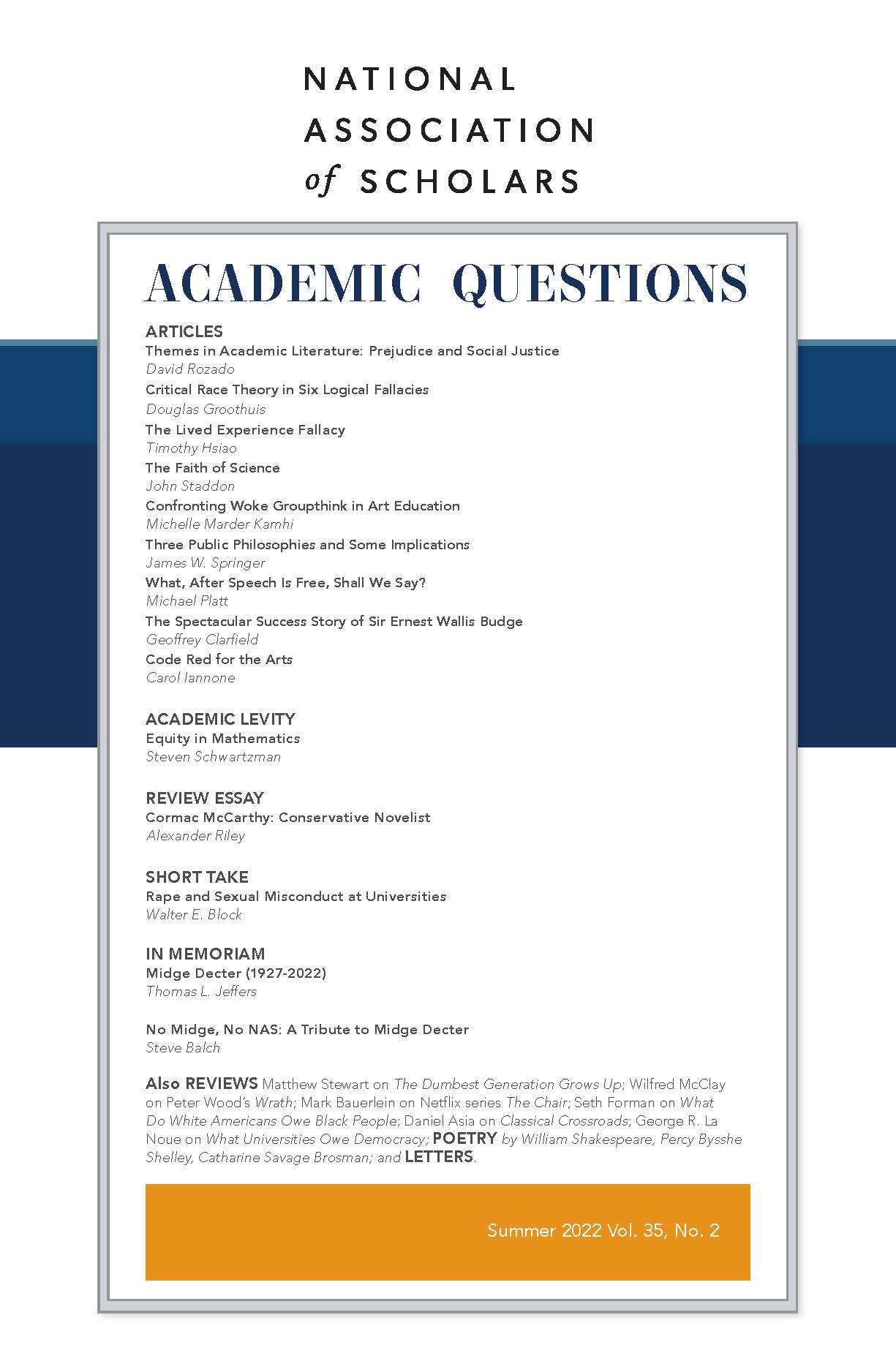

The Chair, a limited streaming television series, Netflix.com, 2021, 1 Season.

Mark Bauerlein is professor emeritus of English at Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322; [email protected]. His latest books are The Dumbest Generation Grows Up: From Stupefied Youth to Dangerous Adults (Regnery, 2022); The State of the American Mind: 16 Leading Critics on the New Anti-Intellectualism, co-edited with Adam Bellow (Templeton, 2015); and The Digital Divide: Arguments for and Against Facebook, Google, Texting, and the Age of Social Networking (Jeremy P. Tarcher, 2011). Bauerlein last appeared in these pages with his article “The Few, the Proud, the Profs.” in the spring of 2021.

The universe of the academic department is so eccentric, overanxious, and implosively familial that people who’ve never been there can’t easily imagine what something as common as a committee meeting is really like. Give credit, then, to the Netflix series The Chair for astutely catching some of the wacky nuances and abiding tensions of professorial reality. We have six episodes so far, a rich cast of characters, plausible confrontations, accurate citations of criticism (Harold Bloom, feminists on Melville’s wife-beating, CRT, etc.), and the nicely insular setting of a small liberal arts college. There is even an insufferably cheery young Title IX administrator in cut-off jeans who has no sympathy for the aged female Chaucerian who has come to complain about an office move. But for all the earnestness, the show can’t break free of the most commonplace identity politics, and the moral instruction of this slice-of-academic-life drama is all too predictable and tiresome.

The show follows the new head of the department, an Asian American woman of moral scruple and progressive belief, as she pilots the English department through student complaints, “dead wood” faculty who won’t retire, a fractious professor-boyfriend who’s also a famous writer, a delicate tenure case, and brand-conscious administrators. Crises arise faster than she can handle them. Her first words to colleagues raise a real problem—English enrollments have plummeted—and the dean tells her the same thing and presses her to get rid of dinosaurs in the department who have high salaries and whose classes are nearly empty. (The dean rightly points out that if the department doesn’t have “butts in seats,” she can forget about much support.)

The rising star is an African American woman with scholarship in PMLA and full classes (one course: “Sex and the Novel”), now up for tenure and courted by the Ivies. Our chair doesn’t want to lose her. What makes it worse is that the chair publicly appoints her to deliver an annual honorary lecture, but higher-ups overrule her and instead invite X-Files actor David Duchovny, who has an MA in English from Yale. This incenses the chair. Another headache: the writer-prof gets a little too performative one day in class, making a Nazi salute when speaking of fascism and the war. Some kids in the room film it with their phones, circulate it, and inspire undergrad complaints, donor phone calls, and bad press. When he stands before the kids in a scene just like Professor Christakis on the Yale quad years back, she ends up getting drawn into their accusations.

That’s the situation. The chair herself spends most of her time frustrated and aggrieved. Her efforts mostly fail. She induces the black professor to team-teach with one of the dinosaurs, knowing she needs his tenure vote, and the class (when he takes the lead) falls flat. The writer-prof, who also baby-sits her child, won’t play the apology game well in spite of her coaching and no matter how many times students and administrators indict and manipulate him. Students push her to sign a petition objecting to a teacher-of-color in another department failing to win tenure, which the chair readily signs without knowing anything about the case, but her compliance earns her no trust from the kids. The dean likes her, but he’d boot her in a second if she jeopardized the Pembroke image or screwed up his budget.

The situations are wholly familiar to people who’ve been in the ranks over the decades. How strange it is, therefore, that so much of the drama turns on conceptions that are thirty-plus years behind the times. The show tries to be au courant, but it relies upon identity tensions that have no existence behind the ivy-covered walls. At one point, for instance, when the chair and the black professor grumble over the old stick-in-the-mud with whom she must share the podium, the professor mutters with the full conviction of righteous grievance about how those stuffy white guys have been able “to rule the profession for the last forty years.” I presume that every living being reading this review knows that the “rule” of traditionalist white males who dislike feminism and theory, as this hoary fellow does, ended sometime in the late twentieth century.

We have many remarks, too, on female professors fighting for equality, the patriarchy still not entirely overturned—a viewpoint quickly dispelled by a tally of English faculty at the top 200 schools in the country. Females make up 48 percent of the English professorate in the U.S.1 And the idea that a black female with an article in the discipline’s flagship journal and classes packed with adoring students need worry about tenure at this small institution is beyond absurd. In reality, the caring solicitousness tendered her by the chair would be echoed by everybody on campus.

As for the dinosaurs in the department, the show presents them as lost and befuddled, unable to relate to students and perplexed by the innovative stuff that has come along since their New Criticism days. The chair herself is a herald of the new and the radical, at one point chiding an old fogy for not bringing CRT and feminism into his work, at another time berating Duchovny for his ignorance of affect theory, ecocriticism, CRT, gender theory, and digital humanities, all of which have “moved the discipline forward.” In truth, however, the Old Guard weren’t so obtuse, and the Young Hotshots not so brilliant and inscrutable. The former knew very well what happened to them, and a lot of them were eager to retire, not to hang on.

Something must be said, too, about this conceit of “advance.” From what I can tell, the show fully endorses the idea that identity studies have produced a breakthrough in academic thinking, an opening and discovery that has raised our understanding of expression, literature, tradition, and the past. The traditionalist classrooms at Pembroke are, indeed, a drag. The few students who attend sleep through the presentations. Meanwhile, cutting-edge classes are boisterous and stimulating. Melville’s “whiteness” excites the kids, we are led to believe, and it calls forth a precious truth that the old textual analysis obscured. The implication is that if the stuffed-shirts would get out of the way and let the identity theorists loose, English would recover. Students would come back. “Let’s f___ing shake this place up!” the chair exhorts.

We have a sorry dramatic irony here, though the creators of the show are as incognizant of it as the chair. For the fact is that theory and identity teaching and research have dominated literary studies for a long time. Queer Theory exploded in the late-80s and was thoroughly mainstream in the quarterlies by 1995. The ecocriticism the chair mentions also dates from the ‘80s, and gender theory, too, while feminism in literary studies started in the ‘70s. This attribution of novelty is way off, a cliché, a self-congratulatory one. One wants to respond to the chair, “Do you know how stale all this is?”

The possibility that enrollments have fallen, at least in part, precisely because of the identity politics here extolled never comes up in the story. By sticking with identity-studies-are-avant-garde instead of longstanding-routine, the writers preempt that notion. We have a version of “socialism has failed because it’s never been really tried.” Here, it becomes “English is failing because too many oldsters haven’t kept up.” As the chair announces early on, she aims to “bring Pembroke into the twenty-first century.”

How much more interesting The Chair would have been if it had opened the prospect—the mere prospect—of identity politics damaging English, not advancing it. The students militating against the Nazi-salute professors are little monsters, and the scenes reveal them in all their righteous arrogance, but the script never hints at what identity politics are doing to them. That would be a compelling development. A nice anagnorisis scene would have the chair realize that the identity-anger of the students might have a source in the unctuous attentiveness she showers on the black professor. It would help, too, if the black professor were touched by a little academic corruption as are all the others, instead of having such a noble, sterling character that rises above it all.

But, of course, that would be to break the progressive mold, to give up on doing ideological work of a leftist kind. Netflix can’t go there.

1 “English Professor,” Zippia.com, Demographics and Statistics In The U.S., https://www.zippia.com/english-professor-jobs/demographics/.

Image: Eliza Morse/Netflix