James W. Springer is a retired attorney; [email protected]. He is the co-author with Elizabeth Weiss of Repatriation and Erasing the Past (University of Florida Press 2020). Springer thanks Professor Elizabeth Weiss of the Department of Anthropology at San Jose State University for her comments on an earlier draft of this article. Any errors are the author’s own.

In the last five-hundred years of Western civilization, there have been, broadly speaking, three public philosophies: hierarchical, civil, and collectivist, each of which reflects a different understanding of the proper role of power and authority. The three philosophies are expressed in practice as much as in abstract philosophical discussions, and indeed, the practice of law, politics, and private associations often exhibits the differences better than those abstract discussions. The definition and exploration of these differences will help us to understand the background and context of our current controversies.

By hierarchical, I understand, first, a thought and practice based upon hereditary social classes, which differ in legally enforceable rights, powers, duties, and disabilities, often symbolized by titles and honorifics and informal acts of deference. Rights to own certain types of property, to hold public office, and to vote for public officials are held hierarchically. Secondly, this hierarchy and the entire life of the polity are thought of as based upon and justified by a series of religious communications. If asked why you do it this way, the answer is because God or the gods told us to do it this way.

A hierarchical philosophy of public order is not surprising. Indeed, most of the civilizations of which we have any knowledge have had some version of this philosophy. Certain institutions and practices, inherited from the past and brought together mostly by accident, have made the West’s understanding of hierarchy unique, among them Roman law, Christianity, the tradition of contractual (as opposed to deferential) allegiance derived from Germanic tribal law, and feudalism.

By the seventeenth century, something approaching the modern nation state had appeared in several parts of Europe and state formation was proceeding in the other parts, at the expense of the preexisting empires, principalities, and free cities. At the same time, people began to talk (and write) about “civil society,” and the joint occurrence is not coincidental. Civil society was the mutual association of individuals who recognized themselves as citizens subject to the legitimate and necessary rules of the nation state. Citizens had access to the rules of private conduct for cooperating with each other, such as property, contract, trust, and partnership. Civil society clearly included law, politics, and government, which were its focus, but by implication it extended to various private and voluntary associations, whose exact character was unclear. Economics was the first non-political activity that was clearly reflected upon, and renowned Enlightenment economists such as David Hume and Adam Smith virtually defined the discipline. Non-economic voluntary activity was not the subject of such sophisticated reflection until Alexis de Tocqueville in the nineteenth century. Burke’s tribute to “little platoons” is often remarked upon, but Burke was more of an inspired polemicist than a systematic thinker and his contributions did not generally extend to the voluntary parts of civil society. Tocqueville’s elucidation of the “habits of the heart” and “self-interest rightly understood” was a truly innovative reflection, although the practice had long existed.

The emergence of a collectivist view of public order is harder to trace, although we can see it in the later stages of the French Revolution, when “citizen” had become a term of identity and incorporation (not merely a recognition of a public order), much like “comrade” in the twentieth century. In the collectivist view of things, the most important thing about any human being is not his individuality, his ontological status as a human being, or his mere participation as a citizen of a nation state. The most important quality is his subsumption under a category or grouping which may be race, ethnicity, tribe, nationality, religion, social class, sex or sexual identity, or any other of a number of proliferating categories. It is not in God or Zeus that we live and move and have our being, but rather in our membership in a race or class and only in that membership. Moreover, the various categories are not of equal moral status; some are superior to others. As to why this should be so, there have been a variety of answers. Probably the oldest is that we were chosen by God or the gods or (in its secular forms) that we were chosen by history or evolution. However, the rationale that has been hit upon most recently is that we are victims, that the other category is that of victimizer, and that victims are morally superior to victimizers. The victims realize that they are victims, and this realization fills them with shame, fear, and a fierce resistance to any challenge to their victim status or the legitimacy of their demands. Some ideologies attempt to combine the various rationales, as when it is claimed that the victims are superior spiritually, esthetically, or ecologically to their victimizers. The proper role of public authority, in this view, is not to be neutral as to the various groups or categories, but rather to promote the interests of the more deserving at the expense of the less deserving.

Several qualifications should immediately be noted to the above taxonomy. It consists of three ideal types, in which the motives, values, and understandings that are so often mixed in practice are reduced to pure and unmixed form. Particularly in the nineteenth century, there were intelligent individuals, John Stuart Mill and Matthew Arnold among them, who saw virtues in all three types and attempted to reconcile or at least balance them.

One may strongly prefer one of the three philosophies and yet recognize the subtleties and complications of thought and action when dealing with that most complicated of beings, namely humans. One may strongly prefer the civil philosophy and deplore the hierarchical one and still recognize the paradoxes that complicate his preferences. It may well be that the British royal family serves a valuable purpose in what is otherwise a civil, or increasingly a collectivist, society. To remove the nominal head of state from the clash of electoral politics may be a great benefit, and if so, those who carry out that purpose loyally and gracefully deserve our thanks.

One may disagree strongly with one of the public philosophies, even despise it, and simultaneously recognize that it has an appeal for many people. Even if individuals should not be seen primarily as bearers of a collectivist identity, if enough influential and powerful people take a collectivist view of inner cohesion and outward hostility, collectivism will become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

After having largely abandoned the hierarchical philosophy, we can see some benefits to it that were not apparent in the time of its dominance. It settled the issue of who deserved power and respect in a way that, while arbitrary, had the advantage of clarity and finality and a metaphysical justification. The modern obsession with inequality, and the rage for equality, no matter how vaguely and ambiguously defined, and the accompanying hostility toward the merit principle, even to the point of denying the existence of merit, is one of the unforeseen consequences of the triumph of the civil and collectivist philosophies.

Likewise, the modern search for “meaning” and “spirituality,” with its exuberance of cults, both sacred and secular, borrowed from societies all over the world (Eastern mysticism, Native American sweat lodges) exhibits one of the unanticipated costs of the loss of the religious aspect of the hierarchical philosophy. Few in the West would now assert or explicitly endorse the principle that tout commence en mystique et finit en politique (it all starts in faith and ends in politics) but the abandonment of that principle, however desirable, left many moderns adrift in a world of borrowed cults, secular substitutes for religion, and an anguish that found an outlet in revolutionary and totalitarian politics.

Of all the varieties of collectivism, Marxism has proven to be the most pervasive and persistent. It has furnished a model or template for other forms of collectivism. The idea that Marxism collapsed with the Soviet Union is quite unwarranted. It is probably true that those who have experienced Marxist dictatorships firsthand have a healthy aversion to the doctrine, but even those who have felt its oppressiveness may miss the certainty and simplicity that it gave, and in the freer parts of the world, Marxism has, if anything, increased its appeal. One line of evidence for the idea that Marxism is foundational to collectivism is the frequency with which its sympathizers attempt to combine it with what are, on the surface, very different ideologies. Marxism and Christianity, Marxism and feminism, Marxism and psychoanalysis, Marxism and existentialism are hybrid combinations whose logical contradictions should be apparent to those who profess to construct philosophical systems. Likewise, the contradictions should be obvious in the remarkable synthesis of Marxism with national, ethnic, or even racial ideologies that would have amazed Marx.

At the same time as there is a fashion for ideologies, artifacts, and symbols from ethnic minorities and tribal societies there is a fierce criticism of these fashions as “cultural appropriation” and a demand that the use of such fashions be forbidden or only allowed with the permission of their presumed creators. In practice, of course, cultural appropriation has been going on since the first band of hunters and gatherers noticed that their neighbors had invented something useful. Indeed, the ethnic and tribal artifacts that are so admired are usually based on technologies that were borrowed from other peoples, now viewed as oppressors.

The taxonomy just outlined could be the source of many fruitful inquiries, but one is of particular interest, namely attitudes toward historical and cultural differences. The hierarchical philosophy was based upon Christianity, but accompanied by a deep appreciation for the ideas and institutions of Greek and Roman paganism. Christian authors such as Dante saw nothing wrong with incorporating pagan heroes and villains into their Christian writings. Many worthies struggled to reconcile the two systems, and some (such as Machiavelli) clearly preferred the pagan view of things.

The appearance of the civil philosophy was accompanied by a profound change in the way comparative studies of cultural differences were viewed. There were some dubious philosophical constructions (the state of nature, the social contract) whose relationship to any empirical evidence was uncertain. They are best viewed as myths or parables rather than empirical hypotheses. However, there also appeared descriptive accounts of non-Western cultures far more serious than anything that had appeared before. Also new were classifications and typologies, such as Montesquieu’s, which finally supplanted the Aristotelian classifications and theorizing that had dominated Western thought for two thousand years. These activities resulted in entirely new disciplines, barely prefigured in ancient and medieval times, such as critical historiography, epigraphy, historical linguistics, archaeology, and ethnology. The new findings were expressed in publications, both technical and popular, and in museums open to the public which far transcended the limitations of the private cabinets of curiosities of wealthy individuals.

By the late twentieth century, the process just described had produced an extraordinary knowledge of the world’s cultures that was available to a larger portion of the world’s population than ever before, and it was then that it was challenged and indeed vilified by the philosophy of collectivism. Edward Said’s Orientalism, published in 1975, is conventionally taken as a landmark of this process, and I believe the choice is appropriate. Said’s hostility and resentment toward the study of the urban literate cultures of Asia spread to the study of what were until recently called “primitive” cultures since recast as First Nations or First Peoples or Indigenous Peoples. It has taken the form of accusations of racism and demands that the comparative study of cultures be reoriented toward a favorable, indeed flattering, treatment of First Nations, in which the recitation of unpleasant or merely inconvenient facts is recast as harmful, hurtful assertions that must be suppressed and punished. Activists seek to transfer ownership and control of museum collections and ultimately all knowledge and opinion to the Indigenous Peoples. Nonindigenous researchers and teachers are allowed to participate only on sufferance, since they lack the moral authority and the intuitive insight that comes from being indigenous. The demand for “Indigenous scholars” and “Indigenous scientists” is startlingly reminiscent of the “Aryan physics” and “socialist biology” of the 1930’s and 40’s, which further demonstrates the remarkable similarities among apparently disparate versions of collectivism.

The converse of the idealization of non-Western cultures is the depreciation, and frequently the demonization, of Western cultural achievements, whether expressed in art, literature, science, or abstract thought, and indeed the demotion of these achievements to the status of mere prejudices. The discipline of classics has recently come under fire for its supposed valuing of a tradition founded on racism and the unacknowledged theft of ideas from other cultures. Even to teach Latin or Greek is to perpetuate the sins of their ancient speakers. The Western tradition is even found guilty of “linear thinking,” as opposed to the intuitive, imaginative, and sympathetic thinking supposedly characteristic of non-Western peoples. The perfectly legitimate point that originality cannot be reduced to a formula and that our assumptions can never be made entirely explicit is made to imply something quite different, namely that articulate, systematic, and logical thought is somehow inferior to one’s undisciplined intuitions and that using the first to test the second is illegitimate.

To those who value the life of the mind, the most unfortunate aspect of the progress of collectivist thinking is that the validity of anyone’s assertions is held to lie not in their empirical basis, their logic, their testability, or their ability to explain a variety of phenomena of interest, but in their derivation from a category of persons whose intellectual and moral superiority is assumed. Jacques Barzun summarized this attitude as “the proof of the pudding is not in the eating, but in the cook’s pedigree.” This attitude, which was quite properly rejected in its older forms, has taken a new form that threatens all that we have gained since the seventeenth century in our understanding of human thought and behavior.

It may be too much to claim that the civil philosophy is a prerequisite or necessary condition to the objective study of human thought and action, but the correlation between the two is surely more than coincidental. The hierarchical philosophy held that its view of ultimate reality was necessary to sustain the social order, and that consequently any opinion about the human or nonhuman order that contradicted that view was to be suppressed. Even under these conditions, many aspects of the natural sciences were allowed to be pursued and some discussion of human affairs was permitted. Similarly for the collectivist philosophy, even in National Socialist Germany and Stalinist Russia, the natural sciences were often (not always) pursued in an objective manner, while the human sciences were bent to the demands of the regime’s ideology. It is unlikely that the objective study of human behavior bequeathed to us by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries can withstand the threat and allure of collectivist thinking. It is likely that some areas of investigation will persist at a high level of excellence, but one can hardly be optimistic about the fate of most teaching and research into the human sciences.

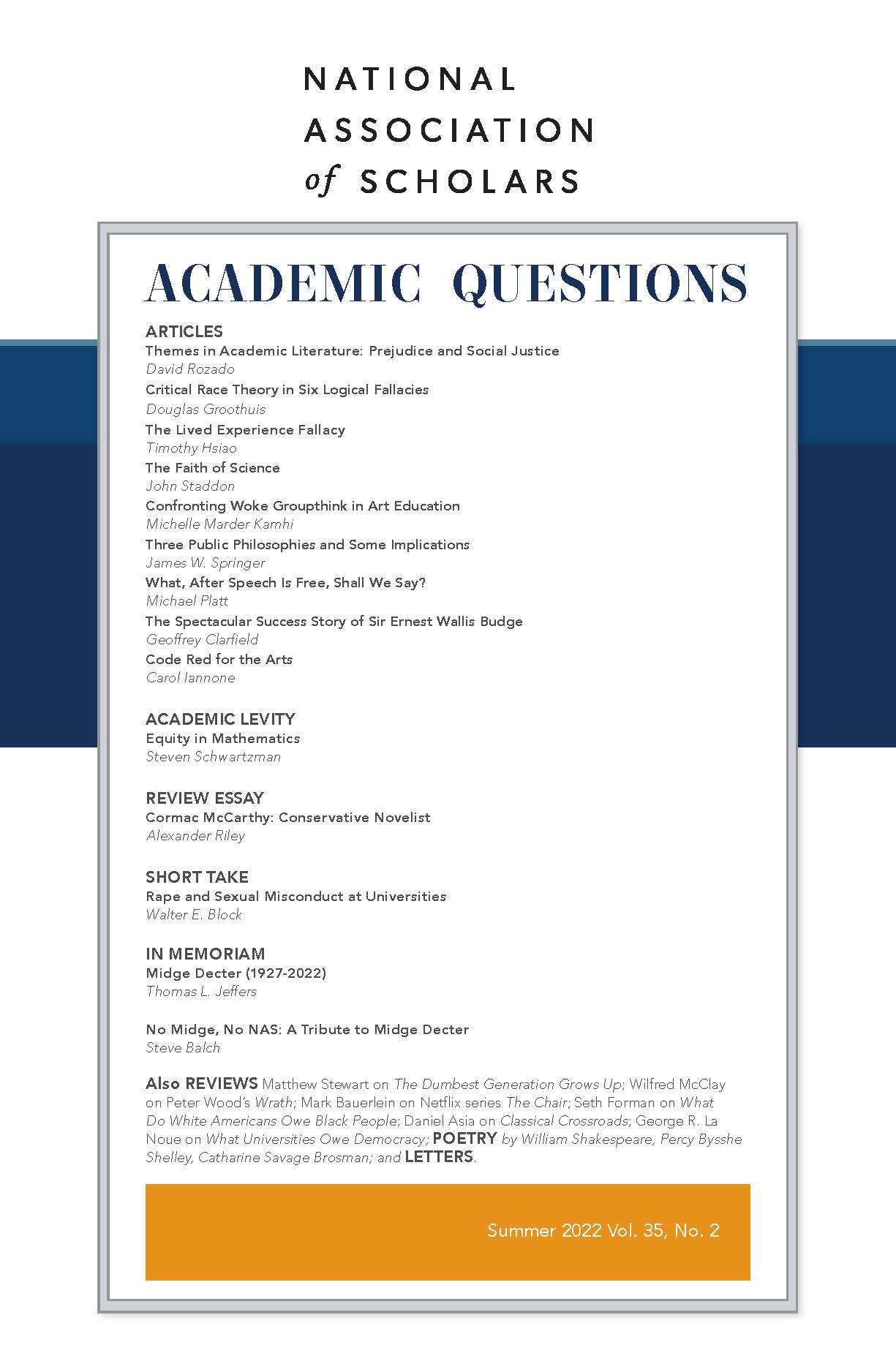

Image: Nils, Public Domain