Summary

The Vanishing West traces the decline and near extinction of the Western Civilization history survey course in America’s top colleges and universities from 1964 to 2010.

This course, covering classical antiquity to the present, was once part of the undergraduate curriculum’s intellectual bedrock, not only because it was often a graduation requirement, but because it gave narrative coherence to everything else the university taught. In studying the rise of the West, students came to grips with how the arts and sciences encountered in other classes had been shaped. And because Western Civilization had “gone global,” they also learned what made the world outside campus the place it had become. They usually finished with at least a partial recognition of their civilization as a grand monument to human achievement and something with which to identify.

In 1964, the Western Civilization survey course in various guises, along with related courses such as Great Books surveys, were to be found at all the colleges and universities we surveyed. By 2010, the course had disappeared entirely as a requirement at these institutions and was available in some less emphasized form at less than a third of them.

What happened to the study of Western Civilization? Why has it nearly disappeared? What has replaced it? To find out, we examined the requirements of fifty prominent universities and colleges as they were in 1964 and 1989 and as they are today, plus the current requirements of seventy-five additional state universities.

While we found the Western Civilization history survey course in steep decline, we also found a parallel decline of American history survey requirements, and the emergence of what is now widely seen as a substitute for the history of the West, “world history.” Our five main findings are:

1. Western Civilization survey courses have virtually disappeared from general education requirements

2. Even for history majors, Western Civilization surveys are rarely required

3. American history survey requirements for history majors are rare

4. Surveys of American history are not included in general education requirements

5. World history is on the rise

Clearly, many of those who will eventually assume positions of opinion leadership in our society as teachers in our schools, or as participants in public life, are no longer learning about their civilization’s great story, its triumphs, its vicissitudes, and its singular role in transforming the human condition. What is the future of a civilization whose heirs have largely become blinded to its history? And what can we do to revive the study of Western Civilization?

The widespread emphasis on “multiculturalism” is an inadequate answer. That’s because, in practice, multiculturalism leaves students ill-equipped to understand the context of their own lives or the world around them. Western Civilization is so interconnected with and influential in the rest of the world that students who are left with scant knowledge of it can achieve at best only a superficial understanding of the larger picture.

Reviving the Western Civilization survey in the form that served earlier generations probably is neither feasible nor desirable. Historical scholarship, including knowledge of the West’s interactions with other civilizations and cultures, has progressed. An up-to-date survey would have to take account of this new scholarship.

But a historical overview of the Western ascent toward freedom, scientific and technology mastery, and world power, is no less essential to the current generation than it was to those past.

The Vanishing West invites a new dialogue on how best to resume the work of teaching a rounded overview of our civilization to young men and women on whom the responsibility will fall to maintain and improve it. We offer twenty-three recommendations aimed at better studying the problem, rebuilding the curriculum, and repairing the graduate education pipeline, so that the history profession will again begin to prepare faculty capable of, and interested in, teaching about the broad course of Western history.

“The tradition of the West is embodied in the Great Conversation that began in the dawn of history and that continues to the present day. Whatever the merits of other civilizations in other respects, no civilization is like that of the West in this respect.”

- Robert Maynard Hutchins, “The Great Conversation”

“The great ideas of the West—rationalism, self-criticism, the disinterested search for truth, the separation of church and state, the rule of law and equality under the law, freedom of thought and expression, human rights, and liberal democracy—are superior to any others devised by humankind.”

- Ibn Warraq in response to Tariq Ramadan, City Journal

“But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” - Matthew Arnold, Dover Beach

The Vanishing West: 1964–2010

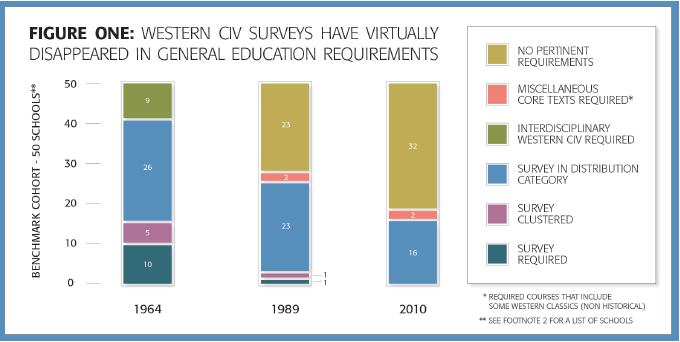

In 1964, students studying the liberal arts and sciences at the most academically competitive colleges and universities in the United States often took a two-semester sequence of courses on the history of Western Civilization. In our survey of 50 such colleges and universities, 20 percent of them required these courses. The rest of the institutions—80 percent— made students familiar with Western Civilization in some form, whether as part of general education distribution categories, Great Books surveys, or other required courses focused on cultural or intellectual history. By 2010, the picture had changed drastically at this cohort of fifty elite institutions. Courses on the history of Western Civilization are not now required at any of them, and are available in some form at only 32 percent.

Put another way, for much of the twentieth century the Western history survey course was the standard means by which colleges and universities provided American undergraduates with a coherent narrative of their civilization’s rise.1 Now, this vehicle has been abandoned with nothing equivalent put in its place. This may shock many among the general public who assume that transmitting Western Civilization’s “big picture” is a core scholastic responsibility—though much less so those academic insiders who have been paying attention to the college curriculum’s long-term devolution. But to make absolutely clear the extent of this “decline of the West,” the National Association of Scholars has undertaken a systematic examination of Western history survey offerings for the period from 1964 to 2010. This report presents our findings.

The displacement of Western Civilization from the curriculum, when noted at all, has drawn both approbation and lament. In our view, it has had negative consequences for students and for American society, but we believe the discussion is best advanced by an objective account of exactly what has happened.

The main body of our report tabulates course requirements and offerings at a large sample of leading American colleges and universities over almost half a century. But we also provide historical interpretation and analysis, with particular attention to the rise of the alternative of “world history.” After a sidelong glance at the state of American History survey requirements (a rather significant part of recent Western history), we conclude with recommendations.

Method

Our research methods were similar to those employed in several previous projects. We examined the same set of fifty leading colleges and universities whose general education programs we had analyzed in our 1996 study The Dissolution of General Education: 1914 – 1993, and for which we possessed back catalogs for the years 1964 and 1989. We used these as benchmarks in the evaluation of current requirements.2 (We refer to these universities and colleges as our “benchmark cohort”). To gain greater contemporary coverage, we added the institutions that had been designated as among U.S. News & World Report’s 62 top public universities in 2009, the last ranking that appeared before our study commenced.3 And to ensure that all fifty states would be represented by this part of the study, we also added thirteen state “flagship” universities not ranked by U.S. News & World Report in 2009. In this study we refer to these 75 institutions as our “public cohort.” We report data on them only for 2010.

The pre–2010 data were collected from the official catalogs published by the schools in our benchmark cohort. For present-day requirements, we opted to consult descriptions posted online. Official websites usually provide the most current course offerings and changes in requirements; the traditional print catalogs are slower to adjust and have actually been discontinued by some colleges and universities, which now maintain websites exclusively. Of course, some websites are more complicated than others, and the relevant information isn’t always easy to track down. The conclusions presented here reflect our best efforts to read these sources accurately. In cases where we could not interpret the catalog with assurance we contacted officials at the institutions for clarification.

The first question we asked in examining this material was whether a university or college required a Western history survey course, or courses, in order to receive a baccalaureate degree.4 (Where there wasn’t a single institution-wide requirement, we examined the requirements of the college of liberal arts and sciences). The second was whether these requirements were found in the history major.

We also sought to distinguish between survey courses that aimed in principle at a comprehensive history of the West and others that, while still offering a broad view, covered only a portion of Western history. The latter we designated “partial survey” courses. The full survey courses commenced with ancient Greece. Partial survey courses commenced variously with the Roman Republic, the appearance of Christianity, the late Roman Empire, or the early Italian Renaissance.

Finding 1

Western History Survey Courses, Commonplace Little More Than a Generation Ago and Frequently Mandated, Have Virtually Disappeared From General Education Requirements.

I. 1964 Benchmark Cohort · Western Civilization · General Education Requirements

General education history requirements have changed significantly since 1964 (see Figure 1). In that year, forty-one of the fifty schools (82 percent) included in our benchmark sample offered complete or partial Western Civilization surveys among the history courses available to undergraduates.

Ten of the schools (20 percent) in this cohort required that all liberal arts and science undergraduates take two full semesters (including Cal Tech and MIT, which did not then offer a major in history), while five (10 percent) others placed the same sequence within a small cluster of no more than six options from which liberal arts and science students were directed to make selections to fulfill their general education requirements. Another twenty-six schools (52 percent) offered some version of the survey within larger distribution categories for the same purpose (but much smaller, we note, than the distribution categories typical of the two subsequent years analyzed in our study. In 1964, the typical distribution subdivision often consisted of less than fifteen courses).

Even at the nine schools where the two-semester survey wasn’t in some way required, students were still very likely to encounter related thematic material in completing their undergraduate requirements. At Harvard, for instance, freshmen and sophomores could elect a survey of Western thought as one of four choices through which to fulfill their humanities requirement, with the three other options also focused on standard works and themes from the Western literary canon. Similarly, Columbia required all undergraduates to take a two-semester interdisciplinary survey (“Contemporary Civilization”) which examined the “major political, economic, and philosophical influences which shaped the character of Western Civilization up to the beginning of World War I.”5 At Hamilton College, a similar choice entitled “The Making of Modern Society” was available. At Wesleyan, all undergraduates were required to take a two-semester Great Books survey during their freshman year; at Bryn Mawr, students were uniformly required to take the two-semester survey, History of Philosophic Thought. Thus, while the complete or partial Western Civilization survey was not offered at each of the 50 institutions in our sample, an encounter with a significant portion of the Western historical, intellectual, literary, and cultural heritage was likely at virtually all of them.

II. 1989 Benchmark Cohort · Western Civilization · General Education Requirements

By 1989, undergraduate requirements at these institutions had changed dramatically: the Western history survey remained an absolute requirement at only one institution (2 percent), Georgetown, where a twosemester partial version covering the West and the growth of the Americas since 1500 was in place. Only one other (2 percent) still placed it within a small cluster of general education options. Another twenty-three institutions (46 percent) lumped Western history surveys together with a myriad of other courses in distribution categories generally much larger than in 1964. Those totally without a Western history sequence grew from nine in 1964 (18 percent), to twenty-five (50 percent) in 1989. Of the nine schools which in 1964 had required, instead of Western history surveys, surveys in the Western cultural heritage, intellectual history, or selected Great Books readings, only Columbia and Colgate continued to do so. Thus, at only three schools (6 percent) did the baccalaureate requirement still essentially provide the same kind of introduction to Western Civilization that had prevailed a quarter century earlier.

III. 2010 Benchmark Cohort · Western Civilization · General Education Requirements

As of 2010, none of our benchmark schools mandated the traditional two-semester Western history survey; none placed it within a cluster, and only sixteen (32 percent) put it within large distribution categories, which now sometimes included more than a hundred other courses. As they had in 1989, Columbia and Colgate (4 percent) continued to require somewhat modified versions of their undergraduate core courses devoted to the cultural or intellectual themes of the Western heritage, but including non-Western material as well. By contrast, thirty-four (68 percent) of the other schools did not even offer a complete Western Civilization survey. Individual courses devoted to various themes or segments in the Western experience were available, but only as part of the ever-expanding grab bag of distribution options from which students can rather freely choose.

Indeed, a significant number of schools no longer require any study of history. Six of those in our sample (12 percent), for instance, had no general education requirements at all (apart from a freshman writing course).

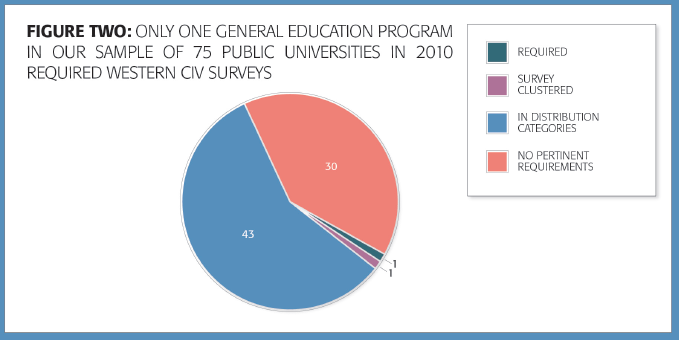

IV. 2010 Public Cohort · Western Civilization · General Education Requirements

A similar pattern prevails in the larger sample of public universities we examined (See Figure 2). Of these seventy-five institutions, only one (1.3 percent), the University of South Carolina, retained a Western history survey requirement, and there only a single semester; one other, the University of New Mexico (1.3 percent), placed it within a cluster. Forty-three (57.3 percent) of the institutions included the complete or partial survey within a broad distribution category. At thirty other institutions (40 percent), the Western history survey was not offered at all. There were only specialized courses covering limited segments of the thematic content covered by the traditional survey.

Thus, as far as general education goes, the required study of Western history nearly disappeared. Alarmingly, this also turned out to be true for students majoring in history.

Finding 2

Even for History Majors, Western Civilization Surveys Are Now Rarely Required

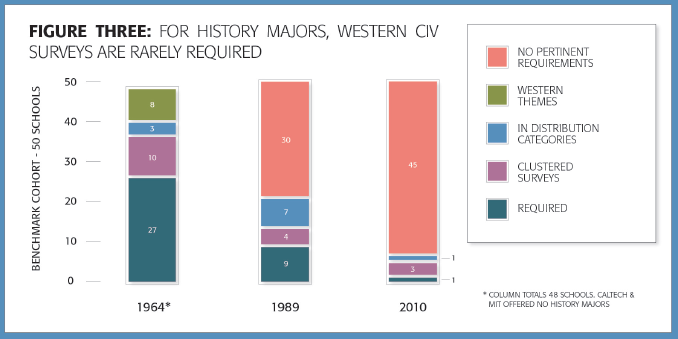

Even for undergraduate history majors—our future history teachers and professors, and many of our future lawyers, civic leaders, and public officials—the acquisition of a broad historical overview of Western Civilization is rarely a requirement.

I. 1964 Benchmark Cohort · Western Civilization · History Majors

In 1964, twenty-five of our benchmark institutions (52.1 percent) mandated a complete or partial two-semester Western history survey for history majors, either as part of a special major requirement or as part of their general education requirement. (MIT and Caltech did not offer a major in history at this time, hence the reported 1964 major percentages are based on a total of only 48 institutions) Another ten history departments (20.8 percent) placed their Western Civilization survey sequence within a small cluster of options, from which majors were required to choose. Three others (6.3 percent), included Western history within slightly larger distribution categories (See Figure 3).

Among the remaining institutions, a variety of individual program features assured that students would encounter the Western tradition in some way, if not specifically in a required two-semester history sequence. Students at Carleton were “strongly encouraged” to take the complete survey in Western history as a prerequisite for declaring their major. At Colby College, all majors were required to take a two-course survey focused on “Social Thinkers in the Western Tradition.” Similarly, all students at Grinnell College, irrespective of their major fields, were required to complete a two-semester survey covering the “Western Heritage.” Wesleyan history majors received an especially strong dose: in addition to the two-semester Great Books survey which was a uniform general education component, they were also required to complete a two-course survey devoted to the Greco-Roman heritage. One way or another then, it was highly likely that all history majors—as well as most undergraduates—would encounter the Western tradition in some capacity in 1964.

II. 1989 Benchmark Cohort · Western Civilization · History Majors

By 1989, this number had shrunk drastically, with only nine (18 percent) history departments still requiring completion of the entire or partial survey. Four (8 percent) placed it within a small cluster of courses, and seven (14 percent) included it within a distribution range generally a good deal larger than its 1964 equivalent. The thirty remaining major programs (60 percent) did not require a survey of Western Civilization in any form, and had often dropped it from their course offerings altogether.

III. 2010 Benchmark Cohort · Western Civilization · History Majors

Today, only a few programs retain a diminished remnant of the traditional survey for history majors. For example, William and Mary—whose history major seems particularly solid in comparison with other toptier schools—alone (2 percent) requires all majors to take at least one of the two semesters, the entire two-semester survey of American history, and one course of a non-Western survey sequence. Three other schools (6 percent) continue to include some version of the Western Civilization survey among a cluster of entry-level options from which history majors must choose, and one (2 percent) places it within a very broad distribution range. In none of the 45 other benchmark schools (90 percent) does the Western history survey, or any part of it, remain a specific requirement for history majors.

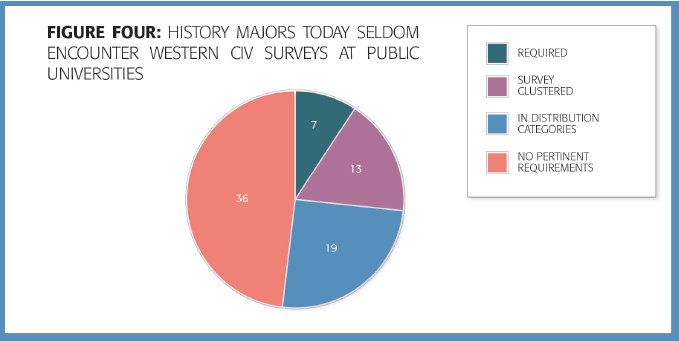

IV. 2010 Public Cohort · Western Civilization · History Majors

Of the seventy-five programs in the larger population of public universities we examined, just seven (10.7 percent), including the single school where it is a general education requirement, mandated the two course Western Civilization history sequence (See Figure 4).

Several programs in this small group seem especially noteworthy. Pennsylvania State University at College Park for instance, requires all history majors, irrespective of their particular fields of specialization, to complete the full two-term sequence of both the Western Civilization and American history surveys, plus an additional year-long sequence covering a non-Western Civilization. At the University of Ohio, majors must complete a two-course survey of American history, and can choose two courses from among a three course sequence in Western Civilization, a three-course sequence in “Western heritage,” and a two-course sequence in world history. Similarly at Texas A&M, majors must complete the two-semester US history sequence, and two semesters of either Western Civilization or world history.

But these programs are outliers. Of the remaining institutions from our public cohort, thirteen (17.3 percent) place the complete or partial survey within a cluster, and nineteen others (25.3 percent) include it within the usual broad distribution options. At the other 36 programs (48 percent), the Western history survey is not required and unavailable.

In general, the colleges and universities within our study have loose and amorphous requirements for history majors. Students are presented with a large menu of course options from which they can construct their programs to suit their individual tastes and interests. If they happen to study Western Civilization, it will depend largely on the choices of individual students at the diminishing number of schools where the subject is still available.

V. Case Study: Brown University’s Western Civilization Requirements for History Majors

The history major at Brown University is like many of its counterparts among the top-tier institutions, and many state universities as well. Majors must complete a minimum of ten courses, including at least eight within the department. Introductory survey or “gateway” courses (the ones offered vary from semester to semester) are available, although none is specifically required. Instead, as part of the department’s advisement process for its majors, students are individually directed to select surveys thematically connected to a “Field of Focus,” or specialization, such as “European,” “Asian,” or “American,” depending on their level of prior preparation.

Students at Brown must also satisfy distribution requirements, organized by geography and chronology. For the geography distribution component, for example, majors must select one course from three of six areas: Africa, East Asia, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and South Asia, and North America.

The department also requires majors to distribute course selections among “modern” and “pre-modern” periods. Students appear to have considerable latitude in selecting their field of focus. In the department’s description it may be defined geographically, chronologically, a combination of both of these, and by theme. Thematic fields can include—but are not limited to—“comparative colonialism,” “gender and sexuality,” “law and society,” “race and ethnicity,” “STEAM (science, technology, environment and medicine),” and “urban history.” Examples of transnational fields include: “The Ancient World,” “The Early Modern Atlantic World,” “Africa and the Diaspora,” “The Mediterranean World from Antiquity to the Middle Ages,” and “The Pacific World.” While there is some structure to Brown’s history major, a great deal is also left to student choice. Given such a wide range of options, it seems highly improbable that most students—except possibly those who actually concentrate in European history—will choose to organize their studies with a view to acquiring the framework demanded at Penn State and Ohio University.

Brown’s specific history course offerings also include a striking range of narrowly focused special interests for which the 1964 course offerings lacked any equivalent. To be sure, there remained in 2010 a sizable number of standard traditional courses such as “English History, 1529–1660,” “Modern Russia to the Revolution,” and “Islamic History, 1400–1800.” But students can also choose from a wide range of rather recherché offerings like “Culture and U.S. Empire,” “Academic Freedom on Trial: A Century of Campus Controversies,” and “The Border/La Frontera.”

As Brown is among those schools with no general education requirements, there is nothing else in its undergraduate curriculum that offsets the gaps in its history major.

VI. Examples from the Public Cohort of Western Civilization Requirements for History Majors

The same lack of structure can also be found in the history programs of many leading state institutions. At Indiana University, Bloomington, for instance, the history major is actually less structured than Brown’s. No introductory surveys are required—the Western Civilization survey is not even offered at present—and while the two-semester American history survey is available, it is but one option among numerous others. History majors are required to complete at least ten courses: four chosen for a concentration, another two selected as a “field” (from courses outside the concentration), a history writing seminar in both the junior and senior years, and two additional courses taken from other groups. Majors may organize their choices around categories as wide ranging as “Africa and the Middle East,” “Ancient,” “Asia,” “Europe after 1500,” “Jewish,” “Latin America,” “Medieval,” “Pre-Modern Mediterranean World,” “Russia and Eastern Europe,” “United States,” and “World and Comparative.”

There are no requirements specified within the concentration or the field, leaving students almost complete discretion among an expansive number of offerings. Presumably, students concentrating in American history may choose to take one or both of the two-semester survey courses in American history, but nothing seems to require that they do so. On the other hand, they may decide in favor of such alternatives as “American Sexual Histories,” “Gender and Sexuality in American History,” “Sex, Lies and Diaries: Untold Southern Stories,” or “Elvis, Dylan and Postwar America.” Similarly, a student with “Europe after 1500” as an area of concentration can complete the four-course requirement by choosing among offerings ranging from traditional surveys to “War and the Comics,” “The Mafia and Other Italian Mysteries,” and “British Sexual Histories.”

While individual students may choose to design their majors in a traditional fashion, there are no formal guidelines that compel them to do so. As a result, the traditional surveys or similar courses, though available, apparently carry no greater weight than the highly specialized, narrowly focused, and often idiosyncratic offerings cited above. Thus, students may elect to take a survey of twentieth-century American history, in which the nation’s participation in World War II, the defeat of Adolf Hitler, and the ensuing Cold War would be scrutinized. But if they wish, they may also elect one course devoted to the rise of Elvis Presley, or another which examines the arcane erotica confided to personal diaries in the Antebellum South. None apparently stands as more significant than another; it’s simply a matter of student choice.

Finding 3

American History Survey Requirements for History Majors Have All but Disappeared at the Top Fifty Institutions and Are Present at Only Slightly More Than 10 Percent of Leading Public Universities.

A similar pattern presents itself with respect to American history, although the decline starts from a lower plateau.

I. 1964 Benchmark Cohort · American History · History Majors

In 1964, seven (14.6 percent) of the history majors at our fifty benchmark institutions mandated a two-semester American history survey course, (five of which also required completion of an entire Western history survey). Another eleven major programs (22.9 percent) included the American history survey within a cluster. Fourteen additional programs (29.1 percent), while not specifically requiring the two-semester American history survey, directed students to take at least one course in American history, irrespective of their field of concentration. In all, thirty-two of the benchmark schools in our sample (66 percent) required that students majoring in history have some exposure to American history.6

II. 1989 Benchmark Cohort · American History · History Majors

In 1989 just one benchmark department, at the College of William and Mary, (2 percent) continued to require the full two-semester survey for history majors. UC/Berkeley’s program required that majors take at least half of the two-semester survey; five others (10 percent) placed it within a small cluster from which history majors were required to choose, and twenty-four (48 percent) mandated that at least one American history course of some kind be included, usually from a very wide range of options.

III. 2010 Benchmark Cohort · American History · History Majors

As it did in 1989, the College of William and Mary stood alone in requiring the full two semesters of American history of its departmental majors.

IV. 2010 Public Cohort · American History · History Majors

The situation among the history majors of the seventy-five leading state universities surveyed is only slightly better.7 In ten of these programs (13.3 percent), the two-semester survey in American history is required of all majors. In four others (5.3 percent), history students are required to take at least one of the two semesters of the survey. In an additional seven (9.3 percent) it is offered among a small cluster of options. Several institutions have state-mandated American history requirements within their general education requirement, though as applied this doesn’t necessarily entail taking an American history survey course or sequence.8

V. 2010: The Role of Advanced Placement Courses

A good many prospective history majors, as well as others, especially among those seeking entry into the best colleges and universities, no doubt successfully completed at least some of these courses, the American history Advanced Placement course being by far the most likely. Perhaps in the minds of some history faculties the existence of AP courses provides a justification for no longer mandating American history and Western Civilization surveys. We also acknowledge that some faculty members may advise aspiring history majors to select these or similar courses where their prior preparation is deemed insufficient. But we have no data to indicate the extent to which this occurs and, given the spottiness of many undergraduate advisement systems, don’t believe them to be a substitute for formal requirements.

Still, even apart from the question of whether or not success in an AP course taught by a talented high school teacher is the equivalent of a course taught by college-level faculty, and the fact that no AP course covers the full sweep of what used to be part of the standard Western Civilization sequence, it remains that none of the departmental requirements we examined included a prescription that the Western Civilization or the American history surveys be taken in the absence of successful AP completion. (Of course in many of these departments this would not have been possible, as no such surveys were offered.) This tell-tale omission strengthens our view that providing students with a broad view of their civilization’s development is no longer a disciplinary priority.

Finding 4

Surveys of American History Have Not Been Included in General Education Requirements in the Last Half-Century Among the Institutions We Studied.

None of our benchmark cohort currently makes American history an absolute general education requirement. Nor did any of them do so in 1964 or 1989. And although UCLA and UC Berkeley fall under a statutory requirement to teach American History and Institutions, students can easily fulfill this requirement by testing out or by selecting one of a wide variety of highly specialized courses.

Finding 5

World History Has Become a Far More Common Course Than It Once Was, Though It Is Seldom Either a General Education Requirement or Requirement for History Majors.

We also reviewed course catalogs in search of cases where “World History” (or variants such as “World Civilization”) is either offered or required.

In 2010 two of our benchmark institutions “clustered” world history surveys for majors, and one included it as a general education distribution option, among a very wide selection of other courses. At the seventyfive universities in our public cohort, sixteen (21.3 percent) now place a world history survey somewhere within their general education requirements. Of these five (6.7 percent) actually require a world history course of all students: the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, the University of California/Riverside, the University of Buffalo/ SUNY, and Washington State University at Pullman. Another university (Auburn) puts world history as an option within a small cluster. Ten (13.3 percent) include it as part of a broad distribution category.

Similarly, five universities in the public cohort require world history for history majors (i.e., the same institutions that require it across the board), nine (12 percent) “cluster” it for majors, and one puts it in a larger distribution category for majors (with an additional department recommending it for majors).

World history is now viewed by many as a substitute for Western history, especially at the high school level. The controversy dates back at least to 1994, when, as Peter Stearns described it, “a commission of historians designated to define secondary school standards in history issued a thick book on goals in world history.”9 But the shift to world history is affecting colleges as well, with our data suggesting that public universities are more receptive to it than elite institutions.

Apart from course offerings there are other tell-tale signs of change. World history doctoral programs, for example, are becoming more common. The website of the World History Association currently lists twenty-six of them.10 The American Historical Association’s 2001–02 survey of history departments found more departments in master and doctoral degree-awarding institutions having world history specialists than Western Civilization specialists (with regional specialties, including European history, classified as additional possibilities). Indeed, in a subsequent 2010 AHA survey, “Western Civilization” was no longer listed as a distinct field—although world history was.11 (At the baccalaureate level, institutions still report slightly more Western Civilization than world history specialists.)12 The same pattern shows up with respect to Advanced Placement exams. According to the College Board, in 2009, 98,981 students took the World History AP exam while a smaller number, 78,276, opted for the European history test—the closest thing to a Western history exam, covering 1450 to the present, but not the Greco-Roman and Medieval periods.13

There is thus some evidence then that world history is in the process of superseding Western history as the preferred non-American history survey course, and even as a scholarly specialization.14

Interpretation

Over the last half century (our survey covers a 46–year span) American higher education has largely abandoned its narration of Western Civilization’s story. This abandonment was, of course, part of a larger pattern of curricular disintegration we traced in our 1996 report, The Dissolution of General Education 1914–1993. But it has also had its own distinct development.

Western Civilization courses had deep symbolic importance for those who were seeking to refocus the undergraduate curriculum on multiculturalism and diversity. When in 1987 Jesse Jackson led Stanford protestors in a chant of “Hey hey, ho ho, Western Culture’s got to go,” the object was not to displace mathematics or English literature, but eliminate a course that focused on Western Civilization. The disappearance of Western Civilization courses thus reflected, at least in part and at least at first, less a pedagogical reassessment of how the curriculum should be shaped than an ideological hostility to a subject. “Western Civilization” had come to be seen as a form of apologetics for racism, imperialism, sexism, and colonialism. Demoting it from a requirement or eliminating it altogether, could therefore be viewed as a blow against these oppressions.

The decline of Western Civilization courses, however, left a curricular vacuum. These courses once stood not just as a foundation for history majors but as something of a framework for the entirety of liberal arts education. The study of science, politics, philosophy, literature, and the arts made sense—or at least more sense—as part of the narrative of a civilization’s rise and development. Absent that narrative, the typical college curriculum became more entropic and unfocused. The dissolution of general education, already underway in the early 1960s, was accelerated by the abandonment of Western Civilization courses.

Nothing has really taken the place of Western Civilization, although a variety of encompassing ideas have been offered: multiculturalism (or diversity, inclusivity, etc.), world history, and most recently sustainability.15 In this report we have examined, albeit briefly, only one of these—world history. But it seems clear that none of these alternative heuristics really works as a comprehensive organizing principle for higher education the way Western Civilization once did.

In the absence of such an organizing principle the curriculum spins out into an all-things-to-all-people cornucopia of offerings, many of them exceptionally narrow in scope and many of them trivial in character. Lawrence Mead has described this florescence of marginalia and trifles as a new “scholasticism,” and our findings strongly support his insight.16

Survey courses are available at many universities for those who want them, but it is clear that they now occupy a fairly low rung on the pedagogical ladder. One index of this low rank is that, in the reduced number of universities that still offer such courses, they are often taught by lecturers or other junior faculty members. Our study documents not just the decline of a particular undergraduate course but the attenuation of a long-held vision of what it means to be an educated person.

Western Civilization vs. World History?

One way of reflecting on this report is to consider the appearance of world history in undergraduate curricula. To be sure, world history does not enjoy anything like the status once conferred on Western Civilization—general education has become too attenuated for this honor to be conferred on much of anything—but it does have vigorous champions and seems to be gaining ground, at least at some public universities.

We don’t wish to overstate this development, but we do see it as an opportunity for a potentially fruitful contrast. Moreover, even if world history is unlikely to become anything like an across-the-board undergraduate requirement, it captures some of the spirit of the contemporary university that is also expressed in diffuse emphasis on concepts such as globalization, world citizenship, and even sustainability (which is frequently put forward as a mandate for post-national institutions and a focus on the non-Western world).

In that light, we see room for developing three arguments. First, globalization is a genuine phenomenon fully worthy of study, but to study it effectively, students need to know about Western Civilization. That’s because to a very high degree the globalized world is one that has been shaped by Western Civilization. Without the West’s advances in communications and transportation, any form of global civilization would be impossible. Studying the history of the West brings a student to grips, as nothing else can, with the roots, the shaping events, the underlying causes of the process and substance of globalization, indeed, of the creation of modernity itself.

Second, Western Civilization has transformed the human condition. This remains invisible or at best gropingly understood by students who have had no chance to study systematically the rise of the West, which brings into focus better than anything else the origins and development of a sophisticated worldwide marketplace; an impersonal, rule-based bureaucracy; the scientific outlook; modern medicine, lengthened life-spans, democracy and constitutionalism, and the massive increase in material abundance.

Third, America is part of Western Civilization. We thus cannot understand ourselves except against the background of Western Civilization, and at this point in history, we cannot understand Western Civilization without grasping America’s particular additions to it. The United States is one of the great theaters in which the West’s recent history has unfolded. Most American university students are Americans and ought to have the chance to learn of the origins of their culture and country.

We recognize that none of these points is likely to be taken as self-evident in the contemporary academy. They are, in a word, debatable. But where is the debate? Without some kind of restoration of the study of Western Civilization and American history, the advocates of world history, globalization, multiculturalism, sustainability, etc. are doomed to incoherence. Their arguments are in fact derivative from and deeply dependent on knowledge of the Western experience. As the curricular focus on Western Civilization fades away, all the proponents of these new approaches will be left with is mere caricature of the past they hope to transcend and no roadmaps for the future.

Why Study Western Civilization?

Globalization and world history rightly understood provide new reasons for restoring a focus on Western Civilization, but these aren’t the only reasons to bring back the subject. Western Civilization is worth studying in its own right for its unique pattern of creativity. This argument has been made perhaps most forcefully in recent scholarship by the Canadian historical sociologist Ricardo Duchesne.17

The academic disciplines that we work with, including the individual sciences, are almost all Western creations. Many of humanity’s highest achievements in philosophy, engineering, and the arts are Western. The study of Western history can hardly proceed without coming to terms with its catalog of disastrous decisions and great follies too, but the abiding reason to study the West is that the West continues to matter.18

It has shaped and continues to shape the world politically, economically, intellectually, legally, and aesthetically. The worst tyrannies of our time, even in the non-Western world, are typically rooted in Western ideas. Think of Mao’s, Kim Il-Sung’s, and Pol Pot’s appropriation of Marxism, and the Arab Baathist movement founded by Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Bitar in emulation of Robespierre and the Jacobin and Fascist conceptions of national unity. This is not to limit the case for studying the history of the West to the argument that it is a key to understanding “the Rest,” but to say that the West is a powerful and complex phenomenon that demands elucidation. Students who are left with scant knowledge of Western Civilization are ill-equipped to make sense of their own lives or the world around them.

The Way Forward

History education is a core civic responsibility and needs far more emphasis than it is presently receiving. We welcome history curricula that give students the opportunity to learn about Asia, Africa, Latin America, the various diasporas, and the interconnections, ancient and modern, of the world’s peoples. We believe that the ambitious embrace of human history, however, is best grounded in knowledge of the singular achievements of the West. This may imply a comparative framework: the West in contrast to one or a number of other high civilizations? But students need to begin somewhere, and it makes considerably greater sense in our view that they begin by acquiring knowledge of the civilization of which they are part. (By virtue of their studying in a Western university they are of course part of Western Civilization regardless of their individual backgrounds.)

A good Western history survey sequence distinguishes the features that eventually led to the West’s expansion to world dominance and the West’s unique creativity. Such a survey also traces important external influences on Western development. This is not the approach typical of today’s world history courses which too often single out the West only to make it the embodiment of conquest, enslavement, oppression, social injustice, and similarly deplorable characteristics.19

Students can still get a good education in the contemporary university if they choose intelligently among the many elective courses on offer. But few undergraduates arrive armed with the judgment necessary to make these choices wisely—precisely why general education and history major programs long insisted that students master basic core requirements before they could advance to more specialized study, and particularly why they gave to learning the fundamentals of Western history so prominent a place.

Of course, the problem goes beyond the multicultural Zeitgeist. Much of the reason for the decline of the Western history survey lies in the structure of the contemporary history profession, which like most other academic fields has come to reward scholarship far more than teaching. As a result most members of college history faculties seeking career advancement will do so through research and publication, endeavors that inevitably reward specialization over breadth, and encourage instruction geared to constricted research agendas rather than the learning needs of undergraduates. This is one of the driving forces behind the loose, specialty-inclined history majors that have become the norm, and the concomitant disinclination to require survey courses of any sort, including not only Western and world history surveys, but those in American history too.

Ensuring a citizenry genuinely literate about the past thus entails recapturing and rewarding a more traditional sense of history scholarship’s professional mission, one that, at most institutions at least, restores the primacy of teaching over research, prefers the transmission of core content to ever deeper plunges into exotica, and concentrates on attempting to explain to students how the world they inhabit became the place it is. This means, in turn, that the history profession must reconsider its fundamental responsibilities for preserving our civic culture and the store of historical memory about our civilization (and nation) that underlies it.

Recommendations

Having charted a decline that stretches over several decades, we recognize that the odds are against any sudden restoration of Western Civilization as a linchpin of the American college curriculum. Weighing against this possibility is the drift of American culture, the temper of the university, the convenience of faculty members accustomed to the current system, and the dearth of qualified teachers. Repairing a broken tradition is a difficult task under the best circumstances, and circumstances in which numerous parties have a vested interest in keeping it broken is even more daunting. That said, we are not without hope. Contemporary American higher education is in profound trouble. Its expenses are running out of control and its prices are escalating at exactly the time when the public is growing more and more skeptical of the quality of academic programs and the practical value of the college degree. In addition, new forms of competition are arising that are convincing many who would have once attended college to go elsewhere. Faculty unions are alarmed at the prospect of losing students to online for-profit institutions that offer stripped-down curricula. State legislatures are scrutinizing the budgets of public universities and in many cases imposing steep cuts.

In this situation, college presidents, trustees, and others in a position of influence have a strong motive to reevaluate the priorities of their institutions. The something-for-everyone university and the model of mass higher education marketed to the lowest common denominator looks unsustainable. What are the alternatives?

We think one alternative that should be actively weighed is the “value proposition” of a college curriculum that is centered once again on Western Civilization. Indeed, we suspect that many supporters of universities—trustees, alumni, foundations, and individual benefactors—wrongly suppose that Western Civilization remains integral to the undergraduate curriculum. We further suspect that college presidents are in no particular hurry to disabuse them of this illusion and may in some cases themselves be unaware of the extent to which students in their academic programs are steered around and away from any knowledge of their own civilization’s history. Our first set of recommendations therefore push toward making the problem manifest. These recommendations apply to all colleges and universities, not just the two cohorts we examined in this report.

I. Recommendation: Study the Problem.

Colleges and universities should examine their curricula to determine the extent to which Western Civilization is present as a coherent object of study in their institutions. Other stakeholders should raise the pertinent questions, especially if colleges and universities fail to.

Our report has traced the decline of a particular course as a prominent marker of the de-emphasis of Western Civilization, but the problem has other dimensions that are beyond the scope of this report and need to be examined in the context of each particular college’s curriculum.20 Courses that are sometimes put forward as dealing with Western Civilization may, in fact, be something else, e.g. exercises in multicultural polemic or postmodern deconstruction. The central question is whether undergraduate students have an opportunity to gain a broad, reasonably detailed, and integrative understanding of the Western tradition.

Under this broad recommendation, we offer ten specific proposals aimed at raising the pertinent questions in venues starting with the college president, trustees, alumni and donors, then extending outward to other civic and political authorities. College presidents should take up this issue, but it seems to us more likely that external bodies will take the initiative. With that in mind, we offer this as a list of prompts to those who are in a position to begin the conversation.

A. Every college president should appoint a commission to examine the current place of Western Civilization in his undergraduate curriculum.

B. College trustees should carefully prepare appropriate questions to ask college officials on this subject. Alternatively, we recommend that college boards of trustees ask their presidents for a full, systematic report on how Western Civilization and American history are taught within their institutions.

C. Alumni of American colleges and universities should inquire of their alma maters what current policies are for requiring the study of Western Civilization and American history. They should emphasize that such policies are matters of importance to them.

D. The organizations representing colleges and universities collectively—such as the Association of American Colleges and Universities, the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, and the American Association of State Colleges and Universities—should devote deliberate attention to the place of Western Civilization and American history in their ongoing efforts to raise academic standards.

E. The American Historical Association, the Organization of American Historians, and the Historical Society should commence open-minded reviews of undergraduate curricular standards in the United States, with attention as to how adequate the presentation of Western Civilization is, both to history majors and the general student population.

F. Accrediting associations should pay explicit attention to the place of Western Civilization and American history in the undergraduate curriculum. If these are missing, then curricula should be revised to include them.

G. Governors should appoint advisory commissions to examine the place of Western Civilization and American history requirements at public colleges and universities. These commissions should seek and examine model Western Civilization curricula.

H. State legislatures should hold public hearings on the teaching of Western Civilization and American history at public colleges and universities.

I. Foundations supporting the humanities and social sciences in higher education should emphasize to their beneficiaries the importance of the undergraduate study of Western Civilization and American history.

J. The National Endowment for the Humanities should promote the study of Western Civilization by targeting grants to scholars working on ways to improve research, scholarship, college instruction, and public understanding in this area.

K. Congress should fund the already authorized “American History for Freedom Program,” which can provide grants to college and university Western Civilization programs.

II. Recommendation: Fix the Curriculum.

Colleges and universities should adopt curricular requirements that include Western Civilization as a discrete topic of study. This will require a variety of program modifications.

A. Undergraduate general education requirements should include a Western Civilization requirement. It should cover the Greco-Roman world and Western history up to 1500 as well as the subsequent modern period.

B. The syllabus for Western Civilization needs to be reinvented. We are not calling for a return to the way the course was taught fifty years ago. Teaching Western Civilization today would require synthesizing new scholarship and taking into account the themes of globalization and the claims of “world history.” A new Western Civilization sequence needs a new syllabus. (We attach as an appendix to this report, with the permission of its author, an example of a traditional Western Civilization syllabus for a course currently taught at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.)

C. Western Civilization survey courses should be a prerequisite for upper level courses in many liberal arts fields, including philosophy, art history, political science, sociology, anthropology, literature, and economics. Of course, a general education requirement in Western Civilization would obviate the need for this.

D. History majors, whatever their specialized fields, should be required to complete at least a two-semester survey course in the history of Western Civilization.

E. Incoming freshmen should be provided with a recommended reading list that includes at least one single-volume synthesis of the history of Western Civilization.

F. Colleges and universities should take steps to ensure that students do not place out of Western Civilization requirements without substantial proof of mastery of this area. We recommend that no score less than a 5 on the AP European history exam be accepted as adequate. And because the AP exam does not cover the Greco-Roman world or the West before 1450, students who do not place out should be required to take a survey course in that period.

G. Students transferring into a college should be held to a strict standard for receiving credit in the area of Western Civilization.

III. Recommendation: Repair the Pipeline.

We need professors of history who are competent to teach basic Western Civilization courses. The flow of new Ph.D.s with the requisite knowledge and skills appears to have been reduced to a trickle. Fixing the problem will require both changes in how graduate schools prepare doctoral students and how colleges and universities hire historians.

A. Graduate history programs should ensure that individuals receiving doctorates have demonstrated competence in Western Civilization regardless of their specializations.

B. Universities with graduate programs in history need to ensure that all candidates for a Ph.D. in history be qualified to teach a two-semester Western Civilization survey course.

C. In hiring specialists in any area of history, college and university history departments should take care to ensure that all candidates to whom offers are made possess competence in the history of Western Civilization.

D. History departments should make it a policy that all their members teach Western Civilization survey courses from time to time. It is especially important for senior members of history departments to continue to teach these courses both to communicate the seriousness of the subject, model the course for junior faculty members, and maintain the breadth of their own intellectual horizons.

E. More emphasis should be given to teaching in graduate training, and as a criterion of professional evaluation in those institutions whose central mission is undergraduate instruction. Survey courses and education in breadth can only flourish where teaching is an honored and rewarded calling.

1We have capitalized “Western Civilization” throughout this report as both the title of a course and a field of study.

2The institutions examined in The Dissolution of General Education, 1914–1996, were: Amherst College, Barnard College, Bates College, Bowdoin College, Brown University, Bryn Mawr College, California Institute of Technology, Carleton College, Colby College, Colgate University, College of William & Mary, Columbia University, Cornell University, Dartmouth College, Davidson College, Duke University, Georgetown University, Grinnell College, Hamilton College, Harvard University, Haverford College, Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Middlebury College, Mount Holyoke College, Northwestern University, Oberlin College, Pomona College, Princeton University, Rice University, Smith College, Stanford University, Swarthmore College, Trinity College of Hartford, CT, University of California at Berkeley, University of California at Los Angeles, University of Chicago, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of Notre Dame, University of Pennsylvania, University of Virginia, Vanderbilt University, Vassar College, Washington & Lee University, Washington University in St. Louis, Wellesley College, Wesleyan University, Williams College, and Yale University. The institutions examined in our “public cohort” for 2010 include: Arizona State University, Auburn University, Clemson University, Colorado School of Mines, Colorado State University, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Georgia Institute of Technology, Indiana University, Bloomington, Iowa State University, Louisiana State University, Miami University of Ohio, Oxford, Michigan State University, Michigan Technological University, Missouri University of Science and Technology, New Jersey Institute of Technology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, Ohio State University, Ohio University, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Purdue University, Rhode Island University, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, SUNY Buffalo, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, SUNY, Binghamton, SUNY Stony Brook, Texas A&M University, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, University of Alaska, University of Arizona, Tucson, University of Arkansas, University of California, San Diego, University of California, Davis, University of California, Irvine, University of California, Riverside, University of California, Santa Barbara, University of California, Santa Cruz, University of Colorado, Boulder, University of Connecticut, Storrs, University of Delaware, University of Florida, Gainesville, University of Georgia, University of Hawaii, University of Idaho, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, University of Iowa, University of Kansas, University of Kentucky, University of Maine, University of Maryland, College Park, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, University of Mississippi, University of Missouri, University of Montana, University of Nevada, University of New Hampshire, University of New Mexico, University of North Dakota, University of Oklahoma, Norman, University of Oregon, University of Pittsburgh, University of South Carolina, Columbia, University of South Dakota, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, University of Texas, Austin, University of Utah, University of Vermont, University of Washington, Seattle, University of Wisconsin, Madison, University of Wyoming, Virginia Tech, Washington State University, West Virginia University.

3The U.S. News & World Report list actually included 66 institutions. We used 62 of them because the other four overlapped with our list of top fifty institutions.

4We counted as a “Western history survey sequence” any two-semester (or three-quarter) sequence which covered Western history from Greco-Roman times to the twentieth century, regardless of the title of the course. We note, but did not in our tabulation count, courses that focused primarily on literary or philosophical works or “great books” courses. Thus, for example, Columbia University’s famous required “Contemporary Civilization” course is not, in this report, considered a Western history survey.

5 Columbia College Bulletin, 1964-65, p.67 As noted, roughly similar requirements were in place at the other four schools where a Western history survey was not mandatory. At Bates College, all students completed a four-semester core sequence, “Cultural Heritage.” Colby College required “Social Thinkers in the Western Tradition” of history majors, and included the sequence as part of a small distribution option for all other students. At Colgate University, all undergraduates completed a seven-course core which examined the West’s cultural, historical, literary and philosophical heritage. Grinnell students uniformly took a two-semester, interdisciplinary sequence, “Western Heritage.”

6 Other departments, we suspect, may well have shared Princeton’s expectation that prospective history majors had “acquired an elementary knowledge of the main facts of European and American history.” Moreover, American history together with Western European history, was a required field, in each of which Princeton’s history majors were required to take a comprehensive departmental exam at the end of their senior years. It was thus assured that history majors would have studied the American narrative in some depth as part of their major programs, irrespective of their individual pursuits.

7 Our data here reflect only present dimensions of the history major, since we did not have access to catalogs of earlier years for the 75 schools in this group.

8 The public institutions of three states—Arkansas, California, and Texas—are required by statute to include an American history component in their undergraduate requirements. This does not, however, guarantee that students will actually take the traditional American history survey. At the University of Texas, for example, such a survey is indeed available to fulfill the two-course requirement in American history, but students may also elect such alternatives as “The Civil War in Fiction, Fact and Film,” “America and the Holocaust,” or “U.S. Women’s Sexuality and Gender to 1865.” These may be academically worthy courses, but students who use them to complete the American history requirement will not learn a great deal about the Constitution or any of the signal events in the American past. A similar set of options also exists at many other California institutions, including one allowing students to test out of the requirement and thus avoid studying American history at the college level altogether. Only at the University of Arkansas did we find an undergraduate core curriculum in which one course in American history or the American constitutional system was uniformly required of all degree candidates, with no exceptions or options through which students could effectively avoid the deeper study of American history.

9 Peter Stearns, “World History: Curriculum and Controversy,” AP Central, 2006

10 Ane Lindvedt, The World History Association lists twenty-six “world history doctoral programs” in the U.S.

11 Robert B. Townsend, “A Profile of the History Profession, 2010,” Perspectives, American Historical Association, October, 2010. European history remained as a specialty.

12 Ibid.

13 College Board, Sixth Annual Report to the Nation, February 10, 2010. No data were given with respect to the number of students who might have taken more than one. With a score of three or better considered by most colleges to be a passing grade— the more selective schools look for fours and fives—the mean scores for takers of each of these exams in 2009 were 2.64, and 2.92.

14 Ane Lintvedt, “The Demographics of World History in the United States,” World History Connected, 1.1 (2003) http://worldhistoryconnected.press.illinois.edu/1.1/lintvedt.html. Ricardo Duchesne, “The World Without Us,” Academic Questions, 22.2 (Spring 2009), https://springerlink3.metapress.com/content/03u660pm1624w901/resource-secured/?target=fulltext.pdf&sid=jyio3p45kljx35u31ihudpvb&sh=www.springerlink.com.

15 “Sustainability” may not yet register with some readers as a curricular rubric in the same way as multiculturalism and world history. It is indeed a new addition to this contest. As of this writing, 677 college and university presidents have signed the “American College & University Presidents’ Climate Commitment,” which entails “integrating sustainability into their curriculum.” The advocates of this movement view “sustainability” as more than an approach to environmental policy. They see it as a vision that encompasses economic and social policies, personal behavior, and intellectual endeavors of all types. Numerous colleges have adopted a procedure of “sustainability audits” that require all faculty members to present annual reports on how their courses advance the sustainability agenda. See the National Association of Scholars special report on sustainability in Academic Questions, 23.1 (Spring 2010).

16 Lawrence M. Mead, “The Other Danger….Scholasticism in Academic Research,” Academic Questions, 23.4 (Winter 2010): 404–419.

17 Ricardo Duchesne, The Uniqueness of Western Civilization (Boston: Brill, 2011).

18 We recognize that some scholars draw the lines a little differently. The anthropologist Jack Goody, for example, argues that “Eurasia” is a more compelling unit of study than the West per se. We would be open to courses that explored approaches such as this. See Jack Goody, The Eurasian Miracle (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2010).

19 See College Board, World History, http://www.collegeboard.com/student/testing/ap/sub_worldhist.html. For a description of the “leveling tendencies” of many contemporary world history texts, except insofar as they stoop to denigrate the West, see Duchesne, op cit, 138–176.

20 For example, Thomas Klingenstein recently observed of Bowdoin College that it has a number of courses under the rubric of American history but not a single course on American history per se. “There are any number of courses that deal with some group aspect of America, but virtually none that deals with America as a whole. For example, there is African-American history from 1619 to 1865 and from 1865 to the present, but there is not a comparable sequence on America. Every course is social or cultural history that looks at the world through the prism of race, class, and gender. Even a course on the environment ‘examines the links between ecology and race, class, and gender.’ Do Bowdoin alumni know their alma mater offers not one history course in American political, military, diplomatic, constitutional, or intellectual history, and nothing at all on the American Founding or the Constitution; that the one Civil War course is essentially African-American history; and that there are more courses on gay and lesbian subjects than on American history?” Thomas D. Klingenstein, “A Golf Story,” Claremont Review of Books, 11.1 and 2 (winter/spring 2010/11).