Introduction

It has long been assumed that the primary purpose of an undergraduate education in English literature is to impart a broad appreciation of the English and American literary traditions. It has been commonly—and we think correctly—believed that:

• exposure to a broad sampling of the greatest works in a variety of genres substantially improves the critical judgment of contemporary literary works;

• exposure to the best literature of many periods and styles improves everyday language use and enriches the creative resources of aspiring writers;

• close reading and interpretation of literary masterpieces strengthen the powers of analysis and imagination;

• study of the thoughts, stories, characters and situations brought to life in the greatest works broadens the mind, illuminates the past, affords perspective on the present, and provides encounters with intellectual and cultural diversity hard to achieve otherwise; and

• knowledge of the larger literary tradition provides an indispensable frame of historical reference for specialized literary studies.

This report asks whether English major programs at twenty-five of our nation’s leading colleges are, in fact, likely to impart an overall appreciation and understanding of the English and American literary traditions. A great deal of anecdotal evidence suggests that they may not. In this study we seek to move beyond anecdote by systematically analyzing their actual course content and programmatic requirements.

Description of the Study

The report analyzes English major requirements much as our earlier survey examined general education. In our 1996 study, The Dissolution of General Education: 1914–1993, we examined the structure, content, and rigor of undergraduate general education requirements, employing catalogue course descriptions to establish the expectations students were asked to meet. Except for the specialized focus, we do the same here.

There are advantages and disadvantages to catalogue studies. The great advantage is that they allow the efficient comparison of many different academic programs. Because catalogues establish an intellectual contract between student and institution, they must strive for some precision. Academic programs and individual faculty members also use catalogue descriptions to attract appropriately prepared students to both programs and courses, which provides another incentive for accuracy.

Course descriptions, however, also omit a good deal, and are sometimes outdated and deceptive. Often, they provide only outlines of the subjects covered and reveal little about the emphasis given to their component parts or particular readings assigned. At times descriptions are exceedingly terse, while at others they ramble on to astonishing lengths—doing more to confuse than to clarify academic content. Making sense of course descriptions thus involves grappling with ambiguities. Yet, if due caution is observed, much can be extracted. In this case we have used course descriptions to analyze the following program characteristics.

Structure

“Structure” refers to the degree to which, and the means by which, departments channel students through an orderly learning sequence, ascending from the basic to the advanced, and affording an overview of English and American literary traditions. Structure becomes manifest through required courses, which all majors must take, and “clusters,” which compel students to choose at least one course from a small, topically united group of offerings. For our purposes, a grouping qualified as a cluster if students were required to take at least a third of its courses. The greater the percentage of the major’s total credit requirement composed of mandated or clustered courses, the greater the major’s structure. Structure also expresses itself in the number and range of courses available as electives, and the number and scope of distribution requirements, in which students choose from a large number of related courses. A wide range of electives and capacious distribution requirements signify less structure.

Content

“Content” refers to the nature of the subjects a student must cover to complete a major. We evaluated content in the following ways:

1. We asked whether there was a required Shakespeare course or, failing that, at least one Shakespeare course grouped within a cluster.

2. We asked what percentage of a department’s courses was “foundational” rather than specialized. For us, a foundational course (a) surveyed the major works of an important literary period or movement, or (b) focused on a traditionally canonical author or small group (two to three) of such authors, or (c) examined a major literary genre.

For example, among the courses we counted as surveying major works, periods, and movements were English Literature of the Renaissance (Bowdoin, 1964–65); The Augustan Age (Smith, 1963–64); The Romantic Era (Barnard, 1997–98); and Nineteenth-Century American Literature (Hamilton, 1997–98). Examples of courses on major authors included Seminar: Henry James (Wellesley, 1963–64); Three Major Novelists: Fielding, Jane Austen, and Dickens (Williams, 1964–65); Swift and Pope (Oberlin, 1997–98); The Novels of Virginia Woolf (Trinity, 1997–98); and Seminar: George Eliot (Colby, 1997–98). Typical of courses on major genres were Epic and Romance (College of William and Mary, 1964–65); The Art of Poetry (Davidson, 1964–65); Prose Style (Mount Holyoke, 1964-65); The Short Story (Pomona, 1964–65); Reading Poetry (Amherst, 1997–98); Tragedy (Swarthmore, 1997–98); and The American Novel (Colgate, 1997– 98).

“Non-foundational” courses fell under several headings. Some dealt with such specialized subjects as Seminar: The Press as a Social Instrument (Grinnell, 1964–65) and The Harlem Renaissance and The Jazz Age (Swarthmore, 1997–98). Others emphasized authors not traditionally considered canonical. Many knit together disparate works on the basis of common themes like heroism, “otherness,” “spatiality,” travel, or “representations of self,” to mix traditional and contemporary examples. Quite a few were mainly interested in criticism or literary theory, or concentrated on non-literary matters like Victorian Culture or film. Finally, we considered a course non-foundational when its subject matter was largely composed of literature written within fifty years of the offering date.

Our unwillingness to classify a course as foundational should not necessarily be considered a negative judgment. Many non-foundational courses make fine undergraduate electives, and many foundational courses are poorly conceived and badly taught. Non-foundational courses were, in our opinion, simply not designed or likely to make a substantial contribution to a student’s familiarity with the overall literary tradition.

Naturally, any categorization of courses entails judgment calls. To avoid criticism that conclusions reached about increased specialization and theory were exaggerated, we followed a generous policy of classifying all courses of ambiguous status as foundational. Thus, the conclusions we reached about the fragmentation of the literature curriculum are, if anything, understated. Moreover, a course’s description often alters before its title, leading to frequent encounters with a course that might be called Nineteenth Century Fiction, but is followed by a description centered upon postcolonial theory or relatively obscure authors rather than classic writers and texts. Since we lent significant weight to a course’s title, such discrepancies also conduced toward understatement. Finally, much anecdotal evidence suggests that course descriptions are lagging indicators of what happens in the classroom. Whatever course descriptions reveal about the extent of change, change in actual teaching practice is probably a good deal greater. This is yet another reason for believing that our figures underestimate the degree to which conveying the “big literary picture” is being neglected.

3. We asked about the degree to which interpretation of literary content was colored by postmodern theory and its “race, gender, and class” preoccupations.

Literary studies have traditionally been concerned with the intentions, techniques, and meanings of authors. The recent evolution of literary theory has, by contrast, worked to “de-center” the author, which subordinates the exploration of authorial purpose to the intellectual interests, and often political aims, of academic critics. This has had the pedagogical effect of turning works of literature into “social text” to be mined from a variety of theoretical perspectives for sexual, racial, political, or class significance. The result is often that a student learns more about the thinking of professors than of authors.

The greatest authors are those whose insight and language transcend the particularities of time, place, and background. All good writers can appeal to readers of diverse origin and experience. Thus, while gender, ethnicity, and social class do influence a writer’s work, too heavy an interpretive emphasis on race, gender, and class inevitably coarsens the appreciation of literature as literature. Simply reading through course descriptions is enough to convey a strong sense of a department’s interest in theory and political/social critique. In making our evaluations, however, we sought to fortify (or conceivably undermine) general impressions about various programs with a quantified indicator of postmodernism’s relative importance. Accordingly, we compiled a list of what, for want of a better name, might be called “postmodern terms of art”: words, phrases, and a few individual names, referring to subjects, interests, concepts, theoretical perspectives, and theorists associated with recent schools of literary criticism. We then counted the number of times each of these appeared in the course descriptions of a particular program. (See Appendices for a complete listing of the one hundred fifteen terms, phrases, and names employed.) The next step was to add up the numbers to obtain a cumulative total for each program. Dividing this by the sum total of all the words the course descriptions contained yielded a percentage figure for each department, facilitating program-by-program comparison. Relatively high percentages suggested a stronger emphasis on postmodern literary theory than low ones. (The figures ran from lows of a few tenths of a percent to highs of nearly three percent.)1

Obviously, the appearance of any particular word or phrase on our list indicates little. Many crop up in course descriptions of an entirely traditional nature. But their cumulative presence is a reasonable measure of the extent to which literary theory’s “new sensibility” has permeated a department’s outlook.

4. We did a computerized count of author names to help establish the relative emphasis given various writers. This involved compiling a master list of three hundred ninety prominent English-language authors past and present (see Appendices). We also compiled another list of authors whose names appeared in the third edition of the Norton Anthology of English Literature published in 1974. The authors represented in this edition are exclusively from the British Isles. Though a number of novelists like Jane Austen are omitted, it is a good indicator of which British authors were considered standard around mid-century. We then tabulated the number of times each of these authors was cited in the course descriptions we analyzed.

The first edition of the Norton Anthology of American Literature did not appear until 1979 and already reflected some of the reevaluations of author status spurred by a heightened consciousness of race, gender, and class. To assemble a list of standard mid-century American authors, we therefore relied on American Writers: A Collection of Literary Biographies (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974), which is, with subsequent revisions and updating, still widely considered a standard reference source.

How much teaching literature now centers upon race, gender, and class with respect to author selection and interpretation is a matter of continuing controversy. We believe that approaches to teaching literature more preoccupied with sex, race, and ethnicity than with artistic achievement diminish the likelihood of achieving satisfactory comprehension of the subject. The extent to which race, gender, and class seem dominating considerations is therefore a question we seek to address.

Undoubtedly, considerations of race, gender, and class are more important today than several decades ago. In 1991, however, a nationwide Modern Language Association survey of upper division undergraduate English courses concluded that “professors of English literature continue to base their teaching on works from the recognized body of traditional literature.”2 Although this statement is a study in ambiguity, and the MLA survey has been subjected to some searching methodological criticism, the findings of America’s largest organization of literary scholars necessarily carry weight.3 Because our data record the changing author preferences of undergraduate English departments at a sizable number of leading schools over several decades, they can shed some useful light on the accuracy of the MLA’s contention.

Although it goes against our grain, we followed fashion by sorting our authors into categories based on race and gender, as well as whether they were alive or dead. Seeking to measure the relative stress given different authors and categories of authors, we tabulated the total number of times particular authors were cited in all course descriptions in each of the three years examined.

We then calculated the percentage that these citations comprised of the total number of author citations in each of those years. (Total author citations nearly tripled during the period under review, rising from 1,986 in 1964 to 5,161 in 1989 to 5,724 in 1997.) We refer to the percentage figure thus derived as an author’s emphasis, denoting the relative degree of attention given to him or her (or, in some cases, to a whole category of writers).

Change in author emphasis can be calculated by comparing the emphasis given a writer in different years. For instance, if an author accounted for two percent of all citations in 1964 and one percent of all citations in 1997, he received 50 percent less emphasis in the latter year than in the former. Changes in emphasis accorded to groups of authors can be similarly calculated. While such changes may reflect various factors (for example, a serious revaluation of an author’s work), they also shed light on how preoccupation with race and gender influences author and theme selection.

5. To assess the changing emphasis given to authors, especially the most prestigious, we counted the number of courses exclusively concerned with their work. In the three years we examined, a total of only thirty-three authors had at least one entire course devoted to them.

With respect to our counts of author citations and single-author courses, we note a methodological caveat.

In a free elective system, which most English departments have more or less embraced, the probability of a student encountering any particular author in a “random walk” through the curriculum is a function of the proportion of all courses and/or reading assignments devoted to that author. Since 1964 there has been a 74% increase in the number of listed courses and a 188% increase in the number of author citations. An author’s statistical “market share” (that is, the likelihood of his or her being read by the “randomly walking student”) will thus decline unless the number of courses, or assignments, dealing with that author grows as rapidly as does the total number of courses and/or readings. The growth of courses dealing with most prominent authors has not kept pace with overall course growth.

Of course, the process of course and author selection is not actually random. Student preference and convenience reshape the odds, as does faculty advisement. We don’t have data about these factors, but we don’t believe they affect the overall significance of our findings. More likely the patterns of student interest, scheduling, and advisement tend to evolve over time in the same direction, if not to the same extremity, as author and course listings. They may sometimes even reinforce the trends displayed by the listings.

For example, most undergraduates are likely to develop their literary tastes in the process of sampling courses and readings. Thus, while student preferences influence course selection, course availability also helps shape student preferences.

Student convenience largely depends on how frequently and when a course is offered, plus its perceived difficulty. Survey courses, major author courses, and foundational courses have traditionally tended to be scheduled most frequently and allowed higher enrollments, giving them a convenience advantage in attracting students. Nonetheless, the more courses that are listed, the more that compete for scheduling. Faculty members who have troubled themselves to develop new courses will almost certainly want them taught. As courses multiply, surviving survey courses are thus likely to lose at least some of their traditional convenience advantages. In addition, as we’ll see, courses covering broad subject matter have not only declined proportionally, but in absolute number as well. There are now fewer of them left to compete for places in the schedule with specialized electives.

Advisement is driven by faculty judgment and self-interest (i.e., procuring enrollments for the courses faculty members wish to teach). But what better indicator of changing faculty judgment and self-interest can there be than the courses professors choose to introduce into the curriculum? Obviously, some advisors will better serve their students than others, but there is no reason to think that advisement as a whole will go strongly against the curriculum’s grain.

In sum, while we acknowledge that a one-to-one relationship doesn’t exist between author emphasis—as we measure it—and the actual exposure any author receives, we are confident that author emphasis is a serviceable measure of such exposure and its changes over time.

6. We also investigated the extent to which the study of film and television is replacing that of literature. To answer this question we counted the number of courses devoted entirely, or in part, to these subjects in each department in 1964, 1989, and 1997. Our position is not that film and television are unworthy of academic study, but that they do not comprise literature. Their presence in English programs thus diverts students from literary study. (There are, of course, instances when viewing a treatment of a Shakespeare play or a Jane Austen novel can be a useful adjunct to a literature class, but that is different from the study of film per se.)

Rigor

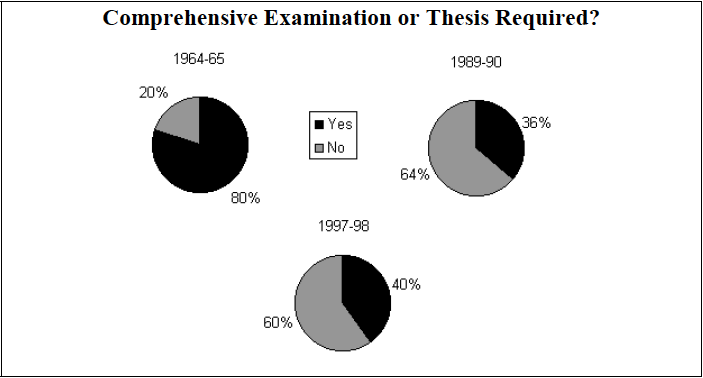

Our interest here was in how much was asked of students majoring in English, particularly whether they were required to pass a comprehensive exam or complete a thesis.

Theses and comprehensive exams are not equivalent in their effects. A comprehensive exam is generally synthetic, demanding the integration of a wide range of disparate knowledge. A thesis, by contrast, usually requires the in-depth treatment of a narrower subject. Ideally, of course, both demand analytic capacities that go well beyond those needed simply to pass individual courses.

The Study’s Framework

Years Surveyed

This study does not reach as far back into the century as our general education report, which included the years 1914 and 1939. Instead, we focus on the period encompassing the most dramatic curricular changes revealed by that study. Hence, our baseline is the 1964–65 academic year, the threshold of the campus revolutions that challenged so many of the assumptions about what it means to be an educated person. From there we jump a quarter-century ahead to the 1989–90 academic year, when deconstruction and other voguish literary perspectives had gained dominance in many English departments. We conclude with the 1997–98 academic year, when we began our research. (We have checked current college websites and noted in the individual departmental profiles any significant changes in majors that have occurred since 1997–98.)4

Programs Surveyed

Our general education study also covered a larger number of schools. Specifically, it looked at fifty elite institutions equally divided between twenty-five prestigious liberal arts colleges and twenty-five leading public and private universities selected on the basis of their appearance in U.S. News & World Report’s listing of America’s top universities and colleges in 1989. Here we confine ourselves to the colleges.

At major research universities, undergraduate English majors are inescapably influenced by the proximity of graduate programs preoccupied with literary theory. We wanted to focus on the purest examples of undergraduate instruction. We picked liberal arts colleges of the highest reputation because their graduates are most likely to rise to cultural and political influence, and because they act as institutional trendsetters for colleges of lesser acclaim.

We examined the English programs at the following twenty-five colleges: Amherst, Barnard, Bates, Bowdoin, Bryn Mawr, Carleton, Colby, Colgate, Davidson, Grinnell, Hamilton, Haverford, Middlebury, Mount Holyoke, Oberlin, Pomona, Smith, Swarthmore, Trinity, Vassar, Washington and Lee, Wellesley, Wesleyan, William and Mary, and Williams.

Department-by-Department Analysis

There is another significant difference between our general education survey and this one. In order to make our basic point about general education patterns as forcefully as possible, we refrained from an analysis of specific schools. In this report, we supplement our description of the overall pattern with a school-by-school review that highlights strengths, weaknesses, and trends. As it turns out, some very significant differences exist among the departments examined.

Our call for higher education reform has gained momentum since 1996. There are now many more trustees, donors, and academic officials who share the NAS’s concerns and are willing to act on them. In light of this development, we thought it important not only to make available our findings on general trends, but also on the extent to which individual colleges participate in them.

With this in mind it should be understood that there are some things a catalogue study can’t uncover, particularly the quality of teaching. It is also worth noting that all the departments we reviewed had fine courses, and at least some faculty members with excellent teaching reputations. No doubt, an unusually discerning student could get a superb literary education at any of them. Unfortunately, literary discernment is not something most beginning English students come equipped with. Rather, it is what a serious study of literature should be designed to cultivate.

Results of the Study: Losing the Big Picture

The trends revealed by the data are very similar to those documented in The Dissolution of General Education, and paint a portrait of contemporary undergraduate English programs that is not particularly flattering.

Structure

In 1964, the typical English department in our sample offered a tightly structured major that channeled students through a small number of introductory courses collectively comprising a sizeable percentage of all courses to be taken. The result was a substantial correspondence in the readings encountered by students, dominated by standard authors and classic works. To know a student had majored in English would have been to know largely what he or she had read. By 1997, however, an undergraduate literary core, and the common expectations about literary cultivation that sustained it, had essentially evaporated.

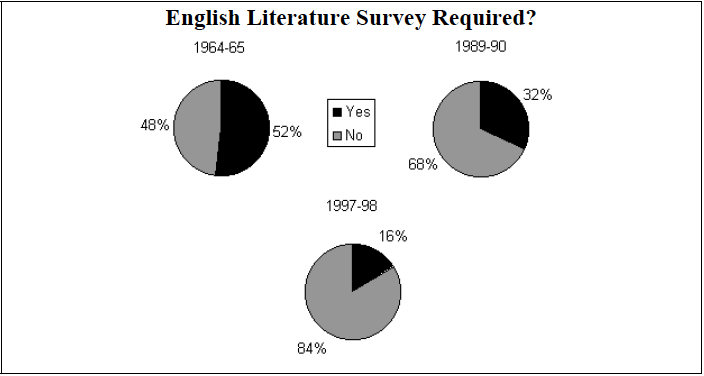

Take, for example, the steady fall in the number of departments requiring completion of a basic survey course. In 1964, thirteen programs made this stipulation, in 1989 eight and, in 1997, just four—Carleton, Davidson, Grinnell, and Smith. Smith alone bucked the trend, having actually introduced its requirement—two full semesters of English literature— between 1989 and 1997. During the same period, however, Bates, Bryn Mawr, Colby, Colgate, and Pomona dropped their required surveys.

A sense of what has been eliminated from the literary education of many students can be gleaned from the titles and descriptions of some of the requirements dropped after 1989. For example, there was Colby College’s two-semester Major British Writers survey, which took students from “Beowulf to Milton” and then from “Dryden to the beginnings of the modern movement.” There was also Colgate’s three-semester survey sequence beginning with a two-part Survey of British Literature from “Old English literature…[to] the middle of the eighteenth century with Alexander Pope” and from the “later eighteenth century…[to] modernism in the early twentieth century,” plus a single semester “Survey of American Literature” from “the early colonial period to the Civil War.” And there was Pomona College’s two-semester Major British Authors survey guiding the student through “a close study in historical context of selected works by writers from the Anglo-Saxon period through 1660, including medieval lyrics, Chaucer, Sidney, Spenser, Shakespeare, Donne, Herbert, Marvell and Milton,” followed by “a close study in historical context of selected works by such 18th and 19th century writers as Swift, Pope, Fielding, Johnson, Austen, Wordsworth, Keats, Brontë, Browning, Dickens, G. Eliot, Hardy, and Yeats.”

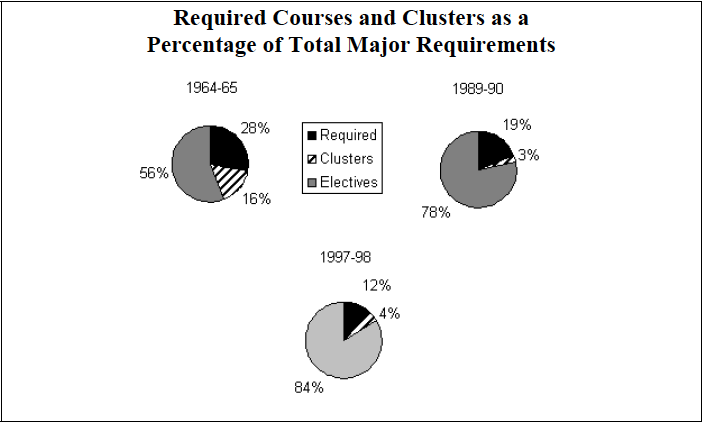

The pattern is equally striking if one looks at all requirements, whether surveys or not, plus clustered courses. In 1964, on average, 43% (44% on the pie chart due to rounding)5 of the total course work of a student majoring in English consisted of such courses, usually dealing with major authors, works, and periods. For instance, a cluster at Pomona prior to1989 consisted of a one-out-of-three choice among Advanced Study in Mid-Nineteenth Century Literature, Advanced Study in Late Nineteenth-Century American Literature, and Advanced Study in Early English Literature. However, by 1989 the proportion comprised by requirements and clusters had dwindled to 22%, and by 1997 to 17% (16% on the pie chart due to rounding).

Moreover, the content of the remaining courses can no longer be reliably expected to be about major authors, works, or periods. Instead, theory begins to intrude, as in a clustered course at Oberlin described in the 1997 catalogue as “designed to develop competency in understanding and applying literary criticism at a time when diversity of critical and theoretical perspective is increasingly central to the study of literature.” Or in a two-semester required junior seminar at Haverford emphasizing “the range and diversity of the historical tradition in British and American literature” and “critical theory and practice as it has been influenced by hermeneutics, feminism, psychology, semiology, sociology and the study of cultural representation.”

In addition, in 1964 twelve programs required or clustered a course on Shakespeare. By 1989 only five did. And by 1997, only four—Hamilton, Middlebury, Smith, and Wellesley—still retained them. Between 1989 and 1997, Bates and Swarthmore dropped Shakespeare requirements, while Hamilton added a “clustered” Shakespeare course. Shakespeare is, of course, frequently included as a part of multi-subject courses, but as we’ll see, evidence suggests that he is declining in curricular prominence across the board.

While all this was going on, the total number of free electives increased markedly. In 1964, the average of listed courses was forty-two per department. By 1997, this figure had grown to seventy-three, an overall increase of 74%. There was, however, a good deal of variation from school to school. For instance, at Grinnell the total number of courses actually declined from forty-two to thirty-nine, and at Oberlin from forty-six to forty-five. At Mt. Holyoke, Wellesley, and Williams, courses increased by less than 30%. On the other hand, at Bates and Colgate the number of courses more than tripled.

Because of this substantial increase in available courses, students necessarily took a smaller percentage of a department’s total offerings. In both 1964 and 1997, students typically completed about ten courses. Accordingly, in 1964, students took, on average, about one-fourth of all courses listed. In 1997 they took only about one-seventh.

The expansion of distribution requirements only partially mitigated the trend away from a common literary core. As in the case of general education, the dwindling of prescribed or clustered offerings has been associated with a multiplication of distribution categories, requiring students to choose at least one course among the sizable number grouped under each distribution heading. Subject matter distributions are course categories distinguished by related content. Some examples are English Renaissance drama, Eighteenth-century fiction, Romantic poets, and the Victorian novel. Stratification distributions are course categories differentiated by the level of proficiency expected of students. For instance, “200,” “300,” and “400” level courses are usually for sophomores, juniors, and seniors, respectively.

By 1997, departments were more likely to stratify their course offerings than they had been earlier. Twenty programs were organized in this way in 1997, as opposed to only six in 1964 (and eighteen in 1989). In the absence of the more clear-cut course sequences of the earlier period, this stratification helps preserve some curricular coherence. In 1964–65, there was a total of twenty-two subject matter and twelve stratification distribution categories among the majors we examined. By 1997–98, the number of subject matter distributions had risen to sixty-nine and stratification distributions to thirty-three, tripling their overall amount.

The Narrowing of Content

There are other indicators that English departments increasingly emphasize specialization over broad familiarity with the literary tradition. For example, in 1964, only seven of the twenty-five programs demanded that students concentrate their work in a specific area of literary scholarship, and as recently as 1989 only eight did. By 1997, however, fourteen programs demanded this kind of specialization.

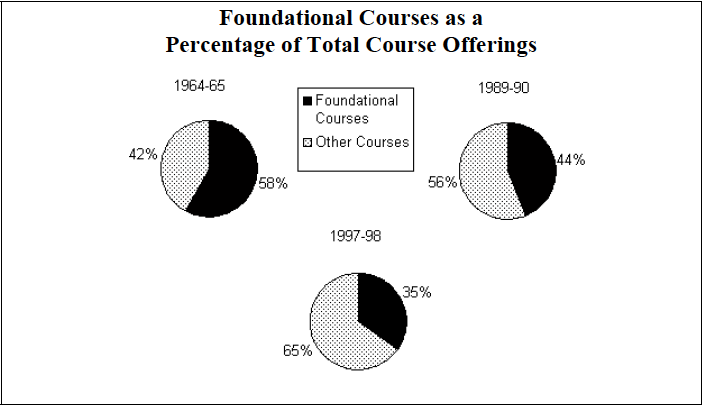

Equally significant, the percentage of foundational courses has declined steeply. In 1964, on average, 58% of the courses available to English majors were foundational. By 1989, the figure was 44%, and, by 1997, 35%. But there was also very considerable variation among departments. At a few—Colgate, William and Mary, Hamilton, Pomona, and Washington and Lee—foundational courses still comprised nearly half of those offered. At another, Grinnell, they were actually a small majority. By contrast, at Amherst, Barnard, Swarthmore, Trinity, Wesleyan, and Williams, foundational courses comprised less than a quarter of the total. (At Trinity they were a mere 16%.)

This is not just a proportional decline; since 1989 it has been an absolute one as well. Between 1989 and 1997, the total number of courses grew by 13%, but the number of foundational courses fell from 709 to 633, a dip of 11%. To be sure, five departments—Colgate, William and Mary, Hamilton, Pomona, and Williams—added a small number. And one, Middlebury, increased its number of foundational courses by more than a third. On the other hand, their numbers fell in fourteen other programs, some very sharply. For example, at Bryn Mawr nearly half the foundational courses disappeared from the catalogue between 1989 and 1997. Thus, not only is new subject matter being added, but traditional material is being removed.

More than anything else, the increasing dominance of specialized offerings represents a shift from requirements reflecting undergraduate interest in acquiring a broad frame of reference, to ones that reflect faculty interest in pursuing recondite research. With a far greater emphasis on publication than in 1964, even at “teaching institutions,” professors feel strongly pressured not to divert too much time from their research. This usually means trying as much as possible to teach whatever one happens to be researching. And this usually means peppering the catalogue with narrow specialty courses.

But a growing preoccupation with the arcane and ideological is surely at work here as well. Once specialization becomes mixed with identity politics and the sexual obsessiveness of postmodern theorizing, course content can go off in some rather peculiar directions.

Academic Exotica

Some of the more exotic headings under which many courses now fall are set out below. While by no means do all new courses introduced since 1964 take such themes, a great many do.

Sex, Sexuality, and Bodies

Amherst offered Representing Sexualities in Word and Image, “which traces the cultural production of sexual knowledge over the last century, beginning with print and video representations of the AIDS crisis and concluding with Whitman’s daring projections of same-sex desire in the ‘Calamus’ poems first published in 1860,” and Studies in the Literature of Sexuality. Wesleyan’s History of Sex “will focus closely on a series of problems in the history and representation of sex in Europe and America.” The course description fails to mention a single author, literary work, genre, or literary movement.

Swarthmore’s Renaissance Sexualities course description claims that “[t]he study of sexuality allows us to pose some of the richest historical questions we can ask about subjectivity, the natural, the public and the private.” Swarthmore also offered Illicit Desires in Literature, which looked at “some differences that race and gender have made in the literary expression of a range of sexual desires,” and Modern Bodies in the Making: The 19th-Century Novel, which examined “productive and reproductive labors and sexualities,” among other things. Williams’s American Genders, American Sexualities investigated “how sexual identities, desires, and acts are represented and reproduced in American literary and popular culture.” Trinity offered a course in 19th-Century Novel: Fiction and the History of Sexuality, which “explores the characteristics of emerging genres . . . as they shaped theories of gender difference and the Victorian body and reconfigured conflicts between forces of patriarchy and feminism, reform and revolution, professionalism and class.” The course description gives a sense of the instructor’s priorities when, before mentioning any novels, it informs us that the course includes “readings from Darwin, Mill, Freud, and Foucault.”

Other courses exploring the nexus between psychology and sociology, with little apparent reference to English literature, were Swarthmore’s (Asian) Ethnicity and (Hetero) Sexual Normativity and Haverford’s Gender and Feeling in Early American Culture. In a similar vein, Barnard offered Body and Language, described as “[a]n examination of major discourses on corporeality and the body’s cultural significance.” Wesleyan’s version of this course was Reading Bodily Fictions, some of whose themes included “literary representations of hysteria, ‘foreign’ bodies and the politics of race, diseased bodies and fictions of health and normalcy, discipline and the modern body, feminist theory and reproductive technologies.” Restricting its anatomical scope, Trinity offered Sacred Female Body, which examined “contemporary revivals of the iconology and ideology of the sacred female body.”

Gothic Literature

Formerly on the periphery of literary studies, Gothic literature has come into the mainstream in recent years, with Horace Walpole (The Castle of Otranto), Mary Shelley (Frankenstein), and Bram Stoker (Dracula) among the favorite authors. In 1997–98, Amherst offered a course in The Politics of the Gothic in the English Novel, which “will study such genres as the sentimental, gothic, and realist novel, with particular attention paid to . . . the formation of class, gender, and sexuality.” Bates offered The Gothic Tradition, in which “[p]articular emphasis is placed on the politics of the Gothic: on its relation to revolutionary movements, on its representations of intimacy and violence, and on the ways in which Gothic novelists both defend and subvert prevailing conceptions of sexual and racial difference.” Bates also taught Frankenstein’s Creatures, and Swarthmore Gothic Possibilities. Wesleyan’s contribution to the field, Victorian Gothic (Before and Beyond), stressed the common economic theme: “In the first volume of Capital, published in 1867, Marx writes that ‘capital has one sole driving force, the drive to valorize itself .… Capital …, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labor, and lives the more, the more it sucks.’ ”

Cultural Studies

Some institutions, like Wesleyan, concentrated on offerings that seem better housed in the sociology department. The course description of Reading Television informs students that the course, contrary to expectation, will indeed require work: “Despite the fact that the course focuses on what has been called ‘mind-candy,’ prospective students should know that this will be a rigorous course, requiring a serious commitment of time to reading about, watching and analyzing television texts.” A course called Rebel Without a Cause/Sweet Little Sixteen: The Social Construction of the Teenager in American Culture, 1948–64 studied “the social construction of the teenager . . . in an attempt to understand why postwar America constructs this category and defines it as a consumer culture.” The title of a course like The Child, the Postcolonial, and the Problem of Authority leaves one wondering how it relates to English literature. Perhaps in an attempt to provide balanced treatment of the sexes in an otherwise highly feminized discipline, Trinity offered a single sociology-like course entitled American Masculinity in Postwar Popular Culture.

For its part, Bryn Mawr had a course on Landscape Art in Cultural Perspective. The course’s description, although expansive, fails to show how course content relates to the reading of novels, plays, and poetry: “An exploration of some of the arts of literary landscape, with particular attention to cultural factors which shape the perception, representation, manipulation, and appreciation of landscapes and to the evolution of landscape art within the larger rhythms of cultural history.” Wesleyan had Women, Sociability and Solitude, whose course description fails to mention any author or literary work, although there is an allusion to the “writings of women from the modern industrial era.” Trinity offered The Mask: Forms of Minstrelsy in American Popular Culture, whose description tells us that “this class will ask students to examine how masks have operated in the American culture industries—as disguise, as metaphor, and as parody.” Williams offered a course simply called Wonder:

We tend to imagine “wonder” as a non-historical, pre-rational category, as what inspires and perhaps lingers beyond the cold act of critical analysis. In this team-taught discussion course, we will consider wonder as an eminently analyzable concept, a concept which raises provocative questions about the historical nature and limits of our own distinctly modern forms of critical engagement. Most broadly, the course will look to the “naïve” category of wonder to reflect in a sophisticated way on the vexed relation between theory and history.

Queer Studies

This is a new field that made a strong appearance after 1989–90, with Swarthmore offering Lesbian Novels Since World War Two, Lesbian Representation, and Queer Media. Other schools did their part, for example Bryn Mawr’s Lesbian and Gay Literature, Colby’s Art and Oppression: Lesbian and Gay Literature and Modern Society, and Amherst’s Black Gay Fiction. Wesleyan listed Queer Theory: “A close study of a fast developing field of theory concerned with the sexual practice and ideology and identity in human societies and cultures,” and The Newest Minority: The Emergence of Lesbian-Gay Community and Culture, 1895–1969.

Postcolonial Studies

Another recently popular area is postcolonial studies, which uses literary texts to unmask the exploitation of other cultures by Western societies. Smith, Wesleyan, and Williams each listed a course titled Postcolonial Literature. Swarthmore expanded on the theme with Postcolonial Literature and Theory, and Bates had a similar course, Postcolonial Literatures and Theory. Oberlin advanced further with Post-Colonial Criticism: Theory and Practice, and Bryn Mawr offered Post-Apartheid Literature. Haverford taught Postcolonial Women Writers: “The narrative strategies enabling and sometimes subverting historically and culturally specific negotiations between the claims of postcolonial, class, and feminist politics.”

Race, Gender, and Class

The triumvirate of race, gender, and class has not lost its ascendancy over the years and, based on longevity, may soon be considered traditional. Trinity offered Gender, Race and Ethnicity in Contemporary American Fiction and The Fiction of the Middle Class, while Williams listed Language, Gender, and Power. Haverford taught ‘Race,’ Writing, and Difference in American Literature and Gender and Theatricality in the Restoration and 18th Century. Barnard picked up the theme in the same period with Race and Gender in the Age of Johnson. Swarthmore offered Romanticism and the Performance of Gender and “Whiteness” and Racial Difference, and Smith listed Fairy Tales and Gender. Amherst’s contributions included Reading Gender, Reading Race and Issues of Gender in African Literature. Wesleyan offered Modernity, Gender, and War and Other Than Black and White, while Bryn Mawr listed The Multicultural Novel (Women Writers). Bates taught Reading “Race” and Ethnicity in American Literature. Wellesley had a similar course, Race and Ethnicity in American Literature, as well as Race, Class, and Gender in Literature. Colby offered a seminar, Class in America. As previously noted in other contexts, Williams taught American Genders, American Sexualities and Haverford Gender and Feeling in Early American Culture.

Examined quantitatively, preoccupation with postmodern theory and race, gender, and class scholarship was greater in 1997 than it had been in 1989. In the earlier year, postmodern terminology comprised 0.84% of the text of the average department’s course descriptions, a figure that by 1997 had climbed to 1.24%, an increase of nearly 50%.

On the other hand, the departments we surveyed differed substantially in the extent to which their course descriptions reflected a “postmodern sensibility.” In 1997, the English departments of Swarthmore, Wesleyan, Bryn Mawr, Haverford, and Barnard had a three-to-fifteen times higher frequency of postmodern terminology than did the English departments at Grinnell, Colgate, Davidson, Middlebury, and Washington and Lee.

Not surprisingly, a department’s position with respect to this “postmodernism scale” generally coincided with other structural and content indicators. That is to say, those departments with a higher number of basic surveys and foundational courses also tended to have course descriptions with less postmodern terminology than those with fewer surveys and foundational courses. Less predictably, there was little relationship between a department’s position on the postmodernism scale and the types of authors cited in course descriptions (see below).

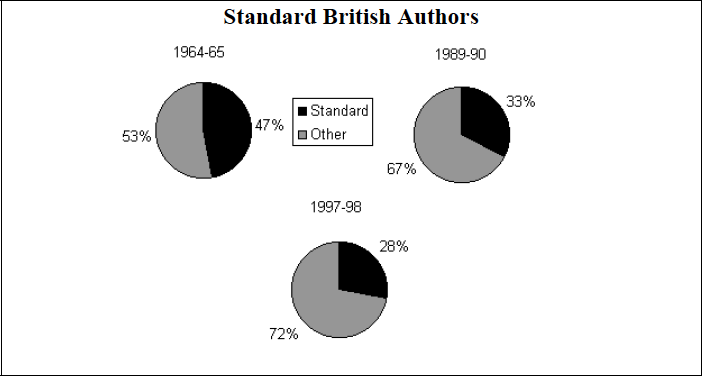

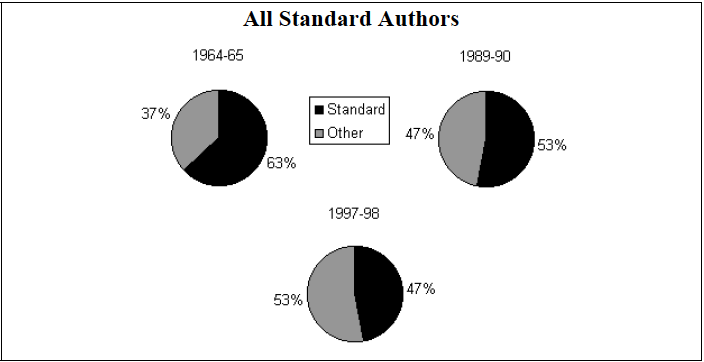

Changes in Relative Author Emphasis

The biggest change since 1964 has been the relative de-emphasis of classic British and Irish authors, the group comprising the most important single component of the English literary tradition. While 47% of the names cited in 1964 course descriptions were authors found in the third edition of the Norton Anthology of English Literature, that figure fell to 33% by 1989, and 28% by 1997. This represents a decline of 40% in relative emphasis. The decline affected almost every leading Norton author including Shakespeare, whose citations dropped from 4.7% of the total in 1964, to 3.3% in 1997, a loss in emphasis of almost one third. Other classic authors slipped further. Chaucer, for instance, lost almost half the emphasis he had received in 1964, falling from 3.0% to 1.6% of the citations. Milton fared even worse, sliding from 3.3% of all citations in 1964 to 1.3% in 1997—a loss of more than three-fifths of his earlier prominence. Among other big losers were Wordsworth, who lost more than a third of his 1964 prominence; Donne, who lost almost half; Keats, who lost half; Swift, who lost more than half; Byron, who lost three-fifths; Pope, who lost slightly more than three-fifths; and Matthew Arnold, who lost almost two-thirds. The only highly rated Norton white-male author to register a gain was James Joyce, who rose from 0.8% of all citations in 1964, to 0.9% in 1997.

A similar pattern emerges when single-author courses are examined. In 1964, a total of forty-five courses were devoted to Shakespeare. Every department but Hamilton’s had one, and fourteen departments boasted two or more. By 1997, this number had risen to fifty-eight, with every department represented and all but three with more than one course on the Bard. The total number of Shakespeare courses therefore grew by about 29%. But since the total number of courses grew by 74%, the overall percentage of courses devoted to Shakespeare shrank from 4.3% to 3.2%—a loss of about one-fourth in emphasis. There were twenty-five Chaucer courses in 1964, and twenty-nine in 1997—an increase of 16%, but in the context of the huge multiplication of all courses, a loss in emphasis of a third. Milton courses grew from fifteen to eighteen, an increase of 20%, but also a loss in emphasis of nearly a third.

Shakespeare probably represents one of those few instances in which student preference operates as a strong counterweight to changes in curriculum structure. Shakespeare is the one author whose greatness is proverbial, and courses about him and his work remain popular, though the diminution of required Shakespeare courses has no doubt had an impact. This is unlikely to be true, however, with respect to Chaucer, Milton, and most other literary masters.

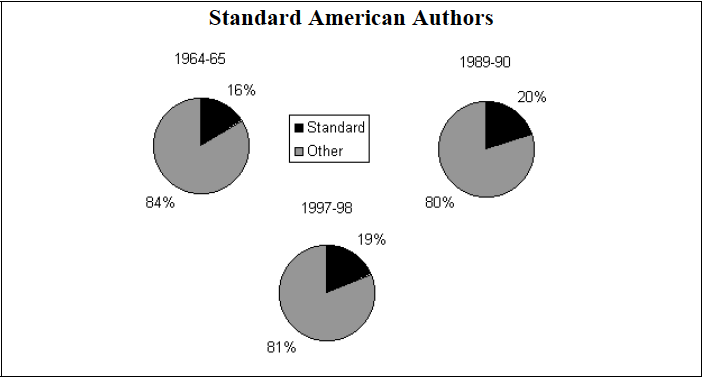

The trend with respect to formerly standard American authors has been more complicated. Between 1964 and 1989 the percentage of citations attributable to authors found in American Writers: A Collection of Literary Biographies actually rose from 16.3% to 20%. Between 1989 and 1997, however, it fell back to 18.4%. Of the traditionally classic American authors, Poe suffered most: by sliding from 1.0% to 0.5% of all citations, he lost half the emphasis he had received in 1964. Hawthorne and Emerson each suffered slightly more than a two-fifths diminution in emphasis; the former descended from 1.2% to 0.7% of all citations, the latter from 0.9% to 0.5%. Melville and Whitman each dropped about a third, from 1.2% to 0.8% of all citations. Twain fell a bit more, from 0.8% to 0.5%.

On the other hand, among standard American authors, gainers counterbalanced losers to a greater extent than among their British equivalents. While none of the 1964 top twenty-five standard British authors had an improved standing in 1997, four of the top twenty-five Americans did. Emily Dickinson, for example, rose from 0.6% to 0.8% of the citations, a one-third gain in emphasis; Henry James from 0.9% to 1.2%, a gain of a third; Faulkner from 0.8% to 1.1%, gaining slightly more than a third; and Hemingway from 0.4% to 0.7%, a remarkable threequarters increase in overall prominence. Though generally overlooked in debates over changes in the literature curriculum, a fairly pronounced trend toward its Americanization appears underway. Thus, in 1964, the top twenty-five American authors had only 41% of the citations claimed by the top British twenty-five; by 1997, they had 71%.

But the far more important trend is literary scholarship’s progressive feminization. Indeed, one of the reasons that the standard American authors list of 1964 lost less ground than its British counterpart is the larger number of women writers on it. Prior to the eighteenth century, female English-language authors of any prominence were almost nonexistent, and it is not until the nineteenth century that their numbers really increase. Because American literature only blossoms during the nineteenth century, it includes a greater proportion of standard female writers. Of the one hundred and twenty-two British authors represented in the third edition of the Norton Anthology only four—Emily Brontë, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Christina Rossetti, and Virginia Woolf—are female. Of the ninety-seven authors listed in American Writers, fourteen are women and, of these, six—Willa Cather, Emily Dickinson, Flannery O’Connor, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, and Edith Wharton—gained appreciably in emphasis between 1964 and 1997.

Our statistics also clearly confirm the reality of “race” as a driving factor in revamping literature programs. The fact that the United States has produced many more “authors of color” than the British Isles is another reason for the English curriculum’s increasing Americanization. Many African-American writers have gone from little or no notice in 1964 to substantial visibility in 1997. Among the better known, Langston Hughes, Frederick Douglass, and Ralph Ellison—each unmentioned in course descriptions in 1964—accounted for 0.3%, 0.4%, and 0.4%, respectively, of all author citations by 1997. Richard Wright went from 0.1% in 1964 to 0.6% in 1997.

Taken together, gender and race have altered literature curricula in some startling ways. For example, as far as citations can attest, African-American novelist Toni Morrison is now considered—by English professors at least—to be the sixth most important author in the history of the language. Her seventy citations, amounting to 1.2% of the 1997 total, put her ahead of every American writer in the top twenty-five in 1964, as well as all the British ones except Shakespeare, Chaucer, and Milton (who edged her out by four citations). Moreover, of the top six authors in 1997, three: Jane Austen (ranked third with seventy-eight citations), Virginia Woolf (ranked fifth with seventy-two citations), and Toni Morrison, are women. Given the heavy disproportion of male to female authors over the course of English literary history, this is certainly an astonishing outcome—even if the literary excellence of Austen, Woolf, and Morrison is granted. To put this in broader perspective, on the basis of citations, Austen, Woolf, and Morrison now receive about twice the attention of Pope (thirty-six citations), Swift (thirty- six), Twain (thirty-one citations), Fielding (twenty-nine), Poe (twenty-nine), and Dryden (twenty-three).

Toni Morrison is a Nobel laureate, and in a century or so may be seen as standing head and shoulders above Twain, Fielding, Poe, Dryden, Pope, and Swift. But hers is not the only high rating to give one pause. Zora Neale Hurston, albeit a gifted writer of the Harlem Renaissance, also ranks startlingly ahead of Twain, Fielding, Poe, Dryden, Pope, and Swift. Even obscure Aphra Behn—a late seventeenth-century female playwright—ranks ahead of Shaw, Marvell, Pound, Scott, Auden, Beckett, Nabokov, and Kipling. A look at the changing prominence of some of English literature’s most celebrated literary relatives is also illuminating. Take Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, for instance. In 1964, Robert received sixteen citations and Elizabeth none. In 1989, Robert had eighteen and Elizabeth three. As of 1997, Robert had sixteen and Elizabeth fourteen. Or Dante Gabriel and Christina Rossetti. In 1964, the score was three to nothing in favor of Dante Gabriel. In 1989, it was four to four. By 1997, Christina led twelve to seven. Or Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley.

In 1964 Percy was cited sixteen times and Mary none. In 1989, it was thirty-six for Percy and sixteen for Mary. In 1997 they had twenty-five citations apiece. One can argue somewhat over the artistic justice of these reevaluations, but not over the forces driving them.

We can best understand the role gender and race have played in changing the face of undergraduate literary studies by looking at living authors. Six hundred years of literary history impose restraints on what even the most assiduous renovators of the canon can accomplish. There is always room for reevaluating some writers and promoting others into prominence, but the great body of established classics cannot entirely be ignored. With respect to contemporary authors, one has a freer hand. Reputations are not yet solidified, scholarly opinion is uncongealed, and almost any disagreement can be ascribed to differences in taste. To discern most clearly the criteria underlying current literary assessment, look to its judgments about living authors.

The three most cited living authors are all “women of color”: Toni Morrison, followed by the African-American novelist Alice Walker and the Chinese-American novelist Maxine Hong Kingston. Walker and Kingston, with twenty-eight and twenty-four citations, respectively, receive twice as much emphasis or more than all but three of the white male authors included among the top living twenty-five. (The top-ranked twenty-five living authors actually included twenty-six individuals because of a tie between bell hooks and Joyce Carol Oates for twenty-fifth place.) Walker, for instance, gets more than twice the attention accorded Nobel laureate Saul Bellow (cited twelve times), three times more than Norman Mailer (cited seven times), and seven times more than John Updike (cited four times). Comparisons of these authors with Maxine Hong Kingston yield roughly the same results.

The fourth-ranked living author is Salman Rushdie, another “person of color,” who with nineteen citations also holds a significant lead over Bellow, Mailer, and Updike. Places five, six, and seven, which do belong to white males, are occupied by postmodern novelist Thomas Pynchon (seventeen citations), Philip Roth (sixteen citations), and the Irish poet and Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney (fifteen citations). Overall, white males comprise a minority of eleven of the twenty-five top living authors. And they only average 9.5 citations apiece, compared to 14.5 for minority and female writers. In addition, of the fourteen female authors on the list, seven are “women of color.” These seven average 20 citations apiece; the white female writers average only 8.4.

Also revealing is the change in emphasis since 1989. Of the eleven white male authors on the list, eight lost in emphasis while only three gained. (Salman Rushdie gained more than their combined total.) Among the fourteen female authors, ten were gainers and four were losers. Subtracting the losses from the gains, the female authors increased their collective emphasis by 0.78%. Similarly, subtracting losses from gains, the male authors lost 0.28% of their earlier emphasis. Taken alone, the white males dropped by 0.47%.

Some of these highly rated female authors may be dismissible as tokens regularly drafted into service out of professorial determination to assign some writer of the correct sex or hue. But their exaggerated stature is symptomatic of something deeper and more troubling: English departments have abandoned their true purpose. The compulsion to promote the merely talented to the rank of greatness, and the deservedly obscure to conspicuous note, exposes a field where championing causes—especially radical feminism—routinely trumps the claims of art. This has effects that go far beyond the works assigned. While accepted classics remain a large, if dwindling, body of all undergraduate readings, their interpretation is frequently hacked and skewed to make political points. Shakespeare may have been a white male, but—with the appropriate postmodern mutations—he can be enlisted in any number of gender-bending crusades. How much of his liberating vision and stunning beauty survive the faculty press-gangs is anyone’s guess.

What are we then to make of the MLA’s contention that “professors of English literature continue to base their teaching on works from the recognized body of traditional literature”? That depends on the meaning we give its ambiguous phrasing. If it means that standard authors and works still make up a substantial part of the English curriculum, it is true, although they no longer constitute a majority, as in 1964, when they represented 63% of authors cited. In 1997, the Norton and American Writers standard authors together comprised only 47% of all authors cited. If, on the other hand, it means that the changes in authors assigned have been minor, or that the undergraduate curriculum continues to guide students through the works of standard authors, then, with respect to the majority of departments surveyed here, the MLA’s claim is largely false. But if “to base” means what most would take it to mean—that is “to make or form a base or foundation for”—the MLA’s contention is wholly untenable. The faculty sensibilities displayed in course descriptions and changing author emphasis show less desire to have the students learn from, or even about, standard authors, than to use these authors’ works as “texts” (or pretexts) for countercultural preaching. This now seems to be the major purpose of a great many programs ostensibly about literature.

In this context, it is interesting to note that several departments with a strong postmodern tilt nonetheless cited higher percentages of standard authors than some seemingly more traditional departments. For instance, in 1997 Wesleyan ranked third in this respect and Haverford seventh. But this is not as strange as it may appear at first glance. After all, it is not difficult to mesh the study of standard authors with postmodern interpretative approaches, as, for instance, in Haverford’s Gender and Theatricality in the Restoration and 18th Century, which focuses on “gender roles and sexuality, and the social, economic and political ideologies that affect representation,” while citing Dryden, Wycherley, Behn, Congreve, Gay, and Fielding, half of whom appear in the third edition of Norton. Interpretation can also easily become an exercise in debunking, as Shakespeare becomes a shill for English imperialism and Milton a misogynist. As important as the cumulative changes in what is being taught, the changes in how it is being taught may be even more so.

The Rise of Film Studies

Film, a subject usually regarded as distinct from literature, has become a significant field of specialization in some English departments. The study of television and other media has also become increasingly prominent.

In 1964 there were only seven mentions of film or television distributed among three course descriptions (0.3% of the total courses): two at Vassar and one at Barnard. Each course was straightforward, semi-technical, and wholly without theoretical pretense. One Vassar course studied “the contemporary press,” including approaches to reporting, interviewing, and writing. The other explored the production and federal regulation of television and radio programs. The Barnard course taught dramatic writing, considering television, film, and radio, as well as stage scripts.

As of 1989, however, no less than fifty-three courses—3.3% of all listed—dealt with film or television. Of these, twenty-one were solely devoted to film or television, while another thirty-two had film or television as one of their subjects. By 1997, film and television courses had increased to ninety-five, or 5.3% of the total. Thirty of the courses were entirely about film or television, and another sixty-five dealt with these media in part. The study of film is clearly a growth industry among our leading English departments.

Certain departments far exceeded others in their interest in movies and television. A pioneer in this respect, Amherst’s English department already offered ten such courses in 1989, comprising about 13% of its listings. By 1997, Amherst’s total of eleven (13% of its listings) had been surpassed by Swarthmore’s fifteen (13% of its listings) and Trinity’s sixteen (16% of its listings), though Amherst still stood first in having seven courses entirely concerned with these media. Amherst’s numerous film courses included Film and Writing, Studies in Classic American Film, Film Noir and the Art of Hollywood Film, Production Workshop in the Moving Image (including “hands-on exercises with video camcorder and editing equipment”), The Non-Fiction Film, Topics in Film Study, and Production Seminar in the Moving Image. Swarthmore gave major billing to offerings like American Narrative Cinema; Women and Popular Culture: Fiction, Film, and Television; Feminist Film and Media Studies; Film Theory and Culture; Studies in Film and Literature; and the previously mentioned Queer Media, which asks “How do lesbian and gay film and video makers ‘queer’ sexual norms and standard media forms?”

The emphasis given to film, television, and other nonliterary media closely corresponded to a department’s overall orientation. Most departments featuring numerous courses on nonliterary media also displayed strong postmodernist leanings. By contrast, four of the eight departments without film or television courses in 1997—Colgate, William and Mary, Grinnell, and Washington and Lee—were otherwise strongly traditional. This is not a surprising relationship in view of postmodernism’s proclivity to treat all media as “text,” a move that inevitably obscures the distinctiveness of purely literary forms.

Rigor

The number of departments requiring a thesis or comprehensive exam was halved from twenty to ten between 1964 and 1997. This, however, represented a slight improvement over 1989, when only nine departments had such requirements. These raw numbers, however significant, don’t fully reveal the most important part of the story, which, once again, concerns the shift from providing an overview to fostering specialization. Of the twenty English departments with capstone requirements in 1964, all insisted on a comprehensive exam, an exercise designed to ensure breadth of knowledge and ability to synthesize, with Wesleyan requiring both an exam and a thesis. Of the nine programs with capstones in 1989, just five required comprehensive exams, one a thesis, and three vague exercises described by two as “an essay,” and the third as a “project and oral examination.” Of the ten programs with capstones in 1997 only Middlebury, and Washington and Lee required a comprehensive exam, two others expected theses, another gave a choice between an exam and a thesis, two prescribed “essays,” another a “project,” another an “oral exam,” and another a “project and oral exam.” Where once stood a formidable test of general mastery, we now find fuzziness and, perhaps, an invitation to idiosyncratic display.

Conclusion

Despite our findings, the outlook is not entirely bleak. Among the English departments we surveyed, several showed a conspicuous—though not complete—resistance to the dominant trends. It is particularly encouraging that a number of programs like those at Grinnell and Middlebury, which were in fairly good shape in 1989, remained so in 1997. Programs like these provide a continuing example of good practice, giving at least some of the current student generation the foundations necessary to transmit the English and American literary traditions to the next. They give hope for the future.

Still, the overall prospect is discouraging. Most of the English departments of our leading colleges show a greatly diminished interest in familiarizing undergraduates with the Anglo-American literary heritage. This is especially worrisome in an age when television and the Internet lessen the likelihood of students entering college with much knowledge of literature. Many of these programs’ graduates—though no doubt priding themselves on having received a first-class literary education—must actually possess only the most rudimentary knowledge of English literature’s longer history and its greatest writers and works. What they have instead is premature specialization, dubious theoretical insights, and a familiarity with trendy writers of approved identity and outlook who are likely soon to fade from view.

Many of the next generation of America’s writers, scholars, critics, and teachers will come from the ranks of these poorly trained students. Anyone concerned about preserving a creative literary culture has reason to be alarmed.

1 The mantra of “race, gender, and class” indicates the topics of greatest general interest to recent academic criticism. We thus used the terms “race” and “gender” (as well as “sex”), together with their many variations, in our computerized word count. We omitted “class,” however, to avoid confusion with its denotation of a course section. It should be kept in mind that the great majority of words used in course descriptions are those of ordinary English. The percentage of technical words in any specialized publication, in such fields as law, medicine, and science, will always constitute a relatively small fraction of all words used. What we cared about were the differences in frequency with respect to the use of postmodern terminology from department to department, and from year to year.

2 Modern Language Association of America, “MLA Survey Provides New View of Campus Debate,” press release, 4 November 1991.

3 See Will Morrisey, Norman Fruman, and Thomas Short, “Ideology and Literary Studies, Part II: The MLA’s Deceptive Survey,” Academic Questions, vol. 6, no.2 (Spring, 1993).

4 Where a catalogue for the desired year was unavailable, we substituted the closest prior year. Thus, for Smith College and Wellesley College, we used the 1963–64 catalogues instead of those for 1964–65. For Wesleyan University we used 1963–64, 1987–89, and 1996–98. Our analysis of the prevalence of postmodern terminology was restricted to the years 1989–90 and 1997–98 (with the appropriate adjustments for Wesleyan).

5 To derive this figure we counted both specifically required and clustered courses.