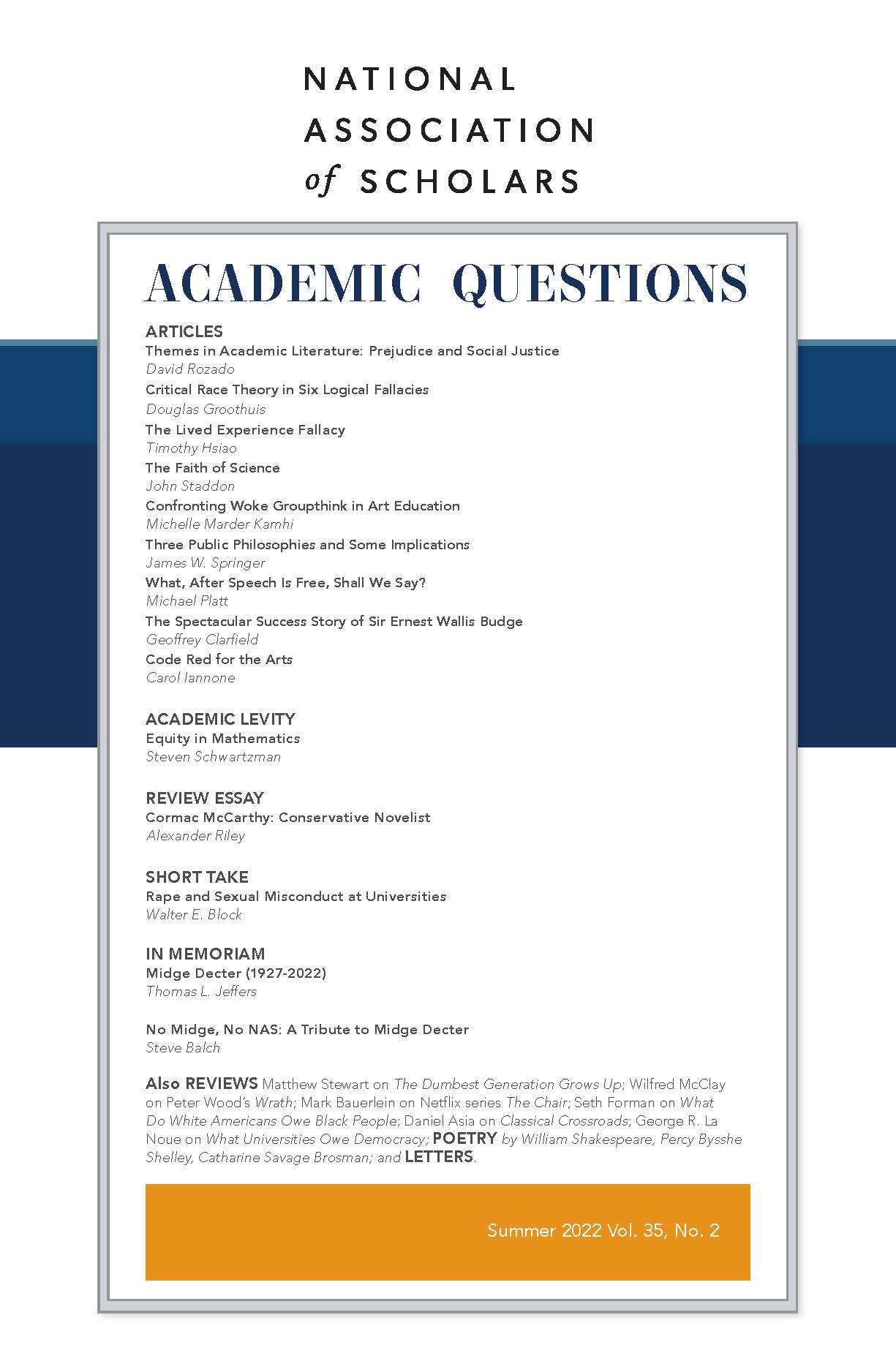

Classical Crossroads: The Path Forward for Music in the 21st Century, Leonard Slatkin, Amadeus, 2021, 238 pp., $23.49 hardcover.

Dan Asia is an American composer whose work ranges from solo pieces to large scale multimovement works for orchestra and includes six symphonies. Since 1988, Asia has been Professor of Composition and head of the Composition Department at the University of Arizona in Tucson; [email protected]. He wrote “The University-Industrial-Woke Complex” for our Fall 2021 issue.

Written during the Covid-19 pandemic when the arts were closed down, Leonard Slatkin’s book, Classical Crossroads, is filled with suggestions for those in the conducting field, both current practitioners and future aspirants. It also takes a wide angle view of the problems classical music faces in the twenty-first century, from repertoire to the size of orchestras, to the length of a music season, music education, funding, and ways to increase minority representation in both orchestras and audiences.

After a brief introduction, the book is laid out in the traditional symphonic form of four movements and then a coda. Each brief subchapter is a riff in the larger scheme of laying out various ideas about music. One could also call it a fantasy on the nature of music in the twenty-first century, what Slatkin describes as a difficult place for classical music. Classical music is also sometimes referred to as “art music,” a music that has a higher calling than pop, and that has certain attributes: it has a long and venerable history; it is mostly in written form; it has a performance tradition; and it is talked about—which is to say, it matters. In the West, art music has developed over time to include polyphony and harmony, which are, as Charles Murray has described, meta-ideas, which changed our concept of the medium or art form. This is in fact why Western classical music has conquered the world, even if only through its popular form. The central focus here is the orchestra, as it has been one of the primary institutions of expression for classical music for the last 250 years or so. It has experienced development and growth over this period, having started with numbers of perhaps twenty-five to often over 100, and starting with string and wind instruments to now include brass, keyboards, and percussion.

Slatkin is primarily a conductor, although his biography also states that he is a composer, author, and educator. All conductors are by definition educators, which is to say their job is to bring the musicians under their direction into unanimity of the interpretation of the musical works being performed. Maybe unanimity is too strong a word. It is better to say that conductors bring many personalities to a common approach and sensibility, where all of those individual capabilities are harnessed for a common artistic good. The conductor may or may not engage in specific educational activities, such as talking about the music or explaining it to those who will hear it. When they do, they help the audience decipher, or experience, the music better. The story of Robert Schumann is pertinent here. Once asked to explain one of his pieces, he simply played it again. Music is best understood within its own medium. However, a guided listening experience does not hurt, and this is precisely what the good musical educator provides the listener.

Slatkin begins with a look at what he has spent most of his life doing, conducting orchestras. He presents Richard Strauss’s comments on conducting and then adds his own. One might think that these comments would be high-minded, but they are not. They are exceedingly practical. It is the hope of every conductor that his performances will lead to the audience’s pleasure, if not elevation. To achieve this effect requires certain simple truths. For Strauss: “If you think the brass are not strong enough, tone them down two points further.” For Slatkin: “Do not talk too much”; “Make sure the music stand is at the correct height.” In regard to orchestral personality, while acknowledging that orchestras now sound increasingly similar, he likes and hopes for the continued idiosyncrasies of orchestras in different localities and countries. These differences display a sense of history of musical approach and understanding, something to be held in high regard. The size and quality of a concert hall makes a difference in the musical experience. “We want to foster that awe that comes from the child who sees the hall for the first time . . . we want that attention to turn to the world of sound, perhaps soliciting not only wonder, but also inspiration.” In the chapter “On the Theater,” Slatkin mentions his short time working in the theatre, i.e. opera, and offers that he thinks Broadway shows like Carousel, My Fair Lady, and West Side Story are just as “difficult and complex as any written for the stage and pit.” Therefore, “it is impossible for me to make a case that musical theatre is a lesser form of art than any of the others that grace the stage.” This is a somewhat fatuous comment. There is a reason that Leonard Bernstein kept trying to write operas and symphonies. He recognized the difference between entertainment and art. The former is all about the listeners’ experience and how it affects them. The latter is about the musical object itself, and its wonderous content and meaning.

In “On Nationalism,” Slatkin makes the case for hiring more American conductors, which would also result in the performance of more American music. He mentions the fine conductors of his generation and those just younger—Gerard Schwarz, Michael Tilson Thomas, Marin Alsop, and Robert Spano—who made it part of their duty and pleasure to explore and program different aspects of the present American compositional scene. He decries that this is no longer happening. American orchestras and their mostly foreign conductors feel no responsibility to the American musical legacy and its current manifestations, and they feel no obligation or desire to present it to their patrons. This is a shame, as there is so much wonderful music of the twentieth century, and most of it completely unknown to American audiences. Historical amnesia in music, or any other artistic or intellectual sphere, is not good. Neither is a lack of audience engagement with the present production of musical art, which helps us to see and know who we are.

No book appearing at this time could avoid the question of diversity, and Slatkin does not. From the middle of the last century to now all orchestral auditions have taken place behind a screen to avoid even the hint of discrimination. In this time, the composition of orchestras has dramatically changed. Most are at least half composed of women, and Asians have replaced what was formerly a predominance of Jews. Orchestras are now completely integrated with what were considered marginalized groups only a generation ago. Discrimination is gone. “In a way, the screen now represents a bit of an insult to those who are making the decisions as to who will join the orchestra. Do we really believe that musicians of today cannot come to a fair conclusion irrespective of the candidate’s gender and race?” In his comments, Slatkin does not refer to blacks or Latinos as underrepresented categories. This would apparently be too transparent and problematic, as he would then have to ask the question of why these groups are not well-represented in orchestras. He wanly does so, by suggesting that early educational activities in these communities on the part of orchestras and schools might help solve this problem.

Throughout his career, Slatkin promoted the music of living composers. He did this to distinguish himself from other, more staid conductors who only performed the established repertoire. But he followed this path also because he loves this music, and understands that the canon must be invigorated and replenished with the new music of composers who are writing in the present and creating music for, and reflective of, this time. The canon should be always expanding. As he mentions, it is also the conductor’s job to constantly discover what came before, either acknowledged or hidden, and is waiting to be revealed. Such a scenario has included, for an American conductor like James Conlon, finding those voices that were silenced or muffled by the Holocaust and its legacy. Haas, Klein, Ullman, and the recently discovered Weinberg, are all composers who were interned at the concentration camp of Terezin, with only the last surviving the war, and their music is now being performed and recorded. But such revelation and discovery also occurs in the re-engagement with each encounter with a piece of the past, or with the music of a young composer who just knows that he could be the next Beethoven if someone would only give him a chance; who knows that old music is truly alive again in any new performance, and that the brand new work might—just might—be the next great symphony. All this music must be realized in performances that engage our present sensibilities, so that it has meaning for us. Otherwise, the performance is a sterile and non-communicative experience. For what Slatkin says about arts education, also applies to the arts, but particularly music: “[It] satisfies our hearts, minds, and souls.”