In this article I offer new evidence about something readers of Academic Questions already know: The political registration of full-time, Ph.D.-holding professors in top-tier liberal arts colleges is overwhelmingly Democratic. Indeed, faculty political affiliations at 39 percent of the colleges in my sample are Republican free—having zero Republicans. The political registration in most of the remaining 61 percent, with a few important exceptions, is slightly more than zero percent but nevertheless absurdly skewed against Republican affiliation and in favor of Democratic affiliation. Thus, 78.2 percent of the academic departments in my sample have either zero Republicans, or so few as to make no difference.

My sample of 8,688 tenure track, Ph.D.–holding professors from fifty-one of the sixty-six top ranked liberal arts colleges in the U.S. News 2017 report consists of 5,197, or 59.8 percent, who are registered either Republican or Democrat. The mean Democratic-to-Republican ratio (D:R) across the sample is 10.4:1, but because of an anomaly in the definition of what constitutes a liberal arts college in the U.S. News survey, I include two military colleges, West Point and Annapolis.1 If these are excluded, the D:R ratio is a whopping 12.7:1.

Why Political Homogeneity Is Troubling

Political homogeneity is problematic because it biases research and teaching and reduces academic credibility. In a recent book on social psychology, The Politics of Social Psychology edited by Jarret T. Crawford and Lee Jussim, Mark J. Brandt and Anna Katarina Spälti, show that because of left-wing bias, psychologists are far more likely to study the character and evolution of individuals on the Right than individuals on the Left.2 Inevitably affecting the quality of this research, though, George Yancey found that sociologists prefer not to work with fundamentalists, evangelicals, National Rifle Association members, and Republicans.3 Even though more Americans are conservative than liberal, academic psychologists’ biases cause them to believe that conservatism is deviant. In the study of gender, Charlotta Stern finds that the ideological presumptions in sociology prevent any but the no-differences-between-genders assumptions of left-leaning sociologists from making serious research inroads. So pervasive is the lack of balance in academia that more than 1,000 professors and graduate students have started Heterodox Academy, an organization committed to increasing “viewpoint diversity” in higher education.4 The end result is that objective science becomes problematic, and where research is problematic, teaching is more so.

The Nonconforming Few

A few liberal arts colleges are outliers and do not conform to the standard liberal slant. One, Thomas Aquinas, has thirty-three full-time faculty and all are Republican. The two military colleges in my sample, West Point and Annapolis, have D:R ratios of 1.3:1 and 2.3:1. Although it is debatable whether military colleges are liberal arts colleges, U.S. News’s inclusion of them in the liberal arts category is fortuitous because they offer evidence that when colleges provide supportive environments, intellectual diversity is achievable. There are other exceptions, such as Claremont McKenna, which adopted a viewpoint diversity strategy early in its history, and Kenyon, which is one of a few of the top-ranked liberal arts colleges located in a predominantly Republican state and which did not become coed until 1969.

Thomas Aquinas and St. John’s, another college with above average Republican representation, have emphasized interdisciplinary teaching and downplayed the publish or perish imperative, which Daniel B. Klein and Charlotta Stern have argued contributes to left-oriented groupthink.5 The exceptions to the Democratic-only rule indicate that institutional factors and discrimination might be key reasons for political homogeneity in the liberal arts colleges.

Trend toward Homogeneity

Noah Carl shows that in Britain the trend has been toward increasing leftward affiliation.6 The same has been true in the U.S. More than a decade ago, Stanley Rothman and colleagues provided evidence that while 39 percent of the professoriate on average described itself as Left in 1984, 72 percent did so in 1999. They find a national average D:R ratio of 4.5:1.7 More recently, Anthony J. Quain, Daniel B. Klein, and I find D:R ratios of 11.5:1 in the social science departments of highly ranked national universities.8 This study finds a D:R ratio of 10.4:1 across all liberal arts departments if the military colleges are included and 12.7:1 if the military colleges are excluded.

Data

The fifty-one institutions in this study are among the top sixty-six-ranked U.S. News and World Report national liberal arts colleges for 2017. The data are limited to the fifty-one colleges located in twelve states that host at least one of the top sixty-six colleges and that make voter registration information public.9 One college, the United States Air Force Academy, does not provide a full faculty list online and refused to comply with my Freedom of Information Act request for a complete faculty list.

To obtain data, I consulted the online website of each college and identified the full-time, Ph.D.–holding professors in each department. I limited the sample to full-time, Ph.D.–holding tenure-track faculty who are identified as full, associate, or assistant professors. Thus, I omitted short-term-contract, adjunct, visiting, and emeritus professors. A research assistant helped with the Pennsylvania colleges.

I began work in February 2017 and finished in September 2017. The sample, which includes individuals not registered, amounts to 8,688 professors in fifty-one institutions. In three institutions, St. John’s, Thomas Aquinas, and Sarah Lawrence, I was unable to determine academic ranks, so ranks are missing. In St. John’s and Thomas Aquinas I was unable to determine fields of specialization, so the academic field was omitted from these two colleges.

Nonregistration

Not all professors register to vote. In 2016, Quain, Klein, and I find that 29.7 percent of our sample of professors at top-tier social science departments were unregistered, but that 15.7 percent of this group were so classified because the presence of other people with the same name on voter registration rolls made determining registration impossible. 10 In this study, I find that a lower proportion—23.4 percent— of the sample is unregistered.

It is not possible to accurately measure the political affiliations of professors registered as “independent,” “no affiliation,” or “other,” whom I lumped together in a category I called “No Party” or “NP.” Since Gallup found in 2014 that 47 percent of Democrats and 46 percent of Republicans say that a third party is needed, there seems little reason to believe that one party or ideology is more strongly associated with non-affiliation. 11 There is suspicion of the two-party system on both Left and Right.

I needed to make a number of judgment calls with respect to the assignment of faculty to neighboring fields. For instance, I assigned biologically oriented neuroscience faculty to biology and psychologically oriented neuroscience faculty to psychology. I aggregated the studies fields (gender studies, Africana studies) into one category, which I call “interdisciplinary studies.” As well, I aggregated the professional fields (accounting, business, nursing) into one category called “professional.”

Only 101 professors in the sample are registered with minor parties. Since they are only 1.2 percent of the sample of 8,688 professors, I omitted them from most of the analyses.

Findings

D:R Ratios by Field

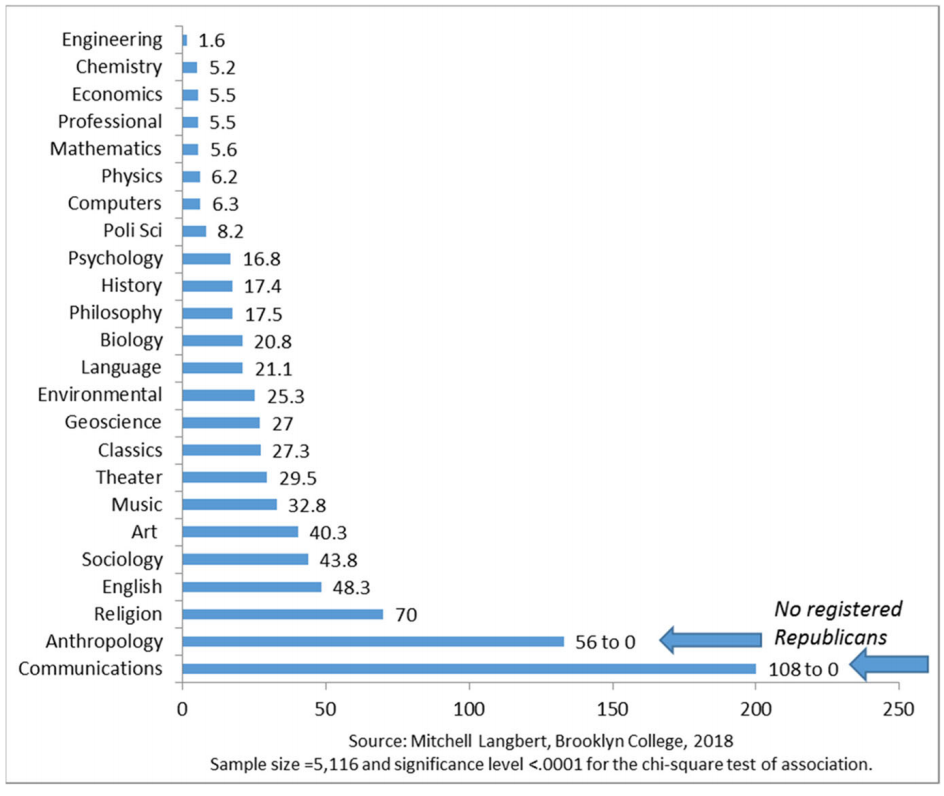

Figure 1 illustrates the sharp differences across the departments or fields in the liberal arts colleges. The D:R ratios range from 1.6:1 for engineering to 56:0 and 108:0 for communications and interdisciplinary studies.

Number of Democratic Faculty Members for Every Republican in 25 Academic Fields

The STEM subjects, such as chemistry, economics, mathematics, and physics, have lower D:R ratios than the social sciences and humanities. The highest D:R ratio of all is for the most ideological field: interdisciplinary studies. I could not find a single Republican with an exclusive appointment to fields like gender studies, Africana studies, and peace studies. As Fabio Rojas describes with respect to Africana or Black studies, these fields had their roots in ideologically motivated political movements that crystallized in the 1960s and 1970s.12

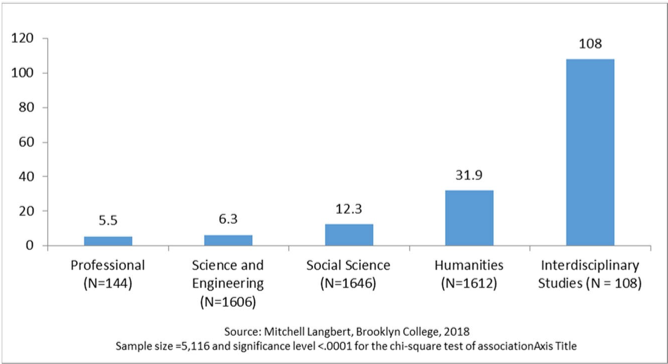

Figure 2 gives a picture of how the broad liberal arts fields compare with respect to political affiliation. The professional field has the least extreme (but still unbalanced) D:R ratio while ideologically rooted interdisciplinary studies has the most extreme. The hard sciences are more balanced than the social sciences and the humanities.

Number of Democratic Faculty Members for Every Republican in Five Broad Fields

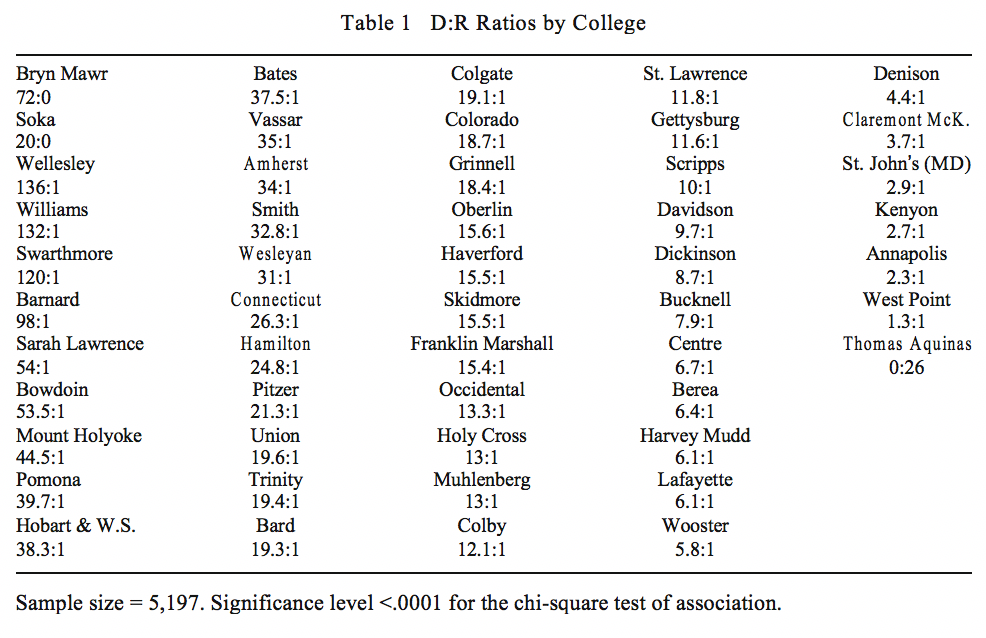

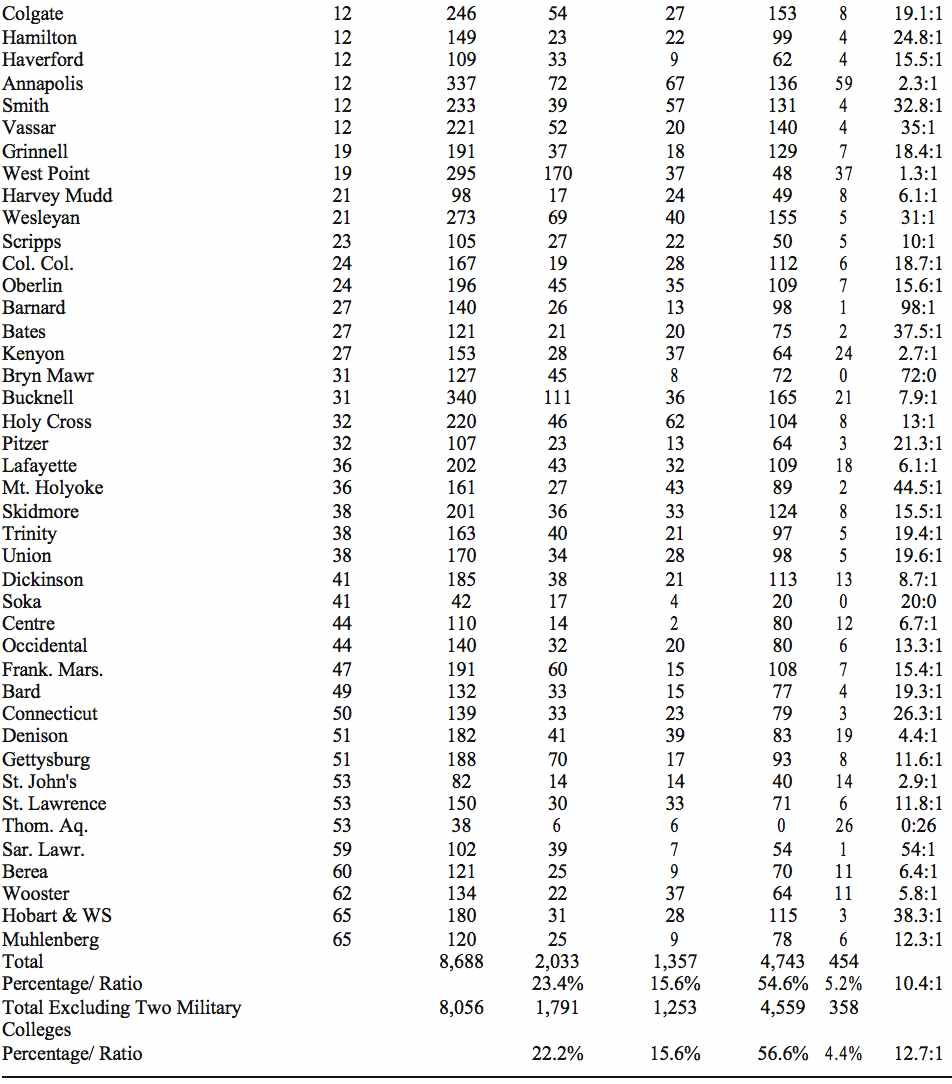

D:R Ratios by College

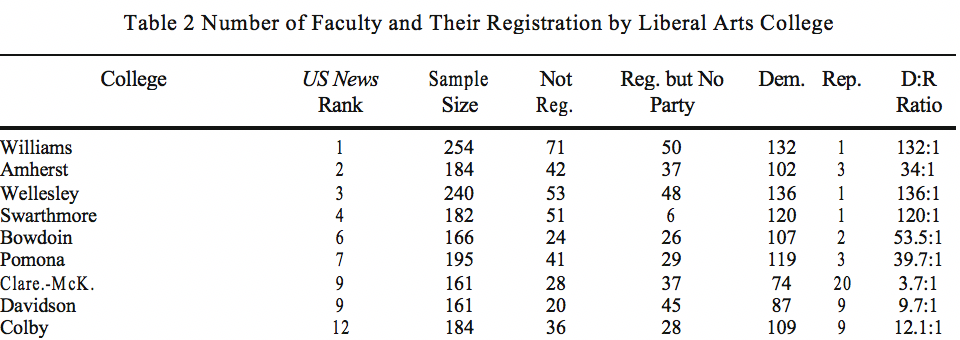

Table 1 lists the Democratic-to-Republican ratio of each college in the sample. I could not find any full-time, Republican-registered faculty at Bryn Mawr and Soka, and I could not find any full-time, Democratic-registered faculty at Thomas Aquinas. For example, I identified 254 full-time, Ph.D.-holding professors at Williams. Of these, 132 are registered Democratic, and one is registered Republican, so the D:R ratio is 132:1. Since not all colleges offer all fields, the ratios are influenced by the majors offered and by demographic factors, such as the proportion of the faculty that is female.

In order to get a sense of how far away from employing zero Republicans the colleges are, I performed t-tests to determine the number of colleges for which zero falls within the margin of error from the observed proportion of Republicans.13 In other words, I wanted to determine the number of colleges for which the proportion of Republicans is not statistically different from zero. For fifteen of the colleges, zero falls within the margin of error, so the proportion of Republicans can be said to not significantly differ from zero. In an additional five colleges, the lower confidence interval just equals zero at three decimal digits. Thus, for twenty of fifty-one colleges, or 39.2 percent, the proportion of Republicans does not significantly differ from zero.

Table 2 gives the raw numbers from which I computed the D:R ratios by college. Thomas Aquinas and St. John’s College rely on an interdisciplinary pedagogical approach and do not indicate departments. I found 808 departments that do not employ a single Republican, and I found only 225 departments that do. Thus, 78.2 percent of departments do not employ a single Republican while 21.8 percent do.

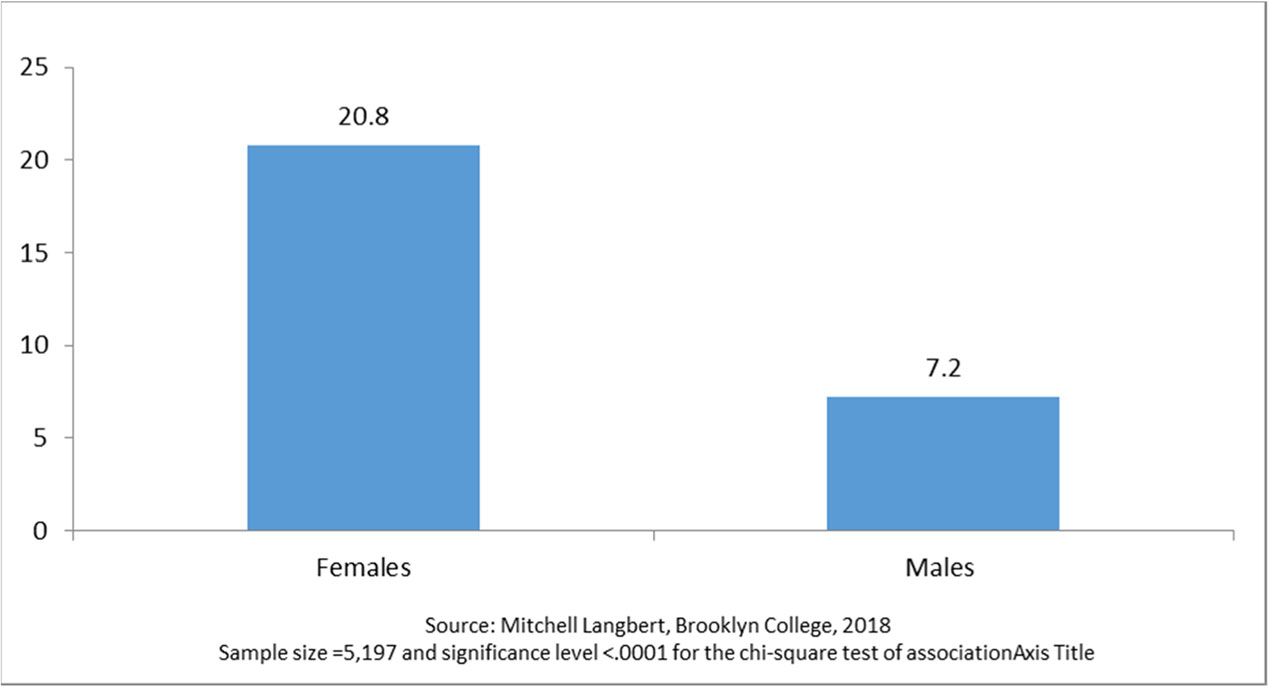

Gender and Political Homogeneity

Figure 3 shows that the D:R ratios among the elite liberal arts faculty are 20.8:1 for females and 7.2:1 for males. When the two military colleges are excluded, the ratios are 25.2:1 for females and 8.7:1 for males. Langbert, Quain, and Klein find a similar gender imbalance in elite research universities: 24.8:1 for females and 9.0:1 for males.14

Number of Democratic Faculty Members for Every Republican by Gender

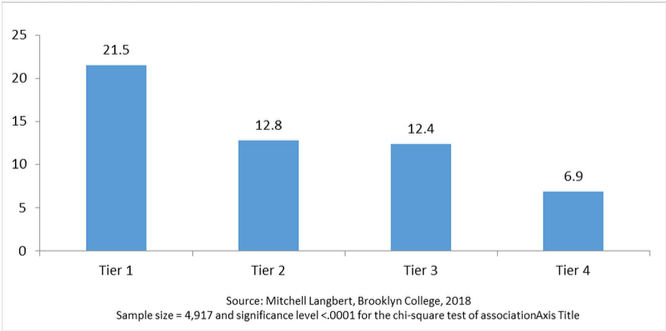

U.S. News Rank and Homogeneity

Since the days of C.B. Spaulding and H.A. Turner, Burton R. Clark, and Everett Carll Ladd Jr. and Seymour Martin Lipset, researchers have noticed that elite colleges have tended to lean left.15 In this sample, when I exclude the two military colleges and break the remaining ones into quartile tiers based on U.S. News rank, that pattern is sustained (see Figure 4).

Number of Democratic Faculty Members for Every Republican by US News Rank (49 Non-military Colleges)

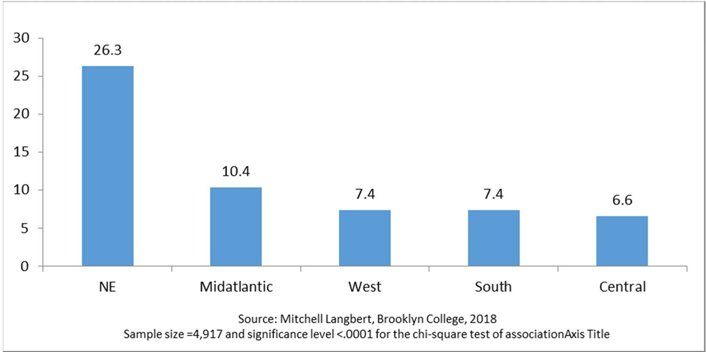

Region and Homogeneity

Samuel J. Abrams has pointed out that colleges in New England tend to lean further to the left than other colleges.16 Figure 5 shows the D:R ratios for the non-military colleges in five sets of states: New England and New York (NE); Pennsylvania and Maryland; California and Colorado; Kentucky and North Carolina; and Ohio and Iowa. As Abrams predicts, the ratio is highest in New York and New England

Number of Democratic Faculty Members for Every Republican by Region (49 Non-military Colleges)

Given regional differences, it seems likely that state political variables will be associated with faculty political affiliation, yet little work has been done in this regard. Public choice theory predicts that compact organizations like colleges and academic fields will function effectively as lobbies.17 David A. Tandberg suggests that both state government control and state mass opinion might influence political attitudes in higher education.18 Tandberg cites research indicating that the governor is the most important influence on higher education policy.

I used two measures: the Cato Institute ratings of governors and the Gallup ratings of state politics for 2016–2017.19 The Gallup ratings indicate whether public opinion in the state is strongly Democratic or Republican, leans Democratic or Republican, or is competitive. For the Cato measure I took the mean of their 2010 and 2016 rankings because a number of gubernatorial administrations have recently changed.

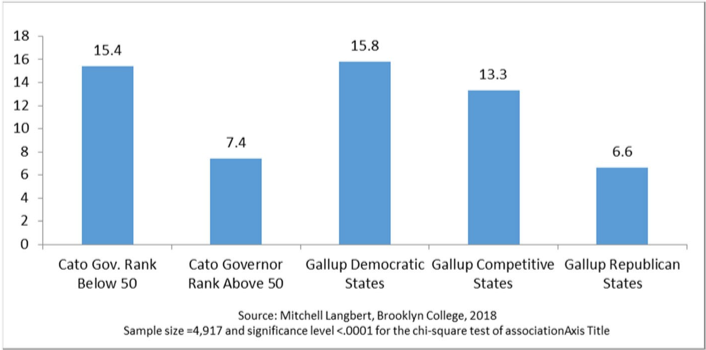

Figure 6 shows that there are significant associations between (a) Gallup ratings of public opinion and Cato governor ratings and (b) faculty partisan affiliation. In Gallup Republican states, the D:R ratio is 6.6:1 while in Gallup Democratic states the ratio is 15.8:1. In states with Cato governor ranking above 50, indicating a relatively free market orientation, the ratio is 7.4:1 while in states with Cato rankings below 50, the Democratic-to-Republican ratio is 15.4:1. These differences are statistically significant.

Number of Democratic Faculty Members for Every Republican by Politics of State (49 Non-military Colleges)

Conclusion

In this paper I find that D:R ratios among fifty-one of the top sixty-six U.S. News-ranked colleges average 10.4:1., Excluding Annapolis and West Point raises the ratio to 12.7:1. This compares with a national D:R ratio of 1.6:1 for people who have some graduate school experience.

Some STEM fields come close to the baseline national average of 1.6:1; potentially ideologically linked fields, especially the interdisciplinary studies fields, do not. Thus, the D:R ratio for engineering is 1.6:1 while for the interdisciplinary studies fields it is 108:0.

Institutional factors at the state government level as well as at the individual college level may play some causal role. Professors in more Democratic states, especially in New York and New England, are more often affiliated with the Democratic Party than in other states.

Since the 1960s, a few liberal arts colleges have not conformed to the homogenizing trend, and these demonstrate that institutional characteristics, at a minimum, contribute to faculty political affiliation in liberal arts colleges. Thomas Aquinas is all Republican, and the two military colleges in my sample, West Point and Annapolis, have D:R ratios of 1.3:1 and 2.3:1. Studies that focus on grand means ignore the association of affiliation rates with institutional characteristics.

These findings suggest important implications for research and policy. For research, a coherent causal model of the imbalance in political affiliation in colleges requires that statistical models integrate institutional effects with individual faculty characteristics. For policy, if political homogeneity is embedded in college culture, attempting to reform colleges by changing their cultures seems a very tall order. The solution to viewpoint homogeneity may lie in establishing new colleges from the ground up, rather than in reforming existing ones.

Mitchell Langbert is an associate professor of business management at Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, NY 11210; [email protected]. The author thanks the Searle Freedom Trust for its financial support, Brooklyn College for a year of faculty leave, and Glenda R. McGee for research assistance. The author also thanks James Dalton, Ward Elliott, Bruce Fleming, J. Philip Gleason, Lee Jussim, Daniel B. Klein, and David O’Brien for institutional background and other information.

1 David W. Breneman “Are We Losing Our Liberal Arts Colleges?” AAHE Bulletin 43, no. 2 (October 1990): 3–6, available at http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED339260.pdf) defines liberal arts colleges as residential colleges that award the B.A. degree, enroll full-time students between 18 and 24, enroll fewer than 2,500 students, and limit the number of majors to twenty in the arts and sciences. In contrast, Robert Morse, Eric Brooks, and Matt Mason, in “How U.S. News Calculated the 2018 Best Colleges Rankings,” U.S. News and World Report, September 11, 2017, https://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/how-us-news-calculated-the-rankings, define liberal arts colleges as colleges that focus almost exclusively on undergraduate education and award at least 50 percent of their degrees in arts and sciences.

2 Mark J. Brandt and Anna Katarina Spälti, “Norms and Explanations in Social and Political Psychology,” in Jarret T. Crawford and Lee Jussim, eds. The Politics of Social Psychology (New York: Routledge, 2018).

3 Lydia Saad, “U.S. Conservatives Outnumber Liberals by Narrowing Margin,” Gallup News, January 3, 2017, http://news.gallup.com/poll/201152/conservative-liberal-gap-continues-narrow-tuesday.aspx; Charlotta Stern, “Does Political Ideology Hinder Insights on Gender and Labor Markets?” in Jarret T. Crawford and Lee Jussim, eds. The Politics of Social Psychology (New York: Routledge, 2018); George Yancey, Compromising Scholarship: Religious and Political Bias in American Higher Education (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2017).

4 Heterodox Academy. “The Problem.” Heterodoxacademy.org, https://heterodoxacademy.org/the-problem/

5 Thomas Aquinas College, “A Liberating Education.” https://thomasaquinas.edu/a-liberating- education/liberating-education”; St. John’s College, “Undergraduate Program,” https://www.sjc. edu/academic-programs/undergraduate; Daniel B. Klein and Charlotta Stern, “Groupthink in Academia: Majoritarian Departmental Politics and the Professional Pyramid,” in Robert Maranto, Richard E. Redding, and Frederick M. Hess, eds., The Politically Correct University: Problems, Scope, and Reform (Washington, DC: AEI Press, 2009): 79–98.

6 Noah Carl, “Lackademia: Why Do Academics Lean Left?,” Briefing Paper. Adam Smith Institute, March 2, 2017, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56eddde762cd9413e151ac92/t/58b5a7cd03596ec6631d8b8 a/1488299985267/Left+Wing+Bias+Paper.pdf.

7 Stanley Rothman, S. Robert Lichter, and Neil Nevitte, “Politics and Professional Advancement Among College Faculty,” The Forum 3, no. 1 (2005), http://www.conservativecriminology.com/uploads/5/6/1/7/56173731/rothman_et_al.pdf.

8 Mitchell Langbert, Anthony J. Quain, and Daniel B. Klein, “Faculty Voter Registration in Economics, History, Journalism, Law, and Psychology,” Econ Journal Watch 13, no. 3 (September 2016): 422–51, https://econjwatch.org/articles/faculty-voter-registration-in-economics-history-journalism-communications- law-and-psychology.

9 Of the 2017 top sixty-six U.S. News-ranked liberal arts colleges, fourteen are located in states that do not release voter registration data.

10 Langbert et al., “Faculty Voter Registration.”

11 Jeffrey M. Jones, “GOP Maintains Edge in State Party Affiliation in 2016,” Gallup News, January 30, 2017, http://news.gallup.com/poll/203117/gop-maintains-edge-state-party-affiliation-2016.aspx.

12 Fabio Rojas, From Black Power to Black Studies: How a Radical Social Movement Became an Academic Discipline (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

13 Robert L. Winkler and William L. Hays, Statistics: Probability, Inference, and Decision, Second Edition (New York: Harcourt School, 1975).

14 Langbert et al., “Faculty Voter Registration.”

15 C.B. Spaulding and H.A. Turner, “Political Orientation and Field of Specialization among College Professors,” Sociology of Education 41:3 (1968), 247–62; Burton R. Clark, The Distinctive College: Antioch, Reed, and Swarthmore (London, UK: Routledge Publishers, 1992); Everett Carll Ladd Jr. and Seymour Martin Lipset, The Divided Academy: Professors and Politics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1975).

16 Samuel J. Abrams, “There Are Conservative Professors. Just Not in These States,” New York Times, Sunday Review, July 1, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/03/opinion/sunday/there-are-conservative- professors-just-not-in-these-states.html.

17 Mancur Olson, The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1984).

18 David A. Tandberg, “Politics, Interest Groups and State Funding of Public Higher Education,” Research in Higher Education 51: 416–50 (2010).

19 Chris Edwards, “Fiscal Policy Report Card on America’s Governors: 2010,” Policy Analysis 668, White Paper, September 30, 2010 (Washington, DC: Cato Institute, 2010), https://object.cato.org/pubs/pas/PA668. pdf; Fiscal Policy Report Card on America’s Governors 2016, October 5, 2016 (Washington, DC: Cato Institute, 2016), https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/edwards_report_card_on_govs_20161004. pdf; Jeffrey M. Jones, “GOP Maintains Edge in State Party Affiliation in 2016.”

Image Credit: Republican? Democrat? Undecided? by Eden, Janie and Jim from NYC // CC BY 2.0