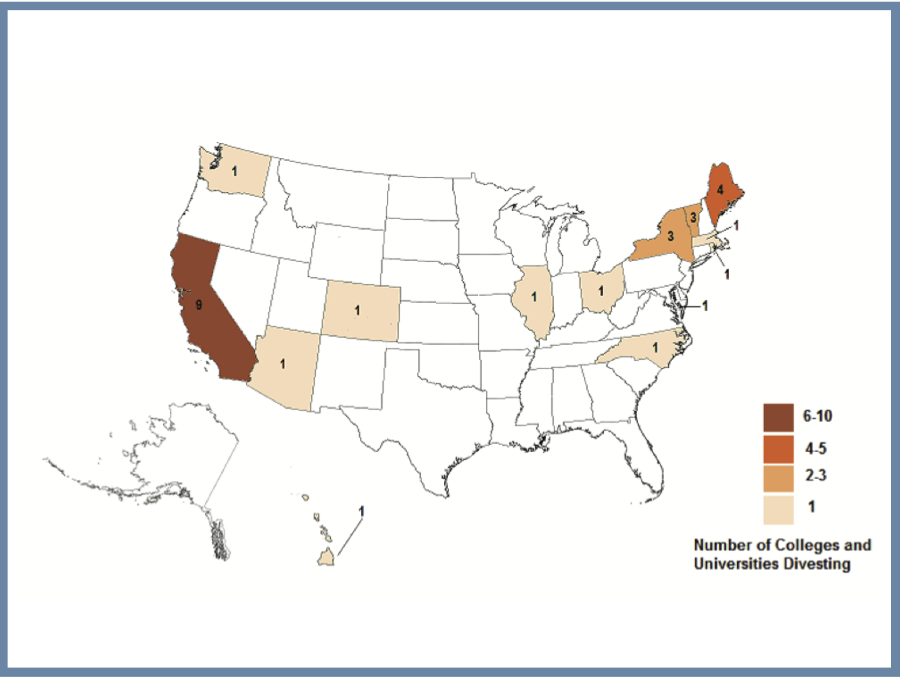

This report offers a history and analysis of the fossil fuel divestment movement, concentrating on American colleges and universities. The campaign began at a small college near Philadelphia. Early divestors were colleges and universities in the northeastern United States. The vast majority of the educational institutions that have taken divestment pledges are in the United States. Even as the campaign has grown to other institutions in other parts of the world, its advocates remain dominated by students. We offer a perspective that sees through the oversized projections the divestment movement has cast of itself. We also offer the most extensive encyclopedia of college fossil fuel divestment campaigns published to date. We are not activists, though, and we offer a platform to both sides of the divestment debate. Or rather, because policies are always nuanced and rarely fit into simple yes-or-no categories, we present a sampling of the sides to this divestment polygon. At the end of this report, we include short essays from scholars and thinkers who have a variety of ideas worth considering. These include Bill McKibben, the architect of the fossil fuel divestment movement; Viscount Matt Ridley, a scientist and popular science writer; Willie Soon, an astrophysicist, and Lord Christopher Monckton, an environmental policy expert; Alex Epstein, author of The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels; and William M. Briggs, a statistician. The sampling would be broader still, had not some advocates of divestment declined to participate.

Divesting fossil fuels, say those who support it, means getting on the right side of history. History is not a force and it does not take sides, though we can, of course, learn from past mistakes. In the tradition of recording the past in the hopes that others can learn from it, we offer the following history and analysis.

Chapter 1: Going Fossil Free: A History of the Fossil Fuel Divestment Movement

Late in 2006, a handful of students at Vermont’s Middlebury College sat down to plan life after graduation. They created three transparent maps of the United States. One charted coal mines. Another showed places with potential for wind energy. The third displayed regions with excellent craft beer. The syzygy spoke. They would move to Montana.7

Most of them had come to Middlebury interested in environmental advocacy. May Boeve, who graduated in February 2007, had grown up selling lemonade for PETA fundraisers.8 In early 2005, after some of them took a winter-term course called “Building the New Environmental Movement” with environmental economist Jon Isham, they had helped organize a conference, MiddShift, that persuaded Middlebury to eliminate all greenhouse gas emissions. (The college is slated to meet that goal next year, in 2016.9) Their club, the Sunday Night Group, became what Isham called “the heartbeat of climate activism on this campus.”10 Now they wanted to boost the heart rate of the national environmental movement.

Before they headed west, another Middlebury professor approached them about helping him with a project. His name was Bill McKibben, and he was a visiting scholar of environmental studies. McKibben wanted to organize a day of climate action, with people around the country marching to call on the government to thwart climate change. He needed help coordinating the demonstrations. Were they interested?

They were. They cancelled the trip to Big Sky Country. Instead, with McKibben, they founded Step It Up. On April 14, 2007, the Step It Up National Day of Climate Action counted 1,400 distinct protests, each with banners that said, “Step It Up, Congress: Cut Carbon 80% by 2050.” Congress did not cut carbon by 80 percent, but the Middlebury team persevered. In 2008, Step It Up grew into two organizations, 1 Sky in the United States, 350.org everywhere else. By October 2009, just before the December UN Framework Convention on Climate Change meeting in Copenhagen, 350.org organized another, even larger, set of simultaneous protests: 5,245 groups in 181 countries.

The Copenhagen talks melted into flimsy promises that disappointed every environmentalist. The Swedish Environment Minister Andreas Carlgren called it a “disaster.”11 The Copenhagen accord brokered by President Barack Obama and Chinese premier Wen Jiabao officially recognized the dangers of the climate warming beyond 2 degrees Celsius, but asked signatory nations merely to promise to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to a level compatible with that temperature rise. The Copenhagen accord provided no enforcement machinery.

Government inaction in the next two years persuaded Bill McKibben that 350.org needed a new strategy. Previously, his approach “had been pretty much the same as everyone else’s: go through the political system,” McKibben recalls in his book, Oil and Honey.12 But fossil fuel companies whose products caused climate change had lobbied and “schemed endlessly” to keep the political system from acting. What if the political system was the wrong target? “I had an idea—that we needed instead to go straight at the fossil fuel industry,” McKibben recalled.

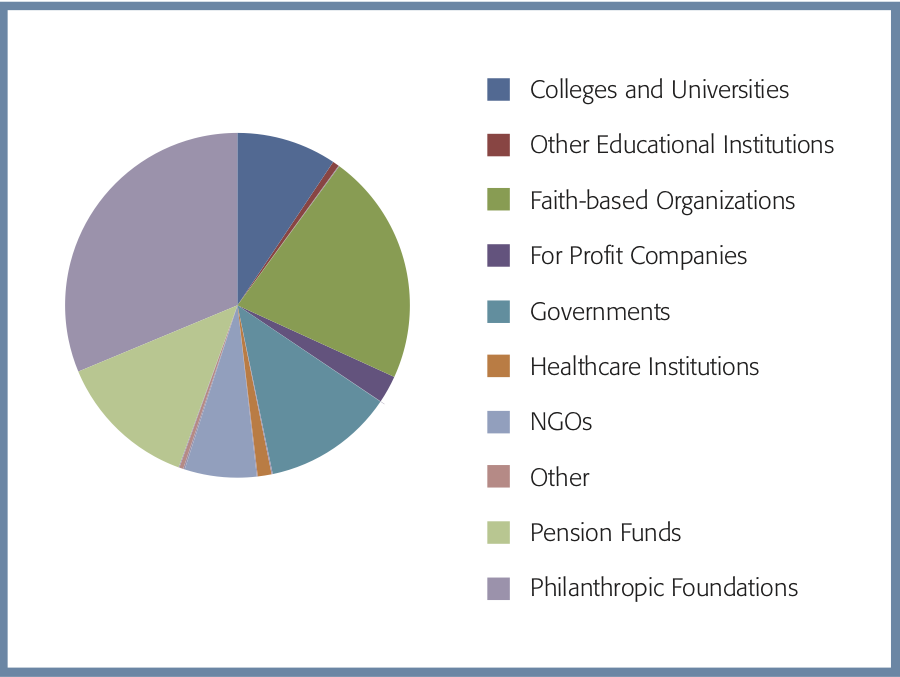

McKibben’s weapon of choice was a campaign to disinvest from fossil fuel companies. Cut investments in the industry, stigmatize its practice, and make it unfashionable to associate with or accept donations from fossil fuel corporations. Fast forward a few years, and fossil fuel divestment, especially popular among youth, is now the fastest growing student movement. Three hundred forty-eight institutions have divested. These include the Rockefeller Brothers Fund (legatees of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company); the $9 billion Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund (which got its money from Norwegian oil); and the World Council of Churches. Oxford University divested, as did Stanford. So did Georgetown University and Pitzer College.

In a May 2014 article for the Guardian, Christiana Figueres urged faith leaders and others to “find their voice on climate change,” and encouraged them to consider divesting.13 Figueres, who watched the Copenhagen “disaster” in 2009 as a Costa Rican negotiator, is now executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. She will oversee the next round of climate negotiations, scheduled for December of this year.

Do the Math

The fossil fuel divestment movement first erupted in 2012, when McKibben published the article “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math” in the August edition of Rolling Stone. It went viral. McKibben had taught part-time at Middlebury since 2001, but his background was in writing. He edited The Crimson his senior year (1982) at Harvard and spent five years writing “Talk of the Town” for the New Yorker before leaving to work in environmental advocacy.

“To grasp the seriousness of our predicament, you just need to do a little math,” McKibben explained in Rolling Stone. Having “reasonable hope” of staying beneath 2 degrees of warming required emitting no more than 565 gigatons of carbon dioxide. Fossil fuel companies had in their reserves enough to emit 2,795 gigatons—five times more. The environmental movement had struggled to coalesce into a politically powerful force, McKibben said, because it lacked a common goal: “A rapid, transformative change would require building a movement, and movements require enemies.” Who was the enemy? McKibben’s math gave him the answer:

What all these climate numbers make painfully, usefully clear is that the planet does indeed have an enemy – one far more committed to action than governments or individuals. Given this hard math, we need to view the fossil-fuel industry in a new light. It has become a rogue industry, reckless like no other force on Earth. It is Public Enemy Number One to the survival of our planetary civilization.14

That collective Public Enemy Number One came with an outline of As, Bs, and Cs beneath. Rex Tillerson, the CEO of Exxon, came out on top of the list: he planned for Exxon to spend $37 billion a year for the next four years searching for oil and gas: “There’s not a more reckless man on the planet than Tillerson.” Charles and David Koch, libertarian philanthropists and owners of Koch Industries, immorally planned to “lavish” up to $200 million on the 2012 election. Not even the US Chamber of Commerce escaped McKibben’s ire. The Chamber had spent 90 percent of its political spending on Republicans, “many of whom,” McKibben alleged, “deny the existence of global warming.”

There were other reasons to take down the fossil fuel industry, besides the convenience of marking out a clear enemy. Slimming down our consumption of fossil fuels would help, but “At this point, effective action would require actually keeping most of the carbon the fossil-fuel industry wants to burn safely in the soil, not just changing slightly the speed at which it’s burned.” Putting a price on carbon was important, but how could Congress ever enact such a pricing scheme when the fossil fuel industry lobbied so hard against it? McKibben thought divestment could change that.

McKibben’s source for his math was a November 2011 report from the Carbon Tracker Initiative, a London group of environmentalist financial analysts who came up with the concept of a “carbon bubble.”15 Staying below a 2-degree rise in temperatures meant leaving 80 percent of fossil fuel reserves in the ground, stranding the majority of the corporations’ assets.16

With strobe lights and a rotating line-up of musicians and minor celebrities, upwards of a thousand attendees packed into auditoriums. Charismatic, fist-pumping McKibben took center stage as the “talks” took on the verve of a rock concert.

The report didn’t specifically recommend investor action of the type McKibben suggested, but lead author James Leaton did suggest that financial regulators “do the maths” (British style) and “assess” the risks of the bubble. He urged regulators to “send clear signals” for corporations to “shift away from the huge carbon stockpiles” for the sake of the climate and their investors. “This is the duty of the regulator – to rise to this challenge and prevent the bubble bursting,” the report admonished. Of course, the possibility of a burst bubble assumed that governing agencies would restrict the extraction and use of fossil fuels in the first place, which is precisely what McKibben’s campaign hoped to achieve.

A few months after his terrifying math went viral online, McKibben biodiesel bused his way to 21 cities in a nationwide speaking tour called “Do the Math.” He began in Seattle and wound down to Los Angeles, cross-country to Chicago, Columbus, Madison, Minneapolis, Boston, Philadelphia, Omaha, Boulder, and more. For those too far away, 350.org developed a “Do the Math” movie.17 The kit came complete with schoolroom-esque banners. One showed the equation, CO2 + $ = a flaming earth. Another proclaimed, “WE > FOSSIL FUELS.”

With strobe lights and a rotating line-up of musicians and minor celebrities, upwards of a thousand attendees packed into auditoriums. Charismatic, fist-pumping McKibben took center stage as the “talks” took on the verve of a rock concert. Desmond Tutu, the South African archbishop and Nobel Peace Prize recipient who blessed the 1980s divestment movement for helping to end apartheid, made an appearance. So did Naomi Klein, McKibben’s colleague and a bestselling author. Klein’s background was in labor activism, and her previous books, No Logo, Fences and Windows, and The Shock Doctrine, castigated global corporations and the rise of capitalism.

With strobe lights and a rotating line-up of musicians and minor celebrities, upwards of a thousand attendees packed into auditoriums. Charismatic, fist-pumping McKibben took center stage as the “talks” took on the verve of a rock concert.

McKibben’s Rolling Stone article mentioned the word “divest” only in the context of a historical example, the 1980s apartheid divestment. But the lecture tour was more explicit. McKibben asked crowds to start local divestment campaigns, and to push their colleges, churches, charities, and pension funds to cancel endowment holdings in the top 100 oil and top 100 coal companies, identified in a list drawn up by the Carbon Tracker Institute.

The first crowd gathered on November 2nd, in Seattle, Washington. On the 5th, Unity College president Stephen Mulkey announced from Vermont that his college would divest from fossil fuels.18 By the end of November, 350.org announced it had started 100 divestment campaigns.19 350.org estimated at the end of 2014 that 1,162 divestment campaigns have been launched since 2012.20 Many are shepherded by paid 350.org staff; organized by 350.org-trained (and sometimes paid) students; use 350.org materials, press databases, and templates; and are hosted on the 350.org daughter site GoFossilFree.com.

350.org is now one of the world’s most visible environmentalist grassroots groups. It has organized hundreds of thousands of protests. It has 94 full-time staff in 15 countries21 and an army of thousands of volunteers in nearly every other. Named for what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change deems a safe number of carbon dioxide parts per million of molecules in the atmosphere, 350.org is the face of the international climate movement.

It also has as its leader one of the best-recognized faces of the environmental movement. In 1989 Bill McKibben wrote the first popularizing book on global warming, The End of Nature. A decade later he wrote Maybe One: The Case for Smaller Families (1999), and his Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future (2008) argued against growth as the measure of economic wellbeing. In Eaarth: Making a Tough Life on a New Planet (2011), McKibben postulated that ecological damage had so changed the planet it needed a new moniker (hence the extra “a”). Another eleven books tackled similar themes.

350.org’s student founders remain at the center of the organization. May Boeve is executive director; Jamie Henn, Director of Communications and Strategy; Phil Aroneanu, US Managing Director; Will Bates, Global Campaigns Director; Jeremy Osborn, Operations Director. All graduated from Middlebury College between 2006 and 2007. Another three “Midd Kids” helped get 350.org off the ground but aren’t official co-founders: Jon Warnow, now 350.org’s Web Director, Jason Kowalski, Policy Director, and Kelly Blynn, who was Global Campaigns Co-Director until she left 350.org in May 2012. Blynn now manages a campaign to shift government funding away from highways and toward public transit and pedestrian and cyclist improvements. The distinction predates 350.org’s existence. The five “official” co-founders worked with McKibben on Step It Up’s first campaign back in April 2007; Warnow, Kowalski, and Blynn joined Step It Up in August of that year. Three months later, in November 2007, all eight students and McKibben helped Step It Up through its transition into 1 Sky and 350.org, and three years later all eight again worked to rejoin 1 Sky and 350.org.

Divestment is not 350.org’s first try at making political theater out of a non-issue. In 2011, it drummed up anger around a little-noticed oil pipeline, Keystone XL, which has since become a national symbol of corporate greed and political arrogance for some and a national symbol of political fecklessness for others. McKibben, back at Middlebury that year to teach a course on “Social Movements, Theory and Practice” in the spring semester, noticed an article by James Hansen, the NASA scientist who in 1988 first testified to Congress about the greenhouse effect. Hansen’s article argued that because new technologies had tapped “unconventional oil,” especially those trapped in tar sands, we weren’t reaching “peak oil” and the inevitable follow-on transition to renewable sources of energy. The construction of the Keystone XL pipeline, which would deliver tar-sands extracted oil from Canada to heartland United States, would strike a blow to the rise of renewable energy.

McKibben reached a decision, described his book Oil and Honey, to “organize the first major civil disobedience action for the climate movement.” Shrinking personal carbon footprints and tweaking lifestyles wasn’t going to cut it: “It was time to stop changing lightbulbs and start changing systems.” He drew on the lessons of Martin Luther King, Jr. The environmental movement needed “the power King had tapped: the power of direct action and unearned suffering.” That is, “We’d need to go to jail.”22

A few months later, in August 2011, McKibben did just that. He and 80 others spent a weekend in D.C.’s Central Cell Block after plopping down outside the White House fence. McKibben had spent “all summer plotting to get us arrested.”23 To his surprise, it worked.

350.org’s anti-Keystone campaign shaped the divestment campaign that followed. Both campaigns depend on directly intimidating opponents with raw people power and anger. Both preach peaceful demonstration but seek to provoke reactions that allow them to pose as “oppressed” victims of oligarchic power. McKibben’s plotting to go to jail is echoed in divestment campaigners’ delight in directly clashing with campus administrators. When in April 2015, 19 Yale students holding a sit-in at the president’s office were removed by campus police, the local campaign, Fossil Free Yale, immediately publicized a press release proclaiming, “Yale would rather arrest its students than re-engage in the conversation.”24 It didn’t matter that that morning President Peter Salovey had sat down with his unplanned visitors and conversed.

Divestment taps into student anger and longing for a cause, but it also creates both that anger and that desire for a cause-focused community.

Like #NoKeystoneXL, divestment is a grassroots movement that bubbles into local boiling points, each of which is managed by a strategy and a network of organizers. Divestment taps into student anger and longing for a cause, but it also creates both that anger and that desire for a cause-focused community. National networks of power undergird the campaign. Organizational machinery creates a momentum that otherwise appears organic. Without 350.org and its astroturfing simulation of grass-roots inspiration, there would be no international divestment campaign.

Sowing Seeds of Divestment

There was a small divestment campaign before 350.org took it up. But without Bill McKibben’s prominence and 350.org’s funding and strategy, it never would have ignited an international movement.

This first fossil fuel divestment campaign developed in fall 2010, two years before McKibben took his math on tour. Twelve students hatched the idea at Swarthmore College, an elite liberal arts college near Philadelphia with a heritage of progressive Quaker activism. That campaign, described in more detail in chapter 2, began after George Lakey, a Quaker activist and visiting professor of peace and conflict studies, brought his students to West Virginia to witness mountaintop-removal coal mining. His class returned to campus determined to wage a symbolic solidarity battle against fossil fuel extraction, and hit upon the idea of divestment.

The campaign garnered some traction. In spring 2012, a year and a half after the group formed, Swarthmore Divestment taps into student anger and longing for a cause, but it also creates both that anger and that desire for a cause-focused community.

Mountain Justice collected close to 700 student signatures on a petition supporting divestment. But it did not spread far beyond the groves of the Philadelphia suburb until after McKibben’s Do the Math Tour catapulted the issue to prominence. Only after the issue caught on did Swarthmore develop into an important hub of training and organization. Since 2013, Swarthmore has hosted a national conference for divestment activists, founded the national Fossil Fuel Divestment Students Network, sent graduates into nearly every organization now working on divestment, and coordinated closely with national 350.org divestment campaigners. But McKibben’s push was vital.

Meanwhile, a handful of other organizations dabbled in coal divestment campaigns. In June 2011, the Wallace Global Fund, founded by former US vice president and progressive activist Henry Wallace, hosted a meeting at its Washington, D.C. headquarters to discuss a coal divestment campaign.25 That fall, the Sierra Club’s Student Coalition launched two pilot divestment campaigns as part of its Campuses Beyond Coal project. Campuses Beyond Coal, first launched in 2009 and eventually growing to sixty campus chapters, targeted colleges that generated electricity from coal power plants and demanded they switch to solar and wind sources. In fall 2011, two chapters at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign pioneered simultaneous coal divestment campaigns. They asked their universities to divest from the “filthy fifteen,” a list of coal burning utilities companies and coal mining corporations. Simultaneously students working closely with Swarthmore activists began Earlham REInvestment, a coal divestment campaign at Earlham College in Indiana.26

In 2012, As You Sow, one of the groups present for the Wallace Global Fund’s divestment summit, published a “Coal Divestment Toolkit” that listed the “filthy fifteen” companies and asked students to help turn coal into a “pariah industry” that had lost its “social license to operate.”27 The toolkit and accompanying campaign infrastructure were funded by the Wallace Global Fund and the Educational Foundation of America. They were developed in partnership with ten other organizations: the California Student Sustainability Coalition, a network of student activists across California universities; Coal Swarm, an online directory of campaigns against coal; Energy Action Coalition, an emerging group of activists and organizations trying to speed the transition to wind and solar sources of energy; the Green Corps, a one-year field school for environmental activists; IB5K, a digital media group founded by the organizers of President Obama’s wildly successful online outreach during his 2008 presidential campaign; the Responsible Endowments Coalition, an investments advocacy group that advised the Swarthmore campaign; the Sierra Club and Sierra Student Coalition; the Sustainable Endowments Institute, a spin-off of Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, Inc. that advocates for climate-focused investments; and The Engage Network, a campaign management consultant.

The coalition assembled at the Wallace Global Fund introduced students to the idea of fossil fuel divestment as a tool to provoke climate policy, but it was Bill McKibben who gave the idea popular credibility. Wallace Global Fund managed to start six coal divestment campaigns early in fall 2012, just after Bill McKibben released his Rolling Stone article and just before he traversed the nation on the “Do the Math” tour. By the end of the fall semester, there were 50.

Activists at the Sierra Club pilot campaigns felt the rush of energy McKibben brought. Jasmine Ruddy, who joined UNC Beyond Coal her freshman year, just as the campaign moved away from protesting coal power plants and directly into divestment, said McKibben gave the divestment campaign cachet. When she first started training students, they had never heard of divestment and didn’t know or care much about the endowment. “People just looked at us like we were nuts—like this was just about finances, and had nothing to do with direct action and organizing students. We were trying to explain that it could do both.” It was lonely work: “I felt like we were walking in the dark with just us, Illinois, and Swarthmore.” Ruddy credits McKibben with doing a “fantastic job conveying to people that divestment is the most important thing that students can be doing to act on climate change.” The UNC campaign received direct help from 350.org, and the Sierra Club remained the group’s main funder and adviser, but Ruddy attributes the campaign’s surging popularity to 350.org.

Two colleges, in some ways, beat McKibben to the idea of fossil fuel divestment. Humboldt College quietly excluded fossil fuel investments for years. In 2014, more than a decade since it last held fossil fuel stocks, the college announced its “divestment” by “continuing” to screen out certain investments, including fossil fuels.28 Meanwhile Hampshire College established an “affirmative” investment policy in January 2012 that required all investments to meet specific standards of sustainability and social improvement.29 Under this policy the college sold its fossil fuel stocks seven months before McKibben called on universities to “do the math.”

Disruption

Within a few months of “Do the Math,” divestment was well underway. In December 2012, the City of Seattle became the first city to withdraw its investments from fossil fuels. In February 2013, Sterling College in Vermont divested,30 then Maine’s College of the Atlantic in March.31 By the end of May, Green Mountain College in Vermont32 and San Francisco State University Foundation had joined,33 bringing the total number of college divestments to six.

Growing in confidence, the campaign became more aggressive. In February, Swarthmore students arranged for a “convergence” to train and rally student divestment activists. More than 200 students from 75 campuses flocked to the college. “PowerUp! Divest Fossil Fuels” met to discuss three goals: developing campaign tools for students to share; creating a communications network for students across the country (later that year, students forged the Fossil Fuel Divestment Students Network); and scaling up the movement while making it more “inclusive.”34

Lilian Molina, a “mestiza environmental justice advocate,” gave a plenary session talk about the environmental justice movement’s roots. The environmental and civil rights movements first intersected in 1982, she said, in Warren County, North Carolina. There, in the town Shocco with a 75 percent African American population, the state of North Carolina had arranged to build a landfill for soil contaminated with Polychlorinated Biphenyls (a chemical banned from industrial use in 1979). The ensuing protests fused the non-violent techniques and concerns of the civil rights movements to environmental ends—and although they did not prevent the creation of the landfill, they ultimately succeeded in forcing its removal.

Molina urged students to work in “solidarity” with the “frontlines communities,” but to note their own positions of “privilege,” and to be careful to respect local communities. One of the first principles of the Bali Principles of Climate Justice, which Swarthmore Mountain Justice adheres to, is to affirm “the rights of indigenous peoples and affected communities to represent and speak for themselves.”35 Evidently a divestment campaign planned by students at an elite institution trying to express solidarity for the West Virginians they had met did not constitute “speaking” on behalf of them.

Further east, in April, 11 students at the Rhode Island School of Design plotted a surprise sit-in at the school’s administrative building. Divest RISD had collected signatures from 1,000 students (half the student body) and gotten a unanimous vote from the faculty senate on a resolution endorsing divestment, but the board had stalled. Sensing a need to “do something drastic,” organizer Emma Beede scheduled April 29th for campus rallies.36 While activists had hung banners from every dormitory and dropped a hundredfoot-long sign, core members of the team slipped inside from the quad and announced that they were occupying the president’s office and would not leave until the college agreed to divest. One day later they vacated, pacified with an invitation to give a formal presentation to the board. (In May, the board created a focus group to study divestment, and two years later, in June 2015, the school announced its divestment from direct holdings in coal companies.37)

Swarthmore’s unusually belligerent activists sparked one of the divestment movement’s most notorious episodes. At the May 2013 board meeting, opened for the first time to all members of campus, a mob of Mountain Justice activists flooded the room and seized microphones from board members. For an hour and a half students lectured the board on the cycles of oppression that haunted them at college, including the board’s failure to divest. When one student opposed to divestment stood to ask the meeting to return to order, the activists clapped in unison to drown her out and asked her to leave. The meeting moderator, the dean of students Liz Braun, and president Rebecca Chopp all declined to intervene.

#RejectionDenied

A series of divestment rejections checked the movement in 2013. Swarthmore officially rejected divestment in September 2013, citing its impotence to “change the behavior of fossil fuel companies, or galvanize public officials to do something about climate change.”38 Pomona College declined divesting a few weeks later.39 Rejections from Brown University40 and Harvard followed in October. Harvard President Drew Faust avowed that “climate change represents one of the world’s most consequential challenges” but argued that divestment did nothing to stop climate change and would only embroil the university in partisan politicking. In an oft-quoted passage, she explained,

We should, moreover, be very wary of steps intended to instrumentalize our endowment in ways that would appear to position the University as a political actor rather than an academic institution. Conceiving of the endowment not as an economic resource, but as a tool to inject the University into the political process or as a lever to exert economic pressure for social purposes, can entail serious risks to the independence of the academic enterprise. The endowment is a resource, not an instrument to impel social or political change.41

Instead, she said, Harvard would hire its “first-ever” vice president for sustainable investing, who would try to engage in shareholder advocacy.

“Conceiving of the endowment not as an economic resource, but as a tool to inject the University into the political process or as a lever to exert economic pressure for social purposes, can entail serious risks to the independence of the academic enterprise. The endowment is a resource, not an instrument to impel social or political change.” - Drew Faust, president, Harvard University

In December, the University of Vermont spurned divesting. A subcommittee of board members feared damaging the endowment’s performance.42 Barry Mills, president of Bowdoin College, had already declined to divest in December 2012, tantalizing students as he did so. “I would never say never,” he said.43 Vassar College, Cornell University,44 Colorado College,45 Bryn Mawr College,46 Middlebury College,47 the City University of New York,48 and Haverford College49 also said no to divestment.

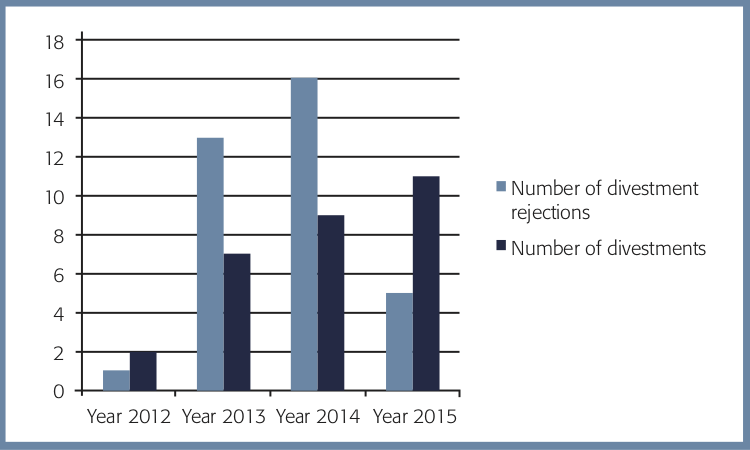

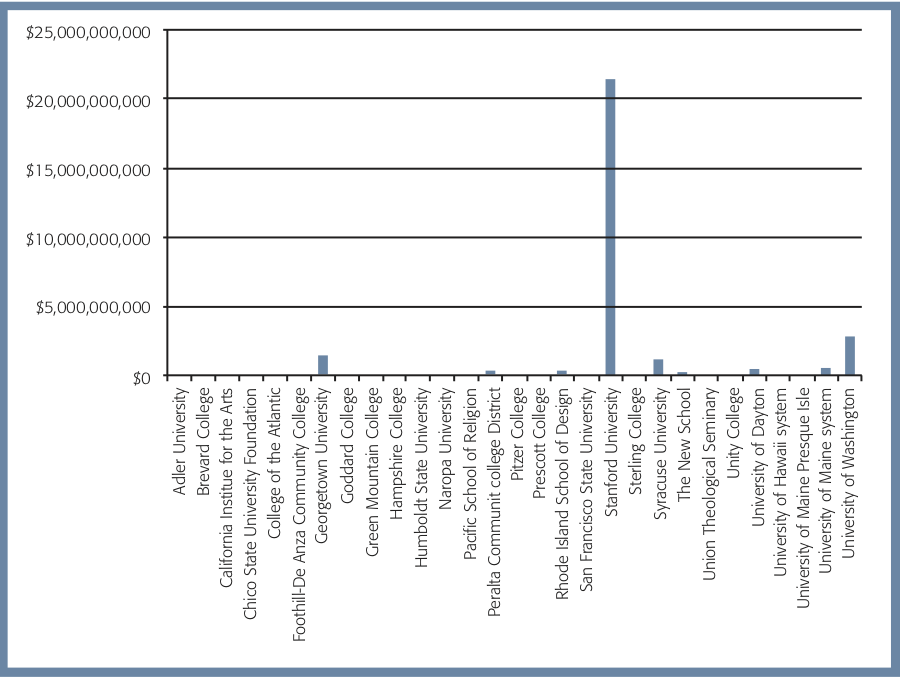

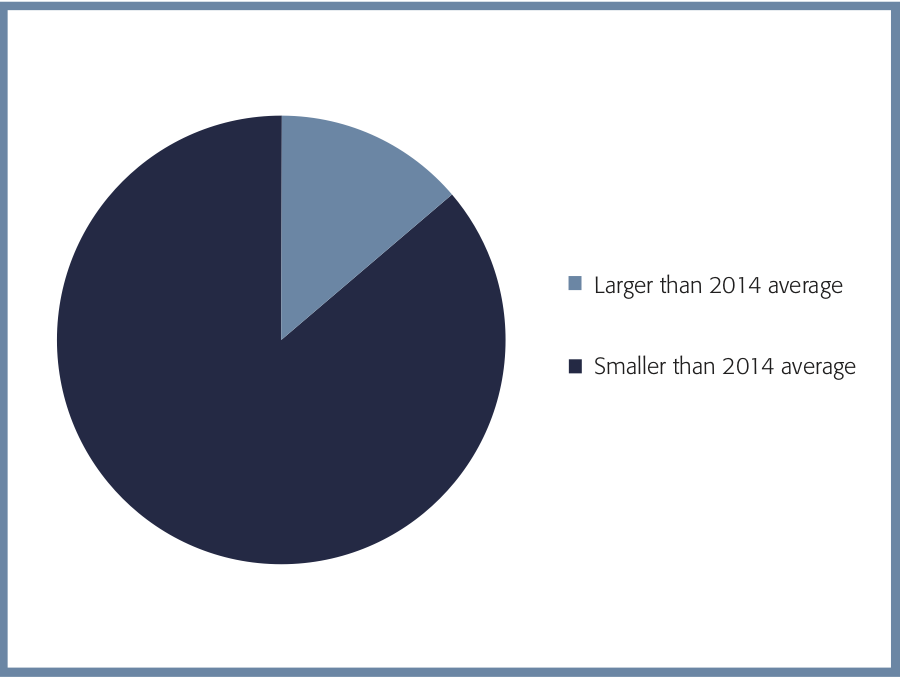

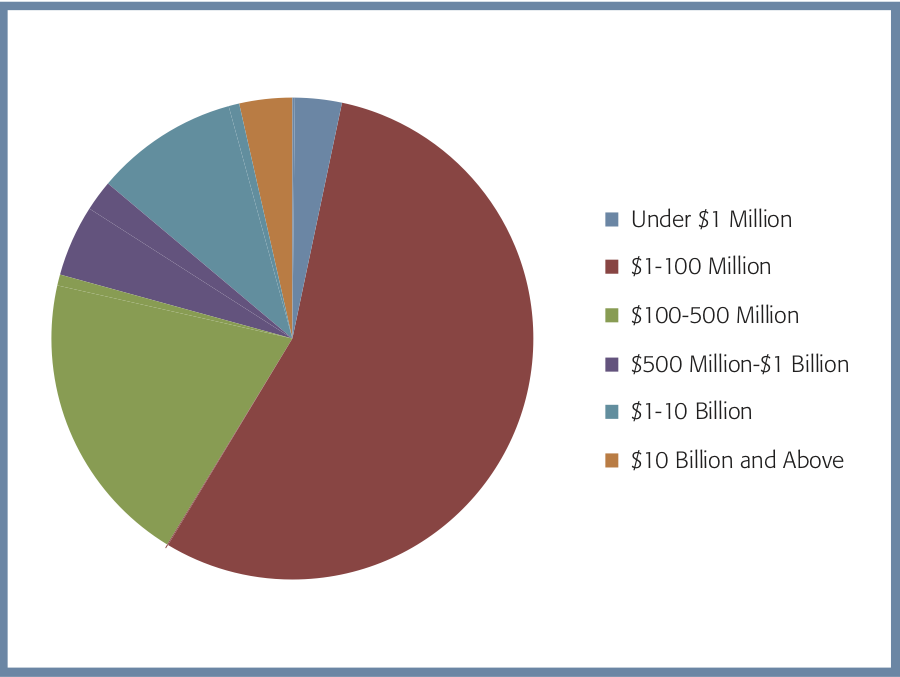

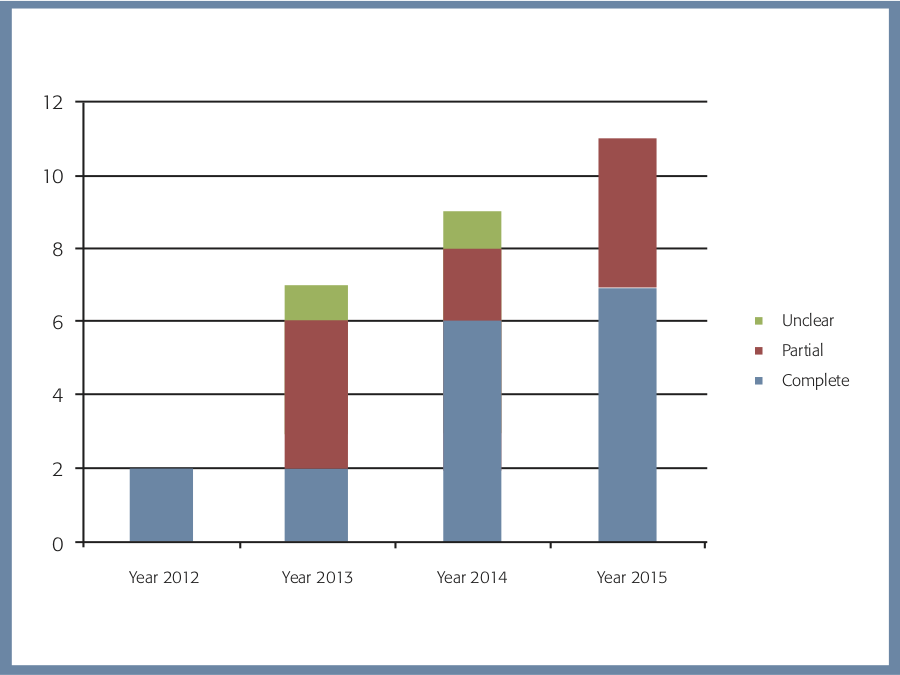

By the end of 2013, rejections outpaced collegiate divestments by a ratio of 3 to 2. The score stood at divestments, 9; rejections, 14. In 2013 alone, 13 colleges and universities declined to divest, almost double the 7 that did.

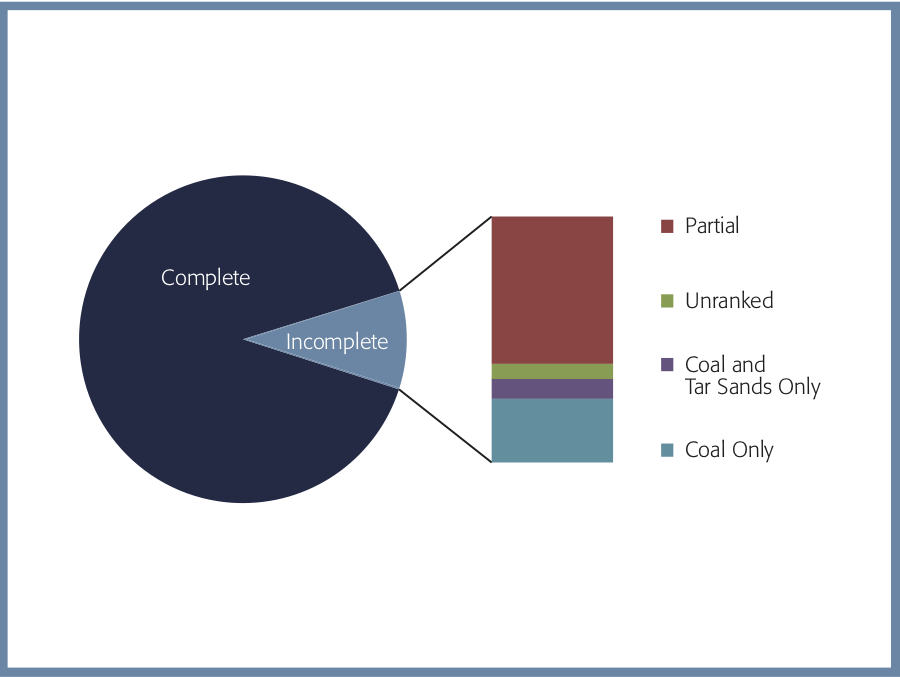

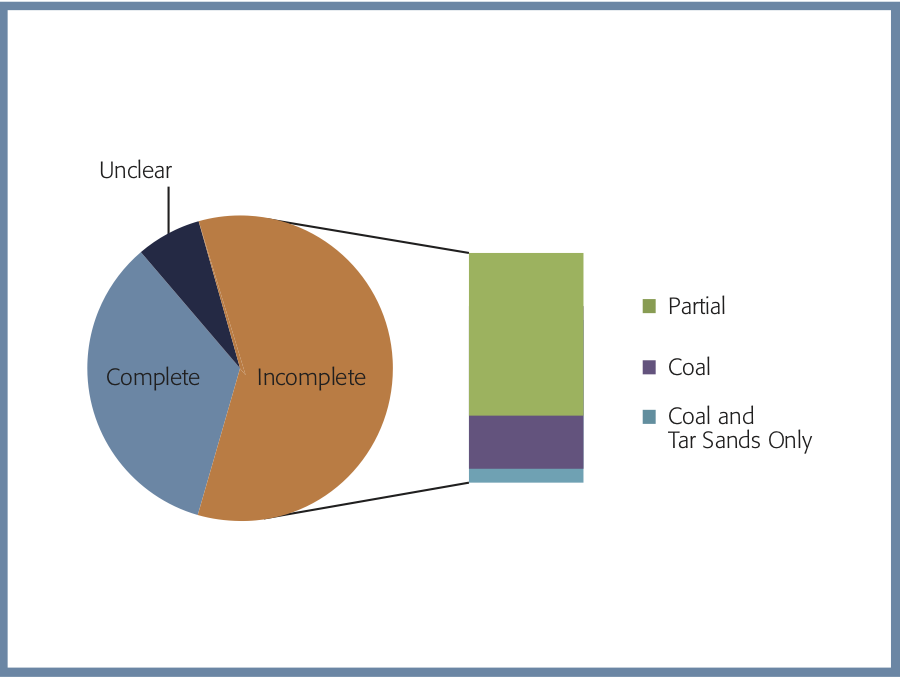

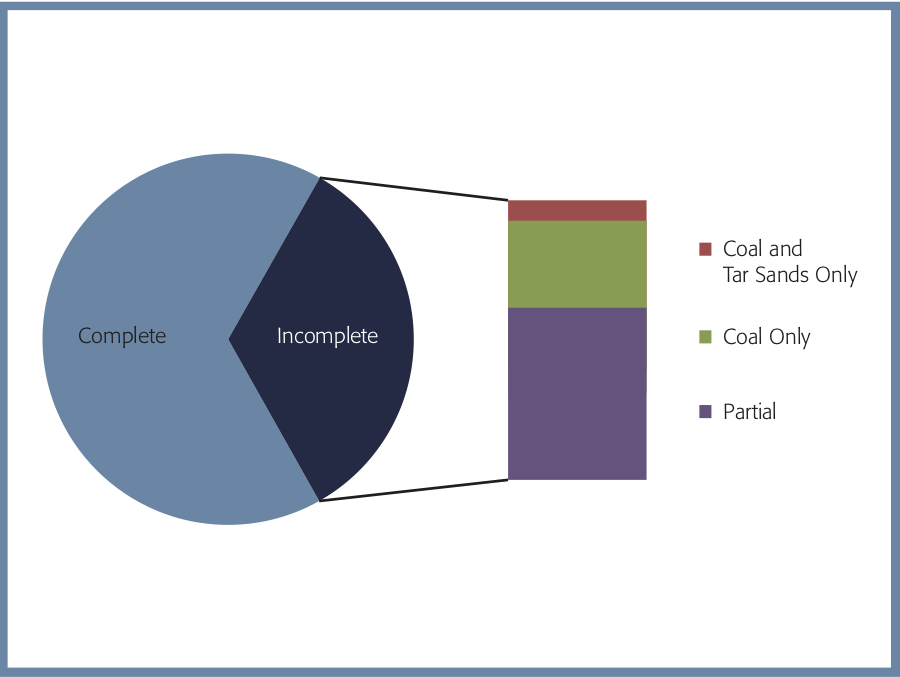

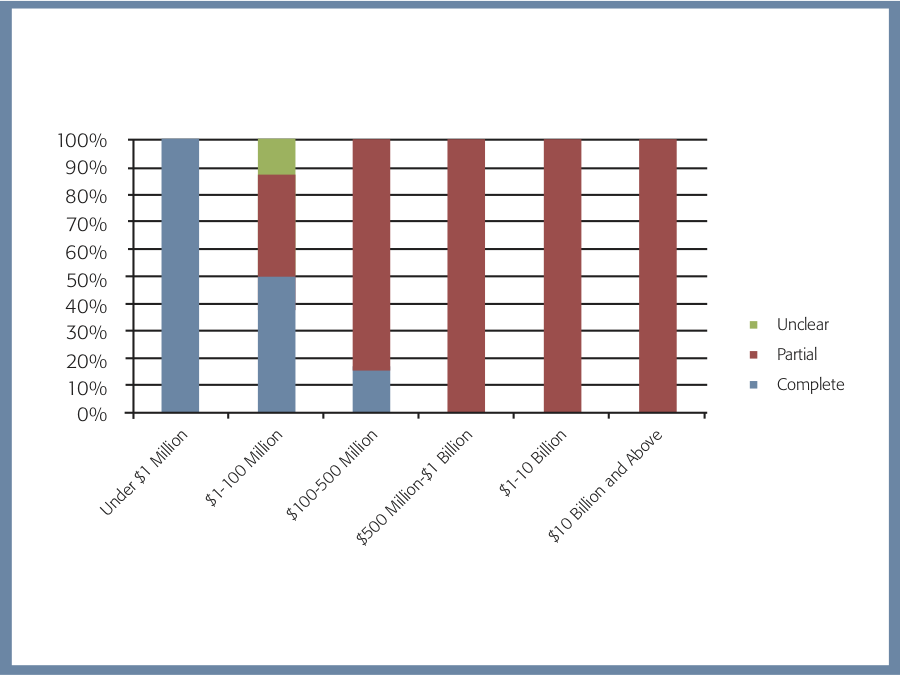

Figure 1 Number of Collegiate Divestments and Rejections by Year.

Rejections came from wealthy, respected institutions. Divestment victories, when they came, often came from small, little known colleges. On October 23, Foothill-De Anza Community College Foundation in California divested from direct holdings in fossil fuels and ordered investment managers to “minimize investments in commingled assets that include fossil fuel companies.”50 Eight days later, Naropa University, a Buddhist institution in Colorado, froze its fossil fuel investments and pledged to divest fully within five years.51 In December, Peralta Community College District in California pledged the same.52

In response, 350.org launched in December a strategy named with a hashtag: “#RejectionDenied.”53 Though presidents and trustees had announced they would not support divestment, no would not be allowed to mean no. “Their response… must not be mistaken for an answer,” 350.org divestment organizer Katie McChesney urged. “No is just a sign to escalate our tactics. No is just the motivator we need to build our power until there’s no option but yes.”54

To make the “power structures” (who cared more about “preserving pride and egos,” McChesney said) understand that students would not take “no” for an answer, students must pledge to “escalate” their campaigns. Only increased people power and pressure would make the board understand that “People who meet three times a year to talk about finances do not make up our institutions. Our alums, our faculty and staff, and our students are what make our schools great.”

Ten “NEST” (national escalation strategy team) campaigns signed McChesney’s pledge: Harvard, Cornell, Swarthmore, Pomona, Bryn Mawr, Middlebury, Boston College, Vassar College, Brown University, and Roosevelt University. Another 37 signed on in “solidarity,” pledging to escalate even if their proposal hadn’t been rejected.

“Escalation” on most campuses meant a decided shift away from negotiating with administrators and toward an all-out battle. A 350.org guidebook to divestment, released in May 2014, showed “escalation” as step 6 (the final one) in a series of campaign stages.55 Earlier stages were friendlier and less confrontational. After building a team of activists (step 1), divestment organizers were to make friends with professors and administrators, and see if any trustees were sympathetic. They should hold petitions, debates, film screenings, and other “educational” events, mixed in with a few “creative actions” that “make divestment the cool thing happening on campus.”

Only at step 4, “turning up the heat,” should they begin raising a ruckus, starting with a “creative demonstration outside the administration building” and a couple of op-eds or letters from alumni. Step 5, “pressuring the board of trustees,” included hosting “big demonstrations during the trustee meetings.” Escalation, the last-ditch effort to use only after “trustees turn you down,” was “a serious decision, as well as very exciting.” By those standards, Swarthmore’s seizing of a board meeting and Rhode Island School of Design’s sit-in were premature; neither college had rejected divestment yet. 350.org left “escalation” undefined, but gave several examples: convincing seniors to withhold donations until the college divests, or perhaps occupying the administration building. Essentially “escalation” meant being stubborn and discarding the veneer of civility.

In December 2013, one day before McChesney officially announced the escalation strategy, 150 students from Boston College, Boston University, Harvard, Tufts, Brandeis, MIT, Northeastern University, Wellesley, the Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering, and Lesley University (five of which signed the NEST pledge) marched through Boston and dropped banners from bridges declaring their commitment to reject any rejections.56

At the end of April 2014 an “escalated” Harvard campaign blockaded the main entrance to Massachusetts Hall, where president Faust’s offices were. They wanted another meeting to discuss divestment. Staff members merely detoured to side entrances, but the next morning, May 1st, additional protesters began blocking all entrances to the building and preventing staff from entering their offices. These new protestors included prominent author and divestment veteran Bob Massie and the university’s Quaker chaplain, John Bach. Campus police asked the blockaders to step aside. A junior, Brett Roche, refused to leave and clung to a doorknob. After repeated warnings, campus police arrested him.57

Post-Escalation

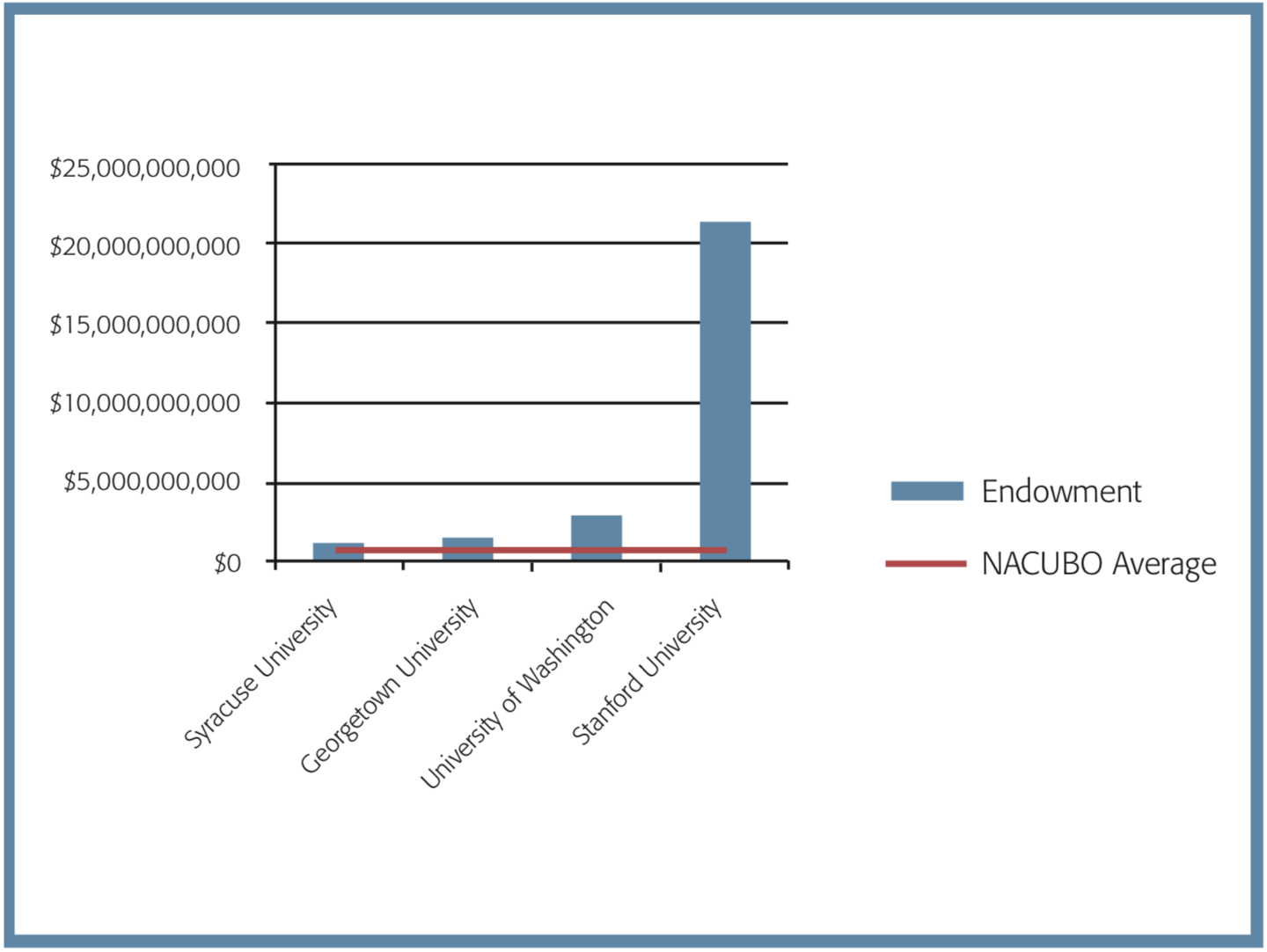

Escalation did correlate with some high-profile victories. In the spring of 2014, shortly after San Francisco State University held a second divestment convergence for activists,58 the nationally recognized California liberal arts college Pitzer agreed to divest its $134 million endowment from all direct holdings in fossil fuel companies.59 The college also pledged to reduce its carbon footprint 25 percent below current levels by the end of 2016; establish a Campus Sustainability Taskforce; and create the Pitzer Sustainability Fund within the endowment to invest in “environmentally responsible investments.” A month later Stanford divested its endowment—$21 billion—from direct holdings in coal.60 Along the way tiny Prescott College in Arizona divested.61

Here, as usual, correlation didn’t signal causation. Pitzer and Stanford both had trustees negotiating from within. At Pitzer, investment chairman Donald Gould, a hedge fund manager who was persuaded by the Carbon Tracker math, persuaded the rest of the board to come around to divestment. Another board member, the actor Robert Redford, backed him up. Stanford had board member Tom Steyer, the billionaire hedge fund investor who in 2012 arranged for a one-on-one mountain hike with Bill McKibben that left him persuaded to endorse the environmentalist’s campaign. Steyer arranged to divest his own wealth and founded Next Generation, a $4 million nonprofit aimed at promoting “clean” energy.62 Next Generation’s sister political action committee is Next Gen, which spent $74 million63 ($67 million of which Steyer contributed64) in the 2014 elections.

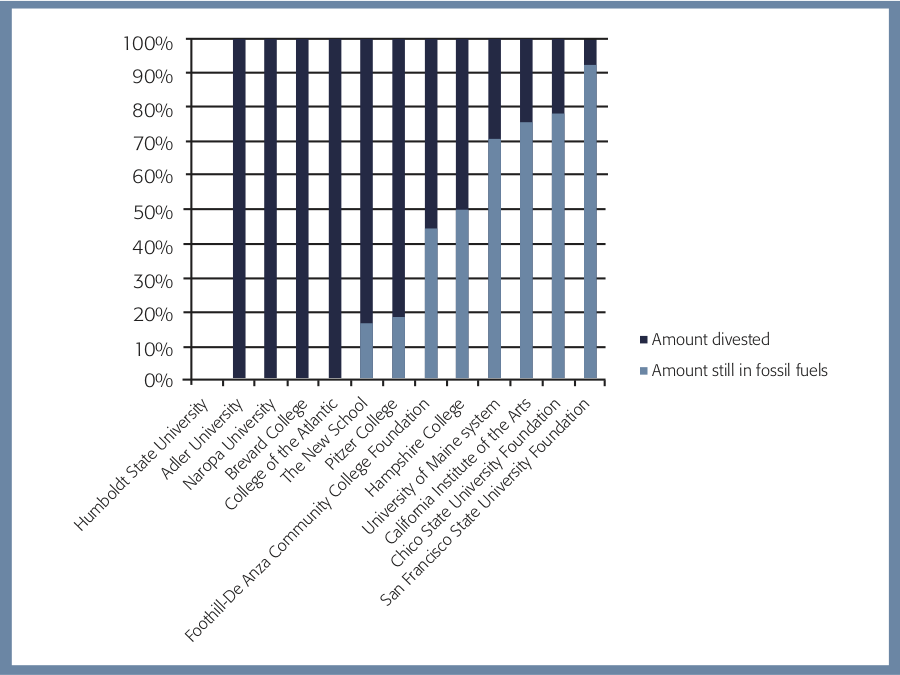

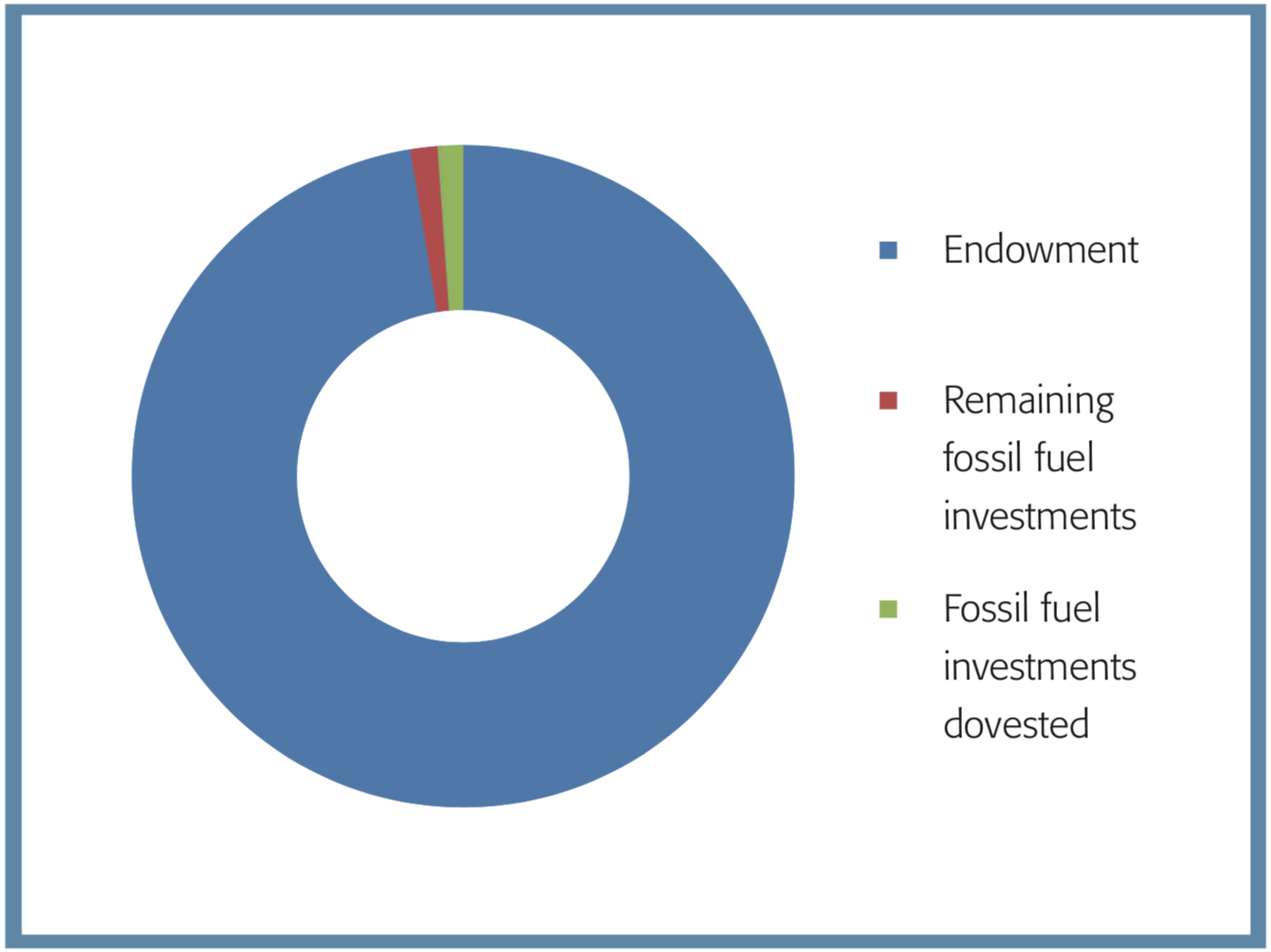

As demands grew louder, openings for compromises emerged. Stanford divested from its direct investment in coal, leaving oil and gas untouched, and keeping any commingled funds (some of which included fossil fuels) in place. There were also opportunities for vanity PR. California’s Humboldt State University, the one that hasn’t held direct investments in fossil fuel companies for more than a decade, announced a stricter divestment meant to shrink remaining indirect investments in fossil fuels, along with casinos, tobacco, utilities, aerospace, defense, and alcohol.65

During summer 2014, the Fossil Fuel Divestment Student Network formed the “Escalation Core” team to orchestrate more aggressive actions. They popularized a “#BankOnUs” pledge to continue organizing and protesting despite administrations’ rejection of divestment and the students’ own graduations.66 As the movement’s visibility grew, administrators started their own campaigns. In June 2014, Union Theological Seminary announced its divestment.67 Students there had never said a word about divestment, but board member Michael Johnston, a long-time acquaintance of McKibben who had served with him on the board of the Schumann Media Center, a major funder of McKibben’s work, convinced his fellow trustees that it was a good idea.68

Two weeks later, the University of Dayton, a Jesuit university in Ohio, divested unasked by the student body. President Dan Curran championed the issue himself.69

Contrived Confrontation

Essentially the entirety of the divestment campaign for the past two years has been one collective pledge to “escalate” into increasingly shrill demands. The movement relies on scare tactics, threats of ruckus, and contrived confrontation. Board members bend over backwards to listen to student demands, then get labeled “oppressors” and “climate change deniers.” They aren’t by any reasonable definition, but that’s part of the escalation. Anything besides full agreement counts as immorality.

To date, the fossil free divestment movement has been peaceful. …But the environmental movement has a history of vandalism and violence.

Pledges to escalate leave students in a bit of bind, however. What do you do after you’ve escalated and still been declined? Escalate the escalation? There are only so many ways to scream before you grow hoarse and destroy your own credibility. To date the fossil free divestment movement has been peaceful; the most aggressive actions have involved sit-ins and blockades. Most activists have taken pledges to remain nonviolent. But the environmental movement has a history of vandalism and violence. Earth First, organized in 1979 with the motto “No compromise in the defense of Mother Earth!” has vandalized property in the name of protecting the Mother. Others, such as the Deep Green Resistance movement, ask their members to take pledges of nonviolence with the expectation that such pledges hold only during “phase 1” of the “resistance,” during which the Resistance develops “a solid foundation—an organization and community that can be resilient and adaptive.”70 After that comes “Phase II: Sabotage and Asymmetric Action.” During Phase II, activists “push for acceptance and normalization of more militant and radical tactics where appropriate” and “vocally support sabotage when it occurs.”71 “Phase III: Systems Disruption” involves “underground networks organized in a hierarchical or paramilitary fashion.” The last phase, “Decisive Dismantling of Infrastructure,” requires an all-out war on capitalism, and the “collapse” of “civilization.” The divestment movement’s claims about the imperative urgency of its program, combined with the intolerance it has already exhibited at places such as Swarthmore, make it legitimate to wonder if divestment advocates will keep to non-violent tactics if the movement encounters sustained resistance.

Fall 2014 and spring 2015 were punctuated by campaigns fishing about for new ways to turn divestment into a wedge issue. Swarthmore students set the goal of “polarizing” their campus.72 “#WhoseSide”became the Twitterspeak rallying cry for the spring semester.

People’s Climate March

Three events gave students an excuse to escalate into confrontation: the People’s Climate March in September 2014, Global Divestment Day in February 2015, and the so-called “Divestment Spring”/”Escalation Season” in March and April 2015.

The New York Environmental Justice Alliance organized the People’s Climate March in the streets of New York City on September 21, 2014, to signal popular support for climate regulations to be debated in Paris at the end of 2015. The organizers estimated that 50,000 students came, while 350.org believed that there were 400,000 marchers in all. (The number has been disputed. The New York Times reported 311,000;73 Wall Street Journal “hundreds of thousands”;74 and the Associated Press “tens of thousands.”75 350.org’s Jamie Henn said his organization had guessed based on the crowd density shown in photographs of the street marchers, inflated the figure by 10 percent to include people on sidewalks, and then added another 90,000 to count those who left the march midway and drifted into Central Park.76)

One day before the march, on Saturday, September 20, some two or three hundred divestment activists met for another “convergence” at the Martin Luther King, Jr. High School on New York City’s Upper West Side. Leaders of the Divestment Student Network circulated the escalation pledge and introduced an alumni pledge, meant to prevent students from “graduating out” of the movement. Their mottos for the year were “dig deep, link up, and take action.” There would also be a series of seven training sessions scattered around the country, training students to escalate toward victory. Students from “UnKoch My Campus” leafleted students with pamphlets decrying the influence of oil money in higher education. Varshini Prakash, a paid Go Fossil Free Fellow who organized her UMass-Amherst campus, declared “This is about power! This is about our power!” and cast divestment as a tool against oppressive authority structures that excluded young people.

A second action, illegal and never officially sanctioned by the march organizers, brought hordes of students streaming into the financial district. Much like its predecessor Occupy Wall Street, Flood Wall Street demanded radical economic changes, wealth redistribution, greater use of renewable energy, and more divestments. Naomi Klein called it “a critical new phase of the climate movement, one built on peaceful, focused and fierce resistance.”77 Divestment activists concurred. The convergence on Saturday was abuzz with talk of joining Flood Wall Street. Marching with thousands down Broadway was fine, and historic, but running through Wall Street on Monday, with the tantalizing threat of arrest very much real, was appealing. On Monday, protesters sat in the streets for eight hours. More than 100, including some students, were arrested.78

One day after the People’s Climate March, the same day that students flooded Wall Street, Rockefeller Brothers Fund, heir to John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil fortune, announced a partial divestment. The fund would reduce its exposure to coal and tar sands to 1 percent of the portfolio by the end of the year. Trustees would perform a “comprehensive analysis” of oil and natural gas investments and “determine an appropriate strategy for further divestment over the next few years.”79

Two months later, in November, as other campuses diligently trained their new recruits, and as the Divestment Student Network traversed the nation holding training sessions, Divest Harvard kicked off the second part of its escalation campaign. Seven students filed a lawsuit against Harvard for failing to divest from fossil fuels. The suit, Harvard Climate Justice Coalition v. Harvard, listed as its plaintiffs Alice M. Cherry, Benjamin A. Franta, Sidni M. Frederick, Joseph E. Hamilton, Olivia M. Kivel, Talia K. Rothstein, Kelsey C. Skaggs, plus “future generations.” It alleged that by investing in fossil fuel companies whose products contribute to climate change, the university was guilty of “mismanagement of charitable funds” and “intentional investment in abnormally dangerous activities.” It also argued that Harvard’s investments embroiled it in funding climate change denial, had “a chilling effect on academic freedom,” and undermined both the graduates’ quality of education and their job prospects.80 In March 2015, a judge dismissed the case.81

Also in November, students calling themselves “THE General Body” at Syracuse University occupied the president’s office demanding a litany of reforms, including divestment from fossil fuels, greater racial diversity, more support for victims of sexual assault, and satisfaction of other grievances.82 The same month, Canada’s first Fossil Free Convergence brought together 80 student divestment activists for the country’s first divestment convergence.83

Global Divestment Day

“Break Up with Fossil Fuels” is a well-worn divestment demand. On Valentine’s Day 2014, Divest Harvard delivered 130 paper hearts to President Faust, asking her to “Be my Valentine this year, not Exxon’s,” and exclaiming “You belong with clean energy!”84 The earliest oil-break-up sketch dates to 2013, when students at the University of Vermont85 and at McGill University86 made a similar request.

Global Divestment Day, scheduled for February 13-14, 2015 by 350.org, asked the whole world to “break up” with fossil fuels. 350.org counts 450 events in 60 countries.87 These included an “oil spill die-in” at Rutgers University,88 a Mardi Gras float at Tulane University reading “Keep New Orleans A-float,”89 and a ceremony at the University of California–Santa Cruz marking the “unholy matrimony” of the university and its “long time beau, Fossil Fuel Industry.”90 Presumably the groom looked slick.

Harvard activists held a sit-in of the president’s office, armed with snacks, diapers, and cell phones to sustain them until President Faust agreed to meet inside and hear their demands.91 Northwestern University students, perhaps mimicking Harvard’s November legal ploy, staged a mock lawsuit, People vs. the Climate, to put coal on trial for crimes against humanity.92

As the fracking boom sent oil prices plummeting, 350.org urged students to play the oil glut to their advantage. “Kick it while it’s down” was the internal slogan. As part of a web workshop video training series in the weeks leading up to Global Divestment Day, Naomi Klein, author of the bestseller This Changes Everything: Capitalism Vs. the Climate and a board member of 350.org, urged activists, “it can be a really, really good time to get off fossil fuels.”93 Abandoning the now-defunct “peak oil” argument, Klein held that the capitalist system was killing itself, as competition forced companies to pull back on production and leave their reserves in the ground.

Divestment Spring

Eleven colleges and universities saw sit-ins for divestment during spring 2015.They ranged from a one-hour sit-fest at Whitman College94 to a 32-day occupation at Swarthmore College.95 Fossil Free Yale paraded 48 people through President Peter Salovey’s office before settling in a hallway for a day.96 Bowdoin Climate Action lasted two days outside President Barry Mills’ office.97 Divest UMW arranged a rotating line-up of 150 students, alumni, and activists for 21 days at the University of Mary Washington.98 Wesleyan University’s Coalition for Divestment and Transparency,99 Fossil Free CU at the University of Colorado Boulder,100 Tufts Climate Action,101 Divest Tulane,102 and UC Berkeley’s Fossil Free UC103 also held sit-ins. Divest Harvard held a five-day “Harvard Heat Week,”104 with vigils; a Fight for $15 minimum wage rally; speeches by Bill McKibben, filmmaker Darren Aronofsky, former Senator Tim Wirth; and one more blockade of Massachusetts Hall, plus a sit-in at the alumni building.105 (See Appendix VI for a directory of all campus fossil fuel divestment sit-ins.)

The nod to the “Arab spring” is intentional. In the eyes of divestment activists, their cause is cut from the same cloth as the Middle Eastern push for democracy.

“Divestment spring” is what activists called the sit-ins.106 Other monikers include “sit-in season” and “escalation season.” The nod to the “Arab spring” is intentional. In activists’ eyes, their cause is cut from the same cloth as the Middle Eastern push for democracy. Both demand paying attention to the opinions of people who currently don’t have much say in decisions they would very much like to influence.

“President Mills has been allowed to act with unilateral conviction and disinterest (sic) in the opinions of the students and faculty around him,” Bowdoin Climate Action members charged after 28 students marched into Mills’ office on April 1.107 His refusal to “compromise” by divesting made “meaningful dialogue…impossible” and evinced a “dangerous and deeply cynical view of higher education” in which administrators, not students, made administrative decisions. They decided to sit in “in order to form a more transparent and accessible relationship with the college.”

Parents of Bowdoin students wrote an open letter endorsing the sit-in, noting that after Bowdoin Climate Action garnered the support of 1,000 students and 70 faculty members, “the Board has ignored any further conversation for more than 140 days.”108 Among the signatories was Harvard historian of science, Naomi Oreskes, author of the book Merchant of Doubt, which accuses fossil fuel companies of buying mercenary scientists to cast doubt on climate science and prevent political action. Oreskes’ daughter, Clara Belitz, was among the Bowdoin students sitting in President Mills’ office. Belitz wrote an op-ed for the student newspaper, the Bowdoin Orient, recounting how the board had “disappointed” her by rebuffing students with “a token meeting and continued silence.” She held that “Bowdoin students, faculty and alumni deserve better.”109 The nod to the “Arab spring” is intentional. In the eyes of divestment activists, their cause is cut from the same cloth as the Middle Eastern push for democracy.

At Yale, where 48 students were sitting in President Salovey’s office to convince him that “social justice” was a “new” reason to support divestment, 19 who refused to leave were escorted out by campus police and cited for trespassing. Fossil Free Yale reprimanded the administration: “Yale’s failure to engage in a conversation on climate justice shows just how unaccountable the true decision-makers are to the Yale community.”110 President Salovey had spoken with and listened to the protestors shortly after they arrived at his office on the morning of April 9, but “conversation” has now become social-justice code for “capitulation.” Hence Fossil Free Yale Project Manager Mitch Barrows could report with a straight face, “Yale would rather arrest its students than re-engage in the conversation.”111

None achieved divestments. Five of the 11 sit-ins resulted in meetings with trustees or college presidents. Some lingered long enough for the headline and photo-op but closed up right on schedule. Seven students at the University of California pitched tents on the quad the night before a board meeting but tore down the tent town immediately afterwards.112 Divest Tulane scheduled its three-day sit-in down to the fifteen minute mark and ended right on schedule.113

Two sit-ins prompted campus police action. Nineteen of Fossil Free Yale’s sitters-down refused to leave at the close of Woodbridge Hall at the end of the day and were ticketed for trespassing.114 Thirty at the University of Mary Washington, after a 21-day camp-out in George Washington Hall, were escorted out by campus police. Two students and a local resident were charged with trespassing but acquitted.115

Analysis

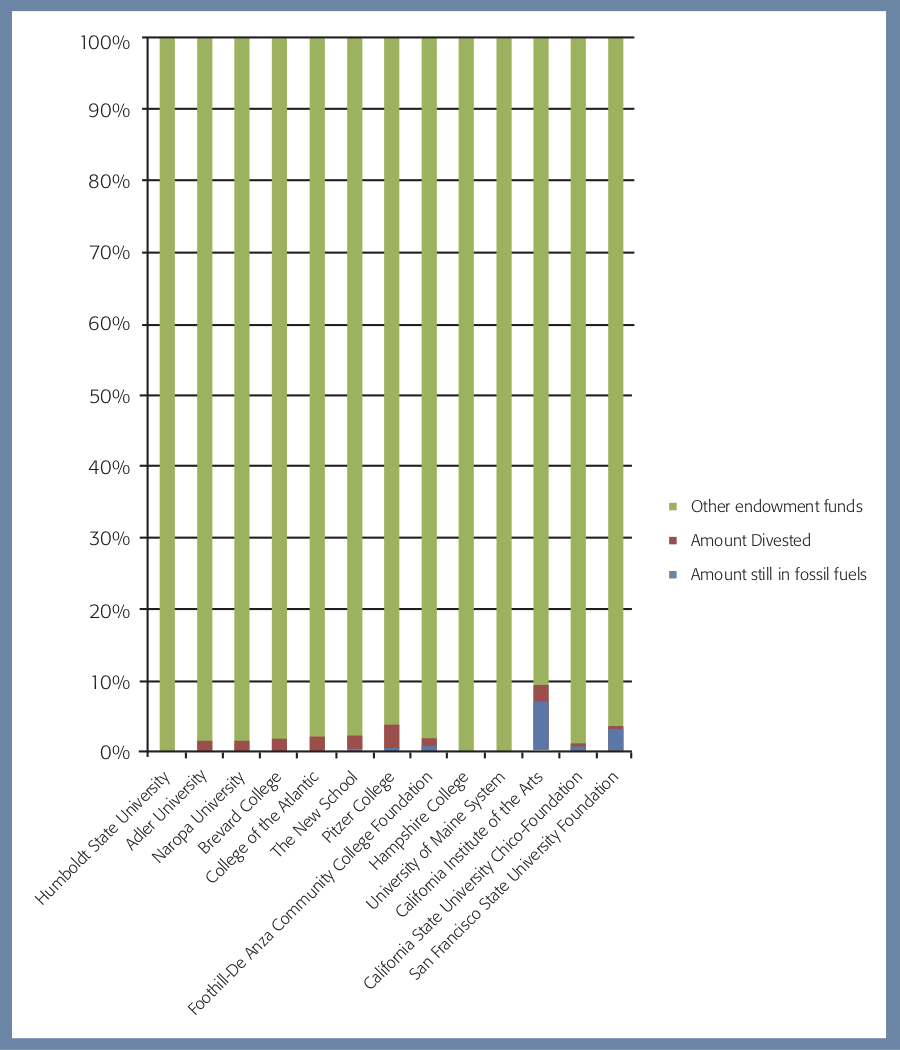

Did any of this work? The pace at which colleges have announced full or partial divestments from fossil fuels has increased since fall 2014. During the first four years of the divestment campaign, from Swarthmore Mountain Justice’s founding in October 2010 to the People’s Climate March in September 2014, 16 colleges and universities announced divestments. From September 2014 to June 2015, another 13 did.

In the five months from the People’s Climate March in September 2014 to Global Divestment Day in February 2015, six colleges and universities announced divestments. In December 2014, California State University-Chico announced plans to divest within four years, after a class taught by geography professor Mark Stemen focused on running a divestment campaign.116 Five days later, on December 15, California Institute of the Arts, which has no direct investments in fossil fuels, said it would withdraw 25 percent of its comingled investments in fossil fuels and seek to “eliminate exposure to the most carbon-intensive companies such as coal producers over the next five years.”117

On January 14, 2015, 209-student Goddard College in Vermont divested.118 On the 26th, the University of Maine system announced it would withdraw direct investments in coal companies.119 Four days later the University of Maine Presque-Isle, which manages its endowment separately from the rest of the University system, sent a press release announcing that it had secretly decided in 2013 to divest from fossil fuels and completed the process sometime in 2014.120

The biggest change in investment policy came from The New School in New York, which announced its divestment from fossil fuels, along with the creation of a climate change curriculum intended to form students into “climate citizens.”121

Since Global Divestment Day in February and the start of “Divestment Spring” sit-ins in March, another eight colleges and universities have divested. Brevard College, a Methodist institution in North Carolina,122 and “multidenominational” Pacific School of Religion in California123 both divested in February. In March, Syracuse University announced divesting its direct holdings in fossil fuels, before admitting it had none to divest.124 Then came the University of Washington (direct coal investments) in April,125 followed by Adler University in Illinois,126 and the University of Hawaii system127 in May. (Meanwhile, in April the Guardian announced its own plan to divest from fossil fuels.128) In the first week of June, both Rhode Island School of Design129 and Georgetown University130 announced their divestments from direct investments in coal companies.

None of the divesting colleges was among those whose students took the escalation pledge.

But none of the divesting colleges was among those whose students took the escalation pledge. None had lengthy embattled campaigns at their campuses. With the exception of Syracuse University, which agreed to divest its $0 direct holdings in fossil fuels five months after a student sit-in in November, none of the divesting campuses experienced a sit-in or other markedly “escalated” action. Perhaps the lesson is that escalation, if it does help, provides a free riders’ benefit to campus movements elsewhere that enjoy the campaign’s national visibility.

Moving Forward

Rejection provides the main momentum to the movement. McChesney, the 350.org organizer, called it “just the motivator we need.”131 At the convergence training just before the People’s Climate March, activist leaders called everyone who’d “gotten a no” on their divestment campaign to come forward in front of everybody, to be cheered and celebrated. Sara Blazevic, one of the Swarthmore leaders, wrote for 350.org in November 2014, almost a year since the “escalation” launch, that when she first joined Swarthmore Mountain Justice, she came back from West Virginia “wanting to organize tree sits on the main walkway of our campus and looking forward to attaching myself to a member of our Board of Managers via U-lock.” “I wanted our campaign to escalate,” she said, because “escalating meant bringing that urgency to our Board through highly confrontational tactics.”132 Just a few months later she was among those occupying the college finance office. Trustees have made divestment a hard fight, McKibben says, but that’s okay. The struggle makes the campaign all the more endearing:

The fight is just as important as the win in a lot of ways. Sometimes you can win almost too quickly in some of these battles. Instead, when you have to spend a few years fighting, then every freshman and faculty member and parishioner will come to know the story of why it’s so important.133

Divestment campaigns feed on anger, and anger is fostered by the frustrations of failure.

Divestment campaigns feed on anger, and anger is fostered by the frustrations of failure. Having a board of grey-haired wealthy trustees say no to young aspirations provides activists a convenient excuse to respond with indignation rather than introspection. The old are powerful and suppressing, the young powerless and suppressed, and so the moral imperative is to speak and act rather than to think. They need waste no time contemplating the possibility that divestment might be misguided.

The movement is gearing up for its third year of escalated campaigns. The Fossil Fuel Divestment Students Networks is raising money to sponsor 20 sit-ins in spring 2016. It is preparing a training schedule for the fall. 350.org is hiring Go Fossil Free Fellows, students paid to organize their campuses. The Responsible Endowments Coalition and Divestment Students Network are signing up alumni to join the protests. The activists are in it, they say, for the long haul.

Chapter 2: The Swarthmore Idea: The Cradle of Fossil Fuel Divestment

John Winthrop might be surprised at the updates to his “citty upon a hill.” It relocated, evidently, from the rocky coastline of Massachusetts to the wooded knolls of suburban Pennsylvania. Its residents, the Puritan immigrants who forsook England for the dangers and promises of the new world, have metamorphosed into the heirs of a rebellious Quaker heritage.

The new “citty” is Swarthmore College. The number-three ranked liberal arts college in the country, founded by Quakers in 1864, nestles into the hillsides of sedate Swarthmore Borough, which has 6,194 residents,134 counting the college’s 1,534 students.135 (The colony Winthrop led landed with about 700.) For the last five years, since the college birthed the first fossil fuel divestment campaign in 2010, the eyes of many have been upon it, much as the “eies” of seventeenth century Europe watched the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Kate Aronoff, a 2014 Swarthmore graduate, made the comparison in a March 2015 essay about Swarthmore’s divestment campaign in the left-leaning web magazine Common Dreams. “Like most elite institutions, Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania fashions itself as a sort of secular city upon a hill.”136 Aronoff noted the college’s founding by pacifists wanting out of the Civil War, and its contributing “generations of progressive organizers” who had worked to shape American society. These included suffragette Alice Paul (1905) and innumerable “civil rights and anti-war activists.”

Aronoff didn’t name them, but Paul, the woman behind the 19th Amendment and president of the National Woman’s Party for half a century, is not Swarthmore’s only famous activist alumni. Cathy Wilkerson, Swarthmore ’66, spent eleven months in prison for trying to blow up a military officers’ dance at Fort Dix, New Jersey, in 1970. She was a member of the Weather Underground and had participated in the Chicago “Days of Rage” actions, where for three days in October 1969 thousands of Weathermen and other members of the radical Students for a Democratic Society vandalized homes, smashed business windows, took hammers to parked cars, and charged into police officers. Two hundred eighty-seven Weathermen and SDS leaders were arrested. SDS spent $243,000 covering bail, including Wilkerson’s.137

Carl Wittman, who when he entered Swarthmore in 1960 was already a civil rights activist and spent summers canvassing the South, joined the national council of the SDS in 1963 as a college junior. He parted ways with SDS and the “New Left” for its failure to embrace homosexuality, and in 1969 wrote Refugees from Amerika: A Gay Manifesto. In the manifesto he accused “Amerika” of oppressing homosexuals in the “ghetto” of San Francisco. There, “capitalists make money off us, cops patrol us, government tolerates us as long as we shut up,” and “daily we work for and pay taxes to those who oppress us.”138 Wittman’s manifesto was published by The Red Butterfly of the Gay Liberation Front, the violent umbrella group that started the Stonewall Riots in 1969.

The activism brimming in the ‘60s and ‘70s at Swarthmore, which edged the 220-acre Crum Woods, reputedly brought Richard Nixon’s first vice president, Spiro Agnew, to dub the college “the Kremlin on the Crum.”139 Even if the attribution to Agnew is a folk legend, the phrase encapsulates the side of Swarthmore’s activist legacy that Aronoff does not emphasize: the radicalization that can lead students at a Quaker college to violence, and the intemperate rhetoric that takes America as simply hateful.

Is this the history Aronoff had in mind when praising Swarthmore’s heritage of rebellion? Aronoff and fellow fossil fuel divestment activists with her have taken pledges to engage only in nonviolent actions. They have no declared intention to wield hammers or pulverize glass. But Swarthmore’s mottled activist heritage “congealed,” Aronoff said, until the “college’s institutional identity” is now “as a place that prides itself as an incubator for social change.” Fossil fuel divestment was just the latest chick to hatch.

The fossil fuel divestment campaign at Swarthmore has been marked by intolerance, righteous indignation, and obstinacy.

Aronoff’s history is dubious: Quakers are pacifists, but Swarthmore was founded to provide an institution of higher education for Hicksite Friends, not as a refuge from the Civil War. Quakers traditionally look back to George Fox and William Penn, not John Winthrop and that Massachusetts “citty upon a hill” where they put Quakers in the stocks in one mood and hanged them in another. But Aronoff’s preference for the Boston of stocks and gallows is telling.

The fossil fuel divestment campaign at Swarthmore has been marked by intolerance, righteous indignation, and obstinacy. Students have denounced dissent as irrelevant and elitist, condemned administrators who repeatedly met with them as uncooperative, and shamed students into conformity.

As Swarthmore’s divestment campaign has been a model for the national one, a chronicle of its deeds illuminates the character of the larger movement. Activism campaigns are often treated by the press anecdotally, or with broad statistics. Both approaches obscure the social and cultural dynamics at play on the ground. A very small number of deeply engaged activists can project a movement much larger than it really is. To clarify the nature of the fossil fuel divestment campaign, we offer a history of the movement’s origins at Swarthmore, an investigation of the campaign and its tactics, and an analysis of the response from the college community.

A Model of 1980s Activism

Swarthmore’s fossil fuel divestment campaign traces its legacy to a previous generation’s apartheid divestment campaign. From the late 1970s until the late 1980s, students nationwide asked their colleges and universities to cancel investments in companies with assets, interests, or investments in apartheid South Africa. By 1988, 155 colleges and universities had withdrawn at least some investments from companies linked to apartheid.140

The Swarthmore Anti-Apartheid Committee organized in 1978. It circulated a petition that listed the injustices in South Africa and demanded Swarthmore divest, lest it sully its Quaker heritage. In two days, 640 students signed the petition. The board a month later adopted the “Sullivan Principles,” a popular outline of responsible investment guidelines drawn up in 1977 by a Baptist pastor, who recommended that all businesses adopt a race-neutral hiring policy but not that they cease activity in South Africa. Over the next seven years, Swarthmore divested from companies that failed to meet the Sullivan guidelines—$3 million in stocks moved. This did not satisfy divestment activists.

The next year, 1985-86, was a tug of war. In September 1985, students spent 20 days sleeping on the porch of Parrish Hall, the administrative building, leading up to a September 28 board meeting. They rotated in shifts and passed out red armbands to show support for divestment. Professors joined each evening to give talks. The night before the board met, 500 students converged from Swarthmore and the nearby colleges of Haverford and Bryn Mawr to sleep on the grass and ring the building with a candlelight vigil.

The board decided not to divest but appointed a committee to investigate other, more effective, ways to condemn apartheid. In response, on October 7, 35 students arranged a sit-in at Parrish Hall. On December 6, the board agreed to divest from additional companies that failed certain Sullivan Principles, but declined further divestment. In response 70 students marched into the middle of the meeting and sang. The board adjourned until the serenading intruders left.

From December 11-19, 50 students rotated through the president’s office for another sit-in. They wanted complete divestment from apartheid, and more recruitment of black students and professors to Swarthmore. The board agreed to the latter but again rejected divestment.

The first day in March 1986, students held a die-in on the lawn outside a board meeting. Six students and one professor attended the meeting to demand divestment. There, the board caved. It agreed to divest in stages. Three years later, in 1989, it adopted a schedule to divest $42.5 million, on the condition that “prudent” means were available. By 1990, the college fully divested.141 That year, the African National Congress was legalized, and Nelson Mandela was freed from prison. Britain became the first country to lift all restrictions on new investments in South Africa. Mandela won the presidential election in 1994, the first election in which citizens of all races were allowed to vote. All remaining international sanctions were lifted.

When Mandela visited California in 1990, he listed a litany of US allies: warehousemen from Union Local 10, who refused to unload a South African ship in 1984; the “workers, trades people, community activists and educators” who had held protests; the Bay Area Free South Africa Movement; and the University of California Faculty/Student Action for Divestment, which had successful led the university to divest.142

Swarthmore was slow to the apartheid divestment movement. When students formed their Anti-Apartheid Committee in 1978, banks had already begun five years previously to restrict loans to South Africa. In 1976, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger announced that the US would try political and economic levers against Apartheid; in 1977, the US supported a UN weapons embargo, though it then resisted a UN economic embargo on the nation. That year, Canada began phasing out commercial activity in South Africa.

By the time Swarthmore joined the movement, many colleges had already arranged to divest. Hampshire College, which in 1977 became the first American college to divest, beat Swarthmore to the mark by thirteen years.143 Swarthmore’s decision to divest itself of South African investments barely anticipated South Africa’s decision to divest itself of apartheid.

Divestment Central

The Swarthmore board of trustees has twice rejected divesting from fossil fuels. Activists have yet to lose hope. A quarter century ago the board rejected divesting from companies with ties to apartheid four times before finally agreeing.

Swarthmore remains a hub of divestment activism, and in many ways offers a microcosm of the larger divestment campaign.

Unlike their predecessors’ sluggish entrance into the apartheid divestment campaign, Swarthmore students led the way with the fossil fuel counterpart. The national campaign lifted off, of course, with McKibben’s endorsement in August 2012—almost two years after Swarthmore Mountain Justice formed—and 350.org rose to become the key sponsor of the divestment campaign. But Swarthmore remains a hub of divestment activism, and in many ways offers a microcosm of the larger divestment campaign.

When Bill McKibben first trotted the country doing his math, it was a Swarthmore sophomore, Sara Blazevic, who joined him onstage at his November 2012 Philadelphia stop. Blazevic acknowledged the importance of 350.org’s help: “Despite a wide base of support for our growing student power, it is abundantly clear that we alone cannot convince Swarthmore to divest. We need a mass movement to get this ball rolling.”144 Blazevic afterwards explained to the college’s student newspaper, the Swarthmore Daily Gazette, that “We made an alliance (with 350.org) because of their clout in the political and social movement world. Us being backed by 350 will give the message more force on campus.”145

McKibben returned the compliment. “Swarthmore’s in the lead,” he told the Gazette.146 “It’s one of the places in the country where the argument’s more advanced, going further down that road.” He added, “Swarthmore’s one of my favorite colleges in the country.”

The following three years have been marked by collaborations between Swarthmore Mountain Justice and divestment activists nationwide, including those with 350.org. In February 2013, the College hosted students from 70 colleges in what became the first of an annual “convergence” of divestment activists. During the summer of 2013, Swarthmore students helped found the national Fossil Fuel Divestment Student Network, which appointed itself responsible for training students and alumni nationwide. Swarthmore grads now work at nearly every organization active in the divestment movement (except, notably, 350.org). One set of six devoted alumni live together as the Maypop Collective for Climate and Environmental Justice. This donations-supported commune mentors activists and supports divestment and other campaigns that “fight the root causes of climate change to create a just and equitable future.”147 Swarthmore’s spring 2015 sit-in for divestment coincided with ten others nationwide, but lasted longer than its counterparts: 32 days. More than 200 students, alumni, staff, and faculty cycled through the building, taking turns keeping the hallways full.

350.org, for its part, checks in with Swarthmore Mountain Justice on a weekly basis. One of its divestment organizers, Katie McChesney, is based in Philadelphia and joins the students’ weekly planning meeting.

Mountain Justice