PREFACE

I gave David Randall a hard time as he searched for a title to this report. We went through more than a dozen possibilities, starting with the impossibly bland Public Account. But when he came up with his nod to T. S. Eliot’s 1922 poem, the stars came out. The U.S. Department of Education is the Waste Land, in all its fractured incoherence as well as its profligacy. Readers of literature will recall that the poem itself was such a baggy monster that Eliot’s friend Ezra Pound had to delete whole sections of it to make it even minimally readable. Would that we could do the same to the actual Department of Education.

We can’t. But perhaps the Trump administration and the 119th U.S. Congress can. Waste Land, we hope, will assist in that effort.

It is doubtful that any living person really comprehends the whole of the Department of Education (ED). Since it was created in the waning days of the Carter administration and began to take form in the opening months of the Reagan administration, ED has grown like mold on the walls of a flood-ravaged house. Seemingly every session of Congress has added new tasks to ED’s mandate without ever removing the old ones and without ever asking whether these tasks are truly valuable or, if so, whether they could be accomplished in some simpler way. Some of the luggage loaded onto ED has fallen off over the years, not because of a sudden desire for efficiency, but usually because some newer and even more cumbersome bureaucratic folly has shoved it aside.

In drafting this report, we set out as innocent outsiders with the question, “What does the Department of Education actually do?” We also wondered, “How do ED’s initiatives effect ordinary schools and the students who attend those schools?” To answer the former question, we dove into published records. To answer the latter, we sent our researchers into public schools in urban Philadelphia, suburban Virginia, and rural Ohio. And then we tried to distill our findings into a readable report.

How readable it is really is for the reader to decide, but we provide a careful map of the territory in the opening section, a tight list of recommendations at the end, and an index to help the readers who are looking for particular trees in the forest.

I have no wish to make this long study yet longer, but it will help set the tone if I draw from the work of another organization that, like NAS, pokes into dark places in government bureaucracy. I refer to Open the Books, which recently documented the case of Kelisa Wing, former diversity, equity, and inclusion chief at the Department of Defense Education Activity. Ms. Wing has a history of “racially inflammatory statements,” which prompted a congressional investigation over “radical gender ideology” in Defense Department classrooms, as well as a decision by the Biden administration to close her department.1

What happened to Ms. Wing? She carried her Defense Department expertise over to the Department of Education, where she was hired at an even steeper six-figure salary. Open the Books also reports that, in 2024 in her new job at ED, she gave a conference talk on “The Backlash against Equity.”

This is but a molecule in the sea of contempt with which ED treats the educational values of the American people. That contempt, displayed in a thousand other ways, has fueled the widespread calls to abolish the Department of Education.

In this report, the National Association of Scholars does not join those calls. Rather, we have looked for ways to cut ED down to size by relocating some of its operations to other cabinet departments that we judge less likely to indulge in waste and bureaucratic sprawl. We also call for extinguishing some particular programs and reorganizing others.

This is not to say that we think closing ED is entirely a bad idea, but that it seems to us impractical at least in the near term. Much of its size is due to decades of Congress heaping more and more responsibility on it, funding it extravagantly, and fostering the public impression that it is the font of all sorts of valuable educational innovations. Think of ED as a gigantic iceberg. A frozen Waste Land. It cannot be torpedoed. It can never sink.

But it can indeed be made to melt. This report points to where the heat should be directed.

INTRODUCTION

The United States Department of Education, commonly referred to as the Education Department (ED), is too large and complex to perform its own core functions properly. In 2024, it demonstrated that it could not even distribute financial aid to college students properly.

In 2020, Congress enacted the FAFSA Simplification Act in order to simplify the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) application process, protect “the amount of income shielded from a formula used to determine aid eligibility,” and expand the number of Pell Grant recipients.2 These reforms were intended to increase the number of students who applied for and received federal student aid. ED suffered difficulties as it implemented this overhaul. Congress granted it an extension—but when ED unveiled its new rushed-to-production FAFSA system just before New Year’s Eve in 2023, it was terribly broken. Department officials had not done their due diligence in technical reviews or beta testing.

FAFSA applicants immediately discovered the new system’s serious glitches. Applicants born in the year 2000 were simply blocked from completing their application. Government Accountability Office (GAO) investigators stated that students were neither warned of this issue nor told when it was fixed. In other cases, graduate students were repeatedly informed that they were eligible for Pell Grants, even though those grants are reserved for undergraduate students. As of September 2024, the electronic signatures of applicants or their parents still would simply disappear from their signed forms, making those forms invalid. ED, moreover, seldom picked up the phone to help students, and then it failed to communicate with students about changes to their eligibility. GAO investigators stated that approximately 5.4 million calls were placed to the Department’s FAFSA help center, out of which about 4 million went unanswered. 500,000 applicants whose eligibility was altered due to other mistakes made by the Department were never notified of these changes.3

Richard Cordray, Chief Operating Officer of Federal Student Aid, resigned in Spring 2024. But Cordray was not entirely to blame. ED’s labyrinthine complexity makes it impossible for the Department to perform well any of its multitudinous tasks. ED is a jack of too many trades and a master of none. It cannot be relied on any longer even to disburse college aid properly—and in the 2024 Annualized Continuing Resolution (2024 Annualized CR), the majority of ED funds were devoted to college aid. ED disburses $106 billion in federal student loans, $29 billion in Pell Grants, and about $51 billion for everything else. ED ought to be able to perform its most important fiscal function—and it is not.

It is bad enough that ED cannot do its own job. It is worse that the Department is too large and too tangled to be held accountable when it fails.

ED is too large and complex for the public to know precisely what it does. Even policymakers tasked with its oversight face formidable barriers in executing that task, when they must discover what hundreds of separate programs do, as well as the effects of hundreds or thousands of regulations. ED’s size and complexity, and its consequent lack of transparency, make it far too immune to accountability to the public and to policymakers.

What ED actually does with its powers has mixed effects. Most of what ED does centers on disbursing money. Its four largest responsibilities, which consist of the vast majority of the funds it handles, are:

- Title I funds for disadvantaged K–12 students, disbursed by complex formula grants to local educational agencies (LEAs)4 and states (2024 Annualized CR: ca. $18 billion);

- Special education funds for physically and mentally handicapped students, disbursed by different formula grants to the states (2024 Annualized CR: ca. $14 billion);

- Pell Grants for disadvantaged postsecondary students, disbursed directly to individual students, for use at eligible postsecondary institutions (2024 Annualized CR: ca. $29 billion); and

- Direct student loans to postsecondary students, disbursed directly to individual students, for use at eligible postsecondary institutions (2024 Annualized CR: ca. $106 billion).

The federal government as a whole, largely through ED, contributes about 11% of elementary and secondary education revenues and at least 14% of higher education revenues. The last number understates the importance of federal contributions to higher education revenue, since federal assistance also leads students to contribute their own resources to their tuition. Postsecondary institutions defer to federal power with an eye both to direct federal contributions and to the entire tuition provided by every student who receives federal support.

We shall discuss in greater detail below how activist bureaucrats and policymakers use ED’s regulatory labyrinth to weaponize these funds and transform the now-dependent states and LEAs into tools of progressive activism. But these funds—as originally intended by Congress, and still to a considerable extent in practice—were meant to fund states, LEAs, postsecondary students, and postsecondary institutions as they made their own decisions about how to use them. To the extent that ED simply channels money to Americans, who then can make their own more local decisions about how to use those funds, ED funds can serve good purposes. To the extent that states and LEAs can ignore ED’s directives to impose progressive politics, ED funds may still be used as they originally were intended.

We use the phrase to the extent—and, alas, that extent has been diminishing steadily. ED adds to these funding streams an ever-growing number of grant programs that, overall, divert taxpayer money either to no effect or to impose progressive political goals. While these programs only add some tens of billions annually to ED expenditures, ED also holds its larger disbursements hostage to compliance with its regulations and its lawsuits. Above all, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) has steadily redefined the nature of Title IX and civil rights law, so that states and LEAs must either impose progressive political goals and create bureaucracies to implement them or be found to have violated Title IX or civil rights law.

The largest ED/OCR categories of abusive political imposition are:

- Informal race and sex quotas;

- Disparate impact theory, especially as applied to race and sex;

- The textually unwarranted expansion of the scope of antidiscrimination law to include (sexual) harassment, sexual orientation, gender expression, and gender identity; and

- Corollary abrogations of liberty (due process, free speech, and religious freedom).

ED and OCR bureaucrats and policymakers have frequently sidestepped the accountability mechanisms of the Office for Civil Rights—above all by means of Dear Colleague Letters (DCLs) and “voluntary” case resolutions, which are entered into by states and LEAs that wish to avoid the process-as-punishment of an OCR investigation.

ED’s means lend themselves to patchwork effects. The federal government may issue regulations, but states and LEAs can comply with more or less alacrity. The alacrity has become greater as ED pressure and financial concerns generate parallel bureaucracies in the states and LEAs, bureaucracies devoted to enforcing collaboration with federal dictates. Nevertheless, states and LEAs can imitate the old adage of the Spanish Empire, where central authority had limited ability to oversee far-flung dominions: obedezco pero no cumplo; I obey, but I do not comply.

When states and LEAs do comply, it is because ED regulations have given license to some local individual to initiate a lawsuit or an administrative complaint against the state or LEA for its alleged violation of civil rights. ED imposes its progressive agenda piecemeal, by a host of individual lawsuits, complaints, and case resolutions. Alternately, fuzzily worded DCLs, and the clear hint of case resolutions, intimidate states and LEAs to take a variety of “voluntary” actions that they believe will bring them into compliance with ED mandates. ED imposes its progressive agenda by means of a range of local actions that are never uniform, and never universal, but that are ultimately sufficient to change the nature of American education.

ED activist bureaucrats and policymakers have done a great deal to turn ED into an unaccountable and arbitrary vessel for progressive political goals. The very structure of ED, which makes states, LEAs, and postsecondary institutions financially dependent upon the federal government, tends to degrade the localized structure of American politics and society and replace it with centralized and counterproductive control by the federal government. Yet we cannot say that ED has been completely counterproductive—and our case studies and our audit below have not provided evidence to substantiate such a conclusion. Perhaps as important, ED’s four main spending streams support goals that appear to have commanded support from large majorities of Americans for several generations. Our report’s evidence, and the long-term political dispositions of America’s citizenry, supports the reform of ED, but not its elimination.

We wish to make this distinction clear not least because a great many education reformers have sought to eliminate ED entirely. We understand the rationale for this goal, and we are sympathetic to it, but we have not embraced it for this report.

The long history of effective federal attention to education before ED, as well as the continued vitality of federal education spending outside ED, explains why many reformers have sought to eliminate ED entirely. If the federal government could attend effectively to education policy before the creation of ED in 1980, surely it can do so again? And indeed, federal education policy doubtless could function without ED. But ED cannot be eliminated until a reformist president, a reformist majority of the House, and a reformist supermajority of sixty senators decide that it must go—and that is not likely in the foreseeable future.5 If ED is likely to persist anyway, it is reasonable to continue to locate within ED the responsibility for core federal educational tasks: Title I funds, special education funds, Pell Grants, and direct student loans.

Other education reformers have emphasized the reduction of the ED bureaucracy as much as possible, both by eliminating unnecessary and counterproductive programs and by replacing bureaucratically administered programs with block grants to the states and portable grants of money to individuals. We also are sympathetic to these aspirations—but we focus on the first half of that agenda, eliminating unnecessary and counterproductive programs. We also favor the simplification of existing formula grants, ideally in ways that would make it easier for them to be converted at some later point into block grants to the states and portable grants of money to individuals. But we do not ourselves make the recommendation to terminate ED’s responsibility for disbursing formula grants.

Further, we favor substantial action to rein in ED’s discretionary power. Policymakers should focus especially on restraining ED’s lawless “forgiveness” of student loans and its ever-increasing abuse of OCR. Our recommendations in this arena, however, focus on brief statements of what needs to be done rather than detailed sketches of how this should be done. ED has acted without textual statutory warrant for much of what it does for many decades now and—especially with reference to the Biden administration’s policy on student loans—in ways that seem completely lawless. We are not sure that any parchment barrier can restrain policymakers and bureaucrats who intend to engage in arbitrary and/or lawless conduct. If ED persists in lawless conduct, the case for eliminating ED entirely must grow far stronger. But for now, we will simply sketch what should be ED policies and propose reforms to ED that will maximize its ability to forward the public welfare.

Our proposed reforms follow these leading principles:

- Accountability to the public and to policymakers;

- Nondiscrimination among American citizens;

- Rationalizing ED’s program structure;

- Prioritizing practical and achievable reform; and

- The possibility of reserving power to ED to restrain local activist bureaucracies.

ED is now so sprawling and complex that it cannot properly be held accountable, either by federal lawmakers or by the public. Our recommendations aim not to eliminate ED, or even to reduce its scope simply to reduce its scope, but rather to simplify its operations so that federal lawmakers and the public will be able practically to oversee ED and hold it accountable to its purpose. While we believe that ED would operate as well or better with a slimmer and more focused budget, the structure of our recommendations allows for lawmakers to provide a constant total budget to ED while reforming its internal architecture. We hope that the structure of our recommendations will give reformist policymakers the ability to make necessary compromises to achieve legislative majorities.

Our recommendations also aim to make the ED regulatory process more accountable to federal lawmakers and the public. ED, like far too much of the federal government, effectively has become a lawmaking body by means of Dear Colleague Letters, Significant Guidances, and the rest of an autonomous regulatory machine. ED has done particular damage by perverting civil rights law to enforce race and sex discrimination within and impose gender ideology on K–12 schools, colleges, and universities. We recommend that the regulatory process also be simplified and made more accountable to Congress. Moreover, our recommendations to simplify ED’s programmatic structure should make the regulatory process more accountable. ED’s regulatory power lies not least in the fact that K–12 schools, colleges, and universities depend financially upon a host of different programs, each of which is affected by ED regulations. To simplify the programmatic tangle is to simplify the regulatory labyrinth, thereby enabling education reformers to tame ED’s abuse of its regulatory power.

In addition to accountability, our reforms emphasize nondiscrimination, especially nondiscrimination by race or sex. No government programs should discriminate among American citizens or facilitate predictable discrimination by ED bureaucrats. While we generally favor practicable reform, we champion the outright elimination of ED programs that serve to discriminate. We make an exception for America’s historical support of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities (TCCUs). However, we support those programs that support HBCUs and TCCUs as institutions; such support should not be used as a fig leaf for race discrimination among American citizens.

We recommend rationalizing ED’s program structure by relocating many programs to other portions of the federal government. We believe that rationalizing ED will make it easier to establish accountability over education and that many of these programs are more logically located in different administrative units. We realize, however, that simply relocating programs may just preserve certain ineffective or counterproductive programs in new homes and that it will have little net effect to reduce federal power over American education. Our relocation recommendations should be taken as provisional; policy reformers may wish to revisit these programs once they have been relocated away from ED.

We recommend practical reforms. While we admire thoroughgoing and principled plans to reform or eliminate ED, we believe it will be most useful to provide recommendations that policymakers can use to establish priorities and to engage in a first round of reform, which may be the basis for more thoroughgoing reform at a later point. Bluntly, our recommendations will preserve the vast majority of ED spending, albeit in a simpler form that allows for greater accountability and transparency. We do not intend our recommendations to be an end to ED reform, but we would rather policymakers achieved these reforms first and only then consider what should be done next.

We recommend, finally, that reformers consider the possibility of reserving power to ED to restrain local activist bureaucracies. This recommendation does not align with our other recommendations, which largely would reduce ED’s size, scope, and power. Yet if ED policies originally prompted many public and private educational institutions to adopt discriminatory and illiberal policies, the distributed activist bureaucracies that ED fostered will continue to forward discriminatory and illiberal policies, even absent further support from ED. ED, indeed, may be the only institution that can restrain these distributed activists. We generally recommend preserving ED not least with this function in mind. We particularly recommend to reformers that they consider concrete, detailed ways that ED may be used as a palladium of liberty against distributed activists and thereby counter as much as possible the harm it has caused.

We have structured our report in this fashion:

- A Map of the Territory: A brief outline of ED’s organizational structure and of how it works.

- History: A history of ED since its creation in 1980, focusing on its programs and its regulations. This history will orient readers and provide context for the Central Audit and the case studies.

- Central Audit: A detailed analysis of the current structure of ED and of the effectiveness of its different programs as they pertain to K–12 education.

- Case Studies: Case studies on the effects of ED programs and policies on three school districts: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Winchester, Virginia; and Ashland, Ohio. We have selected these case studies to include urban, suburban, and rural school districts.

- ED’s Programmatic Structure: Roadmap to Reform: A catalogue of every office and program within ED, itemizing which should be retained, which relocated, and which eliminated.

- Policy Recommendations: A series of policy recommendations for the public and policymakers.

- Conclusion: Final conclusions.

Our recommendations are generally indebted to previous reformers. We are especially indebted to Mandate for Leadership, which provides a recent consensus of education reform priorities for ED.6 The Federalist Society has facilitated the publication of a great many legal articles articulating the nature of ED regulatory abuse, as well as preferred solutions. We are indebted to a host of education reformers, whether or not they are explicitly footnoted. We hope that this report will build upon and contribute to the broader education reform policy conversation.

We are especially grateful to the Arthur N. Rupe Foundation, which has provided funding for this report—and, within the Rupe Foundation, to Mark Henrie’s support and goodwill.

THE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT: A MAP OF THE TERRITORY

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. Department of Education is a complex organization—its component parts are referred to by a mind-numbing assemblage of departmental names and acronyms, and it refers to policies and administrative vocabulary by means of an equally mind-numbing jargon. The reader needs an introduction to orient him to this user-unfriendly landscape. A glossary would simply reproduce the mind-numbing jargon in alphabetical format, which would not be much of an improvement. We provide this map of the territory, thematic in structure, as a more engaging way to introduce the reader to this language.

This map includes Organizational Structure, Funding Structure, Statutory and Judicial Background, Race and Sex Discrimination, ED Professional Vocabulary, Other Parts of Government, and Reforming Ideals.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

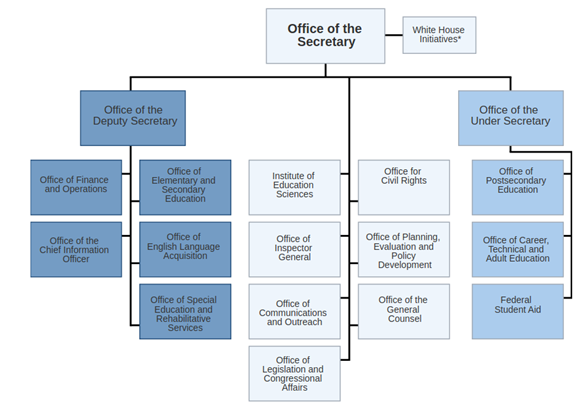

The Department of Education (ED, for Education Department), run by the Secretary of Education via the Immediate Office of the Secretary of Education, oversees the large majority of federal education spending. Within ED, the Office of the Deputy Secretary generally oversees Kindergarten–Grade 12 (K–12) education, while the Office of the Under Secretary oversees postsecondary (vocational training, college, graduate school) education. Several other offices report directly to the Secretary of the Education.

A great many individual offices distribute ED funds. These are the largest nine:

- The Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (OESE) runs the bulk of K–12 programs.

- The Office of Postsecondary Education (OPE) runs the bulk of postsecondary programs.

- The Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS) specializes in education for the mentally and/or physically handicapped (euphemistically called special education); it is also responsible for helping people recover from or minimize the effects of physical or mental impairment (rehabilitative services).

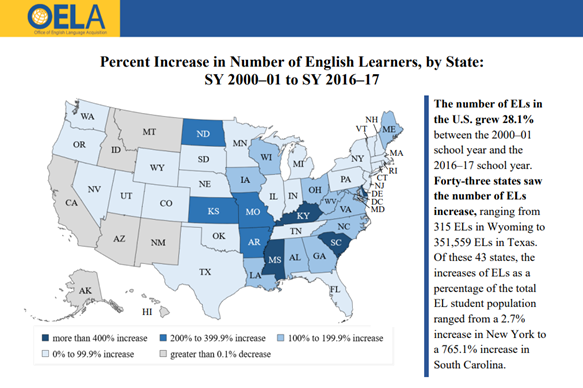

- The Office of English Language Acquisition (OELA) specializes in programs (mostly K–12) to help students learn English.

- The Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education (OCTAE) specializes in adult education, vocational training (education for skilled crafts), and community colleges.

- The Institute of Education Sciences (IES) provides statistics, research data, and academic scholarship intended to improve education policy.

- Federal Student Aid is in charge of federal assistance to postsecondary students, including grants (money given outright, especially by way of the Pell Grants for poorer students) and loans (money given with the expectation that it will be repaid, especially by way of the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan Program).

- The American Rescue Plan (ARP) is a temporary program, passed during the COVID-19 pandemic, to provide emergency funds for K–12 schools.

- The Education Stabilization Fund (ESF) is a temporary program, passed during the COVID-19 pandemic, to provide emergency funds for K–12 schools and postsecondary education.

ED runs hundreds more offices and programs within these nine large offices. Of these hundreds of offices and programs, we judge that the reader should be familiar with the following offices and programs.

Within the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (OESE):

- Education for the Disadvantaged disburses most ED money for school districts with a lot of poor students.

- The Office of Indian Education (OIE) disburses most ED money for federally recognized Indian tribes.

- The Office of Migrant Education (OME) disburses most ED money for migrant children (children whose parents move regularly from school district to school district).

- School Infrastructure Programs (SIP) disburses money for K–12 school infrastructure (e.g., buildings, facilities).

- The Office of Safe and Supportive Schools (OSSS), which runs Safe Schools and Citizenship Education, disburses ED money for emergency management, mental health, and nebulously defined programs to improve “school climate.”

- The Office of Formula Grants is in charge of formula grants (grants disbursed according to a predetermined formula set by Congress).

- The Office of Discretionary Grants & Support Services (ODGSS) operates miscellaneous K–12 programs, including charter schools (public schools outside the regular public K–12 school system) and school choice programs (programs that allow parents to choose to use tuition funds in either public or private K–12 schools).

- School Improvement Programs (SIP) operates miscellaneous K–12 programs, including State Assessments (which helps states to operate state-wide or school district tests) and the Rural Education Achievement Program (REAP) (which gives extra financial assistance to rural school districts).

Within the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS):

- The Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) disburses most ED money for educating the mentally and/or physically handicapped (special education).

- The Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA) disburses most ED money for helping people recover from or minimize the effects of physical or mental impairment (rehabilitative services).

Within the Office of Postsecondary Education (OPE):

- Institutional Service disburses ED money for miscellaneous small programs, including a great many dedicated to race discrimination on behalf of black, Hispanic, Asian American, and Native American students.

- International and Foreign Language Education (IFLE) disburses ED money to support education abroad or education intended to help America operate internationally, especially foreign language instruction.

- Student Service disburses ED money for miscellaneous programs, especially the TRIO Programs, which are intended to help prepare high-school students for college education.

ED operates another ten offices that round out its work:

- The Office for Civil Rights (OCR), which has greatly abused its powers to promote a progressive policy agenda, takes legal measures to ensure that no education institution receiving ED money violates civil rights law (generally involving race discrimination) or Title IX (generally involving sex discrimination).

- The Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development (OPEPD) provides oversight, evaluation, and advice to help operate the rest of the ED.

- The Office of the General Counsel (OGC) provides legal services for the Education Secretary and the rest of ED.

- The Office of Communications and Outreach (OCO) handles ED’s public relations.

- The Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO) handles ED’s computers.

- The Office of Finance and Operations (OFO) handles ED’s finances.

- The Office of the Chief Economist (OCE) provides economics research for ED.

- The Office of Inspector General (OIG) makes sure that there’s no fraud or waste in ED spending.

- The Office of Legislation and Congressional Affairs (OLCA) communicates with Congressmen and Senators.

- The Boards and Commissions (or Boards and Committees) are ten different groups of appointees from outside ED, who advise ED on particular matters and sometimes help make ED policy.

FUNDING STRUCTURE

Each year, ED states what funds it wants, and for what purposes, in its annual Budget Request. Congress (House and Senate) normally provides money each year for ED in its Appropriation—which can differ considerably from the Budget Request. In recent years Congress has frequently failed to pass regular appropriation bills. Instead it passes temporary, stopgap continuing resolutions (CR). These CRs have become regular enough that many ED documents now routinely use the term Annualized CR to refer to what is, in effect, the year’s appropriation.

Much of ED spending is divided between formula grants (grants disbursed according to a predetermined formula set by Congress) and discretionary grants (grants disbursed at levels set by Congress as it desires). Individual Congressmen and Senators also can earmark funds—appropriate special funds for ED to spend money for individual projects. ED classifies earmarked funds as K12 Congressionally Funded Community Projects and Postsecondary Earmarks.

ED funds for poor K–12 students are mostly formula grants authorized by Title I of the Higher Education Act. Title I Grants are meant to help schools and school districts with high proportions of poor students. Congress now distributes these funds by means of four separate formula Title I-A Grants: Basic Grants, Concentration Grants, Education Finance Incentive Grants, and Targeted Grants. These four Title I-A Grants are disbursed to local educational agencies (LEAs), which are any school district or other local administrative body that provides public schooling. These formulas formally ensure that Title I funds mostly go to poor schools—although education reformers have noted that, informally, they also ensure that a portion of Title I funds is distributed to as many congressional districts as possible.

Title I-C Grants, Title I-D Grants, and Title IV-A Grants, among other functions, help states educate migrant, neglected, delinquent, and at-risk children and youth. These are generally distributed to state educational agencies (SEAs), state bureaucracies that then distribute the funds to LEAs at their discretion.

Title II Grants support a variety of ED discretionary grants, such as those designed to improve literacy. They also fund a formula grant program for students in juvenile detention.

Title III Grants help students learn English. They include formula grants, distributed to the states to distribute in turn to LEAs, and discretionary grants.

Title VI Grants help students learn foreign languages.

ED funds for handicapped students are mostly IDEA Grants—formula grants distributed under the authority of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Part B Formula Grants, distributed to the states, help states give handicapped children a free, public education. The two main Part B Formula Grant programs are Grants to States (children ages 3 to 21) and Preschool Grants (children ages 3 to 5). Part C Formula Grants, also distributed to the states, help states care for handicapped infants and toddlers. Its Grants for Infants and Families help states care for children ages 0 through 2, along with their families. ED also disburses competitive discretionary grants under Part B and Part D to improve education for the handicapped.

Congress also imposes unfunded mandates on the states via IDEA. Congress requires the states to provide a minimum level of education for handicapped children but does not provide them the funds to pay fully for that minimum level of education.

Education reformers often propose replacing ED’s funding structure by a partial or total switch to block grants (no-strings disbursement of ED money to the states, which allows them complete discretion regarding how the money should be spent) and/or portable grants (grants to individuals and families, which they may then use in any public or private institution). The existing ED Ed-Flex program is a step in the direction toward block grants, since it provides states more flexibility in how they use ED funds.

STATUTORY AND JUDICIAL BACKGROUND

A great many laws authorize and govern ED’s behavior. Some of these predate the establishment of ED in 1980 and governed its programs when they were part of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. These laws include:

- The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) (1965), which began regular federal funding of and intervention in K–12 education. ESEA has been modified by the Education Consolidation and Improvement Act (1981), which simplified ED programs and constrained ED authority; by the Improving America’s Schools Act (1994), which increased from two to four the number of formula grants for poor K–12 students; by the No Child Left Behind Act (2001), which increased federal oversight and accountability measures; and by the Every Student Succeeds Act (2015), which rescinded some federal oversight and accountability measures.

- The Higher Education Act (HEA) (1965), which began regular federal funding of and intervention in postsecondary education. HEA has been modified by the Student Loan Reform Act (1993), which turned most college student loans into direct loans from ED; by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act (2010), which ended all federal loan programs except the Federal Direct Loan Program; and by the FAFSA Simplification Act (2020), which was supposed to simplify the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), the standard form that students use to apply for ED college loans.

- The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (1975), which began regular federal funding of and intervention in special education. This act was reauthorized and renamed as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (1990).

- The Bilingual Education Act (1967), which authorizes dedicated funding to help students learn English.

- The Indian Education Act (1972), which authorizes dedicated funding for American Indian education.

- The Carl D. Perkins Vocational and Technical Education Act (1984), which authorizes dedicated funding for career and technical education.

- The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (1987), which authorizes dedicated funding to help homeless students.

- The Education Sciences Reform Act (2002), which created the Institute of Education Sciences to house ED data collection and education research.

- The CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security) Act (2020), the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (2021), and the American Rescue Plan Act (2021), which gave hundreds of billions of dollars of emergency funding to education institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) (1974) and the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment (1978), which both establish parental rights and student rights to access information and to privacy.

- The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) ensures that all recipients of ED funds comply with all civil rights laws, including the Civil Rights Act (1964) (Title VI prohibits racial and ethnic discrimination); the Education Amendments (1972) (Title IX prohibits sex discrimination); the Rehabilitation Act (1973) (Section 504 prohibits discrimination against the disabled); the Equal Educational Opportunities Act (1974), which proscribes discrimination and segregation in schools and prescribed students’ equal participation in school instruction; the Age Discrimination Act (1975), which prohibits discrimination on the basis of age; the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) (Title II prohibits public discrimination against the disabled); and the Boy Scouts of America Equal Access Act (2002), which prohibits discrimination against designated youth groups.

- The Administrative Procedure Act (1946), which governs much of how ED operates, establishes regulations, adjudicates cases, and interacts with the public.

The first great legislative act to provide federal support for higher education was the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (1944), also known as the G.I. Bill. ED’s involvement in higher education builds informally upon the G.I. Bill, but there was no administrative continuity between this legislation and the Higher Education Act.

Several Supreme Court judicial decisions also have governed ED’s behavior, as well as American education policy more generally. These include:

- Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971), which incorporated “disparate impact” theory into American law and forbade the use of employment tests with disparate racial effect, unless they were directly and narrowly job-related.

- Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), which authorized “diversity” as a way to euphemize and disguise identity-group quotas in college and university admissions.

- Plyler v. Doe (1982), which required school districts to provide a free public education to illegal aliens.

- Grove City College v. Bell (1984), which held that ED could enforce Title IX regulations on an educational institution that enrolled students who received federal assistance but that the enforcement only applied to the institution’s financial aid department and not to the institution as a whole. Grove City prompted Congress to pass the Civil Rights Restoration Act (1987), which applied ED enforcement to every part of educational institutions that enrolled students who received federal assistance.

- Gebser v. Lago Vista Independent School District (1998) and Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education (1999), which, along with ED’s guidance Sexual Harassment Guidance: Harassment of Students by School Employees, Other Students, or Third Parties (1997), redefined sexual harassment as sex discrimination, and thus within OCR’s enforcement remit.

- Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College (SFFA) (2023) and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina et al. (2023), which jointly held that race-based affirmative action programs in college admissions were unconstitutional.

- Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2024), which overturned the Chevron doctrine of deference to federal agencies, and which theoretically weakened the ability of ED to impose its will by administrative means such as Dear Colleague Letters (DCLs), case resolutions, and rulemaking in general.

RACE AND SEX DISCRIMINATION

A great deal of ED policy is bound up with race discrimination among American citizens, generally to support informal race quotas framed in such a way as to skirt the Supreme Court prohibition of formal race quotas. ED’s informal race quotas used the euphemism of affirmative action early on. After Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), the euphemism of diversity increasingly supplanted affirmative action—and expanded the range of beneficiaries of these informal quotas much beyond the originally intended beneficiary, black Americans. In the last generation, equity and inclusion have become new euphemisms. Ideologies that have sprung up to justify these quotas, as well as the repression of words and deeds that oppose these quotas, include diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and critical race theory (CRT). ED programs and regulations whose very names convey the Department’s commitment to race discrimination include Equity Assistance Centers and Equity Requirements in IDEA. ED programs also camouflage their support for DEI and CRT via support for pedagogies such as social-emotional learning (SEL), which far too frequently conflate “emotional well-being” with “support for DEI and CRT.” ED fosters a great deal of race discrimination by its policies and programs. The Department has also encouraged race discrimination against Jews (antisemitism) through its selectively lax enforcement of civil rights law when Jews are victims.

Some of ED’s race discrimination overlaps with traditional American support for particular organizations and entities, and these should be distinguished. For example, America’s support for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), carried out via ED subunits such as the Strengthening Historically Black Colleges and Universities Division, is not necessarily an obvious matter of race discrimination as are ED’s efforts via the Hispanic-Serving Institutions Division (HISD) or the Strengthening Institutions Division (SID)—although ED’s support for HBCUs can also be framed badly, as individual race discrimination rather than as institutional support.

America has legal commitments to federally recognized Indian Tribes, Alaska Native entities, and Native Hawaiians. ED funds disbursed to Indian Tribes are often directed to Tribal Education Agencies (TEA) and Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities (TCCU). ED programs that support these traditional American commitments, especially when they serve institutions rather than individuals, are not necessarily examples of race discrimination. These legal commitments now have programmatic corollaries to support Native American Language education, which can take place outside of tribal lands. A great many ED offices and programs for Indian education, Alaska Native education, and Native Hawaiian education, therefore, need to be considered carefully, to disentangle the appropriate fulfilment of traditional legal relationships from race discrimination among American citizens. E.g., Native Americans are an ethnicity rather than a legal entity; ED should not discriminate between American citizens for or against Native Americans, although, without engaging in race discrimination, it can provide support for Indian Tribes and for Native American Language programs.

Offices and programs that should be scrutinized regarding whether they support race discrimination include Rural, Insular & Native Achievement Programs (RINAP), Accessing Choices in Education, Alaska Native Education, Demonstration Grants for Indian Children, the Native American & Alaska Native Children in School (NAM) Program, Native American Language, the Native American Language Resource Center, the Native American Teacher Retention Initiative, Native Hawaiian Education, Native Youth Community Projects, and the State Tribal Education Partnership Program.

ED also abuses its enforcement of Title IX prohibitions against sex discrimination by redefining sex discrimination to include a great many policies that were not originally intended by Congress when it voted for Title IX. Early on, ED took Title IX to require informal sex quotas for funding and participation, especially in K–12 athletics and college quotas. ED later expanded sex discrimination to include sexual harassment and sexual violence (including rape)—which, since sex discrimination law had lower due process requirements than criminal law, severely damaged America’s traditional constitutional, legal, and procedural protections for citizens accused of crimes. ED also redefined sex to mean the arbitrary word gender; it thus interpreted sex discrimination laws without statutory warrant to provide legal protection for sexual orientation (homosexuals) and gender expression (gender identity, gender nonconformity, gender transition, transgender, and collective acronyms for a variety of categories of sexual orientation and gender expression including LGBT, LGBTQ, LGBTQ+, and LGBTQI+). Particular flashpoints for transgenderism debates include men participating in women’s sports and men using female locker rooms—issues where ED has coerced educational institutions to require both of these unfortunate policies.

ED frequently imposes race and sex discrimination on K–12 school districts and postsecondary institutions by means of the Office for Civil Rights (OCR). OCR purports to uphold antidiscrimination law (civil rights law, Title IX), but it imposes a great deal of discrimination in the name of antidiscrimination. Aside from supporting informal quotas, OCR upholds in many areas of education policy the disparate impact doctrine, which holds that policies with disparate racial effect—no matter how meritocratic, well-intentioned, or conducive to public welfare—violate civil rights law. ED has used the disparate impact doctrine to cripple K–12 school discipline policies, virtually all of which have disparate racial impact. ED also has hinted loudly that school systems must redirect their finances to avoid disparate impact (Resource Comparability); this proposal would terminate states’ and localities’ ability to tax and spend as they will and subordinate elected policymakers to OCR bureaucrats. OCR frequently uses Dear Colleague Letters (DCLs)—along with other forms of technically not obligatory significant guidance from ED to funding recipients—and case resolutions (resolution agreements) as bureaucratic devices to impose policy changes on K–12 school districts and postsecondary institutions by coercive administrative fiat. Significant guidance and case resolutions technically are not obligatory rules, so they sidestep both the requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act (1946) and the principle that major policy changes should be made by statutes drafted by elected representatives who are democratically responsible to the people.

ED’S PROFESSIONAL VOCABULARY

ED uses a very large amount of professional vocabulary—bureaucratic jargon, to put it bluntly. Some of the more important collections of ED’s professional vocabulary include:

Performance measures (performance metrics) vocabulary registers how ED assesses the effectiveness of its programs. Qualitative analysis is a euphemism for subjective reports with too little data. Quantitative analysis provides more data and more objectivity, although, all too frequently, ED does not provide any means to determine the return on investment of ED spending. Efficiency measures measure the performance of ED’s own bureaucracy.

English language instruction vocabulary includes bilingual education (different classes taught in different languages, most frequently English and Spanish); English language proficiency (ELP) (a minimum ability to speak, write, and understand English); English learners (students who need dedicated support to learn English, generally from homes where their families don’t speak English); the Language Instruction Educational Program (LIEP) (programs dedicated to help students learn English); and multilingualism (multilingual, multilingual literacy), a euphemism for a weakening commitment to teaching students English. ED acknowledges that English language instruction is primarily for immigrants and their children; it does not acknowledge how much English language instruction serves illegal aliens and their children, save by euphemisms such as illegal immigrants and undocumented Americans.

Accreditation vocabulary concerns the accrediting organizations, particularly the seven regional accrediting organizations, that provide general undergraduate accreditation. Accreditation makes a postsecondary institution eligible to receive federal student aid, including both grants and loans. These accrediting organizations theoretically are independent of ED, but ED exercises ultimate control by accrediting the accreditors. It does this by means of the National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity.

Assessment vocabulary largely concerns state and school district examinations that are supposed to provide the public a transparent measure of how well K–12 schools educate children. ED’s State Assessments, State Assessment Grants, and Competitive Grants for State Assessments are part of the Department’s organizational jungle concerned with assessments. The independent National Assessment Governing Board is also affiliated with ED. The leading provider of standardized assessments is the College Board, which is responsible for the Standardized Aptitude Test (SAT) and Advanced Placement (AP) examinations and courses. State assessments in English language arts and mathematics have been heavily influenced by the mediocre Common Core model examinations, not least because of federal financial inducements.

OTHER PARTS OF GOVERNMENT

Other parts of the federal government provide education services already and/or should take over parts of what ED now does. These include:

- The Department of Agriculture (USDA), which provides funding for school lunches by means of its National School Lunch Program (NSLP).

- The Department of Defense (DOD), whose Department of Defense Education Activity runs a worldwide school system for the children of our soldiers and officers, and whose Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center supports foreign language instruction.

- The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—which, before 1980, was the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare—includes the Administration for Community Living, which ought to take over ED’s Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA); Social Services, which ought to take over the Office of Migrant Education and several smaller ED programs; and Emergency Preparedness and Response, which ought to take over ED’s Disaster Recovery Unit.

- The Department of the Interior (DOI), whose Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) includes a Bureau of Indian Education (BIE), which ought to take over ED’s Office of Indian Education (OIE).

- The Department of Justice (DOJ), whose Civil Rights Division ought to take over ED’s Office for Civil Rights, and whose Federal Bureau of Prisons provides education for students in jail or juvenile detention.

- The Department of Labor (DOL), whose Employment and Training Administration ought to take over ED’s Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education (OCTAE).

- The Department of State (DOS), whose Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs supports education abroad, and which ought to take over ED’s International and Foreign Language Education (IFLE) program.

- The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), whose Education and Training ought to take over all ED programs for veterans.

- The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), whose Arts Education ought to take over all arts education programs in ED’s Well-Rounded Education Programs Office (WEPO).

- The National Science Foundation (NSF), whose Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences ought to take over many ED research programs, especially those housed in the Institute of Education Sciences (IES).

REFORMING IDEALS

Education reformers generally wish to reform ED policies to restore freedom (liberty). They favor strengthening First Amendment rights, including freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of religion (both of individuals and of religious organizations), as well as due process rights to be treated fairly in accordance with established laws and procedures. These liberties are particularly threatened by OCR’s coercive imposition of DEI and CRT policies. Educational reformers support individual liberty, but they also support parental rights to raise and educate their children as they will.

Educational reformers also favor increasing parents’ liberty to choose a school for their children. This principle is articulated in goals such as charter schools (administratively autonomous public schools), school choice (the ability to choose which public school to attend, or, more expansively, public support for attending a private school), and education savings accounts (portable public money that parents can use for either public schools or private schools). ED offices and programs that support these goals include School Choice & Improvement Programs (SCIP) and the Federal Charter School Program.

Education reformers also favor reform in support of the national interest. Such reforms include greater scrutiny of the influence exerted by great power rivals such as China or by bigoted dictatorships such as Qatar. Such scrutiny particularly concerns foreign financial support of American educational institutions and criminal actions by foreign students, such as antisemitic intimidation.

Education reformers, finally, favor gifted education—dedicated education for smart students. ED programs that support this goal include the Jacob K. Javits Gifted and Talented Students Education Program.

CONCLUSION

This map of the Education Department is not comprehensive. To name every ED program would be, in effect, to repeat this report. This outline, however, should orient the reader and make our report easier to understand.

HISTORY

PROGRAMS

The major programs and mandates that make up the U.S. Education Department (ED) are older than the Department itself. While the Department—including its associated cabinet position, the secretary of education—was created in 1980, Title I aid to the states and local educational agencies (LEAs) dates back to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. Special education monies date back to 1975, with the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act. Bilingual education support began with the Bilingual Education Act of 1967, while much of the dedicated education spending for American Indians dates to the Indian Education Act of 1972. The Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974 prohibited discrimination and segregation in schools and prescribed students’ equal participation in school instruction. The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, enacted the same year, both gave substantial privacy rights to students and gave parents the rights to access and control the disclosure of information about their children.

In higher education, Pell Grants and the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan Program (under various previous names) also draw upon the Higher Education Act of 1965, which was revised in 1972 and 1978. It is worth adding that the House and Senate committees devoted to education date back to 1867 and 1869, respectively, and that major initiatives such as the World War II G.I. Bill also predated ED.

Moreover, a great many other education programs also continue to be housed outside ED. The Department of Defense runs an entire school system under Department of Defense Education Activity, the Department of Justice’s Federal Bureau of Prisons offers an array of education programs, and education funding is provided by the National Science Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. An astonishing number of federal agencies share responsibility with ED for supporting education.

Yet the greatest changes in federal education policy—and, consequently, in American education as a whole—have proceeded within ED and under the leadership of the education secretary since the Department’s creation in 1980. A brief catalogue of the most important judicial, statutory, and programmatic developments since 1980 includes:

- The Education Consolidation and Improvement Act (1981) consolidated many ED programs, notably by converting much Title I spending into formula grants to LEAs, and relegated substantial education authority from ED to the states.

- The Carl D. Perkins Vocational and Technical Education Act (1984) authorized substantial ED funding for career and technical education.

- The Supreme Court decision Grove City College v. Bell (1984), which held that 1) ED could enforce Title IX regulations (and, by extension, all ED interpretations of civil rights law) on educational institutions that enrolled students who received federal assistance; and 2) that the regulation only applied to the institution’s financial aid department and not to the institution as a whole.

- The Civil Rights Restoration Act (1987) overturned the second part of Grove City College v. Bell (1984) and declared that ED’s enforcement of civil rights law applied to every part of educational institutions that enrolled students who received federal assistance.

- The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1990 reauthorized and renamed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (1975), with revisions including greater attention to the individual education of special education students and an even stronger emphasis that special education should take place in the least restrictive environment.

- The Student Loan Reform Act (1993) transformed the bulk of federal student loans from guarantees of student loans secured from private lenders (Federal Family Education Loan Program) to student loans provided directly by ED.

- The Improving America’s Schools Act (1994) increased from two to four the number of separate Title I formula grants disbursing funds to states and LEAs: Basic Grants (1965), Concentration Grants (1978), Targeted Grants (1994), and Education Finance Incentive Grants (1994).

- The Federal Charter School Program (1994), established by amendment of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, provided federal funding to states and LEAs to manage and develop charter schools.

- The No Child Left Behind Act (2001) revised the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (1965) and added far greater federal promotion of and oversight of standardized testing and other education accountability measures.

- The Education Sciences Reform Act (2002) created the Institute of Education Sciences to house and promote ED data collection programs, including the National Center for Education Research, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, and the Regional Educational Laboratory Program.

- The Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act (2010) terminated the Federal Family Education Loan Program and left the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan Program as the sole federal student loan program.

- The Every Student Succeeds Act (2015) revised the No Child Left Behind Act (2001) and relegated the responsibility for portions of standardized testing and education accountability from the federal government to the states.

- The CARES Act (2020), the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (2021), and the American Rescue Plan Act (2021) directed hundreds of billions of dollars of emergency funding to education institutions, funding that was justified as an amelioration of the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

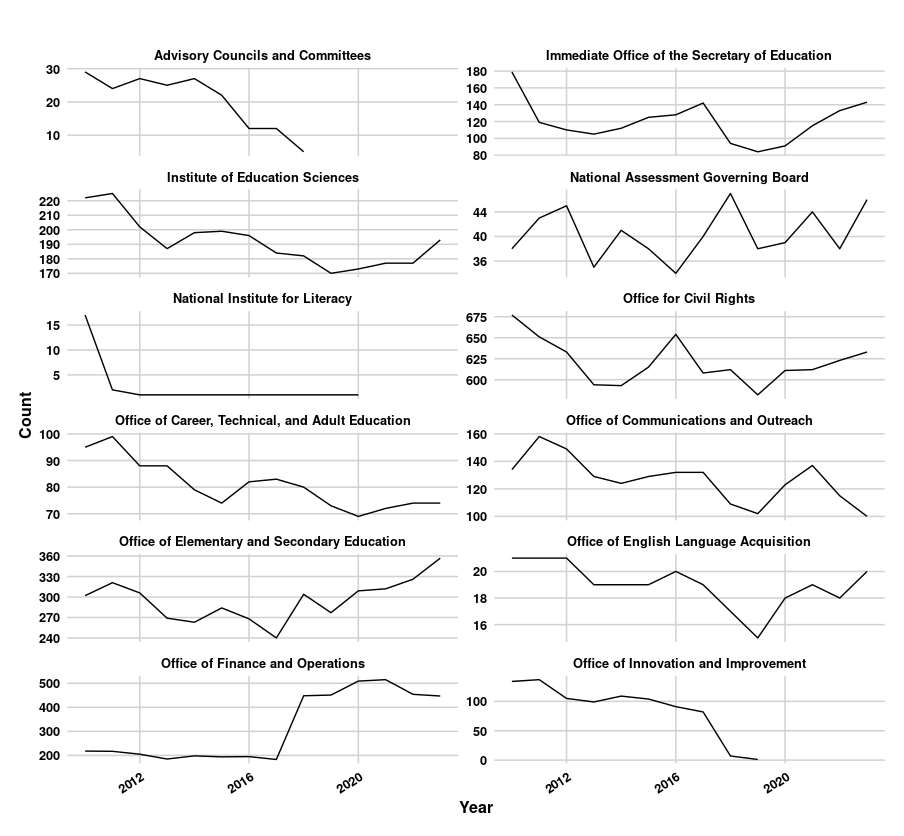

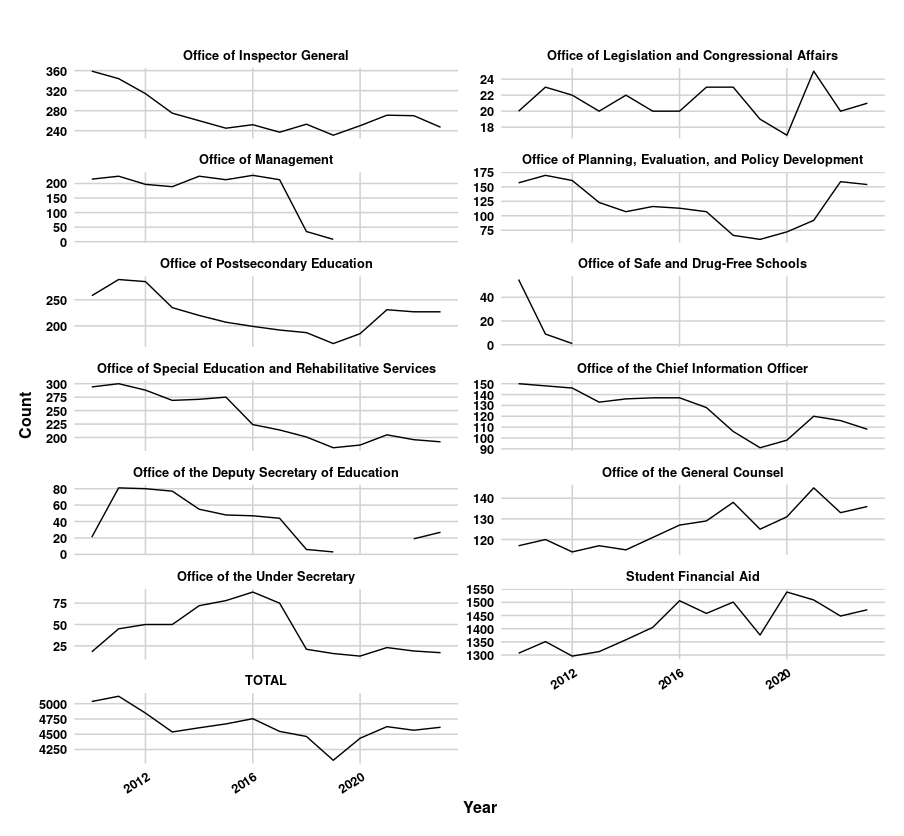

ED itself employs about 4,400 employees, but ED has done far more to increase the size of state and local education bureaucracies.7 The federal government funds 41% of state education agency salary costs, and these state agencies employ ca. 48,000 employees. An extraordinary number of state and local education administrative personnel, moreover, work to satisfy federal mandates and accountability requirements.8 One very significant measure of ED’s growing and intrusive influence in American education is the distributed state and local education bureaucracy—invisible on the federal books—that complies with ED directives and requirements.

United States Secretaries of Education

|

Name |

Dates in Office |

|

Shirley Hufstedler |

1979–1981 |

|

Terrel Bell |

1981–1985 |

|

William Bennett |

1985–1988 |

|

Lauro Cavazos |

1988–1990 |

|

Lamar Alexander |

1991–1993 |

|

Richard Riley |

1993–2001 |

|

Rod Paige |

2001–2005 |

|

Margaret Spellings |

2005–2009 |

|

Arne Duncan |

2009–2016 |

|

John King Jr. |

2016–2017 |

|

Betsy DeVos |

2017–2021 |

|

Miguel Cardona |

2021–2025 |

|

Linda McMahon |

2025–present |

REGULATIONS

Another measure is the growing weight of ED regulations, especially in its abusive enforcement of civil rights and Title IX law. ED has arrogated to itself effective lawmaking power, to an increasingly radical effect. The growing size and complexity of ED programs is the essential precondition of these administrative impositions. States, LEAs, and postsecondary institutions have become financially dependent on ED—and they have acquired their own parallel bureaucracies, which are either acquiescent to or eager handmaidens of ED bureaucrats and their dictates. ED’s power to dictate depends on its power to bring civil rights and Title IX law to bear on colleges’ and universities’ eligibility to receive federal money.

ED, precisely, can exert financial, administrative, and legal pressure on institutions that are deemed to have discriminated illegally on grounds of race and sex, as spelled out in the complex of authorizing civil rights and Title IX legislation within its purview. ED’s abuse of its regulatory power ultimately derives from attempts to redefine progressive policy goals as remediations of violations of civil rights and Title IX law.

The five most publicized (overlapping) categories of such abuse are:

- Informal race and sex quotas;

- Disparate impact theory, especially as applied to race and sex;

- The illegal expansion of the scope of antidiscrimination law;

- Abrogations of liberty (due process, free speech, and religious freedom);

- The use of Dear Colleague Letters and Resolution Agreements to sidestep the publicity requirements of the Administrative Procedure Act.

While these abuses have been the most publicized, we would like to emphasize that ED issues a host of dry financial and administrative regulations and Dear Colleague Letters (DCLs), which collectively hollow out state sovereignty and local decision-making power. These may be no more unconstitutional than the entire hypertrophied federal administrative state—but they are no less unconstitutional. While we will not focus here on how ED’s regulatory and fiscal power inexorably degrades the federalist reservation of power to the states and the people, we urge the reader to keep in mind this power and its effect.

We also will not emphasize the complementary role of activist nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), who use a “barratry” strategy to activate the administrative state—complaints that bring (the threat of) ED intervention to bear and thereby bring about desired policy changes.9 The UC Berkeley School of Law, for example, altered its admissions policy in 1997 following the announcement of an OCR investigation. That OCR investigation was in turn sparked by a complaint by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the California Women’s Law Center, the Asian Pacific American Legal Center of Southern California, Equal Rights Advocates, and La Raza Centro Legal.10 Readers should presume that activist NGO complaints and lawsuits systematically set up ED abuses of power.

INFORMAL RACE AND SEX QUOTAS

ED has supported policies that apply informal race and sex quotas to various aspects of the education system—often, as we shall see below, by way of disparate impact theory. These quotas did not originate with ED—but ED has lent support to such quota systems by investigating failures to have “nondiscriminatory” proportions of protected identity groups as violations of civil rights law or Title IX.

Title IX provided an early and powerful example of such intervention. In 1979, even before the creation of ED, the Office for Civil Rights in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare devised a three-prong system for testing whether college athletics discriminated against women—one prong of which, and the most effective as a legal safe harbor for educational institutions, was a test of the proportion of support going to women’s athletics: “Whether intercollegiate level participation opportunities for male and female students are provided in numbers substantially proportionate to their respective enrollments.”11 Since then, Title IX has exerted steady pressure on educational institutions to provide as many informal quotas as necessary to secure such proportionality. Melinda Sidak judged that, by December 1997, “the transformation of Title IX from an equal opportunity and antidiscrimination law to a rigid and arbitrary quota system is now complete.”12

In the realm of race, we may confine ourselves to three examples of ED’s actions that exerted pressure on educational institutions to strengthen racial “proportions.” ED’s investigation of University of California law schools for racial discrimination closely followed the 1996 passage of Proposition 209, the referendum that prohibited race discrimination by the state of California. ED’s investigation seemed intended to nullify the effects of that referendum. As Jennifer Nelson wrote at the time, “the Clinton Administration decision to pursue the investigation is continued evidence that the Administration intends to use its bureaucratic powers to force state and local government agencies to continue using race and gender preferences—even in the face of court orders or voter initiatives to the contrary.”13 The language of Education Secretary Richard Riley’s 1997 DCL substantiates that judgment:

I want to confirm that the passage of Proposition 209, which would generally prohibit affirmative action under state law for women and racial minorities, has not changed the obligation of school districts and colleges to abide by federal civil rights statutes in order to remain eligible to receive Department funding, nor has it changed the obligations of schools participating in a small number of federal programs administered by the Department to consider race, as appropriate, under the terms of those programs. In addition, I want to express my continuing support for appropriately-tailored affirmative action measures, which are important tools in our efforts to ensure that all students achieve to high standards.14

In 2001, in the waning days of the Clinton administration, Secretary Riley cited in a DCL a disproportion of resources as a potential civil rights violation: “I am writing to call your attention to a serious issue that goes to the heart of our shared mission to ensure equal educational opportunity and to promote educational excellence throughout our nation—the problem of continuing disparities in access to educational resources.”15 In 2014, ED founded its DCL intervention in school discipline policies on a racial “disproportion” in school disciplinary actions.16 In this intervention, as the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty put it, the “Department of Education’s emphasis on the collection and monitoring of racial statistics and its demand that something be done if the numbers come out the wrong way is tantamount to setting impermissible race quotas for disciplinary outcomes.”17 ED, since its foundation, has exerted informal pressure to reinforce race and sex quotas—as we may also see, for example, in its Dear Colleague Letter: Title VI Access to AP Courses (2008) and Dear Colleague Letter: Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina et al. (2023).18

These examples, as we shall see, overlap with the effects of “disparate impact” theory and DCLs. What they all illuminate is an underlying logic to ED regulatory practice—ED applies informal pressure on educational institutions to maintain race and sex quotas in an increasingly broad range of their policies.

ED applies informal pressure. ED itself has not formally required quotas. Yet the Title IX prongs have been symptomatic of a countering presumption—namely, that a failure to achieve race and sex proportionality will also be taken as litigable and that some sort of informal quotas will serve as a practical safe harbor for an educational institution, one that is within spitting distance of a legal safe harbor. So likewise, with respect to race, the belief articulated by Secretary Riley in his 1997 DCL: “I continue to believe that appropriately-tailored affirmative action measures are educationally sound tools to remedy the effects of prior discrimination and to foster diversity at educational institutions.”19 American educational institutions have acted to impose informal quota systems not least because of the continuing heavy hints from ED that they will suffer investigations and lawsuits if they do not.

ED and its functionaries have also worked steadily to formulate various means by which they may formally bring their powers to bear, all in order to achieve this and other progressive policy goals. “Disparate impact” theory, for a notable example, has enabled progressives to redefine an extraordinary amount of their public policy goals as remediations of violations of civil rights and Title IX law.

DISPARATE IMPACT

The legal incorporation of “disparate impact” dates back to Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971), which forbade the use of employment tests with disparate racial effect20 unless such tests were directly and narrowly job-related. The disparate impact doctrine did not provide a formal judicial precedent for education—especially since the controlling statutory language in civil rights and Title IX law clearly forbade racially or sexually disparate treatment rather than disparate effect.21 The ambiguous authorization of affirmative action in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) nevertheless created informal pressure, and permission, to use disparate impact theory as a complement to the equally informal quotas of affirmative action.

Disparate impact theory, as applied to education, holds that any policy with disparate racial or sexual effect violates civil rights law. This explicitly contradicts the civil rights and Title IX statutes, as well as the tenor of major corollary judicial decisions,22 which state that what has been rendered illegal is discriminatory intent.

Indeed, disparate impact theory tends more generally to degrade the foundations of Anglo-American law, such as individual responsibility and the presumption of innocence. It also replaces individual competition on the grounds of merit with identity-group quotas. It furthermore is an engine of too-powerful and arbitrary government, since

- An equality of results among human beings never occurs by nature, not least because human beings make individual choices by free will that differ from one another in their consequences;

- An equality of results can only be achieved (if at all) by government intervention;

- As Mulder notes, “any policy or practice will benefit some groups more than others”; and

- Government must arbitrarily select among the infinity of inequalities that are worthy of litigation.23

To accept disparate impact theory is to grant excessive power to ED, or to any government agency granted power to “remedy inequalities,” to act arbitrarily and perpetually in pursuit of the unattainable.

These broader effects of disparate impact theory are reasons to oppose it politically. In the narrower confines of legal judgment, it is enough to say that disparate impact theory does not accord with the controlling statutory language in civil rights and Title IX law. ED can only claim to apply disparate impact theory through a studied unconcern about the statutory warrant for its powers.

ED nevertheless has repeatedly brought up disparate impact theory as a justification for its proposed actions. We already have mentioned Education Secretary Riley’s DCL that cited a disproportion of resources as a potential civil rights violation. Riley based this position particularly on disparate impact theory—although with evasive stipulations.

Title VI and its implementing regulations prohibit the disparate treatment of students based on race and national origin as well as policies or practices that have a discriminatory disparate impact by race or national origin. Disparity alone does not constitute discrimination; rather, the existence of a significant disparity triggers further inquiry to ensure that the given policy is educationally justified and that there are no alternative policies that would equally serve the recipient’s goal with less disparity.24

Secretary Riley’s DCL used ED’s interference in state and local taxation to require “intradistrict” and “interdistrict” financial transfers in order to equalize education spending on the progressive policy agenda: as Mulder noted, “the only way that OCR can achieve its goal is by forcing states and localities to remake their school funding systems. The reference to intradistrict and interdistrict funding disparities makes this plain.”25 Secretary Riley, in other words, articulated that a strategic progressive policy goal is to use ED to usurp state and local fiscal authority—the right to tax and spend—on the grounds that any “disparate impact” of existing education fiscal policy is a litigable violation of civil rights. ED followed up on Secretary Riley’s DCL with a successor DCL on Resource Comparability in 2014.26 ED steadily exerts informal pressure on states and school districts to alter their education fiscal policy, for fear of investigation and lawsuit.

ED’s intervention into school discipline policies also rests on the grounds of disparate impact.27 ED’s 2014 DCL on Confronting Racial Discrimination in Student Discipline stated that:

Although statistical and quantitative data would not end an inquiry under Title IV or Title VI, significant and unexplained racial disparities in student discipline give rise to concerns that schools may be engaging in racial discrimination that violates the Federal civil rights laws. … The administration of student discipline can result in unlawful discrimination based on race in two ways: first, if a student is subjected to different treatment based on the student’s race, and second, if a policy is neutral on its face—meaning that the policy itself does not mention race—and is administered in an evenhanded manner but has a disparate impact, i.e., a disproportionate and unjustified effect on students of a particular race.28

ED’s warning that any racially disparate impact in school discipline could be investigated or prosecuted as a violation of civil rights law has been unfortunately successful in destroying the will or the ability of school districts to exert proper school discipline:

As written and implemented, the Guidance has been criticized on three primary grounds. First, it creates a chilling effect on classroom teachers’ and administrators’ use of discipline by improperly imposing, through the threat of investigation and potential loss of federal funding, a forceful federal role in what is inherently a local issue. … Guidance has likely had a strong, negative impact on school discipline and safety.29

Similar ED disparate impact initiatives threaten standards assessments: in 1999, for example, ED distributed draft guidelines that would “challenge the use of standardized tests when they have a ‘disparate impact’ on racial or ethnic groups.”30 As Roger Clegg noted, this complaint revealed an obvious double standard at ED:

It has become something of an open secret these days that most selective colleges and universities … require Asians and whites to score at a particular level on the SAT or ACT in order to be admitted, but hold African Americans and sometimes Hispanics to a lower standard. … OCR has not complained during the Clinton administration about this practice—which, again, any reasonable person would conclude is discrimination in violation of Title VI, the statute that OCR is charged with enforcing.31

Indeed, any standard based on individual merit will inevitably have a “disparate impact” on some group; disparate impact theory logically requires ED to dismantle any accurate standards assessment.