Carol Iannone is editor-at-large of Academic Questions, 420 Madison Ave., 7th Floor, New York, N.Y. 10017; [email protected].

I often wonder whatever happened to the good ideas that emerged from the counterculture of the Sixties and Seventies. Yes, there were some, truth be told. A healthy skepticism about conventional medicine and medical protocols, for one, coupled with a desire for a broader sense of health—going beyond curing specific ills toward embracing a more natural and organic sense of well-being. But now some two thirds of Americans take prescription drugs on a regular basis without a thought, it seems, and even drugging children has become almost routine. Some drugs have been so overprescribed as to become problems in themselves. No doubt many of these prescriptions are doing good, but the larger picture of organic, more holistic well-being has faded. The airwaves (network, cable, radio) are filled with medical ads and pharmaceutical advertisements permitted in almost no other country, I’m told, and for an ever-expanding roster of ailments. As for healthy skepticism toward experts, it has yielded to servile compliance for many, enough at any rate to agree to suspend normal life for two years for fear of a disease with a 98 percent recovery rate, and to follow the mandates of health professionals who didn’t even appear to know what they were doing.

At that time too there was greater hope for the treatment of mental illness. Inspiring books such as the semi-autobiographical I Never Promised You a Rose Garden (also made into a film), and the non-fiction Dibs in Search of Self, both from 1964, offered some thought that even severe cognitive disturbances might be addressed in a natural interactive way. But one day, it seemed, the profession decided that we’re just mechanistic beings after all—a few dollars worth of chemicals to be adjusted with more chemicals and mixed with our watery parts—and all that hopefulness was gone. Psychiatrists turned exclusively to prescribing drugs, offering sufferers a lifetime of medication, troublesome side effects, and the sword of Damocles should they forget their “meds,” or try to do without.

There was also, in those years, a more expansive sense of living as a bracing adventure of self-discovery, of becoming the hero of one’s own life, as David Copperfield had put it. Books, fiction and nonfiction, such as The Lonely Crowd (1950), The Organization Man (1956), and The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1955 as novel, 1956 as film), had already suggested the inadequacy of mere material prosperity and career aspiration in the post-World War II world. The young office worker-protagonist of Billy Wilder’s beautifully fashioned film The Apartment (1960) lends his nearby Manhattan apartment to facilitate the sleazy adulterous couplings of his corporate superiors in order to further his own advancement, but through one thing and another learns to stand up and refuse them and “be a mensch,” Yiddish for a person of integrity. As people became freer and more prosperous, the wars and Depression behind them, attention turned away from material survival to the very meaning of life. Fantasy and myth became a vehicle to explore more directly the deeper questions that the official art and fiction of the time were equivocating about. For example, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (1954-5), C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-56), Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), even if written earlier, became popular reads of the time.

The first two are multi-part high fantasies in which the characters’ growth in confrontation with evil and necessity, their struggle to meet and overcome their challenges—no matter how dire, adverse, or unfair—are as much the story as the fabulous plots themselves.

Later on, Campbell became identified with his advice to “follow your bliss,” which sounds hippie-ish and new-agey, but The Hero with a Thousand Faces is much more than that. For one thing, it actually fulfills the brittle Edward Casaubon’s failed attempt to write “The Key to All Mythologies” in George Eliot’s novel Middlemarch (1871-2). But more important, masterfully treating myths from many cultures, Campbell found the controlling thread in the “hero’s journey,” a paradigm for individual growth and self-discovery in facing and overcoming whatever obstacles your destiny presents to you, and in realizing your responsibility to society, the world, and others as you return from your struggles with “boons” for your fellow man.

Some years later, filmmakers inspired by these books as children, teenagers, or young adults went on to make them into notable movies, or movies based on their ideals and themes. J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series (1997-2007) could be seen as an attempt to reprise some of these ideals for a new generation, although the effects on that generation seem uncertain.

Campbell developed a whole thrilling vocabulary, the “call to adventure” (and the unfortunate occasional “refusal of the call,” resulting in stagnation), the “threshold guardians” that want to hold you back, the “supernatural aids” that come unbidden to push you on, and much more, which, as fantastical as it may seem, actually becomes a way to understand ordinary life. Important too was the way these works allowed for reintroduction of the transcendent, a way of bringing God, or something like, back into the picture and into intellectual argument and discourse, in a time growing increasingly, if not aggressively, godless and secular. Certainly, it is proper to conduct argument along rational lines, but to completely eliminate the spiritual aspect, in what Father John Neuhaus termed in protest the “naked public square,” is excessively stringent and unhelpful. Campbell himself was an atheist, but he knew mythology and much of human history would not make sense without some understanding of the extra-material dimensions of life.

This was the case too with Alcoholics Anonymous and its powerful Twelve Step program, devoted to individual character transformation with reference to a “higher power,” that is, a higher power as individually and practically understood, not a doctrinal mandate. Founded in the middle of the Depression of the 1930s, its success prompted its application to an amazing array of other types of addictive maladies through the decades, from the rising problem of drug addiction in the Sixties and Seventies to video gaming today. And acquaintance with AA or Al-Anon naturally brought us to read one of its major inspirations, William James’s “other masterpiece,” as Jacques Barzun called it, The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), with its dazzling compendium of personal conversion experiences, together with James’s uncanny precision in describing spiritual aspiration in rational language.

A great deal of Holocaust literature began to emerge in the countercultural decades, too, and eventually to become accompaniments to study. What came through, along with accounts of the horrors, was the character and heroism of people confronted with the worst that man can do to man, but who preserved their humanity by exercising what choice for life they could even within horrendous circumstances. (Much later, I knew we had lost the energy of those terrible lessons to some lesser conception of facing adversity when, during a class discussion of Viktor Frankl’s 1946 book Man’s Search for Meaning, a student remarked that he would not accept such treatment, but would rather commit suicide.)

This kind of understanding also comported with immersion in the Western legacy of great works, whether formal, through a course of study, or informal, through personal reading. A look into the ancient Roman period would bring you to Augustine’s Confessions (397-400); into nineteenth century Scotland, to Thomas Carlyle’s quirky, imaginative Sartor Resartus (1831, with its incomparable tripartite description of individuation: the Everlasting No, the Center of Indifference, the Everlasting Yea); to nineteenth century New England, the essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Carlyle’s American counterpart, more or less, with his emphasis on self-reliance (1841-1844). The growth of the novel form altogether, through the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, was based on depicting individual characters in their journey to maturity and self-understanding as they find their place in the world—or their failure in that endeavor.

This is the kind of person suited for liberty, self-government, and a limited state, allowing the widest scope for individual freedom and flourishing and doing good for others. When was all that replaced with embracing some collective identity, asserting personal and collective victimization, and demanding that others deemed victimizers deliver boons to us. Allowing ourselves to be shaped by narratives of envy, hatred, and revenge, we can be controlled by ignorant persons wielding the authority of the state.

But in answer to my opening question, whatever happened to the good ideas that arose in the counterculture, the answer is, they are still here, and can be seen in many places, among them Academic Questions. The authors in this issue understand human nature as it is and stand against the irrational currents coursing through contemporary academic and intellectual life.

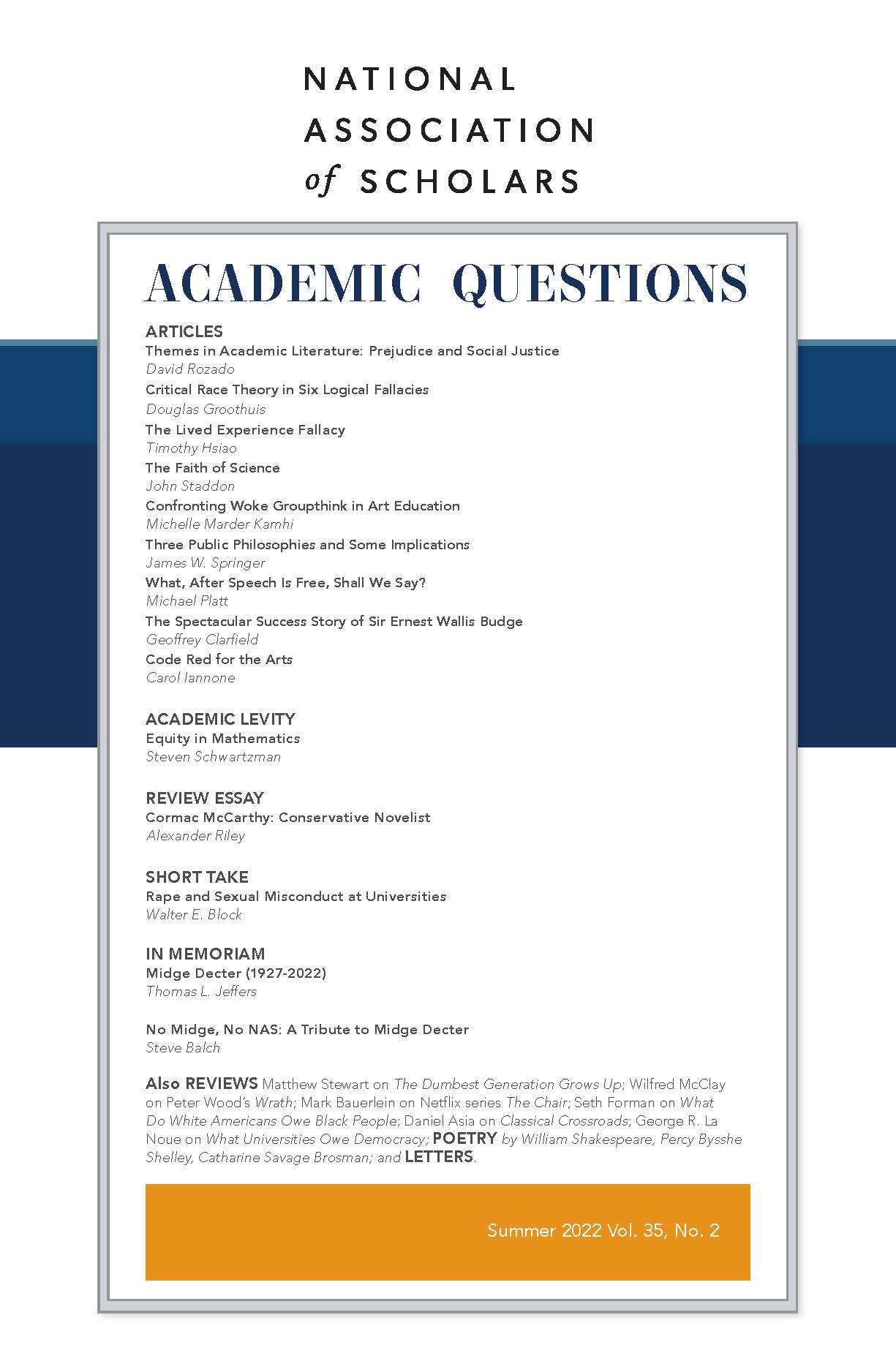

—"Themes in Academic Literature: Prejudice and Social Justice”

David Rozado shows how the scholarly literature of recent decades has been defining justice down and prejudice up, among other spurious endeavors.

—"Critical Race Theory in Six Logical Fallacies”

Douglas Groothuis exposes the weaknesses of critical race theory for those who can still think logically.

—"The Lived Experience Fallacy”

Timothy Hsiao strikes another blow for reason against the nihilism of narcissism.

—"The Faith of Science”

John Staddon lays out some plain facts about science. It is not a substitute for religion, but pursued properly it can build character.

—"Confronting Woke Groupthink in Art Education”

Michelle Marder Kamhi records her online efforts to talk some common sense with contemporary art professors who have evidently lost theirs.

—"Three Public Philosophies and Some Implications”

James W. Springer presents three philosophies of public order that have alternated and held sway in the last five hundred years: hierarchical, civic, and collectivist. Which is best?

—"What, After Speech Is Free, Shall We Say?”

Michael Platt has much good to say.

—"The Spectacular Success Story of Sir Ernest Wallis Budge”

Geoffrey Clarfield takes the occasion of a biography of Budge to explain how he facilitated Western fascination with Ancient Egypt and the Near East.

— “Code Red for the Arts”

Carol Iannone

The Red Violin is a film extolling the transcendent powers of art, I argue.

—"Equity in Mathematics”

Steven Schwartzman shows that he who thinks rationally can also think humorously, and we add a new category of articles, Academic Levity.

—"Cormac McCarthy: Conservative Novelist”

Alexander Riley argues for a conservative streak in the popular novelist prone to graphic violence and dark dystopias in this Review Essay.

—"Rape and Sexual Misconduct at Universities”

Walter Block raises some gratifyingly sensible doubts about the capacity of university faculty to handle sexual harassment cases in this Short Take.

—In Memoriam

Steve Balch, in "No Midge, No NAS: A Tribute to Midge Decter," and Thomas L. Jeffers, in "Midge Decter (1927-2022)," offer appreciations of the godmother of the NAS.